Genre/Form: Introduction and its relationship to FRBR

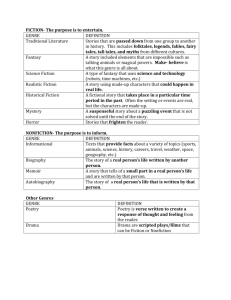

advertisement

Genre/Form: Introduction and its relationship to FRBR Robert L. Maxwell CCS Subject Access Committee American Library Association June 23, 2007 I’ve been asked to give some context to form/genre headings, including authority records. I’ll begin there, but I’d also like to place form/genre in the context of broader trends in cataloging, especially Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records and Functional Requirements for Authority Data. Let’s start with some definitions. [slide 3] What is a form/genre heading? One place to go is the MARC documentation (read through) This is an exceedingly confusing definition, one that makes little sense. The reason for this confusing definition is that in earlier versions of MARC there was a distinction (655/755), but it was realized that this was too thin a hair to split so they were combined. Main point: a genre/form term describes what the item is (655) vs. what is it about (650) Form /genre terms include terms such as: (see slide 4-5). These are all actual form terms in use in catalogs near you! Note that form terms may be combined with topical concepts or other sorts of qualifiers—“cricket” “American” “bagpipe” “vellum” “19th century”. Again, when used as a form term, each of these tells us what the resource is or contains, not what it’s about. All of these terms might be used in bibliographic records to lead users to form/genre aspects of the resources we have. For example, if a user wants to find bagpipe and continuo music, form-genre is the perfect way to lead him or her to it! But in order to make this useful, there are two things that need to be done. First, we need to present the terms to the users in a usable manner, i.e., in an index that distinguishes them from other words in the record. In order to do this we code these terms in a particular field, the 655 field and create an index that indexes the field. This is how we give access to our records through form/genre. [slide 6] If your library indexes form/genre separately, a very useful thing to do, your users can find, for example, Argentine short stories by doing a search on the term. Here’s how it works in the BYU catalog [slide 7-10] But this ONLY works of you have coded the term in 655. Unfortunately many catalogers continue to this day to code form terms in 650, a field reserved by MARC for topical terms, not form terms, and thus their libraries lose the ability to index by form. I said two things need to be done to make this useful. The first is indexing, made possible by proper coding. The second is controlling the vocabulary. This is done through authority control. There are two ways this could be done in the MARC environment. [SLIDE 11] One way would be to add a new fixed field code for “heading use.” We now have three of these: 008/14, indicating whether the authorized term in an authority record Maxwell — Genre/Form & FRBR — 2/13/2016 — 1 of 6 may be used for a main or added entry; 008/15, whether it can be used as a subject added entry; and 008/16, whether it can be used as a series added entry. As you know, a heading may be used for more than one of these. For example, most personal names can also be used as subjects, so their authority records are coded “a” in positions 14 and 15, but b in 16 since they aren’t appropriate as series headings. This coding prevents otherwise authorized terms from being used in bibliographic records in places where they don’t belong. Currently, topical subject terms, 650 in the bibliographic format, X50 in the authority format, are coded “a” in position 15 and “b” in 14 and 16. Now, all form terms are also topical terms. For example, if I have a book ABOUT Argentine short stories, it might be appropriate to use the term as a topical term, coded 650. If I have a book ABOUT Vellum bindings, it might be appropriate to use that term as a topical term in 650. It is possible to write ABOUT all form terms, so all form terms can potentially be used as subjects as well as forms. The reverse is not true. Not all subject terms can be used as forms. For example, the subject string “Psychology and literature” can only be used as a topic, not a form. So form terms are a subset of topical terms. If we were to add a fixed field value for “Heading use—genre/form added entry”, we could take existing subject authority records, and code them for whether their heading is appropriate or not for use as a form term. Position 18 is available! [slide 12] I am not aware that anyone has proposed this but it seems to me it might be a simple way to solve the problem of the creation of a set of authority records appropriate for genre/form terms. On the other hand, there are problems with this solution. One that immediately springs to mind is the problem that not all elements of subject authority records sit easily with form, particularly the references. [slide 13] For example, the term “literature” is a perfectly fine form term. However, its subject authority record (to the left of this slide), has the references you can see. Belles-lettres, Western literature, and World literature would sit perfectly well in an authority index for form terms because they are forms themselves. However, Philology, Authors, and Authorship, all perfectly appropriate broader terms for the topic Literature, do not work for the form since these are not broader forms than literature. So perhaps attempting to combine the records wouldn’t work, but I do think it would be worth looking into. The other approach is to create separate authority records just for genre/form. This is the approach LC appears to be taking, and it is the approach BYU has taken. Over a period of two or three years around 1998 we created authority records for every term in a 655 field in our bibliographic database, and have maintained complete authority control since. For