Rains-retreat (VassÈvÈsa)

advertisement

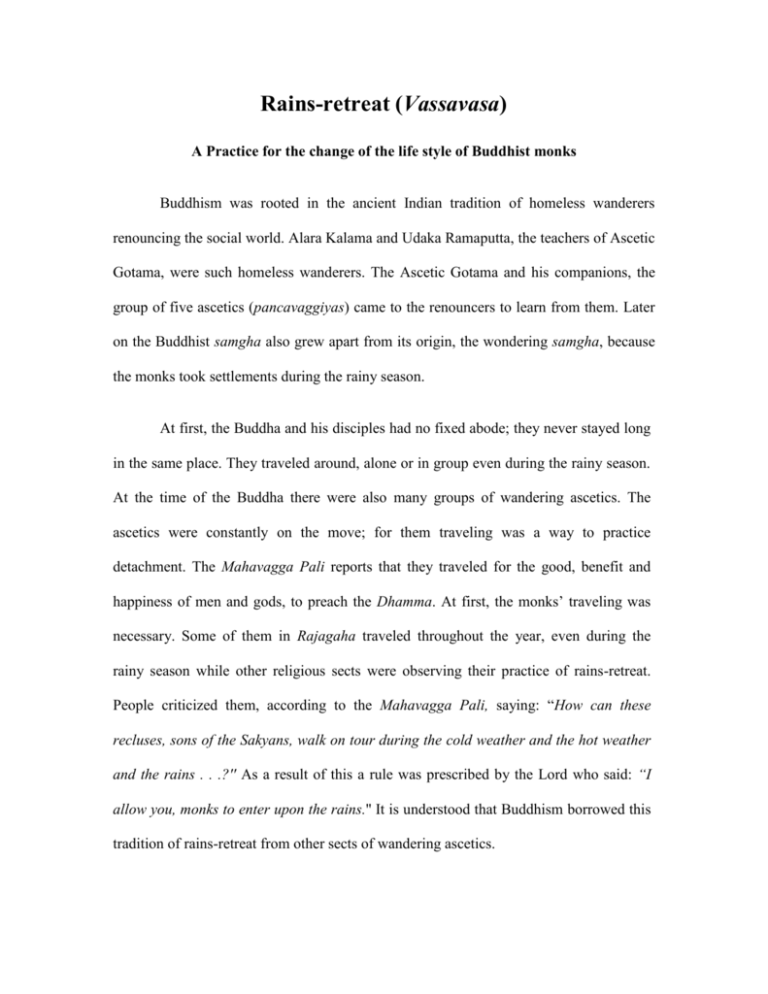

Rains-retreat (Vassavasa) A Practice for the change of the life style of Buddhist monks Buddhism was rooted in the ancient Indian tradition of homeless wanderers renouncing the social world. Alara Kalama and Udaka Ramaputta, the teachers of Ascetic Gotama, were such homeless wanderers. The Ascetic Gotama and his companions, the group of five ascetics (pancavaggiyas) came to the renouncers to learn from them. Later on the Buddhist samgha also grew apart from its origin, the wondering samgha, because the monks took settlements during the rainy season. At first, the Buddha and his disciples had no fixed abode; they never stayed long in the same place. They traveled around, alone or in group even during the rainy season. At the time of the Buddha there were also many groups of wandering ascetics. The ascetics were constantly on the move; for them traveling was a way to practice detachment. The Mahavagga Pali reports that they traveled for the good, benefit and happiness of men and gods, to preach the Dhamma. At first, the monks’ traveling was necessary. Some of them in Rajagaha traveled throughout the year, even during the rainy season while other religious sects were observing their practice of rains-retreat. People criticized them, according to the Mahavagga Pali, saying: “How can these recluses, sons of the Sakyans, walk on tour during the cold weather and the hot weather and the rains . . .?'' As a result of this a rule was prescribed by the Lord who said: “I allow you, monks to enter upon the rains.'' It is understood that Buddhism borrowed this tradition of rains-retreat from other sects of wandering ascetics. The rains-retreat, "staying during the rainy season or spending the rainy season, " vassavasa or vassa in Pali which required the monks to stay in a certain locality during the rainy season is of two kinds: (a) the earlier rains-retreat (purimikavassapanayika) that lasts for the first three months of the rainy season and (b) the later rains-retreat (pacchimikavassupanayika) that lasts for the last three months of the rainy season. One of the qualifications of a kathina worthy monk is to enter upon the earlier rains-retreat. In the Buddhist calendar, which practically follows the Indian tradition, rainy season lasts for four months namely in Pali Savana, Potthapada, Assayuja and Kattika. The first month of the rainy season generally falls on June or July. During the rains-retreat Buddhist monks are not to go on tour, but there are some exceptions. For example, monks may visit their parents if they are sick; they may visit another monk if he is sick or dissatisfied with his holy life or confused with dhamma etc. [See more example in the corresponding answer (A-0001, General Section). To read the answer, follow the link by giving a mouse click on the linked texts while pressing control key on your keyboard.] However his return must be made within seven days. Though it is said “seven days” monks may spend only six nights outside their monastery; because days are, in Vinaya, counted by dawns, and the first dawn of the day on which they start the journey is counted as one day. But during a rains-retreat monks may make several tours, again and again, for proper reasons for example when their parents are sick; but it is important to spend at least one night in their monastery between two journeys. If he does not observe the earlier rains-retreat, or he happens to have stayed away more than seven days during the rains-retreat, he is not allowed to receive the kathina robe, he cannot hold kathina ceremony, nor can he enjoy the kathina benefits which release him from practicing some vinaya rules. As to the places where the rains-retreat takes place, monks are specifically forbidden to observe the retreat in hollow trees, in forks of trees, in the open air, without lodging, in a charnel-house, under a sunshade, or in a water-jar. Over the centuries, monks' residence for the rainy season and for the other season has developed much. To dwell at the foot of trees was an original rule for primitive monks and“ a dwelling-place (vihara), a curved house (addhayoga), a long house (pasada), a mansion (hammiya) and a cave (guha) '' were, later, allowed as extra concessions. In the earlier development of the Order, monks were virtually homeless living on alms-food and wandering in all directions to spread the truth. Before monastic lodgings were permitted, they had to