2.1 Flatland - Microsoft Research

advertisement

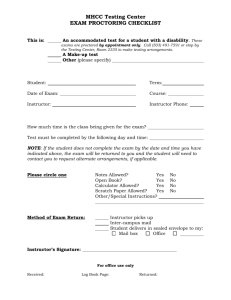

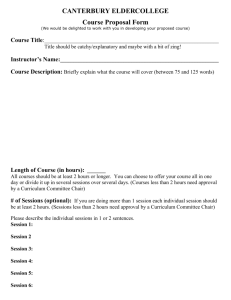

A Software System for Education at a Distance: Case Study Results Stephen A. White, Anoop Gupta, Jonathan Grudin, Harry Chesley, Gregory Kimberly, and Elizabeth Sanocki November 11, 1998 MSR-TR-98-61 Microsoft Research Redmond, WA. 98052 USA A Software System for Education at a Distance: Case Study Results Stephen A. White, Anoop Gupta, Jonathan Grudin, Harry Chesley, Gregory Kimberly, and Elizabeth Sanocki Microsoft Research Redmond, WA. 98052 USA ABSTRACT Computers and networks are increasingly able to support distributed, real-time audio and video presentations. We describe Flatland, a highly flexible, extensible system that provides instructors and students a wide range of interaction capabilities. Prior research focused on the use of such systems for single presentations. We studied the use of Flatland over multi-session training courses. We found that even with prior coaching on the use of the software, instructors and students require experience to understand and exploit the features. Effective design and use will require understanding the evolution of personal and social conventions for these new technologies. Keywords Distance learning, multimedia presentations. 1 INTRODUCTION Computers and networks are increasingly able to support distributed, real-time multimedia presentations, including live audio and video. Distance education is controversial when seen as a replacement for standard classrooms, but can provide advantages when classroom attendance is not possible or when a student would like to participate more casually. Not everyone who could benefit from internal training and other organizational learning activities can participate in person. At times, we might be interested in seeing a presentation from our office, where we can timeshare with other activities or easily disengage. How distance learning technologies will be received and used by instructors and students is a significant research question. Isaacs and her colleagues at Sun Microsystems conducted experiments with Forum, a live multimedia presentation system [1, 2, 3]. They contrasted live presentations with Forum presentations and reported mixed results. Audience members appreciated the convenience of attending on their desktop computers, but felt it was less effective than live attendance, as did the instructors. Instructors found the lack of feedback disconcerting, and sometimes could tell students were paying less attention. The Forum experiments focused on single-session presentations. Most technologies experience a learning curve. It takes time for individuals to develop an awareness of the range of features and how they can be used. It takes even more time for social conventions to develop around the use of technologies that support communication and coordination: Books on ”email etiquette” are now being published. Such conventions can vary across groups. For example, who speaks first when a telephone is answered differs in different cultures. Such conventions must be established and agreed upon, and then learned. To be used effectively, interaction-oriented applications that support distance learning will require the development of conventions. Some conventions may be useful across settings, others will depend on an instructor’s style or class composition. Different conventions may work equally well, but one set will have to be adopted by each class. This will take time, because distance learning technologies involve a complex set of features to compensate for the loss of faceto-face contact. It will also take time because most learning of conventions is done tacitly, with little conscious attention or reading of written behavior guides. Therefore, the previous research with live multimedia presentation systems, focusing on first-time use, represents only the first step. This study builds on the previous work by looking at the use of distance learning technologies over multiple sessions, to understand how experience can evolve with exposure, and what some effects of direct intervention might be. Users will find ways of exploiting the technology that are not anticipated by its designers, but designers must do what they can to understand and anticipate use. These technologies must be usable the first time and as users climb the learning curve. Training cannot be only feature by feature explanation, it must illuminate the pitfalls that are likely en route to more sophisticated use. To explore these issues and provide guidance for design, we developed a flexible tool for distributed multimedia presentations and observed its use in multi-session classes. After presenting the system, we outline the interaction needs and the features available to support them. The most effective use of these interaction channels is not always obvious. Even with training, a class will find its own way. In the case studies that follow, we assess how the system was used and how use changed over time. We occasionally intervened to suggest the use of features, then observed which features continued to be used and which did not. Through such studies we can start to identify effective conventions that can be supported or promoted, and less effective practices that might be avoided. We can determine features to be dropped, added, or redesigned, as well as what to emphasize in training. 2 SYSTEM In this section we discuss the architecture and features of the system used in the study. The system consists of two applications, Flatland and NetMeeting. Flatland is a flexible synchronous education environment designed for tele- presentation. NetMeeting is a synchronous collaboration tool that supports application sharing. 2.1 Flatland Flatland combines NetShow streaming audio and video with a collection of audience feedback mechanisms that allow the presenter to receive both solicited and unsolicited responses from the viewers. Figure 1 shows the main Flatland screen layout, as seen by a presenter. Figure 2 – Flatland System Figure 1 – Flatland Presenter Layout Figure 2 shows the Flatland components and their relationships. A presenter communicates with a number of audience members using NetShow video and Flatland. The audience, in turn, can pass questions, answers, and requests back to the presenter via Flatland. 