Composite

advertisement

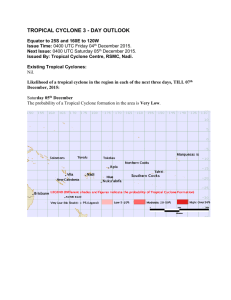

5. Case Study Analyses of Three Cutoff Cyclone Events 5.1 The 2–3 February 2009 Cutoff Cyclone Event 5.1.1 Event Overview The 2–3 February 2009 cutoff cyclone event was associated with difficult-toforecast precipitation and was considered a precipitation forecast bust for the Northeast US, since heavy precipitation greater than 25 mm was forecast to occur but most locations in the region received less than 5 mm. Forecast errors were mainly due to large disagreement between NWP models in the speed, track, and intensity of the surface cyclone (e.g., Grumm et al. 2009; Stuart 2009). As an example, the Global Ensemble Forecast System (GEFS) MSLP forecast valid 1200 UTC 3 February 2009 showed large spread among ensemble members 108 h prior to the validation time, with the largest variability (8–16 hPa) evident throughout eastern New York and western New England (Fig. 5.1a). Uncertainty in the location of the surface cyclone decreased as 1200 UTC 3 February 2009 approached; however, considerable variability among ensemble members was still apparent (Figs. 5.1c,e). In addition, the average of all ensemble members indicates that the forecast surface cyclone was initially located along the East Coast (Fig. 5.1b), but as the forecast projection decreased the location of the surface cyclone was forecasted farther east, over the Atlantic Ocean (Figs. 5.1d,f). On 2 February 2009, a large-scale trough at 500 hPa moved eastward across the northern US and stalled over the Great Lakes (not shown). Figure 5.2 shows the mean 69 500-hPa geopotential height field for the 24-h period (0000 UTC 3 February–0000 UTC 4 February 2009) during which the cutoff cyclone was within the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain. The track of the 500-hPa cutoff cyclone indicates that the cyclone developed and became cut off upstream of the large-scale trough at 0000 UTC 3 February 2009 (Fig. 5.2). The cutoff cyclone slowly moved southeastward around the base of the large-scale trough and then moved northeastward, remaining over the Great Lakes for the duration of its lifetime in the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain. At 0600 UTC 4 February 2009, the cyclone became reabsorbed into the large-scale flow and no longer met the criteria to be considered a cutoff cyclone. The two-day NPVU QPE for 2–3 February 2009 indicates that the precipitation associated with this cutoff cyclone event was confined to coastal regions (Fig. 5.3). Most regions received 2–10 mm, while Cape Cod and Maine received 10–15 mm of precipitation. Most of the precipitation associated with this cutoff cyclone event fell in the 6-h periods following 1800 UTC 3 February 2009 and 0000 UTC 4 February 2009; therefore, in the following section the focus will be on examining the upper-level, midlevel, and low-level tropospheric conditions at these times to determine the synopticscale and mesoscale features that contributed to the observed precipitation. 5.1.2 Meteorological Conditions During the 2–3 February 2009 cutoff cyclone event, a dual jet streak was evident at upper levels, with wind speeds greater than 75 m s−1, or 146 kt (Figs. 5.4a,b). The position of the dual jet streak at 1800 UTC 3 February 2009 was consistent with 70 divergence over eastern Maine, in association with the poleward exit region of the southern jet streak and the equatorward entrance region of the northern jet streak (Fig. 5.4a), which provided conditions favorable for ascent over the region of heavy precipitation. The dual jet streak weakened and was located farther east by 0000 UTC 4 February 2009 and the associated region of divergence was no longer located over the Northeast US at this time (Fig. 5.4b). At midlevels, there was cyclonic absolute vorticity advection over Pennsylvania and New Jersey at 1800 UTC 3 February 2009, downstream of a lobe of moderate cyclonic absolute vorticity, on the order of 16–20 10−5 s−1 (Fig. 5.5a). At 0000 UTC 4 February 2009, the lobe of cyclonic absolute vorticity moved northeastward around the cyclone center and there was cyclonic absolute vorticity advection over southern New York and Connecticut (Fig. 5.5b). By application of the traditional form of the QG omega equation (Eq. 4.1), differential cyclonic vorticity advection, inferred from the cyclonic vorticity advection at 500 hPa, contributed to favorable QG forcing for ascent throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and southern New England, and likely acted to support precipitation in those regions. Further examination of Fig. 5.3 reveals that the regions of 500-hPa cyclonic absolute vorticity advection were in fact collocated with the band of light precipitation (2–10 mm) extending from eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey northeastward into western Massachusetts. However, there was little, if any, contribution to QG forcing for ascent by the Laplacian of temperature advection, as inferred from the 850-hPa temperature and wind fields at 1800 UTC 3 February 2010 (Fig. 5.6). For example, across Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and southern New England, the northeasterly flow at 850 hPa was weak (<20 kt or 10 m s−1), resulting in 71 little or no temperature advection in those regions. The 700-hPa Q-vector analyses at 1800 UTC 3 February 2009 and 0000 UTC 4 February 2009 confirm there was QG forcing for ascent, indicated by Q-vector convergence, across regions of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York (Figs. 5.7a,b). In addition, there was also Q-vector convergence over Cape Cod and Maine at 1800 UTC 3 February 2009 (Fig. 5.7a), where the heaviest precipitation was observed with this event. During the 2–3 February 2009 cutoff cyclone event, there was very little support for precipitation at low levels. The observed surface cyclone was located over the western North Atlantic Ocean, southeast of Cape Cod (Fig. 5.8), suggesting that surface fronts did not play a role in enhancing precipitation across the Northeast US during this event. PW values throughout the entire Northeast US were less than 12 mm, except in Cape Cod where PW values were 12–16 mm (Fig. 5.8), which corresponded to +0.5 to +1.0σ (not shown). In addition, the northeasterly flow across the Northeast US resulted in little PW transport into the region. The lack of low-level forcing for ascent and low PW values likely contributed to the low precipitation amounts that were observed with this cutoff cyclone event. 5.1.3 Conceptual Summary A schematic diagram of the key synoptic-scale features that contributed to the precipitation associated with the 2–3 February 2009 cutoff cyclone event is presented in Fig. 5.9. The precipitation observed in eastern Maine was supported by ascent associated with a dual jet streak at 250 hPa. Light precipitation extending from eastern 72 Pennsylvania and New Jersey northeastward into western Massachusetts was located in a region of inferred differential cyclonic vorticity advection ahead of a lobe of cyclonic absolute vorticity southeast of the 500-hPa cutoff cyclone center, which likely contributed to QG forcing for ascent. There was little or no low-level support for precipitation, with little or no temperature advection at 850 hPa and low PW values observed throughout the Northeast US. The cutoff cyclone would have been placed into the “LP positive trough” composite category throughout the duration of its lifetime in the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain, since it involved a cutoff cyclone embedded within a large-scale trough and less than 25 mm of precipitation was observed in the Northeast precipitation domain. Comparing the event schematic diagram (Fig. 5.9) to the schematic for the “LP positive trough” category (Fig. 4.5f), it is evident that there was a difference in the location of the 500-hPa cutoff cyclone. At 1800 UTC 3 February 2009, the cutoff cyclone was located farther south and west than the composite cutoff cyclone. In addition, the surface cyclone at 1800 UTC 3 February 2009 was located a greater distance to the east of the midlevel cyclone than the “LP positive trough” composite surface cyclone. 5.2. The 1–4 January 2010 Cutoff Cyclone Event 5.2.1 Event Overview The 1–4 January 2010 cutoff cyclone event was a long duration event with varying daily precipitation distributions throughout its lifetime. This cutoff cyclone event 73 was also associated with record-breaking snowfall observed in Burlington, VT, with total of 37.6 in. (95.5 cm) observed for 1–3 January 2010 (e.g., Sisson 2010). Numerical models showed considerable variability in forecasting the precipitation distribution leading up to the event (e.g., Stuart 2010a). The NAM apparently forecast the precipitation best, capturing the terrain enhancement just prior to the event, but QPF amounts were higher than observed precipitation amounts. The 1–4 January 2010 cutoff cyclone originated from a preexisting trough over central Canada and entered the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain at 0000 UTC 2 January 2010 (Fig. 5.10). Throughout the cutoff cyclone event, a highly amplified ridge associated with a large-scale blocking pattern and the negative phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) was in place over Greenland (e.g., Sisson 2010). Studies have found that the negative phase of the NAO is typically associated with a meridional flow regime across the Northeast US, associated with