MODERN ARABIC LITERATURE

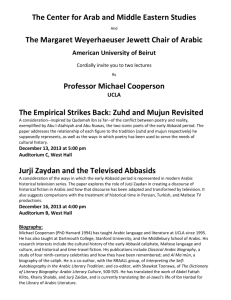

advertisement

MODERN ARABIC LITERATURE In 1798 French general Napoleon Bonaparte and his army invaded Egypt. This event heralded a new phase in Arabic literature. Western imperialism brought with it new genres: the novel and the short story. More important, the subsequent emergence of independent countries in the Middle East and North Africa meant that a multiplicity of viewpoints populated the Arabic literary scene. The literary scene began to come alive again in the 19th century, although many writers continued to employ older genres. Lebanon’s Nasif al-Yaziji, for example, composed maqamat in imitation of the medieval form. These maqamat served as a model for literary experiments by early 20th-century prose writers such as Muhammad al-Muwaylihi, Ahmad Shawqi, and Hafiz Ibrahim of Egypt. Shawqi and Ibrahim are also famous for their neoclassical odes. Arabic poets eventually cut loose from their classical moorings and looked to more modern forms, such as free verse—poetry with no fixed rhyme or meter. Iraqi female poet Nazik al-Mala'ika is most closely associated with the inception of the free-verse movement in the 1940s and 1950s. Modern Arabic poetry is a complex genre, including prose poems and forms that are experimental in varying degrees. Poets such as Salah Abd al-Sabbur of Egypt, Adonis of Syria, and Mahmud Darwish of Palestine have helped ensure that poetry remains an integral and living part of modern Arabic literature. The prose tradition as well underwent fundamental transformations in the modern period. Drama developed as a literary form in its own right, rather than a form derived from the maqama. The writer most often associated with contemporary Arabic theater is Tawfiq al-Hakim of Egypt. In his play Shahrazad (1934; translated 1981), he recast the famous frame story of The Thousand and One Nights. Autobiography also flourished anew in the 20th century. The genre received a major stimulus from the three-volume al-Ayyam (The Days) by Egyptian social reformer and intellectual, Taha Husayn. Published across four decades, from the 1920s to the 1960s, this passionate autobiography is a monument of modern Arabic prose and to the conquest of a handicap—the author’s blindness. Taha Husayn’s account details a dramatic life in both Europe and the Middle East. The autobiography is read by school children in countries from Sudan to Syria and has been the subject of television and motion-picture productions. The first Arabic novel is generally considered to be Zaynab (1913; Zainab, 1989), by Egyptian writer Muhammad Husayn Haykal. The novel, along with the short story, continued to grow in importance throughout the 20th century. Egypt’s Naguib Mahfouz, one of the best-known Arabic novelists of the 20th century, was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1988. His al-Thulathiyya (The Cairo Trilogy), which chronicles the travails of an Egyptian family, won him critical acclaim and, according to some, was the major contribution to his winning the Nobel Prize. The trilogy is composed of Bayna al-Qasrayn (1956; Palace Walk, 1990), Qasr al-Shawq (1956; Palace of Desire, 1991), and al-Sukkariyah (1957, Sugar Street, 1992). Yūsuf Idrīs of Egypt has been the acknowledged master of the Arabic short story, with his powerful narratives on sexuality and male-female roles. Palestinian writer Emile Habiby is best known for his novel al-Waqa'i' al-Ghariba fiIkhtifa' Sa'id Abi al-Nahs al-Mutasha'il (1974; The Secret Life of Saeed, the Ill-Fated Pessoptimist, 1982). He uses humor and irony to describe the plight of Palestinians living in Israel. Habiby is one of a group of Arabic writers who have moved away from realism as a literary mode. Many of them have drawn upon centuries-old literary traditions for material. A prominent example is the novel al-Zayni Barakat (1974; translated 1988), by Jamal al-Ghitani, which employs 15th- and 16th-century texts to create a postmodern narrative. The writer Yusuf al-Qa'id is another important figure. His three-volume Shakawa al-Misri al-Fasih (The Complaints of the Eloquent Egyptian, 1981-1985) demonstrates that the textual tradition a writer mines can hark back a few thousand years, to Egypt’s past under the pharaohs. Women living in many countries have become a strong presence in modern Arabic literature. Lebanese writer Hanan al-Shaykh’s powerful narratives about the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) include Hikayat Zahra (1980; The Story of Zahra, 1986). Palestinian Fadwa Tuqan is known for her poetry and autobiography, notably Rihla Sa'ba, Rihla Jabaliyya (1985; A Mountainous Journey: An Autobiography, 1990). Perhaps the most vocal and most prominent woman writer from the Arab world today is feminist physician Nawal El Saadawi, whose uncompromising and powerful prose has made her as many enemies as admirers. Her prison memoirs, Mudhakkirati fi Sijn al-Nisa' (1984; Memoirs from the Women's Prison, 1986), are in many ways a testimony to the interplay of politics and literature in modern Arabic letters. CONTEMPORARY ARABIC LITERATURE On the fast-changing contemporary scene, older literary figures such as Jamal alGhitani and Yusuf al-Qa'id remain major players. Such events as the migration of teachers and workers to oil-rich states on the Persian Gulf have given rise to more adventurous texts dealing with the plight of the intellectual in a type of exile. An eloquent example is the novel Barari al-Humma (1985; Prairies of Fever, 1993) by Palestinian writer Ibrahim Nasr Allah. Today, Arab writers who live in exile—because of political instability, repression, or other difficulties in their homeland—continue to write works in Arabic that circulate both in the Arab world and in Arabic-speaking communities outside the Middle East and North Africa. As renewed Islamic religious fervor spreads across the Arab world, Arabic literature has begun yet another process of adaptation. Religious-minded writers now compete with the more secular intellectuals in such genres as poetry, the novel, and the short story. At the same time, both religious and secular writers draw on much of the same premodern Arabic literary tradition. Novels by physician and born-again Muslim Mustafa Mahmud are best-sellers. The prison memoirs of female Muslim activist Zaynab al-Ghazali, Ayyam min hayati (Days from My Life, 1977), have had many printings. The vitality of the Arabic literary tradition becomes visible as one walks the streets of Middle Eastern and North African capitals and gazes in bookshop windows. At the same time, bookstores of London, Paris, and other world capitals with large Arab populations offer a similar experience. This diversity underscores the long and powerful history of Arabic literature and demonstrates its continued role in world culture.