terms that originated with LCSH, we did this by simply copying the SAR already in our catalog, and tweaking it a bit—[LOOK at GAR on slide 13], but usually no tweaking at all was needed [Slide 14] (except changing the X50’s in the SARs to X55’s and recoding the record as a genre record). Maze puzzles is an example of a SAR that needed little work to convert it to a GAR. We do not change any coding in the fixed fields and this procedure authorizes our database quite well. However, I would think that even with this approach it might be advisable to add a new fixed field value for genre/form heading use Maxwell — Genre/Form & FRBR — 2/13/2016 — 2 of 6 as suggested earlier (slide 12). Perhaps we will learn today if this has been proposed or planned? So, in order to allow our users to find resources using a form/genre approach, two things are necessary: consistent indexing, and controlled vocabulary within that index. Where do these controlled vocabularies come from? As with the 650 field, there are a number of thesauri that have been approved for use in the 655 field. One of the most important, of course, is LCSH, which includes a mix of form and topical terms as we have seen. But there are currently nearly 100 other thesauri that may be used. These are listed at the URL shown on the slide [slide 15-16] Why are there so many thesauri? Because lots of different communities see the value of controlled vocabularies to give access to form in their bibliographic records. But most are specialized. MESH creates form vocabularies for medical terms; the RBMS vocabularies include terms appropriate to rare book cataloging; AAT contains terms appropriate to giving access to art. LCSH is the most general of them all and perhaps the most familiar, but certainly not the only one, and I suspect most libraries that have form terms in their bibliographic records, like BYU, have a mix of terms from different thesauri appropriate to their needs. The existence of multiple thesauri causes problems, because their authors usually do not consult each other and so there are usually conflicts in terms or hierarchies. It can take a fair amount of massaging to make them all live together in the same sandbox of a library’s catalog, but it is doable. We’ve done it at BYU. I’d now like to turn to a discussion of how form terms fit into the FRBR model. [Slide 17] As you know, Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records is a relatively recent new model of the bibliographic universe from IFLA, based on the entityrelationship database model. [Slide 18] In this model a database contains distinct records for entities linked by “relationships.” [Read from the slide.] [Slide 19] In classical ER diagramming, entities are shown in boxes, relationships in diamonds, and attributes in ovals, linked by lines, and I will be using this diagramming in this talk (omitting the ovals for simplicity’s sake). I assume most of us are familiar with FRBR, so I will just briefly review the entities that have been defined in this model. [Slide 20] The Group 1 entities include “work”—a distinct intellectual or artistic creation. This seems clear to most people. “expression”—the realization of a work. This seems unclear to most people. “Realization” means “making real.” This means the creator takes the abstract work and puts it into a form—alpha-numeric text, music, choreographic notation, sound, images, etc. As long as the intellectual or artistic form of the work remains the same, this is one expression. If it changes (for example, if the talk I am giving today is translated into Japanese), that is another expression of the same work. “manifestation”—the physical embodiment of an expression. Once I’ve taken my work and made it an alpha-numeric text, for example a poem, I probably don’t want it just to stay that way in my mind, but I want to write it down on paper or in my computer. This is a manifestation of the expression. Then if I’m ambitious I Maxwell — Genre/Form & FRBR — 2/13/2016 — 3 of 6 want to get it published in a magazine. This is another manifestation of the same expression. If I become famous and my poem is later published in an anthology, this is yet another manifestation. “Item” is one copy from the set produced in the manifestation. These are called the “primary entities” and they have to do with works of human creation. The second group of FRBR entities are entities capable of creating group 1 entities. These are: [slide 21] A third group of entities has been defined, entities that can be the subjects of works. The group actually has a broader application than this, including form/genre, a concept distinct from subject as we have seen. These entities are: [slide 22]. Form/genre falls into two of these entities: Concept and Object. Most of the terms we’ve looked at thus far are concepts—remember the bassoon and continuo sonatas? But note that objects—defined in FRBR as “a material thing”—can also be used as forms in catalog record. For example, I cataloged a bullfighter’s cape once, complete with blood stain, that came with a collection of books about bullfighting. This cape, obviously, has a form, a cape, or in LCSH speak, a “cloak.” This is an object. I coded the term “cloaks” in a 655 field for this object, and doing a genre/form search on this term is the easiest way to find this object in our catalog, since it is not self-referential and so the entire description is cataloger supplied. Other instances of the object entity we’ve seen so far as form terms include “microfilms” and “compact discs”. Genre/form terms are a mix of FRBR concepts and FRBR objects. Many people think that genre/form applies to the work entity only, and indeed one of the attributes of work in FRBR is its form. However, as we shall see, many of these terms are more appropriate to other Group 1 entities. [Slide 23] An academic catalog is a work. If an academic catalog appears in more than one expression (for example, it