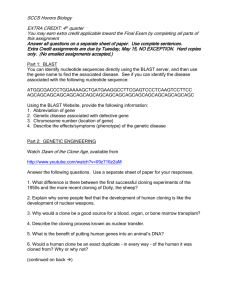

Drama Cloning a Human Being

advertisement

Drama Cloning a Human Being The scene is in the future when cloning has become medically safe but not universally socially accepted. The action takes place in a clinic which is not clearly legal. The authorities in this jurisdiction, however, turn a blind eye to the clinic’s cloning activities. A doctor is interviewing a couple from a neighbouring country where the practice of cloning human beings is prevented. They are seeking to have their dying son cloned. Characters in the drama Dr. Abraham: the doctor assigned to manage the care of Mr. and Mrs. Burke who wish to clone their son Dan who is dying of injuries suffered in an automobile accident. Mr. Burke Mrs. Burke ____________________________ Dr. Abraham: I know this is a difficult time for you, but I must ask certain questions and give you some information. First of all, you should know that cloning human beings has a rather uncertain status in law in our country. While this country is a signatory to a UN declaration against the procedure, still our government has enacted no laws prohibiting cloning people. We have never been bothered by the authorities who are perfectly well aware that our clinic does not just do IVF as advertised. It is in the economic interest of the government to ignore our cloning procedures. Mr. Burke: Yes, yes. We know. I have looked into this carefully. Dr. Abraham: I’m sorry to bother you with these details, but I spoke just to reassure you that you need have no worries about government interference. Since that is not an issue, let’s move on to more important matters. While we are not regulated by law, we do take our moral obligations very seriously. Please don’t take offence, then, if I ask what moves you to take this unusual step, cloning your son Dan. Mr. Burke: We can’t bear it that Dan is dying. Mrs. Burke: (covering her face in her hands) We love him so much. Mr. Burke: We want to have another boy just like him to make the pain less. Dr. Abraham: Why not just have another child? Is there some reason why you want a boy who is like Dan’s identical twin? Mr. Burke: What other reason could we have? . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition Dr. Abraham: Well perhaps Dan is a gifted athlete or exceptionally bright. Perhaps he has some remarkable ability. Mr. Burke: In our eyes he is the best of sons. I suppose other people would just see a nice little boy. We do not expect him to be a genius or a star of some sort. To us, though, he is everything. (Mr. Burke weeps silently.) Dr. Abraham: (gently) Now you have reassured me. There is no better reason than love to do this. Mr. Burke: (with a great effort of self control) Now I have a question for you. Is it safe for my wife and my new son to do this thing? Years ago, I remember hearing of questions raised about dangers for the child who is cloned. I have to ask, because, in my country, they still won’t allow cloning people at all. Dr. Abraham: I can give you complete assurance that the procedure is just as safe as any assisted reproductive therapy. Decades ago, I could not have given you that assurance. Now, however, we have the medical advances and the experience to get uniformly excellent results. Mrs. Burke: Dan is ten years old. Will our baby be born with ten years taken from his life? Dr. Abraham: No, not at all. Once we had a problem with timing device in the cells of the clone, things called telomeres. We solved that problem over forty years ago, and our empirical evidence with animal models and some people shows that clones can expect longer lives and healthier lives than the average person. Mrs. Burke: If it was your son, Dr. Abraham, would you do what we are doing? Dr. Abraham: Yes Mrs. Burke, I would. I know it is done out of love. Love is the very best of motives. Mr. Burke: We have talked to Dan to tell him that maybe he will not survive his injuries. The doctors say he has no chance, but we just told him it is maybe what will happen, and we talked to him about having a little brother just like him. It comforts him a little. He thinks of it as a way he would live on. He tells us to make sure his clone finishes the picture he was drawing for us. Dr. Abraham: I’m not quite sure what to say about that. You and I know your new baby would not be Dan but like a younger brother who is physically just like Dan. In a way, though, I think each of us is related to our earlier selves only by similarity. We may change so much in our minds and abilities. I see some patients in my work at the hospital who are altered mentally to a tremendous degree. Really only the outside, the body, remains to tell us who they are. Physical resemblance is a large part of what we think of as survival. Perhaps it makes very good sense to look at Dan’s younger brother as Dan does – as a kind of continuation of Dan. In any case, as long as it gives him some solace, it is a good way for Dan to think. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition Mrs. Burke: Thank you doctor. It will be a comfort to us all. Dr. Abraham: I would like to leave it at that, but I’m afraid our policies require me to ask a few more questions. From the point of view of our board at the clinic, I have no doubt said too much already about continuing Dan’s life in a manner of speaking. I must correct that now and focus more on what the clinic asks me to explore in this interview. Let’s suppose that your new baby is called “John.” Imagine that when John gets to be ten years old, you give him the picture that Dan was drawing for you and ask him to finish it. Suppose, for whatever reason, he absolutely refuses to do it. How would that strike you? Mr. Burke: I know what you are concerned about doctor. You don’t want us to think of John as just a replacement for Dan. You don’t want us to push Dan’s likes and dislikes on John. We would never do that. We know kids are all different. Dr. Abraham: Yes we are concerned here that any baby born partly as a result of our procedures is loved for his own sake, not just as a reminder of one who died. That is why we always ask these questions. I am told to ask you this as well. What if, through a difficult birth, there was some disfigurement and John did not resemble Dan as much as you hoped? Mrs. Burke: We will love our baby no matter what. We will love him because he is our baby. If he reminds us of Dan, we will only love him all the more. You know doctor, Dan makes me smile because of the way he reminds me of my father, bless his soul. Resemblance to family is a very good thing, but with or without it, we will love our baby as much as a parent can love a child. Dr. Abraham: I don’t doubt it. I must ask these questions because we at the clinic seek to ensure that John will be allowed his own identity and autonomy. We never accept couples who want to force a child to be like someone else, but I can see that is not what you would do. Mr. Burke: Of course not doctor, of course not. We would not compound the tragedy by harming another child. We know this child will not be Dan. We will love him for himself and let him choose his own way. Dr. Abraham: I am sure that you and your new child will bring each other joy. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition Background Information There are several excellent websites on the science and ethics of cloning. See, for instance, The “Ethics Matters” website from the University of San Diego: http://ethics.sandiego.edu/applied/bioethics/ The Genethics website contains many useful links, http://genethics.ca/topics/cloning/ The entry on human cloning on the American Medical Association’s website, http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-science/geneticsmolecular-medicine/related-policy-topics/stem-cell-research/humancloning.shtml The entry on cloning on the Human Genome Project’s website, http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/elsi/cloning.shtml Here is a brief excerpt from the Human Genome Project’s website: “Reproductive Cloning Celebrity Sheep Died at Age 6 Dolly, the first mammal to be cloned from adult DNA, was put down by lethal injection Feb. 14, 2003. Prior to her death, Dolly had been suffering from lung cancer and crippling arthritis. Although most Finn Dorset sheep live to be 11 to 12 years of age, postmortem examination of Dolly seemed to indicate that, other than her cancer and arthritis, she appeared to be quite normal. The unnamed sheep from which Dolly was cloned had died several years prior to her creation. Dolly was a mother to six lambs, bred the old-fashioned way. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition Image credit: Roslin Institute Image Library Reproductive cloning is a technology used to generate an animal that has the same nuclear DNA as another currently or previously existing animal. Dolly was created by reproductive cloning technology. In a process called "somatic cell nuclear transfer" (SCNT), scientists transfer genetic material from the nucleus of a donor adult cell to an egg whose nucleus, and thus its genetic material, has been removed. The reconstructed egg containing the DNA from a donor cell must be treated with chemicals or electric current in order to stimulate cell division. Once the cloned embryo reaches a suitable stage, it is transferred to the uterus of a female host where it continues to develop until birth. Dolly or any other animal created using nuclear transfer technology is not truly an identical clone of the donor animal. Only the clone's chromosomal or nuclear DNA is the same as the donor. Some of the clone's genetic materials come from the mitochondria in the cytoplasm of the enucleated egg. Mitochondria, which are organelles that serve as power sources to the cell, contain their own short segments of DNA. Acquired mutations in mitochondrial DNA are believed to play an important role in the aging process. Dolly's success is truly remarkable because it proved that the genetic material from a specialized adult cell, such as an udder cell programmed to express only those genes needed by udder cells, could be reprogrammed to generate an entire new organism. Before this demonstration, scientists believed that once a cell became specialized as a liver, heart, udder, bone, or any other type of cell, the change was permanent and other unneeded genes in the cell would become inactive. Some scientists believe that errors or incompleteness in the reprogramming process cause the high rates of death, deformity, and disability observed among animal clones. … What are the risks of cloning? Reproductive cloning is expensive and highly inefficient. More than 90% of cloning attempts fail to produce viable offspring. More than 100 nuclear transfer procedures could be required to produce one viable clone. In addition to low success rates, cloned animals tend to have more compromised immune