stay here and there: “in the forest, at the root of a tree, on a hillside, in a mountain cave, in a cemetery, in a forest glade, in the open air, on a heap of straw''. Then at the request of a rich man from Rajagaha the Buddha allowed lodgings for monks and lay devotees zealously participated in building and donating more dwelling places. However the condition of those dwelling places was actually simple being compared with later lodgings. Most of the lodgings were just for individual monks but not for group of monks. They have somewhat pitiable doors which were, indeed, pieces of flat wood tied with creepers and cords to the holes of the walls at the entrances. Next, windows were allowed, of three kinds: railing, lattice and stick windows. Next were draperies, shutters, and little bolsters across the windows. Next came the furniture: grass matting, solid bench, couch and chair, mattress, pillow, bed-cloth etc., came successively to be allowed, too. In a compass many buildings were made for different purposes: cells (parivena), porches (kotthaka), attendance halls (upatthanasala), fire halls (aggisala), huts for allowable things (kappiyakuti) privies (vaccakuti), halls in the places for pacing up and down (cankamanasala), halls at the wells (udapanasala), halls in the bathrooms (jantagharasala) and temporary sheds (mandapa). Over the years, supported by rich and royal families, lodgings for monks have developed into grand and great ones. Monks may build small monasteries (kuti) for themselves, but suitable sites for big or small monasteries must be approved by a group of monks according to the two training rules namely Kutikarasikkhapada and Mahallakaviharasikkhapada. Monks are united when a monk's monastery is constructed. That is their life style is now very much different from that of wanderers. Moreover, a monk dwelling in monastic community may act as an office bearer for monastic buildings: repairs-in-charge (navakammakaraka), assigner of lodgings (senasanapannhpaka), issuer of lodgings (senasanaggahaka) and storeroom keeper (bhandagarika). Monks may also appoint monastery attendants (aramika). The elder and elder monks are favorable in taking possession of the best seats and lodgings, and sells and lodgings are to be distributed according to seniority among the monks by an assigner monk. A monk may not accept two lodgings for a rains-retreat (vassavasa) and, on the other hand, without lodging monks may not spend their rains-retreat. The Buddha declared three periods for the assignment of lodgings: the earlier (purimaka), the later (pacchimaka) and the intervening (antaramuttaka). The earlier period for the assignment of lodgings starts from the day following the full moon of asalha, the first month of rainy season and it lasts for three months; the later period for the assignment of lodgings starts from the month following the full moon of asalha, and it also lasts for three months; the intervening period for the assignment of lodgings starts from the day following the Invitation Day (pavarana), with reference to the next rainsresidence, and it lasts for eight months. Monks may take hold of their dwelling places for all the three periods. That is they are allowed to dwell in monasteries all the year round, year after year. Introduction of the practice of rains-retreat did not bring about a complete settlement of the wandering monks; even after being given places to live, the Buddha and his disciples did not abandon traveling; particularly the Buddha himself did not yet settle in a certain place during the whole period of the first twenty years after attaining his enlightenment. But it is true that it served as a watershed which encouraged the monks to settle under shelters for the rainy season; it served as a bridge between two different periods in the history of the Buddhist monastic community: complete wandering and a settled life. When the rains-retreat is introduced to Buddhism, Buddhist monks started to settle under shelters. They had to stay in a certain locality at least for three months every year and they may continue their stay in a monastery year after year. By this, unity of the monks is encouraged. And by this their relationship with the lay community is also more supported than before. As a consequence, the Buddhist samgha developed much wider than its origin, the traditional wanderers' community. And life style of the Buddhist monks changed from that of homeless wanders to that of monastic men. With Metta, Ashin Acara