2.1.1 User Interface Figure 1 shows the main Flatland window layout, as seen by the presenter. The audience sees a similar view, but without many of the controls and buttons. The middle left section of the layout contains the video of the presenter, provided using Microsoft NetShow 3.0 [7]. Any Flatland participant with a video feed could present, but in these studies only the instructor did. The upper right section of the window contains slides and questions, as defined by the presenter. This area can include slides generated by Microsoft PowerPoint, simple text slides, and audience Q&A slides that allow the audience to vote by selecting one of the answers to a multiple choice question. The presenter can also use a ”pointer” to indicate specific sections of the slide during the presentation. The presenter controls the selection of the currently displayed slide. A History button above the slide area, however, generates a separate window with the entire set of slides for the current presentation. This allows any viewer to browse the slides not currently being displayed in the main window. Presenter controls in the slide area include facilities to select the slide to be displayed, using either the ”next” and ”previous” arrow buttons on the top right or the table-ofcontents pop-up on the top left. There are buttons to edit or delete the current slide. A presenter can also create a new slide on the fly and insert it in the presentation. Below the slides, on the right, is a text chat area. This allows free-form communication between audience members or between the audience and the presenter. Interactive chat gives audience members a strong feeling of the presence of other participants, and can be invaluable for resolving last minute technical problems that audience members may encounter. This window also reports when people join or leave a session. Although free-form chat is valuable in providing an open and unrestricted communications channel, it can easily become overwhelming. For questions specifically directed at the presenter, a separate question queue is provided to the bottom left of the window. In this area (hereafter called the Q&A window), audience members can pose questions for the presenter. They can also add their support to questions posed by others by incrementing a counter. This voting capability could reduce duplicate questions and help a presenter decide which question to address next. Finally, the upper left area of the window provides several lighter weight feedback mechanisms. On the right are two checkboxes that allow the audience to give continuous feedback on the speed and clarity of the presentation, displayed as a meter on the presenter window. On the left are buttons to leave the presentation, to show a list of audience members, and to raise a hand for impromptu audience polling. A pop-up, floating ”tool tip” shows a list of members with their hands raised if the cursor is left over the hand icon. The same information is also displayed in the pop-up audience member list. 2.1.2 Implementation Flatland is built on top of three major components: Internet Explorer (with DHTML & JScript), NetShow, and the Microsoft Research V-Worlds core platform. Figure 2 shows the relationships between these components. All user interface components of Flatland are implemented in DHTML. DHTML provides a number of pre-built user interface components, and allows for rapid prototyping of layouts. Used together with JScript, it allows for fast development and easy web-based deployment. NetShow provides the streaming audio and video components of Flatland[7]. It is displayed and controlled in the Flatland system using an ActiveX control. The V-Worlds core platform was developed by the Virtual Worlds Group within Microsoft Research[5]. It provides a distributed, persistent object system that transparently handles client-server-client communication and object persistence between sessions. The V-Worlds platform is used in other Microsoft Research projects as the basis for a 3D immersive virtual world. Flatland uses a model/view/controller architecture [6]. The model contains the raw data of the application. The view and controller provide the user interface. The Flatland model is implemented as a set of distributed objects within the V-Worlds client-server-client platform. This allows the same objects to exist on the server and all of the connected clients simultaneously, and to automatically communicate changes to the objects among all of these locations. For every element of a presentation – slide, Q&A item, question queue, etc. – there is a distributed model object within the V-Worlds platform. The Flatland view/controller is implemented in DHTML/JScript, using scriptlets [8]. A scriptlet is similar to an HTML frame, but also includes the ability to export implementer-selected properties and methods for encapsulated external access. A Flatland screen layout includes a separate scriptlet for each element of the presentation. When the scriptlet is initialized, it accesses properties and methods of the model to determine what should be displayed to the user. When the user subsequently interacts with the scriptlet DHTML and changes something, the scriptlet calls a server method of the model object that updates the current state of the object as appropriate. These changes are automatically propagated to all the clients. Each of the individual scriptlets on the clients then updates their displays to match the new state. By separating the model within the V-World platform from the view/controller within Internet Explorer’s DHTML framework, we achieve two primary goals. First, the same model can be displayed in different ways simply by switching the scriptlet that renders it. Second, the separation compartmentalizes the different aspects of the architecture. This is especially useful