Development of a supportive learning environment

advertisement

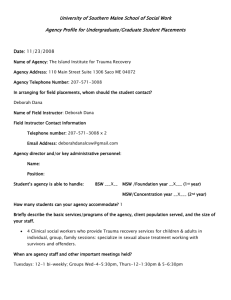

Feet under the table: Students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of learning support provided during their first year of study on health and social care programmes Steve May, BEng, MSc, Cert. Ed. Senior Researcher, Kingston University E-mail: s.may@kingston.ac.uk David Hodgson, BA (Hons), MA, LLM Principal Lecturer and Faculty Teaching and Learning Strategy Coordinator, Kingston University Di Marks-Maran, BSc, MA Visiting Professor of Nursing Kingston University Paper presented at the Society for Research into Higher Education Conference, University of Edinburgh, 13-15 December 2005 1 Abstract This paper shows how research projects undertaken at Kingston University have impacted on university policy related to student support in a widening participation agenda, and the student support practices of one faculty within that university. As part of the move to integrate the university's learning and teaching strategy with its widening participation strategy a number of funded projects have been undertaken. These projects have, in turn, influenced university widening participation and learning and teaching policies. The focus of this paper is on three such projects (which are related to each other): the University Retention Project, the Study Skills Weekends project and the Supportive Learning Environment Project (undertaken within the Faculty of Health and Social Care Sciences). For each, a case study approach was used, influenced by a Realistic Evaluation framework (Pawson & Tilley 1997). The paper explores how the University Retention Project has impacted on the widening participation agenda at Kingston University and on how the Health and Social Care Sciences faculty has addressed, and is addressing, the student support issues that arose from the study through follow -up projects, in particular - the Faculty Supportive Learning Environment Project (SLEP). This is an action research project that brought together students, academic staff and practice colleagues in the fields of health care and social work. Using focus group methodology, a rich picture has emerged of the issues within a supportive learning environment and the practices that lead to such an environment for the faculty, especially in year 1. Three project groups have been established to initiate innovations that emerged from this data in health and social care student support. Each project group is made up of students, academic staff and colleagues from health and social care practice. As well as leading the implementation of each innovation, the groups designed each project to include an evaluative research component. This paper presents the current state of the SLE project and the findings and issues that are emerging for the faculty. 2 Introduction Kingston University has a strong widening participating (WP) ethos, but there is a recognition in policy of two realities: firstly, that enabling students from non-traditional backgrounds to succeed at university raises important issues and consequences at different stages in the student life cycle (HEFCE 2001); secondly that widening access has implications for the learning experience of all students. Figure 1 highlights the different stages in which learning support may be available to students (prior to entry, during induction, through the first year , during subsequent years and while embarking on a postuniversity career). Figure 1 Student Life Cycle (adapted from HEFCE 2001) 1. Aspiration raising 6. Employment 2. Pre-entry advice and guidance 5. Easing progression through the programme 3. Admissions 4. First year experience Alongside university-wide WP initiatives, each Faculty at Kingston University has engaged in local projects to address challenges of widening participation at different stages of the student life cycle. This paper presents a case study of how one faculty, the Faculty of Health and Social Care Sciences utilised findings from university-wide research on student retention and withdrawal and developed a series of projects responsive to the ongoing evaluation student experiences. The faculty-based initiatives began with the formation of the Initial Learning Experiences Group, a cross-faculty forum for information sharing and project development. The Group initiated the Pre-Entry Study Skills Weekends Project, focusing on pre-entry learning support and monitored school-based work to improve the experiences of first year undergraduate students. The Supportive Learning Environment Project (SLEP) is a ground-up action research project designed to draw together the 3 perspectives of students, university staff and professional practice colleagues to inform projects designed to improve student experience within and beyond the first year, including practice placements. The relationship between these elements is illustrated in Figure 2. The diagram highlights the chronological development of student support initiatives in tune with the student life cycle. The foregoing account describes a sequential and layered approach to the attempt to understand and respond to student experience. A brief description is given of the aims, methodology and key findings of each project. This is followed by a discussion of the issues and the consequences of widening participation in Health and Social Care programmes. 4 Figure 2 :Iterative Processes of Practice Development through Realistic Evaluation Faculty Initial Learning Experiences Group (ILEG) Kingston University Student Retention Research Project Faculty-wide PreEntry Study Skills Weekends Project and Evaluation School-based First Year Experience Initiatives Supportive Learning Environment Initiative Incorporating Faculty data from KU Retention Project and Faculty Study Skills Project Evaluating School-based First Year Experience Initiatives Evaluating student experience beyond Year One Consulting with academic and professional staff Devising Projects with Evaluative Components Spreading the Learning Team (peer support) Model Template for Placement Induction & Support / incentives for mentors Review of Academic Tutor Role and good practice guide 5 University retention project The University-wide retention project used both quantitative and qualitative data to begin to probe the reasons for withdrawal at first year undergraduate level. The study was designed to inform wider University strategies and developing policies on, for example, widening participation, learning and teaching, human resource development strategy and student services. On a micro level the study aimed to inform and support faculty based retention projects and other teaching, learning and