function and higher rates of infection, tumor growth, and other disorders. Japanese studies have shown that cloned mice live in poor health and die early. About a third of the cloned calves born alive have died young, and many of them were abnormally large. Many cloned animals have not lived long enough to generate good data about how clones age. Appearing healthy at a young age unfortunately is not a good indicator of long-term survival. Clones have been known to die mysteriously. For example, Australia's first cloned sheep appeared healthy and energetic on the day she died, and the results from her autopsy failed to determine a cause of death. In 2002, researchers at the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, reported that the genomes of cloned mice are compromised. In analyzing more than 10,000 liver and placenta cells of cloned mice, they discovered that about 4% of genes function abnormally. The abnormalities do not arise from mutations in the genes but from changes in the normal activation or expression of certain genes. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition Problems also may result from programming errors in the genetic material from a donor cell. When an embryo is created from the union of a sperm and an egg, the embryo receives copies of most genes from both parents. A process called "imprinting" chemically marks the DNA from the mother and father so that only one copy of a gene (either the maternal or paternal gene) is turned on. Defects in the genetic imprint of DNA from a single donor cell may lead to some of the developmental abnormalities of cloned embryos. For more details on the risks associated with cloning, see the Cloning Problems links below. Should humans be cloned? Physicians from the American Medical Association and scientists with the American Association for the Advancement of Science have issued formal public statements advising against human reproductive cloning. The U.S. Congress has considered the passage of legislation that could ban human cloning. See the Policy and Legislation links below. Due to the inefficiency of animal cloning (only about 1 or 2 viable offspring for every 100 experiments) and the lack of understanding about reproductive cloning, many scientists and physicians strongly believe that it would be unethical to attempt to clone humans. Not only do most attempts to clone mammals fail, about 30% of clones born alive are affected with "largeoffspring syndrome" and other debilitating conditions. Several cloned animals have died prematurely from infections and other complications. The same problems would be expected in human cloning. In addition, scientists do not know how cloning could impact mental development. While factors such as intellect and mood may not be as important for a cow or a mouse, they are crucial for the development of healthy humans. With so many unknowns concerning reproductive cloning, the attempt to clone humans at this time is considered potentially dangerous and ethically irresponsible. See the Cloning Ethics links below for more information about the human cloning debate.” Cloning: A brief history of scientific and ethical false starts 1890's Jack Loeb, embryologist, clones embryos of sea urchins (the nucleus of one cell was used to create a twin cell). 1928 Hans Spemann, embryologist, transfers the nucleus from a 16 cell salamander embryo to a cell with no nucleus which develops into a salamander. 1952 Robert Briggs and Thomas King transfer blastula nuclei of the northern leopard frog into an enucleated cell, cloning it. Such blastulae develop into tadpoles. Later work succeeds in cloning cells from tadpoles with only a 2% success rate indicating a diminution of genetic potential as the embryo develops. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition 1960's F.E. Steward, cell biologist, Cornell, reproduces a carrot from a differentiated root cell of a carrot and hypothesizes the possibility of cloning adult mammals. 1962 John Gurdon, developmental biologist, Oxford, clones cells from the intestinal lining of tadpoles of the South African frog Xenopus laevis with a 2% success rate. The tadpoles are old enough to begin feeding. It is assumed the intestinal cells are differentiated. Dennis Smith points out that 2% of the cells in the intestine are undifferentiated embryo cells. Gurdon may not have cloned a differentiated cell. 1970's Willard Gaylin, psychiatrist and Daniel Callahan, philosopher, Harvard, use cloning as an Ethical issue in the startup of the Hastings Centre Report, using Steward's work and Gurdon's as evidence in ignorance of the dispute among embryologists about what Gurdon had accomplished. 1971 Nobel laureate James D. Watson warns congress that cloning will soon be possible and that scientists had not fully appreciated what it means to clone a frog or fertilize human eggs in the laboratory. 1971 Patrick Steptoe and Robert Edwards develop IVF. 1974 Gunther Stendt, molecular biologist, Berkeley, writes on the Ethics of cloning in Nature suggesting fear of a Brave New World is irrational given the chance of fashioning utopia using clones. 1977 Karl Illmensee announces cloning three mice. Later, in the early 80' he is suspected of having fabricated the results. Careers are ruined. Scientists disagree on what has been proven. Ethicists are left with uncertain evidence for their warnings again. 