Ten Ways to Get Sued - Harvard Negotiation Law Review

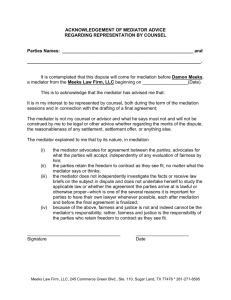

advertisement