assessment development initiatives. Previous studies of retention issues highlighted the significant of factors associated with both previous and current learning experiences. In a major study on the issue of retention in six higher education institutions in the North West (Yorke, 2000), respondents cited quality of teaching on the programme as a significant factor. There was also a perception amongst respondents that they had received inadequate staff support outside the timetabled hours of the programme and that there had been a lack of personal support from staff; points mirrored in the Kingston Retention study. Mackie, (2001) investigated the experience of students in the first year of an undergraduate degree in a faculty of business in a new University. The author notes that it was not the case that one factor precipitated withdrawal, rather, different forces may interact with one another in ways which lead some students to feel that they cannot continue, whereas, for other students, the problems they encounter can become a ‘spur’ to their determination to progress on the course. The importance of the quality of the first year experience is, perhaps, particularly strong for those students who come from families in lower socio-economic groups where there may be little experience of higher education. A study by Connor et. al. (2001) notes that students from lower social class groups enter higher education with different expectations than those from higher social class groups and that students from lower social class backgrounds were less confident that they would be able to cope with academic pressures and workload; gaining the entry qualifications and the application process itself. (Hall et. al. 2001) concludes that the first semester is a crucial time for non traditional students and that there are key factors, during this initial period of the course, which can inhibit progression in particular low self esteem amongst students about their academic capability, fear of the learning process and isolation from other students. Methodology The first stage of the Kingston Retention Project involved interviewing staff, recording their perspectives and gathering admissions data and university records to identify profiles of students (by age, gender, social class, ethnicity, admissions route, distance from home, distance from term time accommodation, main entry qualification, faculty and date of withdrawal). In addition those who had withdrawn were telephoned and asked the reasons for their withdrawal through a questionnaire, while data on the first year experience of retained student was gathered from focus groups discussions with samples from each faculty. The quantitative and qualitative data collected from withdrawn students was processed through a purpose designed database along with the university records to allow detailed analysis of issues and links between issues. Themes arising from the focus group discussions could then be analysed in the context of the combinations of reasons for 6 withdrawal given by pockets of vulnerable students to give a rich picture of why some students choose to leave the University. Findings The key findings from the university wide study were: Unmet expectations is the prime reason given by student for withdrawal from the university Mature students were more likely to cite financial problems as a reason for withdrawal. Students admitted through UCAS clearing were more dissatisfied over the range of issues than were standard entrants in the first semester, particularly in regard to expectations not being met, and organisation of the course. Class size is problematic for many students not used to very large groups although the quality of teaching was thought generally good by retained students and not much cited by those who had left. Friendships and peer support were extremely important for new students. The way in which they are grouped in tutorials, seminars, to give presentations etc, play an important part in the first year experience. Both withdrawn and retained students were highly critical of a lack of course related information and timetable changes. Those who travel a long distance have part-time work or other commitments or who have made a significant investment in coming to university expected high quality provision and particularly resented what they saw as poor organisation. Academic support through good quality feedback was greatly valued by students as a way to encourage and enhance learning. Many have less contact with tutors than they may have been used to, making written feedback all the more important. Students saw feedback it as an important way to learn and appreciated assessment feedback but noted that the amount given was extremely variable between lectures. In the Faculty of Health and Social Care Sciences focus groups were carried out with students on DipHe Nursing and BA Social work courses. Details of the main findings from these groups elaborate on some of the themes listed above. Induction and the start of the course Students liked being put into small groups so that they could get to know one another. Nursing students reported: “Initially it started off very well, we were sort of very gently eased into university life” However social work students commented about replication of Summer Schools that they had already attended and that the transition from induction to the course proper was problematic: 7 "I did the summer school and then I had to repeat everything in Induction week, that was really frustrating" "You kind of make relationships in the induction week, but then they were split apart by the introduction of learning teams, then you had to re-establish." Support from staff Nursing students found access to their personal tutors a problem but it seemed to depend a lot on the tutor. They suggested time-tabled sessions to guarantee access. They realise that tutors have a heavy workload and feel that they could help each other if they could get together into groups to discuss assignments. “…….and then we had terrible trouble finding our tutor after that and I think that being so new to it and perhaps not understanding or knowing the level of work that might be expected in the first assignment, we had trouble finding, locating, knowing exactly what guidance (was available)” “It does put pressure on tutors to have to see us as individuals, that’s why I think it’s better if we can work together in student groups and sort of help each other”. The Social Work students reported similar issues: "The tutorial was so obviously a token effort. It was like ‘Well we have to give a tutorial so lets just get everyone in for half an hour, give them a tutorial and forget about it for the rest of the course.’ It feels like you sink or swim." Peer Support and friendships This was very important to both groups of students and they appreciated being split into small groups at the start of the course. "Without each other I think there would have been times when there would have been a lot more of us more of us would have left." Issues connected with Class size The Nursing students felt that learning was impeded by very large class sizes which were usually a new experience. While they appreciated that having such class sizes may be largely unavoidable for certain purposes, some had problems with note-taking, teaching methods and attendance monitoring. “The lecturers try to provoke dialogue which is totally ludicrous because the first three people in the front row have a dialogue with the lecturer. For the rest of the lecture everyone’s talking because they can’t hear what’s going on and they’re bored” Students found that disruption by other students, particularly in the lectures, inhibit learning. They appreciated that efforts were being made to address this. “It’s a dual responsibility and that’s where I think there are some good student guidelines that have been laid down saying OK the student is expected to behave in such a way and the lecturer is expected to behave in such a way” 8 Course Organisation Nursing students were frustrated by apparent lack of communication between lecturers and provision of reliable information to students. “..you have one lecturer who says I don’t know if you’ve covered this before –Yes we have covered it before but we don’t know what you’re going to tell us! Could you speak to the other lecturer and actually compare lecture notes” Social Work also students identified organisational issues "…I just think it's so badly organised. Because we are mature students we expect a certain standard for the amount of money you pay and I don't think what they're providing is good enough." Learning on placement Both Nursing and Social Work students said they found placements to be a good learning and networking experience although this varied depending particularly on the mentor. “Going out on placement is good. If you’re put on a ward with someone else you might not have spoken to them before, you do have quite an intensive period of being able to meet new people”. However the nursing students in particular felt that there was a lack of communication between practice professionals and university staff. “I’ve turned up and people haven’t known who I am, whether I was going to be there” Pre-Entry Study Skills Weekends The impetus for establishing a study skills weekend prior to entry into health and social care programmes arose from the Faculty’s Initial Learning Experiences Group (ILEG) whose remit was to develop improvements in the pre-entry and early university experience for health and social care students. Originally run as a weekend programme for students prior to commencing their university programmes, the two day event aimed to increase awareness, prior to starting at university, of study skills and more general strategies for managing learning in higher education. The project included an ongoing evaluation, the purpose of which was to add to the body of evidence as well as to inform future decision-making about provision of pre-entry study skills courses. The objectives of the evaluation were: To follow up and seek the views of students who attended the study skills weekends To follow up those students who did not attend the study skills weekends and identify how they prepared for the first year experience To ascertain from personal tutors of first year students the level of student preparedness for the first year experience with them 9 To identify how future pre-entry support can be developed to help students to better prepare for their university experience The concept of pre-entry learning is embraced within HEFCE’s notion of the student life cycle (HEFCE 2001) which includes two important stages: aspiration raising and pre-entry support and guidance. The project and accompanying evaluation aimed to test the hypothesis that the provision of pre-entry workshops related to study skills and coping strategies would positively impact on the first year experience and would increase student retention. From a Faculty perspective, the entry gate had already been widened, partly in response to health and social care workforce pressures. Thus, recruitment practices departed from the higher education tradition to recruit those regarded as most able to cope as independent learners. . Nearly all Higher Education Institutions provide some form of pre-entry support for students, dedicating up to 34% of this support through summer schools and courses that include study skills (University of Bradford 2002). The range in the structure and content of these courses is varied and extensive and the “discipline specific” approach is favoured (Durkin & Main 2002). Methodology The study skills programme included more than introduction of certain learning and study skills including maths, writing skills and basis health-related science concepts. It also offered pre-entry students an opportunity to orientate to the campus and to meet with “student ambassadors” – existing students who had completed their first year of study. Measuring the effectiveness of the study skills weekends in relation to quantitative measures of retention posed methodological challenges that have been reported elsewhere (Tysome 2003). A qualitative approach to evaluation was chosen, using focus group discussions and semi structured interviews, alongside formal student evaluation forms. Findings The evaluation highlighted a range of issues associated with expectation and anticipation, affirmation and confidence, confirmation of choice and enhancement of commitment. All of these issues were accompanied by varying degrees of anxiety about the impending experience of university life. The main theme arising from the participant’s views on the weekends was anticipation frequently linked to confirmation that the decision they had made to enrol at the university was right for them to commit to three years of study. Reasons for attending the study skills weekend were varied but the majority indicated that they came to orientate to the university and its environment and meet other students and lecturers. “I’d never faced 200 people before and I thought it would be a good exercise, as well as to get to know the university, but primarily to meet people, to see some people, to recognise some people.” 