is translated into another language), it remains an academic catalog. Similarly, an after-dinner speech is a work, and will remain an afterdinner speech even if it exists in multiple expressions (for example, the text and a recording of the speech). So the concept entity “after dinner speeches” is related to the FRBR work entity, not expression, manifestation or item. The same holds true for Arthurian romances, or Chinese poetry composed by San Francisco authors. A film adaptation, e.g. “Gone with the Wind,” will remain a film adaptation even if it goes through several expressions (perhaps the theatrical release and the director’s cut). Similarly, a scholarly periodical will remain a scholarly periodical even if it appears in multiple expressions and manifestations. In all of these cases, in an ER database the concept entity record would be linked to the work entity record. For example [slide 24] [Slide 25] Many form terms apply to the FRBR expression entity. Some of these include the following: Maxwell — Genre/Form & FRBR — 2/13/2016 — 4 of 6 Acrylic paintings. Under AACR2, an art work reproduced in the same medium remains the same work. Assuming “paint” to be the medium, an acrylic reproduction of an oil painting would remain the same work, but be a different expression of the work. So this form term would relate to the expression entity. Sea stories, American—Translations into German. A translation of a text into another language produces a new expression of the same work. This form string relates to the expression entity. Colorized films. Now I admit I cheated on this one. “Colorized films” does not yet exist in any thesaurus. But it seems to me it would be a perfectly good form term. A colorized film would remain the same work as the original, but would be a new expression, so the relationship link would happen at the expression level. Bilingual books. A bilingual book contains an original text with a translation. As already seen, translation creates a new expression. Condensed books. In AACR2, if abridgement does not involve rewriting, the abridgement remains the same work as the original. However, since the intellectual content has changed, a condensed book would be a new expression of the original, and the link to this term in an ER database would be at the expression level. Films for the hearing impaired. I link this at the expression level because I assume the addition of something like closed captioning to a film would not create a new work, but a new expression of the work. [Slide 26] Here is an example of how this might work in an ER database. Note that each of these entities could be linked with relationship links to many other entities. For example, the person entity Herman Melville would be linked with a creator link to all the works he created represented in the database. [Slide 27] There are many genre/form terms related to the entity manifestation. Many have to do with the physical characteristics of the manifestation, such as Compact discs and audiocassettes. The same expression of a work can be recorded on different media. These make different manifestations, not different expressions, so the form term would be recorded as a link to the manifestation record. Daguerrotypes, etc. The same photograph can be reproduced using different photographic media. These remain the same expression of the original work, but are different manifestations. A digitized version of a print book is a new manifestation of the original expression, so the form term “electronic books” would be linked to the manifestation record. Maxwell — Genre/Form & FRBR — 2/13/2016 — 5 of 6 “Out of print books” is not a form term related to the physical characteristics of the resource, but rather to its availability. Since manifestations go out of print, not expressions, if this form term were applied to a resource, it would be applied at the manifestation level. [Slide 28] Here is an example of how this might work in an ER database. Notice the form is linked to the manifestation record. [Slide 29] Some form terms even apply at the item level, though they are rare. Here are a few. Autographs is a form term that may be used if a resource contains an autograph. This would always apply only at the item (copy) level. Binding terms apply at the item level if the bindings are unique. These terms are frequently used in rare materials cataloging. These include terms for the binding itself (“blind tooled bindings”), the paper that may have been used in the binding (“batik papers”) and various techniques used to decorate the book or the binding (“marbled edges.”) Cancel leaves is another rare materials form term that would probably apply at the item level. When a leaf in an early printed book was discovered to have an error it was sometimes replaced by a corrected leaf. Frequently when this occurred only some of the copies of a manifestation were corrected—sometimes only one copy! The form term “cancel leaves” would therefore probably be used at the item level. [Slide 30] This is how this might look in an ER database. Why is this important? Which FRBR entity a particular genre/form term applies to is of little importance in the MARC environment, where every piece of the last slide would be coded in a single record, and how the genre/form term applies is not specified. But it will matter as we begin to create ER databases on the FRBR model. I have demonstrated that genre/form terms, all currently coded in the same way, will actually have relationships to different entities in a FRBR based database. Both for future database construction, and for purposes of any hope we may have of splitting MARC records out into FRBR ER records, some sort of mapping needs to be done. One of the many tasks that will be needed to lead us to the promise of FRBR will be to examine and study all form terms and make guidelines for appropriate FRBR entity links. Maxwell — Genre/Form & FRBR — 2/13/2016 — 6 of 6