in the case of the distributed model, since distributed simultaneous operation can be difficult to understand and even more difficult to debug. Flatland uses two separate channels to communicate with the audience – the Netshow audio/video stream, and the VWorlds distributed object system. Due to buffering considerations in the video stream, the latencies of these two channel are significantly different – a fraction of a second for the V-Worlds system, and several seconds for NetShow. To compensate for this difference, Flatland dynamically measures the video delay and queues certain presenter events – slide changes, pointer activity, etc. – for delayed playback in sync with the video. The Flatland implementation architecture has proven effective for rapid prototyping, allowing us to change designs and try out different options quickly and with minimal staff. At the same time, its performance characteristics are sufficient for deployment and use in realworld, working contexts. 2.2 NetMeeting We learned that demos are a critical component, not supported by Flatland, of frequently-offered classroom training courses. We addressed this with the application sharing feature of NetMeeting, a freely available software application. Instructor and students ran Flatland and NetMeeting sessions concurrently, first logging into Flatland and then joining a NetMeeting meeting. NetMeeting application sharing allows everyone in a NetMeeting meeting to view any application running on a participant’s machine. Viewers see dynamic screen changes and mouse pointer movement (with less delay than in Flatland). NetMeeting also supports point-to-point audio and shared floor control, but these were not used. 3 INSTRUCTOR-STUDENT INTERACTION At the heart of Flatland are the awareness and communication that link instructor and students. Thirty years of experiments with synchronous meeting support systems support maintaining several interaction channels. Design decisions addressing display arrangement and human-computer dialogues must be considered in parallel with these features. In standard classroom instruction, the physical environment is visible and shared. A full and flexible range of communication channels is available – visual observation, voice, expression, gesture, passing notes, writing on a board, throwing an object for emphasis, even walking over to view student work. Nevertheless, effective teaching is a demanding task. Despite years of having been a student, teachers need training. Courses to improve presentation skills are standard fare in large corporations. Systems that support distributed meetings or distance education force all awareness and communication to be mediated digitally. Users must find ways to compensate for lost information and develop social conventions and protocols to replace those disrupted by technology. Past research can provide some guidance in using these channels, but it is not clear how to use them together effectively, and what content is best viewed through which channel. 3.1 Interaction requirements The following categories of communication and awareness: 3.2 information involve Lecture video and audio, possibly including gestures Slides, with a pointer Student questions on lecture content, including ability to support another's question Technology-related questions or problems Process-related issues, such as whether the student is understanding the material (in a class, this can be communicated publicly with a comment or privately with a facial expression) Discussions among students Knowledge of participants, including arrivals and departures Spontaneous polling of students by instructor Sharing of applications for demos or labs Spontaneous writing and drawing (as on a blackboard) Interaction channels Interaction channels available to participants in the studies: Synchronized audio/video window carrying the lecture Gesturing within range of the camera Slide window with pointer capability Text slides created on the spot (tools provided) Q&A window with question prioritizing capability Discussion or chat window with machine-generated announcements of participants coming and going Attendance window Slow/fast and confusing/clear checkbox features Hand-raising feature Interactive query slide creation (tools provided) NetMeeting application sharing NetMeeting multi-user whiteboard NetMeeting chat window Telephone Discussion among students by visits during a class or by various means between classes 3.3 Interaction issues Some interaction channels are clearly matched to specific interaction requirements, such as the video and slide windows. In other cases, the appropriate channel is ambiguous, could remain undiscovered or unused, or could be interpreted differently by lecturer and students, potential sources of miscommunication and confusion. For example, consider student questions related to lecture content. The Flatland Q&A window is designed to handle them, but students may use the chat window instead. Chat is familiar and this window is active early in a class, reporting arrivals and technical start-up discussion. Conversely, if Q&A window use is established and less attention is paid to the chat window, should the Q&A window be used for technology issues? NetMeeting adds another option with a second chat window, one that permits private exchanges. Attendance can be monitored over time in the chat window, by bringing up the attendance window, by asking for a show of hands, or by using an interactive slide. Which are used? How important is anonymity -- for questions, voting, hand raising, or responses to interactive slides? Non-use or confusion can potentially result from asymmetry in lecturer and student experience, from one side's ignorance about the other's experience. Flatland participants arrive with behaviors and conventions formed in different environments. How easily will students adapt to a classe where smiling at the instructor is not possible but telephoning is? This partial list of interaction issues in Flatland-supported classes suggests the complexity of the environment. Learning effective use may well take time and require the establishment and evolution of conventions. Along the way, we will discover how to design better interaction channels. Each redesign will require another effort to work out effective approaches to communicating. 