10 “I hadn’t made a decision to come to university and I was wavering between whether to come or not, I would have made that decision based on the two study skills days. I would have made the decision then if I was wavering…” For those not attending the study skills weekend a range of reasons were cited including childcare, other domestic or work-related reasons. Some stated they that had never received information about the events or had applied but were told the sessions were full. Some chose not to attend as they were confident that they would learn all they needed to learn on course “My attitude was everything I need to know to be a good midwife I will be learning in the next three years and I am going to learn it step by step…” Anticipation related to what the participants were expecting when they finally commenced the programmes they had been recruited to, they were able to evaluate their experience of the weekend in a positive light in meeting their expectations of the course. Level of confidence in the light of previous experience emerged as dominant theme “Maybe peace of mind that you can complete the course and do everything, rather than worrying that you can’t” The notion of confidence was associated with age of the participant. The following quote is indicative of many sentiments expressed by older students: “I’ve left school a long, long time ago, you know, nearly 20 years, so it was a bit of a big thing for me to come to university anyway and knowing that seeing people older than me, I’m not the oldest, seeing people older as well made me a bit more confident.” The value of the weekends was measured in terms of decreasing anxiety or feeling a sense of belonging to the university. By listening to contributions from current first year students they were more reassured about the reality of university life. “We were told about the workload. We were told that it won’t be more than college…But when the guy showed us around he said at some point there is loads. At some point there is nothing and sometimes you cannot balance it out. Sometimes you can’t type the thing because it all comes at once and it has to be in on the same day, and sometimes you can scatter it around and do bits when you haven’t got much to do. It’s just knowing things like that and being prepared in your mind.” Some neutral or negative effects of the study skills weekends were also voiced. “I was quite worried about whether I would be OK with the science aspect of the course and there wasn’t particularly anybody that could reassure me with that…” Lecturers who staffed the weekends had described a tendency among attendees to express increasing anxiety as the weekend progressed. This was characterised in discussions as the “Oh my God” phenomenon with reference to specific academic skills “Well, I went away from that realising I needed to really have a good think about my maths and so in got someone to go through a lot of it with me, but I did find that the teacher went a little bit too fast and I felt a bit panicky.” 11 It was concluded that there was some evidence of anxiety from attending the study skills weekend, although participants also emphasised that they experienced reassurance from meeting the peer group on the weekends. “I’m still always thinking to myself, do I really deserve to be here you know? Am I taking up someone else’s place? Can I, if they have got so much faith in me, can I give that back to them as well?” Students said that the study skills weekends did not prepare them for the real experience of practice placements. This was particularly an issue for nursing and midwifery students who begin practice placements early in their first year. These participants said that they would have valued more opportunity during the study skills weekends to discuss these issues with the first year students in attendance. Questions such as travel to and from placements, organising childcare and managing shift working were overlooked or there had not been enough time to explore them. Faculty initiatives to aid on-course support and guidance for students Alongside the cross-faculty study skills initiative, a range of developments within individual schools were pursue in response to the findings of the Retention Project. Some of these are summarised below in order to illustrate the variety of response regarded as appropriate to local circumstances. Midwifery and Nursing A specialist lecturer now from FE sector was brought in to enhance bridging support on study and academic writing skills identified through formative assessment (in additional to the usual mechanisms, e.g. personal tutors, module leaders, cohort leaders, mentors and clinical liaison lecturers). Nursing The way in which students are inducted has been reviewed redesigned to emphasise small group work rather than large group plenary events Small group work is being used on the Common Foundation Programme (based on different branches / specialisms) to promote group identity and support. Extended inductions are now given for practice placements and liaison lecturers provide regular surgeries in clinical placement areas. Physiotherapy Further development and initial evaluation of group-based peer-assisted learning programme is underway to address increased student group size, address critical thinking skills and promote collaborative approach to learning. The introduction of Peer Learning in the Clinical Setting - each 1st year student is placed with a 3rd year student for half day visits for clinical orientation. Radiography Introduction and review of ‘ice-breaking’ sessions to stimulate student social interaction during induction 12 Increased tutor access and development of Blackboard (VLE) use for individual and small group support Social Work Learning Teams – The learning contract format has been revised with a new emphasis on continuity of tutor group and personal tutor throughout UG studies. A Social work Student Academic Mentors (SSAMs) scheme is now part of mainstream provision following successful pilot scheme. (The scheme is based on US Model, 2 nd & 3rd year students trained and supported to provide academic assistance to 1 st year students – including induction activities, one-to-one email and personal advice and support for groupbased assignment preparation. The personal tutor support in year one has been intensified with the tutor retained throughout the course and fulfilling a parallel role in relation to practice placement Supportive Learning Environment Project The Faculty Supportive Learning Environment Project focussed specifically on what students perceive to be a supportive learning environment in year 1 and beyond. Commencing in early 2004 it aims were to define what is regarded as “supportive” from students’ perspectives, to identify specific measures currently in place that are perceived to be supportive to students and to identify what