blocking over the North Atlantic Ocean, which results in troughing and colder than normal temperatures along the East Coast (e.g., Bradbury et al. 2002, Stuart and Grumm 2006). During the 1–4 January 2010 cutoff cyclone event, the highly amplified ridge likely contributed to the cutoff cyclone stalling over the western Atlantic Ocean at 0000 UTC 3 January 2010 and retrograding into the Gulf of Maine (Fig. 5.10). At 0000 UTC 4 January 2010 the cutoff cyclone began moving northeastward before finally exiting the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain at 1800 UTC on the same day. The four-day NPVU QPE for 1–4 January 2010 indicates that heavy precipitation (>25 mm) occurred throughout most of Maine in addition to the western slopes of the Green Mountains and the Berkshires (Fig. 5.11). Lake-effect snow off of Lakes Erie and 74 Ontario and Lake Champlain contributed to the heavy precipitation observed in western New York and the Champlain Valley, respectively. During this cutoff cyclone event, the precipitation distributions varied considerably from one cutoff cyclone day to the next (Figs. 5.12a–d). On 1 January 2010, light precipitation (5–10 mm) occurred throughout New England, with 10–20 mm of precipitation observed in southern Maine (Fig. 5.12a). The heaviest 24-h precipitation associated with this event occurred on 2 January 2010 (Fig. 5.12b). On this day, 15–30 mm of precipitation was observed throughout most of Maine, while 10–15 mm of precipitation was observed in regions of northern New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire. Precipitation throughout the Northeast US was once again light on 3 January 2010, with 5–10 mm of precipitation observed across New England, western New York, and the Champlain Valley (Fig. 5.12c). On 4 January 2010, the persistent precipitation was nearing an end, with little or no precipitation associated with the cutoff cyclone observed in the Northeast US (Fig. 5.12d). The focus of the following sections will be on examining the synoptic-scale and mesoscale features that contributed to the varying precipitation distributions on 2 and 3 January 2010, while 1 and 4 January 2010 will not be discussed. 5.2.2 Meteorological Conditions: 2 January 2010 The heaviest precipitation on 2 January 2010 occurred in the 6-h periods following 0000 UTC and 0600 UTC 3 January 2009. Therefore, in order to identify synoptic-scale and mesoscale features that contributed to the heavy precipitation (15–30 mm) in Maine and the moderate precipitation (10–15 mm) in northern New York, 75 Vermont, and New Hampshire (Fig. 5.12b), the upper-level, midlevel, and low-level tropospheric conditions at these times will be discussed. At upper levels, the large-scale trough and embedded cutoff cyclone was negatively tilted at 0000 UTC 3 January 2010 and a developing easterly jet was evident poleward of the cutoff cyclone (Fig. 5.13a). At 0600 UTC 3 January 2010, the region of heaviest precipitation in Maine was located in a region of divergence associated with the equatorward exit region of the easterly jet streak (Fig. 5.13b), which likely contributed to ascent over this region. In addition, the 250-hPa zonal wind poleward of the cutoff cyclone exceeded −3σ at 0000 UTC 3 January 2010 (Fig. 5.14), therefore satisfying the −2.5σ threshold determined by Stuart and Grumm (2004, 2006) to be representative of cyclones that are purely cut off from the background westerly flow. At midlevels, a weak lobe of cyclonic absolute vorticity (16–20 10−5 s−1) extending along the Massachusetts coast, west of the 500-hPa cutoff cyclone center, was evident at 0000 UTC 3 January 2010 (Fig. 5.15a). At 0600 UTC 3 January 2010, the lobe of cyclonic absolute vorticity had strengthened considerably and had moved slightly westward (Fig. 5.15b). The precipitation in New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire occurred downstream of this lobe in a region of inferred differential cyclonic absolute vorticity advection, which likely contributed to favorable QG forcing for ascent over the region. At 0000 UTC 3 January 2010, the 850-hPa northeasterly and easterly flow poleward of the cutoff cyclone advected warm air into regions of northern Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire (Fig. 5.16). It can be inferred that the Laplacian of warm air was maximized in this region of warm air advection, which would have further contributed to QG forcing for ascent in Vermont and New Hampshire. Q-vector analyses 76 indicate that 700-hPa Q-vector convergence was maximized (2–4 10−12 Pa m−2 s−1) over Maine and northern regions of New Hampshire and Vermont at 0000 UTC and 0600 UTC 3 January 2010, respectively (Figs. 5.17a,b), further confirming that precipitation in these regions