Pronouns - HomePage Server for UT Psychology

advertisement

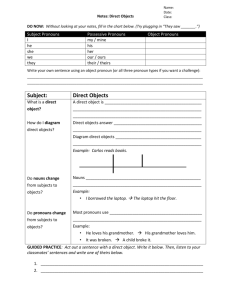

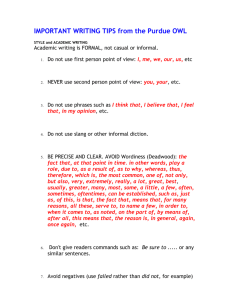

Psy394v The Social Psychology of Language Use Oct 15, 2001 Some Psychological Perspectives on Pronouns Kashima, E. S., & Kashima, Y. (1998). Culture and language: The case of cultural dimensions and personal pronoun use. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 461 – 486. - Analyzed cultural differences between countries with languages that have a ‘pronoun drop’ option (such as Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Mandarin, Indonesian, Korean, Russian, etc .) and that don’t have a ‘pronoun drop’ option (e.g. English, German, French, Greek, Finnish, etc. ). - Pronoun drop option refers to the possibility in spoken language to express first and second person perspective without the explicit use of “I” or “you” - The idea is that an explicit use of “I” and “you” highlights a figure against the speech context that constitutes the ground; the absence reduces the prominence of the speaker; consequently, the authors hypothesize that countries with a pronoun drop language tend to be more collectivistic as compared to countries with languages with obligatory pronoun use. This should be the case because implicitly in a conversation less ‘overt’ distinctions are made between speakers, less emphasis is put on the different perspectives. - Across 71 countries and 39 languages indicators of individualism-collectivism (Hofstede, 1980) correlated with the type of language in the direction that pronoun drop countries were less individualistic - Other results: Pronoun drop goes with more power distance, more paternalism, more conservatism, more moral discipline and less achievement orientation. Sillars, A., Wesley, S., McIntosh, A., Pomegranate, M. (1997). Relational characteristics of language: Elaboration and differentiation in marital conversation. Western Journal of Communication, 61, 403 – 422. - Adopt the theoretical notion that personal references in marital conversations can reflect the degree of differentiation (integration) of identities with “we” pronouns showing greater inclusion/ integration and “I/you” pronouns establishing greater separation of self and other. - Transcripts of 120 married couples discussing marital issues such as “disagreement about money”, “lack of communication”, or “disagreement about household responsibilities” were analyzed in terms of pronoun use (word count of “I”, “I’m” or “my” or “we”, “ours” or “each other”); questionnaires were used to classify couples according to interdependence/autonomy and marital ideology (traditional); ultimately classification into four types: traditional, independent, separate and mixed. - Results show that “I” and “you” words correlate negatively with satisfaction, “we”-words positively with age and “you” words negatively with educational level. Also, traditional/ interdependent couples used less “I” and “you” words as compared to autonomous couples. - Other results: more satisfied couples made more cross-references (repetition of what the other person said) and avoided making statements about the other (interpretation). Also, more educated couples had longer utterances, more qualifiers (sort of, maybe, probably, seems to me) and more meta-talk. 1 Psy394v The Social Psychology of Language Use Oct 15, 2001 Cegala, D. J. (1989). A study of selected linguistic components of involvement in interaction. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 53, 311 – 326. - Sought out to identify linguistic correlates of engagement / detachment in a communication; the authors primarily looked at four linguistic concepts: Verbal immediacy, uncertainty, pronoun use (first singular – plural; ratio second/first singular and first plural/first singular) and article use (a, an vs. the – the implies more shared knowledge) - 120 (60 males, 60 female) participants who did not know each other are asked to engage in a brief conversation (6 min; same sex dyads) talking about what ever they want. Participants were preselected on the basis of extremity of IIS scores (Interaction Involvement Scale (trait characteristic; Cegala, 1981, 1982). Groups with high-high, low-low and high-low involvement dyads - Results show that high involvement in interaction is characterized by high certainty expression, highly immediate language and more relational pronouns (smaller first person ratio: H-H dyads used more than H-L and H-L dyads) Schütz, A., & Baumeister R. (1999). The language of defense: Linguistic patterns in narratives of transgression. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 18, 269 – 286. - investigated how defensive motivation affects pattern of language use; narratives of personal transgressions (about hurting someone) were compared against narratives of making someone happy. - Compared to happy stories, transgression narratives were more likely to describe actions occurring without deliberate intention (“it happened” vs. “I decided to”). - Also: transgression narratives had shorter sentences, a longer introduction (to carefully explain the background?) and focused more on the emotions and thoughts of the narrator whereas ‘making someone happy’-narratives focused more on the emotions and thoughts of the target; transgression narratives had fewer specific details. Perdue, Charles W; Dovidio, John F; Gurtman, Michael B; Tyler, Richard B. Us and them: Social categorization and the process of intergroup bias. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 59, 475-486. Participants responded more quickly to positive words such as "sunshine" when they followed the ingroup pronoun "we" than they had if the out-group pronoun "they" was used. The authors suggest that the actual words that designate in-groups/out-groups automatically introduce evaluative intergroup biases that favor the in-group. Therefore, if we have a difficult time describing other groups by not using the words "we" or "they" we should be aware of the linguistic influences that may help contribute to misperception between groups. 2 Psy394v The Social Psychology of Language Use Oct 15, 2001 WHAT IS A PRONOUN, ANYWAY? First you need to know about anaphor. An anaphor is a linguistic unit that refers to objects that have already been introduced into a discourse. So anaphors refer to something previously mentioned; cataphors refer to something that will be mentioned later. Both anaphors and cataphors are collected under the term endophora. Endophora share their boundedness to a text, often of only sentence length. This contrasts with exophora, AKA deictic units, which refer to an extra-linguistic situation. In other words, 1. Endophora – referents occur within the text a. Anaphor – referent is something previously mentioned. Includes pronouns b. Cataphor – referent is something not yet mentioned, but will be mentioned later. 2. Exophora (deictic units) – referents occur outside the text Linguists tend to treat pronouns as literally standing in place of nouns, and are apparently uninterested in their role as indexical indicators of persons. ******** Grammarians classify pronouns into several types, including the personal pronoun, the demonstrative pronoun, the interrogative pronoun, the indefinite pronoun, the relative pronoun, the reflexive pronoun, and the intensive pronoun. Personal Pronouns A personal pronoun refers to a specific person or thing and changes its form to indicate person, number, gender, and case. Subjective Personal Pronouns: A subjective personal pronoun indicates that the pronoun is acting as the subject of the sentence. The subjective personal pronouns are “I,” “you,” “she,” “he,” “it,” “we,” “you,” “they.” Objective Personal Pronouns: An objective personal pronoun indicates that the pronoun is acting as an object of a verb, compound verb, preposition, or infinitive phrase. The objective personal pronouns are: “me,” “you,” “her,” “him,” “it,” “us,” “you,” and “them.” Possessive Personal Pronouns: A possessive pronoun indicates that the pronoun is acting as a marker of possession and defines who owns a particular object or person. The possessive personal pronouns are “mine,” “yours,” “hers,” “his,” “its,” “ours,” and “theirs.” Note that possessive personal pronouns are very similar to possessive adjectives like “my,” “her,” and “their.” 3 Psy394v The Social Psychology of Language Use Oct 15, 2001 A Chart of Pronoun Cases Subjective Objective Possessive I Me My, Mine You You Your, Yours He Him His She Her Her, Hers It It Its We Us Our, Ours They Them Their, Theirs Demonstrative Pronouns A demonstrative pronoun points to and identifies a noun or a pronoun. “This” and “these” refer to things that are nearby either in space or in time, while “that” and “those” refer to things that are farther away in space or time. The demonstrative pronouns are “this,” “that,” “these,” and “those.” “This” and “that” are used to refer to singular nouns or noun phrases and “these” and “those” are used to refer to plural nouns and noun phrases. Note that the demonstrative pronouns are identical to demonstrative adjectives, though, obviously, you use them differently. It is also important to note that “that” can also be used as a relative pronoun. Interrogative Pronouns An interrogative pronoun is used to ask questions. The interrogative pronouns are “who,” “whom,” “which,” “what” and the compounds formed with the suffix “ever” (“whoever,” “whomever,” “whichever,” and “whatever”). Note that either “which” or “what” can also be used as an interrogative adjective, and that “who,” “whom,” or “which” can also be used as a relative pronoun. You will find “who,” “whom,” and occasionally “which” used to refer to people, and “which” and “what” used to refer to things and to animals. “Who” acts as the subject of a verb, while “whom” acts as the object of a verb, preposition, or a verbal. Relative Pronouns You can use a relative pronoun is used to link one phrase or clause to another phrase or clause. The relative pronouns are “who,” “whom,” “that,” and “which.” The compounds “whoever,” “whomever,” and “whichever” are also relative pronouns. 