additional provision would enhance support during year 1 and beyond. This focus on the broader learning environment in supporting students and ways in which this differs across student groups and settings has been reported elsewhere (Packham & Miller, 2000; Dix & Hughes, 2004). Laing & Robinson (2003) concluded from their ethnographic study that consideration must be given to discovering the underlying characteristics of the teaching and learning environment while MacDonald & Stratta (2001) argue that while teachers in higher education focussed on helping non-traditional students adjust to existing higher education ways of working, what is needed is a radical rethink of how we approach a more diverse student population. Gidman (2001), explored literature on the role of the personal tutor in enabling nursing students to achieve and concluded that was no consensus as to the most appropriate system of providing this support. She also highlighted the need for further research studies in this area. Clarke et al (2003) in their study of the impact of Practice Placement Facilitators (PPF), found that students benefited from continuity of support on practice placements and that practice staff derive benefits from an enhanced understanding of the needs of learners through the work of the PPF. The ways in which teaching methods influence the learning environment has also been explored, for example, by Entwistle (2000), who found that didactic lecture styles can encourage surface approaches to learning. Rhodes & Nevill (2004) found that both teaching methods and the friendliness of teaching and non-teaching staff affected student satisfaction and their propensity to withdraw. Trotter & Cove (2005) found that mature and younger students on healthcare programmes had differing learning and teaching requirements, they concluded that as universities widen participation they need to adopt teaching strategies that are suitable for those who are less familiar with traditional models of university teaching, in addition to catering for entrants from school. 13 Methodology Phase 1 of the project involved a forum day in June 2004 for students on health and social care programmes within the Faculty and a second day, in October 2004, for both students and academic staff from the Faculty. Phase 2 commenced in early 2005 and entails identifying and undertaking specific project ideas related to increasing student support. These projects were identified from phase 1. Phase 3 is an ongoing and overarching evaluative research component. Figure 3 shows the structure of the Supportive Learning Environment Project and the aims/activities within it. 14 Figure 3 WP Student Support Project 2004-5 Phase 1 Phase 3 Student Forum Event 1) to report on outcomes & findings from current work on students initial learning experiences; 2) to enable students representatives across Faculty programmes to share experiences related to support for learning 3) to devise an agenda & priorities for action on learning support (programme and Faculty levels) that can inform the second (staff and student) meeting Staff & Student Event 1) To provide a forum for key staff across the Faculty, staff involved in provision of placements in agencies and students to consider messages emerging from research & evaluation of student support. 2) To identify areas for project work on student support (including further research & evaluation) Phase 2 Implement Project Proposals 1. Spreading the Learning Team Model 2a. Template for Placement Induction Programmes 2b. Incentives for Mentors and Good Practice in Placement Supervision 3a. Faculty Audit of Tutor Role 3b. Building Relationships Early Research & Evaluation Components Co-ordinating and summarising messages from existing data sets Constructing framework for consultation with student groups Implementing Consultation (s) Devising further research (in areas lacking reliable data) & evaluation (of development project work) 15 The student forum event consisted of a series of focus groups each led by two facilitators with second and third year students from the Nursing, Social Work and Physiotherapy schools. The aim was to encourage as open a discussion as possible to get a real sense of what it was that contributed to or detracted from a positive environment for learning. They were tape recorded and field notes taken during the sessions. The second event in October was a consultation and planning day for students, University staff and staff from placement agencies. The aims of this day were to provide a forum for key staff across the Faculty, those involved in provision of placements in agencies and students to consider messages emerging from the research & evaluation of student support, and to identify areas for project work on supported learning environments for students (including further research & evaluation). Mixed student/staff discussion groups were formed and each group discussed the following topics: Things I/we do that contribute to a supportive environment for learning (at the University, on placement, connecting the university and placement areas) Things I/we would like to do that would add to a supportive learning environment (at university, on placements, connecting the University and placement areas) In evaluating the project the team was mindful that they were not merely seeking to answer the questions “What worked?” or “Did it work?” Instead, they aimed to uncover what worked for whom and in what circumstances. To this end the data collection and analysis were influenced by the methodology of Realistic Evaluation (Pawson & Tilley 1997) as shown in Figure 4 below. 16 Figure 4 The framework for evaluation of the student learning Environment project (modified from Pawson & Tilley 1997) Identifying the contexts, processes and outcomes related to a supportive student learning environment Conclusions made about what within student learning environment worked for whom and in what circumstances Hypothesising what within the student learning environment might work and in what circumstances Collecting and analysing data about the context, processes and outcomes of a supportive student learning environment (i.e., data about what worked for whom and in what circumstances) 17 The projects presented here were undertaken to test the hypothesis (in realistic evaluation terms) that students from a range of backgrounds might stay and succeed at university if we better understood their expectations, needs and concerns, adjusting our teaching and learning support accordingly. The University Retention Project enabled us to begin to identify these expectations, issues and needs while the Supportive Learning Environment Project is helping us to test the above