was supported by QG forcing for ascent. At 0000 UTC 3 January 2010, a region of 925-hPa frontogenesis along a warm front was evident in eastern Maine (Fig. 5.18a). At 0600 UTC 3 January 2010, the region of frontogenesis had strengthened and moved southwestward across Maine (Fig. 5.18b). A cross section at 0600 UTC 3 January 2010 shows two regions of frontogenesis located between 500 and 600 hPa and near the surface (Fig. 5.18c), suggesting that there was forcing for ascent associated with frontogenesis at both midlevels and low levels, which likely enhanced the precipitation over Maine. Also at low levels, anomalous PW (+1 to +2σ) was advected into northern Maine from the east by the low-level northeasterly flow poleward of the cutoff cyclone (Fig. 5.19). The advection of anomalous PW from the east likely further contributed to the larger precipitation amounts observed Maine, as compared to other regions of the Northeast US. Finally, enhanced precipitation (10–15 mm) was also observed along the Green Mountains and the Berkshires on 2 January 2010 (Fig. 5.12b). Surface observations at 1000 UTC 3 January 2010 show west–northwesterly surface winds throughout the Hudson and Champlain Valleys (Fig. 5.20). The direction of the low-level flow resulted in upslope flow and enhanced precipitation along the western slopes of the Green Mountains and the Berkshires, as indicated by a local maximum in base reflectivity values (15–30 dBZ) in Fig. 5.20. 77 5.2.3 Meteorological Conditions: 3 January 2010 The heaviest precipitation on 3 January 2010 occurred in the 6-h periods following 1200 and 1800 UTC 3 January 2010. Therefore, the focus of this section will be on examining the upper-level, midlevel, and low-level tropospheric conditions at these times to identify the synoptic-scale and mesoscale features that contributed to the light precipitation in New England, western New York, and the Champlain Valley (Fig. 5.12c). At 1200 UTC 3 January 2010 the lobe of cyclonic absolute vorticity at 500 hPa that contributed to precipitation in northern New England on the previous day was nearly out of the region (Fig. 5.21a). This lobe of cyclonic absolute vorticity had weakened over the Atlantic Ocean at 1800 UTC 3 January 2010 and a second lobe of cyclonic absolute vorticity extending westward from the 500-hPa cutoff cyclone center was present over Massachusetts (Fig. 5.21b). Inferred differential cyclonic absolute vorticity advection downstream of this lobe likely supported the precipitation observed throughout New England on 3 January 2010 by contributing to favorable QG forcing for ascent over the region. Persistent advection of warm air into the Northeast US from the north and east at 850 hPa (Fig. 5.22), and thus an inferred maximum in the Laplacian of warm air advection, also contributed to QG forcing for ascent. The precipitation in New England was likely further supported by a quasi-stationary region of 925-hPa frontogenesis associated with the southwestward moving warm front that had stalled over southern New Hampshire (not shown). 78 At the surface, PW values throughout the Northeast US at 1200 UTC 3 January 2010 were less than 12 mm (Fig. 5.23), which likely contributed to the low precipitation observed on this day as they likely did on 1 January 2010. The 850-hPa flow across the Northeast US was north-northwesterly and cold air (below −12°C) was in place over New York (Fig. 5.22), both of which provided favorable conditions for the development of lake-effect snow bands. Radar and surface observations at 1300 UTC 3 January 2010 show a prominent lake-effect precipitation band in upstate New York collocated with low-level northwesterly flow over Lake Ontario (Fig. 5.24). Surface winds at Burlington, VT, were north–northwesterly as compared to light westerly or southwesterly winds in surrounding areas, suggesting that the low-level flow was being channeled through the Champlain Valley. The north–northwesterly winds across Lake Champlain provided favorable conditions for the ongoing support of a lake-effect snow band and contributed to the record-breaking snowfall observed at Burlington, VT. Therefore, the lakes acted as a moisture source, despite low PW values throughout the Northeast US, contributing to the light precipitation observed in western New York and the Champlain Valley on 3 January 2010. 