4 METHOD Two classroom courses in a corporate environment were taught desktop to desktop, with no live audience. We made no alterations to the course scheduling, materials or structure. We simply had the instructors deliver the courses through our system. The two courses were “Introduction to HTML” and “C Programming 1”. The HTML course is two three-hour sessions. The course includes integrated labs. The C Programming course is four 2-hour sessions. It is primarily a lecture style course with take-home labs. Both courses include live demonstrations given by the instructor. The students were volunteers from a list of students waiting to attend the next offering of the classroom-based course. Four students volunteered for the HTML class and 10 for the C Programming class. The students have a variety of job functions and technical expertise, but all have substantial computer experience. Although this population is thus not general, it may be representative of early adopters of technologies of this kind. More important, these students could take in stride some of the technical difficulties and human-computer interface deficiencies that inevitably accompany the first use of a system. Each instructor was situated in a usability lab observation room, enabling us to videotape, log usage, observe, and take notes unobtrusively. One student in each class also participated in a (different) lab. The other students worked from their offices. Prior to the first class, the instructor received a brief demonstration of Flatland and NetMeeting. We also worked with the students to insure they had the software installed. Throughout each session we had at least one observer and one person available for technical support. Following each session we asked instructor and students to fill out questionnaires (usually on-line), and one or more of us verbally debriefed the instructors to obtain more detailed explanations of observed behavior. In discussions with the instructors, we asked them about features that were and were not used. We asked them how they thought each on-screen control worked and explained those that the instructors found confusing. For example, we explained that the mouse pointer was only visible to students when a button was depressed. We demonstrated the preparation of a sample interactive slide. Thus, we did not always leave them to explore by trial and error, but as noted below, our suggestions were often not picked up. The instructors are professional teachers with personal styles, confident in their control of the class and material. For the fourth lecture of the second class, we intervened more directly to see the effect of trying to dictate a protocol. Students were asked to use the NetMeeting chat channel for technical questions, the Q&A feature for content questions, and the Flatland chat for discussion. The instructor was pressed to prepare and use interactive slides, and asked to request feedback on the clarity and speed of the class by having the students use the check box interface. These interventions had some effect on behavior, although the channels were not used strictly as suggested and the instructor did not warm to interactive slides. 5 RESULTS Based on our observations, logs, and participant reports, Flatland use changed considerably with experience. Some change was incidental to the study — learning to identify and recover from unforeseen technical problems. Some resulted from better understanding of the interface and features. As people grew comfortable with key features, they were able to experiment with or try additional features. These are familiar aspects of adapting to any new system. We also observed shifts in how instructors and students used different interaction channels. After a brief overview of Flatland use, this section focuses on changes over time in classroom behavior. Some of the change involves overcoming misperceptions based on prior experience. Some new behaviors succeeded and were retained, while others were abandoned. In some cases, apparently desirable changes in behavior were not established, even when pointed out. Understanding these phenomena is important in improving the design and training for these technologies. What drives these changes? We identified two major factors. One is the ambiguity about which channel to use for particular information. The second is uncertainty or incorrect assumptions by the instructor about the student experience, and vice versa. This failure to appreciate the other side’s experience, also reported by Isaacs and her colleagues, was widespread. Some is due to lack of full understanding of features, even after they are explained or demonstrated. Some is due to different equipment configurations. Some is due to the lack of the normal visual and auditory feedback channels classes are accustomed to relying on in classrooms. These are explored below. 5.1 Distance Learning With Flatland and NetMeeting Overall, the experience reflected many of the Forum findings of Isaacs et al. [1,2], which were encouraging but mixed. Issues included basic video interface issues. The camera field of view could not include natural hand gestures and still give the students a feel of being close to the instructor. The instructors, despite being aware that eye contact was an issue, did not frequently look at the camera. Not surprisingly, instructors report less awareness of the students and the student experience, not knowing who was attending or what they were thinking. This is more serious in a class than in the informational presentations examined by Isaacs and her colleagues, because of the implicit contract between instructor and students to participate (students sign up for a class). For example, following a class break, instructors want to know that students have returned and are ready to continue. Although Forum presenters could and did ask Yes/No