hypothesis through “realistic cumulation” (Pawson & Tilley 1997, p. 117). Findings The data from the student focus groups were thematically analysed, giving rise to four recurring themes: Academic input and support – enthusiastic lecturers, consistency in the provision of tutorial support and effective communication between lecturers were sub-themes. In addition, the types of teaching methods used by lecturers influenced student perceptions of the learning environment. “The lecture, if they’re passionate or motivated or actually enjoy what they’re teaching and their delivery of that has a massive impact on your learning”. “At the back of the lecture theatre you always see a row of people sleeping and listening to Walkmans. What’s the point in that?” “We have personal tutors but it’s a case of ‘hunt them down’ I think personal tutors shouldn’t be people who are head of anything because they haven’t got time” “She’s (personal tutor) been an absolute godsend because I had a nightmare of a time and she was there to help me out”. Feeling respected – students need to feel respected by, and important to, academic staff and that lecturers make support available in an organised way “This is my second year and the University was all new to me you know… and assignments, exams we don’t get much input from say your personal tutor because there is no one to turn to”. “When I was in the branch environment I found that a lot better. The small group environment works really well….They can see when you’re not understanding something. You feel comfortable to ask questions”. “Lack of communications amongst lecturers and people who are providing the timetable is a big issue as well. You can be waiting half an hour for a lecture. Even though timetable has been up for months they come and say “No-one told us”. Them strolling in half an hour late and then rushing through a lesson. That’s not a positive learning environment”. The physical environment – including space to socialise, access to computers, provision of the University bus to get from campus to campus, suitable teaching rooms. 18 “The room changes at the last moment….The room, the temperature of the room and the seating….You’re freezing and shivering.” “Because rooms are cold students are always going out to the toilet and that causes distractions and because of distraction lessons are all up the creek”. “When I first started, knowing that there was a bus - that was really positive”. Peer support – including the Social Work Student Academic Mentor Scheme (SSAMS) which is a student to student mentoring scheme for students on social work programmes; the University Peer Assisted Learning Scheme (PAL) and the Faculty’s Study Skills weekends for prospective students. “In social work you have a learning contract and individual meeting with your tutor which is compulsory. My experience of that has been pretty positive but I haven’t felt the need to go back to my tutor since then but I think that’s a spin off of the fact that we have learning teams, we have workshop groups, we have seminar groups where you’re working with other people”. “On the Social work course SSAMS students came and interacted and talked to us and that was really useful. And that helps with a positive learning environment, the fact that the first years and the second years are connected”. “Now it’s really positive for me - a mentor (SSAMS)...Having to go back and think about the first year again. And seeing third years -, that people do make it”. The focus groups also explored specific issues related to the nature of academic support that students had experienced. The overall picture that emerged was that although personal and academic tutors were perceived by students to perform a vital function there were large differences in the quality of this support from the student’s experiences. They were generally unaware of the different systems of support provided by the schools within the Faculty. In these focus groups the general consensus was that the Social Work students seem to have the most effective support but that the numbers of students in some other schools made it necessary for them to use different systems for providing support. Focus group discussions also examined student experiences of support and learning on practice placements and how this compared with, and linked to, their experiences in the University. Data from these focus groups show two emerging themes: The role of the mentor - The keys to a positive learning environment on placement were having a good practice placement supervisor/mentor and being accepted and respected by the placement staff team. “I think it’s really important that you feel confident to go to any member of that team and say “Look I need a hand” or “Can I watch what you’re doing?” “I think to be respected; I think that’s a really big issue”. “One who is prepared to supervise you and check that a task is done. A good mentor is student friendly, interested in your learning, wanting to help you through”. 19 “They need to provide you with specific learning opportunities, not just telling you to get on with it.” Communication between academic and placement staff – There were thought to be insufficiently close links between University staff and placement staff. The key factor here was perceived to be communication between the two sets of staff and students. “I’m in my 4th week of my placement and we didn’t get the placement details until the day before we left university although the placement people knew we were coming weeks in advance”. “You get there and they haven’t even sorted your shifts out In summary, the message from all focus groups on the student forum day was about the relationship between communication and support for learning. This included communication between students (for peer support), between Faculty and students (to ensure consistency, appropriateness and timing of information to students), between Faculty staff and placement staff (to enable high quality mentoring) and between staff and students (to bring about a greater degree of mutual respect). (findings from Staff groups) The Staff forum resulted in the emergence of four main themes: Improving student – student interaction Improving student – lecturer interaction Improving student – practitioner/mentor interaction Developing the tripartite relationship between students, the Faculty and the practice placement organisations These four broad themes have led to the establishment of project groups (Phase 2 of the project) made up of students, lecturers and practice staff who are developing specific projects within the above themes. Outlines of these are given below. Student to student (peer) support The Adaptation and extension to other Faculty programmes of the successful ‘Learning Team’ model of peer support developed in the undergraduate programme in the School of Social Work. The project will involve further evaluation of the model and pilot implementation of this model in one other programme, probably the School of Nursing. Tutor to student support This project derives from the variation in student expectations as to the role of personal tutors and will begin with a survey of procedures and practice in different programmes. Alongside data from programme handbooks, data will be collected from staff and students about the operation of the personal tutor system. A report highlighting features of current practice and areas requiring further attention will provide a basis for recommendations on practices to be adopted across the faculty. 