5.2.4 Conceptual Summary Schematic diagrams of the key synoptic-scale features that contributed to the precipitation distributions on 2 and 3 January 2010 in association with the 1–4 January 2010 cutoff cyclone event are presented in Figs. 5.25a,b. On 2 January 2010, precipitation across regions of northern New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire, and 79 throughout Maine, was enhanced by: (1) ascent associated with divergence within the equatorward exit region of an easterly jet streak at upper levels; (2) QG forcing for ascent associated with inferred differential cyclonic vorticity advection west of the 500-hPa cutoff cyclone and an inferred maximum in the Laplacian of warm air advection at 850 hPa; (3) a region of frontogenesis along a southwestward moving warm front; and (4) advection of anomalous PW from the east poleward of the cutoff cyclone (Fig. 5.25a). On 3 January 2010, light precipitation in New England occurred in a region of persistent QG forcing for ascent associated with inferred differential cyclonic vorticity advection and warm air advection, while light precipitation in western New York and the Champlain Valley was attributed to lake-effect precipitation (Fig. 5.25b). On 2 January 2010, the cutoff cyclone would have been placed into the “HP neutral cutoff” composite category. Comparing the schematic diagram for 2 January 2010 (Fig. 5.25a) to the schematic diagram for the “HP neutral cutoff” category (Fig. 4.4c), the synoptic-scale features contributing to precipitation are comparable in that the primary features include: (1) ascent favored within the exit region of an upper-level jet streak; (2) inferred differential cyclonic absolute vorticity advection downstream of a 500-hPa absolute vorticity maxima; (3) enhancement of precipitation along a surface warm front; and (4) advection of anomalous PW into the Northeast US by the low-level flow poleward of the surface cyclone. While the features remain similar, the two schematic diagrams appear to differ by a rotation of approximately 90°. For instance, rather than a southwesterly upper-level jet streak as depicted in the “HP neutral cutoff” schematic, there was an easterly upper-level jet streak poleward of the cutoff cyclone on 2 January 2010. This difference is largely due to the presence of a highly amplified ridge 80 associated with a large-scale blocking pattern and the negative phase of the NAO on 2 January 2010 that acted to increase the geopotential height gradient north and east of the cutoff cyclone and contributed to the development of an easterly jet streak poleward of the cutoff cyclone. The cutoff cyclone on 3 January 2010 would have been placed into the “LP neutral cutoff” composite category. The schematic diagrams for 3 January 2010 (Fig. 5.25b) and the “LP neutral cutoff” composite category (Fig. 4.5c) are similar, with northwesterly low-level flow west of the cutoff cyclone contributing to light precipitation observed in the southwest quadrant of the cutoff cyclone, in association with lake-effect snow bands. The schematic diagrams differ in that there is an upper-level easterly jet and a southwestward-moving warm front that contributed to light precipitation in New England on 3 January 2010, whereas these features are not evident in the composite schematic diagram. 5.3 The 12–16 March 2010 Cutoff Cyclone Event 5.3.1 Event Overview The 12–16 March 2010 cutoff cyclone event was a long duration event, with the cutoff cyclone remaining within the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain for approximately 84 h. The event was associated with widespread flooding throughout southern New England and high winds across New Jersey and southern New York. For instance, at 0000 UTC 14 March 2010 a wind gust of 64 kt (33 m s−1) was recorded at Kennedy 81 International Airport (Grumm 2010). Leading up to the event, NWP models did well forecasting that precipitation would occur; however, the forecast precipitation amounts were much lower than observed and they did not capture the terrain influences well (e.g., Grumm 2010; Stuart 2010b). The 12–16 March 2010 cutoff cyclone developed from a broad trough in place over the central US and entered the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain at 1200 UTC 13 March 2010 (Fig. 5.26). The track of the cutoff cyclone indicates that the cyclone remained south of Pennsylvania as it traveled eastward toward the Atlantic coast. On 15 March 2010, the cutoff cyclone stalled over the Atlantic Ocean and retrograded southeast of New Jersey becoming reabsorbed into the background westerly flow at 0000 UTC 17 March 2010. Extremely heavy precipitation was observed with the 12–16 March 2010 cutoff cyclone event, as indicated by the four-day NPUV QPE (Fig. 5.27). Locations in eastern Massachusetts and coastal New Hampshire received 125–180 mm of precipitation, with a second precipitation maximum (120–160 mm) observed in New Jersey. This cutoff cyclone event was associated with precipitation distributions that varied considerably from one cutoff cyclone day to the next (Figs. 5.28a–d). The heaviest precipitation associated with this cutoff cyclone event