questions in part to gauge audience attention, instructors are likely to ask people directly to signal their presence. Lack of response (or perceived lack of response if the response is missed, discussed below) is then more unsettling. As discussed in the next section, the instructors’ comfort level changed over time. However, it remained an issue. After his second (final) class, Instructor 1 wrote: ”Very little feedback from students… For some reason they seemed reluctant to give comments or participate. This should be explored as the teacher needs some kind of feedback…” He wrote about NetMeeting: ”This worked very well from my end but would be very interested how it worked for the students.” Asked whether he would recommend Flatland or classroom participation, he wrote ”I still think in person is best. If logistics do not allow in person then this is the next best thing.” (He was comparing Flatland favorably to large-room video teleconference instruction with PowerPoint.) The second instructor made similar comments after the first two classes. Although his answers shifted in the third and fourth lectures (see below), he concluded ”In a conventional classroom I have lots of visual cues as to attention level and comprehension that are missing here. For instance, if I say something and get puzzled looks, I repeat myself using a different analogy or different words or a different approach. Not so easy to do that here.” His final assessment was mixed: ”I don’t believe all courses would be equally adaptable to Flatland. Also, what makes many trainers good trainers is the classroom itself. We are performers, stage actors if you will, not radio voices.” With this insight he was observing that there is a new skill to be learned. Nevertheless, many Flatland features are designed to provide feedback missing to “radio voices.” And although we felt there may have been too many such channels to choose among, this instructor wrote that he would like to see ”more or different or better ways to do open ended questions.” Students, on the other hand, made use of the ability to timeshare and do other work while attending. Even in the observation lab, with fewer personal materials and distractions at hand, a student methodically checked email and carried out other tasks during slow periods, seeming to use verbal cues from the instructor to know when to return to the class. (When asked how he knew to return, he said ”I’m not sure, I just did.”) Despite this, they rated their overall level of ”attention to class” consistently between 75% to 85%. This is closer to the level Isaacs and her colleagues found among live attendees (84% vs. 65% for Forum attendees). This may reflect that the focus of students registering for a class is stronger than remote attendees of an informational lecture. The fact that students might particularly appreciate Flatland, as reported for Forum, was sensed by Instructor 2, who wrote ”That students wanted to take the follow-up course in a similar manner was evidence that they thought the course and the presentation technique were good.” 5.2 Changes in Interaction Behavior and Perceptions over Sessions ”Before it was just a feature. This time it was a tool.” —Instructor 1, discussing ‘hand raising’ after the 2nd class In a classroom, instructors use a set of tools to express concepts and ideas. Over time they develop a personal approach to using the tools, a presentation style. When instructors start presenting in a new teaching environment, they will need to adapt their presentation styles to the new tools available. In this section, we explore changes in behavior by both the instructors and the students as they learn to use the system, to interact through the system, and gain a sense of presence with each other. (Each person had had about 15 minutes of individual instruction in the use of the system features, but no prior interactive experience.) 5.2.1 Presenting Many of the instructor’s behavioral changes over time could only be identified by observation, because the instructor himself appeared unaware of the change when questioned about it immediately after a session. However, the post-class questionnaires provided some evidence. The questionnaire had several measures for which instructors were asked to present ratings on a scale of 1 to 5 (5 being high or good). Although most responses were relatively static across classes, three questions revealed a shift of 2 points or more (all with Instructor 2). The strongest shift occurred in response to ”To what extent did you get a sense of the students’ attitudes about the class.” In the first class, he skipped the question. When asked directly he said ”I have no idea,” that he typically relies on audience feedback and was used to seeing the student. (He remarked, though, that ”I like to talk” and thus was not overly bothered.) After the second class he rated this ‘1,’ meaning he had the weakest possible sense of student attitudes. After the third class, however, he rated it ‘3’ and after the final class ‘5,’ the highest possible rating. In response to ”How well do you think you handled student questions?” his ratings were 3, 4, 4, 5 over the four classes. ”To what extent did Flatland interfere or detract from the class?” received no response the first class, a written comment ”too early to say” after the second, a ‘4’ (quite strong interference) after the third, and a ‘2’ (quite weak interference) after the fourth class. In an overall assessment, he wrote ”Much more comfortable with the Flatland environment after 4 sessions.” The first instructor, who taught only two classes, showed no large shifts in the questionnaire, but remarked in discussion after the second class that he ”felt more comfortable… was not as distracted by his own image.” The instructor’s window shows the video image that is being seen by the students, delayed by several seconds. Although the students hear audio with the same delay, the instructor of course does not get the audio, and thus experiences the video out of synch. Following the first class, this instructor recommended dropping the ”distracting” instructor