20 Tutor - Practitioner - Student support A third area of variation identified in consultations with staff, students and representatives from professional practice agencies was the level and type of support on placements. Placement induction was identified as a key issue, leading to a specific proposal for the creation of a cross-Faculty template for Student Induction Packs. The general template will provide a mechanism to implement common practices in the communication of important information between university tutors, students and practitioners about specific roles, expectations, agency protocols, details of programme requirements etc. The evaluation of these projects will add to our understanding of, and practices related to, providing a supportive learning environment for health and social care students. 21 Discussion Through identifying factors that tend to increase the likelihood of student withdrawal and issues that add to or detract from a supportive learning environment combined with an evaluation of a project designed to address some of the issues and descriptions of other ongoing initiatives this report represents a transferable case study with potential to inform policy at University and faculty levels. Widening participation in health care involves more than increasing the numbers of traditionally under-represented groups in universities. It is also about ensuring that they are retained, and that they succeed and progress (Parry 2003). Through an understanding of what works for whom and in what circumstances, we will be able to provide specific targeted learning support at these crucial times as Laing & Robinson (2003) state “A more appropriate model of non-completion must give greater attention to the underlying nature of an institution’s teaching and learning environment, the manner in which this environment influences student non-completion and the student perceptions and expectations that are generated by this environment”. Our research indicates that a number of factors influence health and social care students in their decisions to remain or to leave the course including expectations not being met, peer support, the quality of teaching and their induction into the programme, which was seen to be a positive experience in our case. The link with retention and the quality and nature of the induction period in the first two weeks at university has also been highlighted elsewhere (Trotter & Cove 2005, Tinto 1987; Parmar & Trotter 2005, May & Bousted 2004) The evaluation of the Study Skills Weekends provided evidence in relation to one way of ensuring that students start the course with realistic expectations and helped to unpack some of the underlying issues. Analysis of the data suggests that students need to overcome anxiety in the experience of newness. The tension between self-confidence and self-doubt in some of the students becomes apparent when they question their right to be in university. Participants highlighted the theme of “confidence” that was manifest in a number of sub-headings. As Tysome (2003, p 6) points out “confidence as a key part of the study skills package is a common theme, whatever the academic ability of the student.” There seems to be a relationship between values or belief systems and their level of confidence of the students. Some had completed university courses in other subjects before applying to health-related programmes, others had started a university degree in other subjects but changed to a more vocational health or social care programme. Some students had dependents and many had made personal sacrifices to enter their chosen health programme. It was apparent that the issue of confidence was in part related to perceptions of academic ability and in part associated with career changes and risk. By attending the study skills weekend’s participants were seeking confirmation and affirmation of the decision to commit to the university and career. The point made by students that the Study Skills weekends did not give preparation for the clinical placement and the finding that a supportive learning environment in practice placements, or lack of one, influences students’ experiences, is borne out in other studies. For example, Van Rhyn & Gontsana (2004) found that students on placement in psychiatric settings experienced high levels of stress the sources for which included, ineffective teaching and learning programmes, poor managerial governance of the service, detachment of professional nurses from their teaching role and poor relationships among 22 staff. This indicates the need for a student introduction to practice placements and for supportive learning environment in practice placements to include provision of effective teaching programmes in practice placements, good management of placements and good clinical staff/student and clinical staff/university staff relationships. The findings indicate teaching methods influence both student retention and students perceptions of support and show that lectures, at least in their current form, appear to be less helpful to student learning while student-to-student methods and learning contracts, such as the SSAMS approach in social work, are highly regarded by students. This is very much supported by other studies including Packham & Miller (2000) who report that peerassisted student support had a positive effect on academic performance with regard to coursework-related activities and Moore et al (2003) who found that retention of physiotherapy students from traditionally under-represented groups was helped by good peer learning relationships while Dix & Hughes (2004) found that use of learning contracts helps nursing students to learn more effectively. These, in addition to peer mentoring, form an integral part of the SSAMS scheme which was highly rated in our study. Our data indicates that feeling respected influences both student retention