occurred on 13 and 14 March 2010. The precipitation distribution for 13 March 2010 indicates that over 25 mm of precipitation was observed throughout coastal regions of the Northeast precipitation domain, while lower precipitation amounts (5–20 mm) were observed throughout the Hudson Valley in eastern New York (Fig. 5.28b). The heaviest precipitation on this day was observed in southern New England and northern New Jersey, with over 100 mm of precipitation. On 82 14 March, over 80 mm of precipitation was observed in northern Massachusetts and coastal New Hampshire, while lighter precipitation (>25 mm) persisted across regions of New Jersey (Fig. 5.28c). The focus of the following sections will be on examining 13 and 14 March 2010 to determine what features contributed to the observed precipitation distributions on these respective days. 5.3.2 Meteorological Conditions: 13 March 2010 The heaviest precipitation on 13 March 2010 occurred in the 6-h periods following 1800 UTC 13 March 2010 and 0000 UTC 14 March 2010. Upper-level, midlevel, and low-level tropospheric conditions at these times will be discussed to identify the synoptic-scale and mesoscale features that contributed to the heavy precipitation in southern New England and northern New Jersey (Fig. 5.28b). At upper levels, an easterly jet greater than 35 m s−1 (68 kt) was forming poleward of the cutoff cyclone at 1800 UTC 13 March 2010 and extended farther west across Pennsylvania by 0000 UTC 14 March 2010 (Figs. 5.29a,b). Divergence was evident within the poleward entrance region of the easterly jet streak over Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and southern New England, which likely contributed to ascent in these regions of observed heavy precipitation. The 250-hPa zonal wind anomaly at 0000 UTC 14 March 2010 exceeded −3σ poleward of the cutoff cyclone (Fig. 5.30), indicating that the cyclone was purely separated from the background westerly flow (e.g., Stuart and Grumm 2004, 2006). 83 At 700 hPa, Q-vector convergence was evident east of the cutoff cyclone (Fig. 5.31), indicative of favorable QG forcing for ascent that likely contributed to the heavy precipitation observed in New Jersey on 13 March 2010. At low levels, a strong (>60 kt) southeasterly jet was in place across the Northeast US (Fig. 5.32), corresponding to zonal wind between −3 and −5σ (not shown). The onshore low-level flow was favorable for advection of moist air from the east, resulting in +1 to +3σ PW values across the Northeast US (Fig. 5.33). The anomalous PW advection into the Northeast US likely further contributed to the heavy precipitation observed in southern New England and New Jersey on 13 March 2010. Despite the widespread heavy precipitation observed on 13 March 2010, there were also regions of suppressed precipitation associated with downslope flow. For example, the Hudson Valley in eastern New York received only 5–15 mm of precipitation, while surrounding areas received greater than 25 mm (Fig. 5.28b). Surface observations at 1800 UTC 13 March 2010 indicate that there were easterly surface winds throughout the Northeast US (Fig. 5.34). The direction of the low-level flow resulted in downslope flow and suppression of precipitation throughout the Hudson Valley in eastern New York, as indicated by a local minimum in base reflectivity values. 5.3.3 Meteorological Conditions: 14 March 2010 The heaviest precipitation on 14 March 2010 occurred in the 6-h periods following 1200 and 1800 UTC 14 March 2010. Hence, the focus of this section will be on examining upper-level, midlevel, and low-level tropospheric conditions at these time 84 periods in order to identify the synoptic-scale and mesoscale features contributing to the heavy precipitation across northern Massachusetts, coastal New Hampshire, and New Jersey (Fig. 5.28c). At upper levels, the easterly jet streak poleward of the cutoff cyclone persisted and divergence within the entrance and exit regions of this jet streak continued to provide favorable conditions for ascent over the region of heaviest precipitation in northern Massachusetts (not shown). At 500 hPa, a lobe of cyclonic absolute vorticity northeast of the cutoff cyclone center was evident at 1200 UTC 14 March 2010 (Fig. 5.35a) and at 1800 UTC this lobe of cyclonic absolute vorticity had moved westward across southern New England and over New Jersey (Fig. 5.35b). In addition, at low levels, southeasterly flow east of the cutoff cyclone resulted in advection of warm air into New England (Fig. 5.36). By application of Eq. 4.1, favorable QG forcing for ascent, associated with inferred differential cyclonic vorticity advection downstream the lobe of 500-hPa cyclonic absolute vorticity and an inferred maximum in the Laplacian of