video feedback feature, but in the second class had learned to use it to check his own camera image and ignore it the rest of the time, and now favored retaining the feature. Some changes involved unlearning familiar behaviors. For example, the first instructor initially paused after every slide transition. When asked why, he mentioned that in his experience with VTC he used the video to see when the slide changed for remote students, thereby compensating for delays. In Flatland the instructor sees slide changes immediately but sees the AV delayed by an average of 12 seconds. This instructor assumed that he needed to compensate. Reminded that the students see everything in synch, he stopped compensating. Ironically, when using NetMeeting, where the display was not delayed and thus out of synch with Flatland audio, he did not relearn to compensate despite being reminded. Generally, instructors began stiffly as they learned to deal with the camera and mouse control of slides, and inform the audience of transitions that were obvious. One instructor said ”I spent most of my time making sure that I was in the center of the camera.” By the end of the second session both instructors were comfortable enough with the video and slide advance to make smooth slide transitions and use the pointer to direct attention to items in the current slide. Pointer usage increased over time. From 9 to 12 times for Instructor 1, who said “ I started using it as soon as I was aware of it” when asked how long it had taken to get familiar with the pointer. The second instructor used the pointer 0, 26, 34, and 36 times. Responsiveness to multiple input channels built over time. In his second session, Instructor 2 wanted to respond to a question with an example. He was in NetMeeting for a demonstration and edited text there for this purpose. In his third class he began to make heavy use of dynamically created Flatland text slides to type in code examples and strongly endorsed this as a whiteboard substitute. It was also only in the third class that he responded promptly to Q&A window queries, and in the fourth that he monitored the chat traffic reliably. As instructors’ comfort levels rose, they added characteristics of personal style. For example, Instructor 2 started greeting students in session 3, and at the end recommended more and clearer identification of students by name in the interface, a suggestion he did not make earlier. 5.2.2 Attending ”But I wouldn’t have gotten this level of interactivity, and I think we used the remaining time more effectively than if we had been there in person.” —A student comparing traditional classroom to Flatland Now we consider the students’ experiences — the channels used, the category of interaction (class related, social, technical and user interface), and the interacting parties (instructor, student and technical support). In the first session of the second class, the instructor and the students focused on dealing with technical startup problems and learning the interface. Technical discussion comprised over 80% of the chat discussion and only one content question was asked. Two students were discouraged enough to drop the class. Subsequently the number of exchanges doubled with three times as many questions being asked in the second class. In the final two classes, the overall rate of exchanges stayed relatively constant, but content discussion increased as technical Flatland discussion dropped. Over the last three sessions, exchanges changed from 27% class-related and 11% social to 60% class-related and 26% social. Communication directed to the instructor doubled, with the number of response to the instructor’s comments and questions rising from one in session 2 to 24 in session 4. This marked increase in response is mostly due to the instructor asking students questions through the audio/visual channel. For example, Instructor 2 would show some code and ask students to identify the errors. The students were quick to notice the improvement in interaction. When asked their impression of the Flatland experience and how well Instructor 2 presented, typical comments were ”Some difficulties with the interaction between new technology, students, and teachers” (session 1), ”the interaction with the instructor was easier…his interaction was improved, and the course was likewise improved” (session 2). The last session ”had the best interaction” but ”still left room for improvement.” Among the contributing factors are increase in familiarity with the technology, a reduction in technical problems, and improved technical support. and the increase in exchanges between instructor and students. Asked how distracting Flatland was, student ratings fell from 2.8 to 1.7. 5.3 Challenges to effective interaction That learning takes place is not surprising. Even better is to identify specific aspects of behavior that are useful or not useful, and how they are acquired. This can improve designs and help new users avoid as much trial and error. Most useful of all is to identify learning patterns. What challenges do classes face with distance learning technologies? Understanding these can inspire further improvements and enable us to anticipate possible problems in new designs. In the next two sections, we identify two patterns abstracted from these studies. 