and student’s perception of being supported. A major part of feeling respected, and therefore feeling supported, lies in the quality of communication. This is reflected in the findings by Trotter & Cove (2005) who concluded that university staff need to be more aware of, and sensitive to, the demands of being a full-time healthcare student with competing commitments of academic work, placements and personal lives. Conclusion In terms of theory development, we seem to be able to make some tentative “generative causal propositions” (Pawson & Tilley 1997, p. 122) from our research into what works for whom and in what circumstances. Non-traditional health and social care students at our University are less likely to leave if there is: Good student – student interaction (e.g., peer assisted learning; peer support) Good student – lecturer relationships (e.g., more appropriate teaching methods; better and more consistent information to students, showing students more respect; more effective and timely assessment feedback) Good student – practitioner/mentor interaction (e.g. robust practice-based mentoring/supervision systems in place; teaching sessions as a part of practice placements) Good communication systems between students, the Faculty and the placement areas It appears that where positive factors are in place, e.g. peer support systems, these exert a positive influence on student retention. Where negative factors exist (e.g. lack of care and respect, poor teaching practices) these exert a negative effect on retention. However, theory building in realistic evaluation (Pawson & Tilley 1997) involves a constant interaction between abstraction and specification (or between theory and data). Such cumulation can only take place over time and with continued evaluation research into what enables/helps non-traditional students to succeed at university. 23 A picture is emerging about the kinds of support that make a difference to retention, and the times during the student life cycle when specific support is required by specific student groups. The projects being undertaken in the second phase of the Supportive Learning Environment Project are addressing many of these issues. 24 References Clarke CL, Gibb C & Ramprogus V (2003) Clinical learning environments: an evaluation of an innovative role to support pre-registration nursing placements. Learning in Health and Social Care, 2, 2, 105-15 Connor, H. et al. (2001) Social Class And Higher Education: Issues Affecting Decisions On Participation By Lower Social Class Groups, DfEE Research Brief 267, Dix G. & Hughes S.J. (2004) Strategies to help students to learn effectively. Nursing Standard, 18, 32, 39-42 Durkin, K & Main, A (2002) Discipline-based study skills support for first-year undergraduate students, Active Learning in Higher Education, 3, 1, 24-39 Entwistle N. (2000) Promoting deep learning through teaching and assessment conceptual frameworks and educational contexts. Paper presented at the TLRP Conference, Leicester, November, 2000 Gidman J. (2001) The role of the personal tutor: a literature review. Nurse Education Today, 21, 359-365 Hall, J., May, S. & Shaw, J. (2001) "Widening participation - what causes students to succeed or fail? "I did all the assignments but I didn't hand them in because they were rubbish"", Educational Developments, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 5-7. Heatley S. (2004) Widening Participation Project: improving the first year experience. (Report submitted to South West London Strategic Health Authority and Kingston University Widening Participation Unit). Kingston University Higher Education Funding Council for England (2001) Strategies for Widening Participation in Higher Education: a guide to good practice. HEFCE, London Laing C. & Robinson A. (2003) The withdrawal of non-traditional students; developing and explanatory model. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 27, 2, 175-185 MacDonald C. & Stratta E. (2001) From access to widening participation: responses to the changing population in Higher Education in the UK. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 25, 2, 249-258 Mackie, S.E. (2001) "Jumping the hurdles - Undergraduate student withdrawal behaviour", Innovations in Education and Training International, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 265-276. May S. & Bousted M. (2004) Investigation of student retention through an analysis of the first-year experience of students at Kingston University. Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 6, 42-48. Moore et al (2003) Comparison of recruitment, selection and retention factors: students from under-represented and predominantly-represented backgrounds seeking careers in physical therapy. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 17, 2, 56-66 25 Packham G. & Miller C. (2000) Peer-assisted student support: a new approach to learning. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 24, 1, 55-65 Parmar D. & Trotter E. (2005) Keeping our students: identifying factors that influence student withdrawal and strategies to enhance the experience and retention of first year students. Learning and Teaching in the Social Sciences, 1, 149-168 Parry G. (2003) A short history of failure. In: Failing Students in Higher Education (eds. M. Peelo & T. Wareham), pp. 15-28. Open University Press/SRHE, Buckingham Pawson R. & Tilley N. (1997) Realistic Evaluation. Sage, London Rhodes C. & Nevill A. (2004) Academic and social integration in higher education: a survey of satisfaction and dissatisfaction within a first-year education studies cohort at a new university. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 28, 2, 179-193 Tinto V. (1987) Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition. University of Chicago Press, Chicago Trotter E. & Cove G. (2005) Student retention: an exploration of the issues prevalent on a healthcare degree programme with mainly mature students. Learning in Health and Social Care, 4, 1, 29-42 Tysome, D (2003) The strongest links – learning skills in higher education, Times Higher Education Supplement, 23rd May 2003. University of Bradford/Action on Access (2002) Achieving Student Success: An Analysis of HEI Widening Participation Strategies and the Proposed Impact on Student Success. University of Bradford Van Rhyn W.J.C. & Gontsana M.R. (2004) Experiences by student nurses during clinical placement in psychiatric units in a hospital. Curationis: South African Journal of Nursing, 27, 4, 18-27 Yorke, M. (2000) "The Quality of the Student Experience: what can institutions learn from data relating to non-completion?", Quality in Higher Education, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 61-76. 26