warm air advection at 850 hPa over New England, likely contributed to the precipitation observed. The orientation of the southeasterly low-level jet continued to favor advection of anomalous warm, moist air into the coastal regions, as indicated by the 850-hPa equivalent potential temperature field at 1200 UTC 14 March 2010 (Fig. 5.37). At this time, advection of warm, moist air was maximized [>20 K (3 h)−1] along coastal Massachusetts. The strong equivalent potential temperature advection was collocated with the region of heaviest precipitation observed across northern Massachusetts and coastal New Hampshire on this day. In addition, a region of 925-hPa frontogenesis developed in southern New England at 1200 UTC 14 March 2010 (Fig. 5.38), in 85 association with the equivalent potential temperature advection. This region of frontogenesis remained quasi-stationary over the following 24 h (not shown), likely acting to further enhance precipitation in Massachusetts and coastal New Hampshire. 5.3.4 Conceptual Summary Schematic diagrams of the key synoptic-scale features that contributed to the precipitation distributions on 13 and 14 March 2010 are presented in Figs. 5.39a,b. On 13 March 2010, the heavy precipitation in southern New England was supported by favorable conditions for ascent in association with divergence within the entrance region of an easterly jet streak at upper levels (Fig. 5.39a). Advection of anomalous warm, moist air by a strong southeasterly low-level jet also contributed to the heavy precipitation amounts observed on this day in both southern New England and New Jersey. On 14 March 2010, support for precipitation in northern Massachusetts and coastal New Hampshire was provided by persistent upper-level and low-level jet streaks in addition to a region of frontogenesis that had developed along the coast (Fig. 5.39b). Precipitation in New Jersey on 14 March 2010 was lighter than on 13 March 2010; however, because of the proximity to the midlevel cutoff cyclone center, precipitation continued due to favorable QG forcing for ascent provided by inferred differential cyclonic absolute vorticity advection in the lower troposphere and an inferred maximum in the Laplacian of warm air advection at 850 hPa. Both the 13 and 14 March 2010 cutoff cyclone days would have been placed into the “HP neutral cutoff” composite category. The 13 and 14 March 2010 schematic 86 diagrams (Figs. 5.39a,b) compare well with the “HP neutral cutoff” composite schematic diagram (Fig. 4.4c). Several contributing features to heavy precipitation depicted in the composite schematic diagram were confirmed by the examination of 13 and 14 March 2010: (1) the location of the cutoff cyclone was to the southeast of the Northeast precipitation domain; (2) the heaviest precipitation occurred in the northeast quadrant of the cyclone; (3) forcing for ascent was supported by divergence associated with an upper level jet streak; (4) southeasterly low-level flow advected Atlantic moisture into the region; and (5) a surface warm front acted to locally enhance precipitation. 87 Fig. 5.1. NCEP Global Ensemble Forecast System valid at 1200 UTC 3 February 2009 and initialized at (a,b) 0000 UTC 30 January, (c,d) 1200 UTC 30 January, and (e,f) 1800 UTC 30 January. Left panels show 1008 and 1020 hPa MSLP isobars of each member (hPa, colored contours), the mean of all members (hPa, black contour), and the spread about the mean (hPa, shaded). Right panels show the average MSLP isobars of all members (hPa, green contours) and the standardized anomalies computed from the mean (σ, shaded). (Figure modified from Grumm et al. 2009, Fig. 13.) 88 Fig. 5.2. Mean 500-hPa geopotential height (dam, black contours) for 0000 UTC 3 February–0000 UTC 4 February 2009 and the track of the 500-hPa cutoff cyclone center every 6 h (red contours). The brown bold lines depict the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain. Fig. 5.3. Two-day NPVU QPE (mm, shaded) ending 1200 UTC 4 February 2009. The black bold line depicts the Northeast precipitation domain. 89 Fig. 5.4. 250-hPa geopotential height (dam, black solid contours), wind speed (m s−1, shaded), and divergence (10−5 s−1, red dashed contours) at (a) 1800 UTC 3 February 2009 and (b) 0000 UTC 4 February 2009. Fig. 5.5. 500-hPa geopotential height (dam, black solid contours), absolute vorticity (10−5 s−1, shaded), cyclonic absolute vorticity advection [10−5 s−1 (3 h)−1, blue dashed contours] and wind (kt, barbs) at (a) 1800 UTC 3 February 2009 and (b) 0000 UTC 4 February 2009. 90 Fig. 5.6. 850-hPa geopotential height (dam, black solid contours), temperature (°C, shaded), and wind (>30 kt, barbs) at 1800 UTC 3 February 2009. Fig. 5.7. 