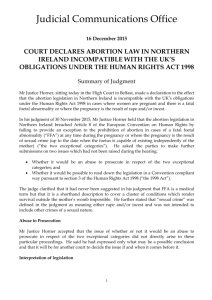

proceeding before the court - Corte Interamericana de Derechos

advertisement