2009 Assessment Schedule (90657)

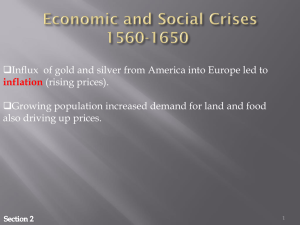

advertisement