700-hPa geopotential height (dam, black solid contours), temperature (°C, green dashed contours), Q vectors (>5 x 10−7 Pa m−1 s−1, arrows), and Q-vector convergence (10−12 Pa m−2 s−1, shaded) at (a) 1800 UTC 3 February 2009 and (b) 0000 UTC 4 February 2009. 91 Fig. 5.8. MSLP (hPa, black solid contours), 1000–500 hPa thickness (m, red dashed contours), and PW (mm, shaded) at 1800 UTC 3 February 2009. Fig. 5.9. Schematic depicting the 500-hPa geopotential height (dam, black contours) at 1800 UTC 3 February 2009 and key synoptic-scale features that contribute to precipitation for the 2–3 February 2009 cutoff cyclone event. The brown bold line depicts the Northeast precipitation domain. 92 Fig. 5.10. Mean 500-hPa geopotential height (dam, black contours) for 0000 UTC 2 January–1200 UTC 4 January 2010 and the track of the 500-hPa cutoff cyclone center every 6 h (red contours). The brown bold lines depict the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain. Fig. 5.11. Four-day NPVU QPE (mm, shaded) ending 1200 UTC 5 January 2010. The black bold line depicts the Northeast precipitation domain. 93 Fig. 5.12. 24-h NPVU QPE (mm, shaded) ending (a) 1200 UTC 2 January 2010, (b) 1200 UTC 3 January 2010, (c) 1200 UTC 4 January 2010, and (d) 1200 UTC 5 January 2010. The black bold line depicts the Northeast precipitation domain. Fig. 5.13. As in Fig. 5.4 except at (a) 0000 UTC 3 January 2010 and (b) 0600 UTC 3 January 2010. 94 Fig. 5.14. 250-hPa geopotential height (dam, black contours) and standardized anomalies of 250-hPa zonal wind (σ, shaded) at 0000 UTC 3 January 2010. Fig. 5.15. As in Fig. 5.5 except at (a) 0000 UTC 3 January 2010 and (b) 0600 UTC 3 January 2010. 95 Fig. 5.16. As in Fig. 5.6 except at 0000 UTC 3 January 2010. Fig. 5.17. 700-hPa geopotential height (dam, black solid contours), temperature (°C, green dashed contours), Q vectors (>5 x 10−7 Pa m−1 s−1, arrows), and Q-vector convergence (10−12 Pa m−2 s−1, shaded) at (a) 0000 UTC 3 January 2010 and (b) 0600 UTC 3 January 2010. 96 Fig. 5.18. 925-hPa frontogenesis [K (100 km)−1 (3 h)−1, shaded], potential temperature (K, black solid contours), and wind (kt, barbs) at (a) 0000 UTC 3 January 2010 and (b) 0600 UTC 3 January 2010; (c) cross section of 925-hPa frontogenesis [K (100 km)−1 (3 h)−1, shaded], potential temperature (K, black solid contours), and omega (μb s−1, dashed contours; upward is indicated in red, downward is indicated in blue) at 0600 UTC 3 January 2010. The blue dashed line in (b) indicates the approximate location of the cross section in (c). 97 Fig. 5.19. 850-hPa geopotential height (dam, black solid contours), wind (kt, barbs), PW (mm, red dashed contours), and standardized anomalies of PW (σ, shaded) at 0000 UTC 3 January 2010. Fig. 5.20. Base reflectivity (dBZ) and surface observations at 1000 UTC 3 January 2010. 98 Fig. 5.21. As in Fig. 5.5 except at (a) 1200 UTC 3 January 2010 and (b) 1800 UTC 3 January 2010. Fig. 5.22. As in Fig. 5.6 except at 1200 UTC 3 January 2010. 99 Fig. 5.23. As in Fig. 5.7 except at 1200 UTC 3 January 2010. Fig. 5.24. As in Fig. 5.19 except at 1300 UTC 3 January 2010. 100 Fig. 5.25. As in Fig. 5.8 except for (a) 2 January 2010 and (b) 3 January 2010. 101 Fig. 5.26. Mean 500-hPa geopotential height (dam, black contours) for 0600 UTC 13 March–1800 UTC 16 March 2010 and the track of the 500-hPa cutoff cyclone center every 6 h (red contours). The brown bold lines depict the Northeast cutoff cyclone domain. Fig. 5.27. Four-day NPVU QPE (mm, shaded) ending 1200 UTC 16 March 2010. The black bold line depicts the Northeast precipitation domain. 102 Fig. 5.28. 24-h NPVU QPE (mm, shaded) ending (a) 1200 UTC 13 March 2010, (b) 1200 UTC 14 March 2010, (c) 1200 UTC 15 March 2010, and (d) 1200 UTC 16 March 2010. The black bold line depicts the Northeast precipitation domain. Fig. 5.29. As in Fig. 5.4 except at (a) 1800 UTC 13 March 2010 and (b) 0000 UTC 14 March 2010. 103 Fig. 5.30. At in Fig. 5.13 except at 0000 UTC 14 March 2010. Fig. 5.31. As in Fig. 5.16 except at 0000 UTC 14 March 2010. 104 Fig. 5.32. 850-hPa geopotential height (dam, black contours), wind speed (m s–1, shaded), and wind (kt, barbs) at 0000 UTC 14 March 2010. Fig. 5.33. As in Fig. 5.18 except at 0000 UTC 14 March 2010. 105 Fig. 5.34. As in Fig. 5.19 except at 1800 UTC 13 March 2010. Fig. 5.35. As in Fig. 5.5 except at (a) 1200 UTC 14 March 2010 and (b) 1800 UTC 14 March 2010. 106 Fig. 5.36. As in Fig. 5.6 except at 1200 UTC 14 March 2010. Fig. 5.37. 850-hPa equivalent potential temperature (K, black contours), equivalent potential temperature advection [K (3 h)−1, shaded], and wind (m s–1, barbs) at 1200 UTC 14 March 2010. 107 Fig. 5.38. As in Fig. 5.17a except at 1200 UTC 14 March 2010. 108 Fig. 5.39. As in Fig. 5.8 except for (a) 13 March 2010 and (b) 14 March 2010. 109