4 Psy394v The Social Psychology of Language Use Oct 15, 2001 You can use the relative pronouns “who” and “whoever” to refer to the subject of a clause or sentence, and “whom” and “whomever” to refer to the objects of a verb, a verbal or a preposition. Indefinite Pronouns An indefinite pronoun is a pronoun referring to an identifiable but not specified person or thing. An indefinite pronoun conveys the idea of all, any, none, or some. The most common indefinite pronouns are “all,” “another,” “any,” “anybody,” “anyone,” “anything,” “each,” “everybody,” “everyone,” “everything,” “few,” “many,” “nobody,” “none,” “one,” “several,” “some,” “somebody,” and “someone.” Note that some indefinite pronouns can also be used as indefinite adjectives. Reflexive Pronouns You can use a reflexive pronoun to refer back to the subject of the clause or sentence. The reflexive pronouns are “myself,” “yourself,” “herself,” “himself,” “itself,” “ourselves,” “yourselves,” and “themselves.” Note each of these can also act as an intensive pronoun. Intensive Pronouns An intensive pronoun is a pronoun used to emphasize its antecedent. Intensive pronouns are identical in form to reflexive pronouns. (e.g., I myself believe that aliens should abduct my sister.) AND HERE THEY ARE…… I Disruptions of correct usage of “I” signal psychopathology. Schizophrenics display pronoun disruption of this pronoun, in particular (according to some researchers, but not others). It is also curiously used among individuals with dissociative identity disorder. Personal pronouns are central to the human self system. In particular, it is the self-referential function of the first person pronoun that allows each of us to assert possession of brains, breath, beauty, buttons, brothers, etc. in a uniform way. To understand brains, breath, beauty, buttons, and brothers, one needs to understand anatomy and physiology, aesthetics, tailoring, and psychology. To understand how one asserts a claim on each of them one need only understand language. Thus I'm not concerned with understanding the "brother" component of the phrase "my brother." I'm only interested in the "my" component, which functions the same in that phrase as it does in similar phrases such as "my body," "my brain," or, for that matter, "my button." Language constitutes us as subjects or persons, the sort of beings who can communicate. The I or Ego is the being who can say "I" or "Ego." But "I" is inherently a contrastive term, linked by contrast with a "not-I," an "other"--in communication, a "you." I become a person or subject by assuming the first-person pronoun position in the language I use. I assume personhood by saying "I." To be a person is to be able to use the first-person pronoun "I." But again, "I" is an implicitly contrastive term. It implies a "you"--a "you" who can also be an "I." A subject who says "I" 5 Psy394v The Social Psychology of Language Use Oct 15, 2001 implicitly addresses a "you." To function as a subject (a person) is to function in an inter-subjective context. To assume the first-person position in language is to assume a position defined by contrast with the second-person position. This contrast is, moreover, of a particular kind: it is the contrast of two polar terms that are not opposed to one another but have a "dialectical" relation to one another--a relation of reciprocity, mutuality. To be a person is to be sometimes in the firstperson ("I") position, and sometimes in the second-person ("you") position. YOU Mead (1934) and social constructionists after her agree that the grammar of the I-you discourse is a basic structural component of human thought. “You” is the pronoun that expresses social relations, particularly in other languages than English. There are lots of theoretical explanations for the loss of the social relations aspect of ‘you’ in English. Most of the ones I read have their basis in religious practices. (e.g., Quakers and Mennonites refused to use two versions of ‘you’ because they rejected social hierarchy.) These issues offered a brief revival of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis: which came first? A social structure that required two versions of this pronoun, or two version of this pronoun created the social structure? WE “We” can be both inclusive (e.g., “Let’s go to the dance, shall we?”) and exclusive (e.g., “We’ve enjoyed meeting you.”) “We” serves a directive function, designed to get others to perform an action that is in the speaker’s own interest. (e.g., “We don’t want to make a fuss at bedtime, do we?”) “We” is used to illustrate solidarity. This is frequently done in product marketing as advertisers try to bring about a feeling of solidarity between customer and product or brand name. The customer is intended to be part of the referential sphere of “we.” YOURS and MINE There is some developmental evidence that personal pronouns may have developed later out of possessive ones. Other languages have a variety of possessive pronouns that relate to (1) the nature of the possessor, (2) the nature of the possessed, and (3) the nature of the relationship between the two. English has only the minimal number of distinctions. HE, SHE, or IT Everything I read about this category of pronouns had to do with the gender of nouns, and the use of masculine pronouns as markers for all people. 6