1978 Louise Brown is born resulting from IVF. 1978 April Fool’s Day publication of science writer David Rorvik's book In His Image: The Cloning of a Man and the press has a field day. No proof is ever forthcoming of the claim to have cloned a human adult, but . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition public fear, the insularity of scientists, and scientific skepticism are fueled. Ethical debates are conducted about disallowing cloning and other research in reprogenetics. 1980's cloning research driven partly by wishes of cattle companies to multiply prize cows. 1983 Karl Illmensee signs a statement before a committee of the University of Geneva saying "Protocols of Dr. Karl Illmensee have been manipulated in a way which is contrary to scientific ethics in some period of 1982." Illmensee's results are widely held to be a fraud or a fluke. 1983 John A. Robertson, "Procreative Liberty and the Control of Pregnancy, Conception and Childbirth," Virginia Law Review 69 (April 1983) argues against government intervention and in favour of parents' liberty to use reproduction assisting technologies provided there is no substantial harm to others. 1984 After many attempts to replicate Illmensee's results, Davor Solter publishes negative results in Cell and Science claiming that cloning of mammals by simple nuclear transfer is impossible. March 1986 Steen Willadsen announced in Nature that he had cloned sheep from early embryos. Willadsen and Carole B. Fehilly also produced chimeras like a goat/sheep. Fall 1986 Prather, Eyestone and other students in Neal First's lab at the University of Wisconsin Animal Science Lab clone cow embryos. Ian Wilmut hears that Willadsen has cloned 60 to 120 day embryos and gets confirmation from Willadsen. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition 1987 Wilmut gets commercial sponsors and teams up with Keith Campbell to work on cloning sheep to make manufacturing drugs through genetically altered sheep cheaply. 1990's The ethical and scientific discussion of cloning dies down as the topic has acquired a bad name for frauds, flukes and failures among scientists as well as charges of fantasy and fear among ethicists. 1993 George Washington University Researchers clone human embryos and keep them in a Petri dish for days. Some ethicists protest. 1995 Wilmut and Campbell discover that by starving embryo cells and putting them into the G0 state they can get them to accept and use DNA even after they had grown in the laboratory and no longer resembled embryo cells. Some of these cells had differentiated and looked like skin cells. They successfully use differentiated cells to produce two lambs, Megan and Morag in July 1995. 1996 March 7 the results are published in Nature and Davor Solter writes an editorial saying that cloning adult cells will be more difficult but can no longer be considered impossible. His plea for debate on how to use this knowledge is largely ignored. Ethicists and scientists sleep through the event. 1996 July 5, Dolly is born, apparently cloned from adult udder cells, the first mammal cloned from an adult. 1997 In February the news of Dolly is revealed. Ethicists and scientists are stunned. 1998 By February Wilmut admits there is a remote possibility that the cell from which Dolly was produced came from a fetus rather than an adult. The sheep from which the cells to clone Dolly were taken was pregnant. Fetal cells can be present in the circulatory system of such an animal Wilmut concedes. At least three labs fail in the attempt to duplicate Wilmut and Campbell's work. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition Similarities to Gurdon's disputed cloning of frogs in the 60's seem evident. Ethicists are called upon to revisit cloning are sensitive to criticism about jumping the gun with earlier unconfirmed cloning cases; many keep their powder dry and wait. 1998 University of Hawaii researchers adapt Wilmut's method cloning a mouse dozens of times and creating three generations of cloned clones. 1998 Kinki University researchers produce eight calves cloned from an adult cow. Ethicists must now put forward their views on cloning. There is little doubt that cloning of adult human beings is possible. 1999 Cloned animals may currently have a foreshortened life span and increased susceptibility to disease since their cells do not have fresh telomeres like a newborn but shortened telomeres like those of the genetic parent. Telomeres are biological markers on DNA thought to indicate the time remaining until the organism will die. (Vancouver Sun, May 27, 1999, page 1, Nature May 27, 1999) 2000 Several proposals for cloning clinics to help childless individuals have genetically similar offspring have been proposed. One of these is for the US city of Chicago. 2006 A listing of current risks of cloning can be found at http://gslc.genetics.utah.edu/units/cloning/cloningrisks/ Sources Gina Kolata Clone: The Road to Dolly and the Path Ahead. New York: William Morrow and Co. 1998 . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition Julie McDonald Contemporary Moral Issues in a Diverse Society. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth 1998 The Vancouver Sun Wednesday, February 18, 1998 p. A4. Time Canadian Edition January 11, 1999. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition Ethical Theories Utilitarianism a) Act utilitarianism The right actions are the ones in accord with the principle of utility; that is, the ones that create the greatest happiness or pleasure and the least unhappiness or pain for all sentient beings affected by those actions. In this case, the act utilitarian will look at the expected consequences of cloning Dan vs. the expected consequences of not cloning him. On the assumption that the technical difficulties involved in cloning have been solved and that Mr. and Mrs. Burke are accurately reporting that they will love and care for their cloned infant, it appears that the greatest good would come from cloning Dan (the infant will, presumably, have a happy life, and the parents will feel much happiness from having a baby who is the genetic twin of their beloved, Dan) and so it would be morally right to do. It could be argued, however, that the act that would produce the greatest good and so the act that would be right, according to act utilitarians, would be if the Burke’s did not clone their dying son. Instead, they should adopt and care for an already living child who is in need of a good home. Further, they should take the money they would have spent on cloning, and use it instead to assist people who were already alive and who are in need of help. Because there is so much need in the world, it may be that more happiness can be brought about by this means than by making the Burke family happy by having a clone of Dan. b) Rule utilitarianism Rule utilitarians claim that the right act follows the best set of rules, and the best set of rules is the one that, if consistently followed, will produce the greatest amount of happiness, and the least amount of unhappiness, for everyone affected by those rules. According to rule utilitarians, we need to consider then not only the consequences of cloning in the Burke’s case, but the consequences of cloning humans in general. Here much will depend on the effectiveness of regulating the technology. If rules could be implemented that allowed cloning humans only when it could be done safely and for parents who would love and care for their cloned children, then perhaps cloning humans would be justified. If however, cloning humans would lead to net negative consequences – say in the way clones or non-cloned infants were valued – then rule utilitarians would be expected to view cloning humans in this case, and in general, as morally wrong. Rule utilitarians would also want to consider whether it would be better for human happiness, on balance, to support policies promoting adoption rather than reproduction through human cloning. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition Kantian Rights Theories Kant defends the following two principles of right action: Act only according to those maxims that can, at the same time, be consistently willed as a universal law. Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or the person of another, always as an end and never merely as a means. According to Kant, these principles are equivalent: they always give the same moral guidance. But what do these principles imply about the morality of the Burkes cloning their dying son? First, we might ask if this proposal involves maxims (principles) that can be universally (i.e., consistently) willed. Suppose the parents’ maxim is “to clone their dying child so that they could have another child that they could love.” It seems that there is no contradiction in a universal law that says that everyone may clone their dying child to have another child that they would love. If this is right, then their action would be morally permissible. It appears that the same answer is reached when we ask whether anyone is being treated merely as a means in this case. To apply this principle, we must consider whether any rational being is being treated as a mere thing. The child, Dan, who is only 10 years old, is arguably not a rational being, so the principle of always treating rational beings as ends in themselves would not apply to him. But even if Dan is viewed as a rational being, it is important to note that in this case Dan’s parents obtain Dan’s permission to clone him to make a genetic copy. Thus, again, he is not being improperly treated on Kant’s view. In obtaining his consent, they are treating him with respect for his rational nature. One might worry that the cloned child is being disrespected in this case. But that is doubtful: his parents assure Dr. Abraham that their child will be loved for his own sake, and that his autonomy will be respected as he matures. A Kantian might have a different reaction to cloning, however, if the facts were different. If an adult was to be cloned without his consent, then a Kantian would surely object to the procedure. For this would treat the adult merely as a means. Similarly, a Kantian could perhaps argue that it would be wrong to clone a human being if the clone was unlikely to lead a rational autonomous life, either because the clone would lack rational capabilities or because the clone would not be allowed to live autonomously. It might seem that the Kantian principle – never to treat humanity merely as means – would rule out cloning in this case. For it might appear that the parents are seeking to have a child merely as a means to dealing with their own loss and grief. Since it is wrong to use people merely as means, it may seem clear that it is wrong to clone in this case. This is probably too simplistic, however. For people often have children for all sorts of reasons – to become a parent, to have someone to love, to carry on one’s family name, to have someone to help with family finances, . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition etc – yet we tend not to view those acts as morally wrong. Indeed, as long as the child is loved for her or his own sake and will be capable of leading a decent life, we tend to view having a child as morally permissible, even if the child is wanted for other reasons. Likewise, in this case, as long as the cloned child can be expected to be loved and respected for his own sake, the fact that the parents are also having a child as a way to try to cope with their grief does not make their choice wrong. Intuitionist Rights Theories Morality consists in following a variety of prima facie duties, each of which is self-evidently true. We use judgment to determine which prima facie duty is most pressing in a given situation – the right thing to do is to follow the most pressing prima facie duty in that situation. In this case, compassion and autonomy speak in favour of the permissibility of the parents’ decision to clone their dying child. It could be argued that a duty of loyalty to their dying child, Dan, speaks against cloning him. But that is questionable: for they are not turning their back on their son, but rather they are trying to be loyal to his memory by having a child “in his image”. What might also think that cloning in this case is wrong because it violates the duty to not play God or the duty to accept death. But it seems wrong to claim that there are such duties. For not only are such duties far from self-evident, but it is doubtful that they are duties at all. We permissibly play God (modern medicine) and often do not accept death (resuscitation; saving those who are drowning; etc.), so the claim that there are such duties appears to be false. If cloning as a policy turns out to be harmful to society, then that would certainly constitute a reason for deontologists to oppose such a policy. For example, if, as a result of cloning, people come to be thought of as replacable types rather than as individuals, then this would constitute a strong reason against the permissibility of cloning humans. Social Contract Theories Contractarians ask us to follow the rules of the ideal social contract. We discover what these rules are by asking what rules people in the original position would choose. The original position is a hypothetical situation in which people are: 1. equally powerful (so nobody can force others to accept a rule) 2. equally intelligent (so nobody can trick others into accepting a rule) 3. self-interested (so no other moral theory enters Social Contract Theory in a Trojan Horse) 4. ignorant of their own advantages and disadvantages (Behind a veil of ignorance participants cannot skew the rules in their own favor or the favor of their group.) People in the original position would seek to promote their interests, without knowing what position in society they would occupy. They do not know if they will be a person, like Mr. or Mrs. Burke, who wants to clone their dying child; a person, such as Dan, who is dying; a researcher; or a clone. Given this uncertainty, people in the original position will want autonomy to make their own reproductive decisions, but they will also want safeguards to protect the vulnerable from harm. If cloning could be implemented, and abuses controlled, then it seems . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition like people in the original position would support such a policy, and would view the Burkes’ cloning of Dan as permissible. If cloning would be expected to lead to serious abuses – either to clones or to respect for humans generally – then people in the original position might reasonably opt to protect the vulnerable and to oppose cloning. As with many of the other theories we have been considering, much will depend on the facts of whether cloning can be safely implemented. Virtue Ethics and Care Ethics The right actions are the ones that a virtuous person would do. A virtuous person, of course, is one who possesses virtues. The virtues are positive character traits, manifested habitually, that enable one to live a good life. For Aristotle, these virtues are said to be in the mean between two extremes. For example, courage is the mean between the extremes of cowardice and being rash. And courage is a virtue because it is a character that enables a person to overcome life’s challenges and to live well. The virtue of compassion speaks heavily in favour of the permissibility of cloning in the Burkes’ case. The Burkes also do not seem to be behaving irresponsibly or selfishly in this case, and they are certainly motivated by love. However, if the facts of the case were different, say because the telomere and other technical problems had not been solved, then these same virtues would speak heavily against cloning humans. Perhaps humility (which might involve acceptance) may be a virtue that speaks against cloning in this case, and against cloning in general, though that is debatable. Perhaps the more charitable thing to do would be to adopt an existing child rather than cloning, but it is not clear that this is enough to make cloning Dan wrong (or vicious) in this case. For, in general, people could adopt rather than have a biological child, and yet most do not view their decision to have a biological child as vicious. . Smolkin, Bourgeois & Findler: Debating Health Care Ethics, 1st Canadian Edition