5.3.1 Uncertainty about appropriate interaction channels ”Once the instructor had answered it (a question), I didn't like the feeling of not being able to say ‘Thank you.’” —A student responding about the Q&A window feature A lot of interaction channels are available, but not necessarily too many for the complex task of communicating contextual and course-related information. The instructors requested additional channels, notably point to point audio. Researchers have proposed yet others, such as emotion meters [4] and applause meters [1]. In Section 3.1 we noted that normal classroom settings involve many communication demands. We are so familiar with them that we often handle them without conscious awareness. Thus, we can probably handle many channels, but have to discover which are effective, and most importantly, all participants must agree, so that they monitor and interpret information appropriately. For example, the Q&A window was provided for students to enter and vote on questions. One student reported after his first class that he assumed this window was for the instructor to pose questions. Active student use of the less formal looking chat window created this misperception. Virtually no use of Q&A was made in this class, suggesting a shared misperception. Consider the ‘raised hand’ icon and counter. The instructors saw it as we intended, a mechanism for students to respond to their queries. Some students saw it as a means to ”raise their hand” to be called upon, and tried it, only to go unnoticed by the instructor. When the first instructor wanted to know whether the class was ready (as after an exercise or break), he first asked students to ”raise their hands.” Unfortunately, a hand ”is lowered” automatically after several seconds. As students raised their hands over a longer interval, the count remained low, leading the instructor to incorrectly believe people had not responded. He switched to posting an interactive slide at the beginning of a break with entries such as ”need more time” and ”ready.” But students marked ”Need more time” and later left their office or fail to change it, again misleading him. Finally he returned to hand raising, in conjunction with the attendance window, which indicates which students have hands up and thus allowed him to survey the entire class or particular students for responses. Instructors often gesture for emphasis or to direct attention to part of a slide. Instructor 1 continued to gesture, but outside camera view. Even when encouraged to use the pointer, at first he rarely did. Instructor 2 said that he normally used his hand to point to places on the slide, but he also used it as time went on. Another failure to adopt an unfamiliar channel was the checkboxes for identifying a lack of clarity or material presented too fast or too slow. Normally, this is communicated tactfully, subtly, and unobtrusively, by puzzled or bored expressions. We found little use of the overt means provided, as have previous researchers for similar features. The greatest uncertainty was with the channels for verbal student feedback. The principal channels are the Q&A window and the public discussion or chat window, augmented by the NetMeeting chat. The instructor could respond by voice, and the telephone was also used. The chat window was also used by the system to report students ‘coming and going.’ Technical failures and rebooting were frequent enough to inject a lot of noise into this channel. But this activity also made it seem to students to be a logical place to report problems, and once attention was focused on it, to ask questions. Instructors, on the other hand, had heavy demands on their attention, and generally stopped monitoring this noisy channel once a class was underway, except during exercises (until Instructor 2 did in his fourth class). Student questions then went unanswered. Initially the Q&A window was unused, which reduced instructor attention to it as well; its first use was when a frustrated student escalated a technical problem from chat to the Q&A window, despite the latter clearly being intended for content questions. By the third class it was used for content questions, with some student voting. For the fourth class in the second course, we asked that technical problems be reported in the NetMeeting chat or by phone, content questions in the Q&A window, and other discussion in the Flatland chat. This brought some order to interaction, but was not adhered to. An interesting observation is that a natural tendency is to respond through the same channel that one is queried. In his first class, Instructor 1 responded to chat questions (at the beginning and during exercises) by typing into the chat window. In the second class he began responding to chat queries over the audio channel. He seemed unaware of having made this shift when queried after the second class. Similarly, an instructor’s first inclination was to try to respond to Q&A window query through the same channel. When an instructor wanted clarification of a question, he had to ask for it verbally. Should the student then respond by entering a non-query in the Q&A window, which everyone was attending to, or through the chat window? They tended to stick with the original channel. For example several students posted responses and clarifications to questions directly in the Q&A window. 5.3.2 Uncertainty about others’ experience Another pervasive challenge is the difficulty of accurately assessing the experience of other system users. This was noted by the Forum developers and has been reported in other groupware assessments. A key to interaction is understanding the contexts of those with whom we interact, the effects of our words and actions in their context and on them, and the sources of the words and actions we experience as changes in our environment. One way to minimize misunderstanding is to minimize the differences among environments. On the other hand, it seems appropriate to customize aspects of instructors’ and students’ windows for their needs, and to provide additional tailorability. But asymmetries caused problems. For example, the instructor could see the slide pointer, but it only appeared on students’ displays when the button was held down. Although informed of this, our instructors forgot by the time they began using the pointer, and believed students could see their gestures. Clarity and speed indicators appeared as checkboxes on student monitors and as meters on the instructor’s. Although they had been informed, students only recalled that the instructor saw something different, and thus could not gauge the effect of their actions or know whether a complaint would be anonymous. When asked to use it they did, but the instructor did nt respond and they stopped. Anonymity is a broader issue. It was unclear whether handraising, Q&A queries, or interactive slide responses are anonymous. In fact, they are not, but it requires an effort to identify actors. An instructor did not realize this and asked students to respond to a potentially critical question. One student alerted others to the lack of anonymity. We customized the instructor’s desktop to include a separate machine for NetMeeting. As a result, during exercises, he put up interactive queries on Flatland, unaware that most students had buried the Flatland window under the NetMeeting window on their single machines. Uncertainty has indirect effects as well. When raised hands, chat questions, or interactive queries are ignored, the initiator does not know if the snub is intentional or not. As noted above, the loss, on the student side, of audio synchrony with NetMeeting displays was not experienced by instructors. They found it difficult to compensate for it even when reminded, and even when they tried to compensate, students detected the mismatch. In general, participants showed a strong assumption that the other people shared their experience. This led to misunderstandings. When it was clear that others did not share experience, this also created uncertainty. 6 DESIGN IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS In the two case studies of Flatland use, we observed trial and error, learning, and increasing comfort with the technology. The underlying system and the interface to it can be improved. We have a better sense of the interaction channels and some of their uses. It is clear that first-time users will not be fluent users of the technology. At the end, our instructors felt it was appropriate only for some courses, and some students had reservations. Where classroom learning is possible it will probably remain more effective. But where it is not, Flatland can be a viable alternative. We have reported a range of specific examples of feature use, and problems using features in isolation or together. Some design guidelines and general observations emerged. One is to minimize confusion through ”What-You-See-IsWhat-I-See (WYSIWIS). Uniformity in the displays for instructor and students contributes to contextual feedback and minimizes uncertainty and confusion. Each participant can understand how their actions are seen by others. Recommended by Isaacs and her colleagues, this cannot be overemphasized. Creating interface ‘affordances’ that suggest to users what particular actions will accomplish, and showing immediate and direct results of actions, are basic tenets of designing single-user interfaces. They are arguably more important in ‘social interfaces’ due to the potential for embarrassment. An example is the tendency to respond in a query channel. Students didn’t seem to mind an instructor answering typed questions by voice, but did resist switching to the chat for followup and acknowledgment. More than one student posted a ”thank you” to the Q&A window. A result of providing multiple channels for interaction to compensate for the lack of face-to-face contact is that the interface is potentially very busy, dispersing attention and leading to overlooked communications. Designers must try to permit as few unneeded distractions as possible. In our case, students found overlapping question entry windows distracting, and instructors often found the chat window distracting. The lack of established protocols adds confusion. Audience feedback often could have streamlined the instructor’s presentation, but wasn’t given. Whether this can be addressed by system design or should be worked out through agreed-upon to social protocols using existing channels remains a research issue. More extensive training sessions will clearly help, but most social protocols probably cannot effectively be taught individually, they will have to be learned through practice. The desire for greater feedback is manifest in the frequent suggestion that audio or video from students to class be added. This would of course create infrastructure and new interface issues. 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank Microsoft Technical Education group for their cooperation in this study. Special thanks to Ushani Nanayakkara for coordinating these online classes and to the instructors, Tom Perham and David Chinn, for volunteering to teach on-line. Thanks to Mary Czerwinski for her help in designing this study and to Ellen Isaacs for sharing her survey questions. We thank the Virtual Worlds Group developing the V-Worlds core on top of which Flatland is implemented. Special thanks to Peter Wong of the Virtual Worlds Group, whose tireless support made these studies possible. 8 REFERENCES 1. Isaacs, E.A., Morris, T., and Rodriquez, T.K., A Forum For Supporting Interactive Presentations to Distributed Audiences, Proceedings of the Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW ’94), October, 1994, Chapel Hill, NC, pp. 405-416 2. Isaacs, E.A., Morris, T., Rodriquez, T.K., and Tang, J.C.(1995), A Comparison of Face-To-Face and Distributed Presentations, Proceedings of the Conference on Computer-Human Interaction (CHI ’95), Denver, CO, ACM: New York, pp. 354-361. 3. Isaacs, E.A., and Tang, J.C, Studying Video-Based Collaboration in Context: From Small Workgroups to Large Organizations, in VideoMediated Communication, K.E. Finn (ed.), 1997, A.J. Sellen & S.B. Wilbur, Erlbaum: city, state , pp. 173-197 4. Begeman, M., Cook, P., Ellis, C., Graf, M., Rein, G. & Smith, T., 1986. Project Nick: Meetings augmentation and analysis. Proceedings of CSCW’96. Revised version in Transactions on Office Information Systems, 5, 2, 1987. 5. Vellon, M., K. Marple, D. Mitchell, and S. Drucker. The Architecture of a Distributed Virtual Worlds System. Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Object-Oriented Technologies and Systems (COOTS). April, 1998. 6. Glenn E. Krasner and Steven T. Pope, "A Cookbook for Using the Model-View-Controller User Interface Paradigm in Smalltalk-80", in Journal of Object-Oriented Programming, 1(3), pp. 26-49, August/September 1988. 7. Microsoft NetShow. Available at http://www.microsoft.com. 8. Microsoft INet SDK. Available at http://www.microsoft.com.