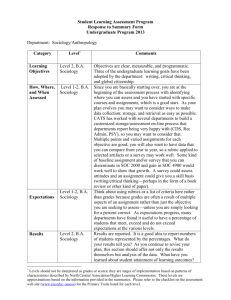

paper - Pedagogic Quality and Inequality in University

advertisement

A Bernsteinian Analysis of Quality and Inequality in Undergraduate Sociology Curricula. Andrea Abbas, Monica McLean and Paul Ashwin Introduction ‘Pedagogic quality and inequality in university first degrees’ is a three-year ESRCfunded study exploring pedagogy and curriculum in undergraduate sociology in four distinctively different universities. It aims to challenge the orthodoxies of league tables by empirically investigating pedagogic complexities and by proposing conceptualisations of pedagogic quality which incorporate a full range of educational goals and which contribute to social inclusion. The project is framed by Basil Bernstein’s work which demonstrates how forms of knowledge and pedagogy express and contribute to distributive injustices in society. League tables purport to measure the quality of degrees. Yet, a pilot study for the current project revealed ‘systematic biases’ (Bernstein, 2000) underpinning judgements about quality (Abbas and McLean, 2007). Curriculum documentation was compared from sociology degrees taught in an elite university near the top of the league tables and in a ‘post-1992’ university near the bottom. While a Bernsteinian analysis showed how boundaries between the sociology teaching at the two universities are drawn and maintained, straightforward judgements about variation in quality was not possible: similar academic materials were present in both degrees and possibly the diversity of pedagogical practices in the less prestigious university is more educationally beneficial than the narrower range in the elite university. We are interested in exploring whether the life advantages of the students in the more prestigious universities are justified by the quality of their knowledge and understanding of what they study. The current project began a few weeks ago and, similarly to the pilot study above, the first task has been to understand differences between the research sites as expressed in publicly available material (websites, handbooks, statistical information)1. Here we report an analysis of three of the research sites in terms of the Bernsteinian concepts of ‘classification’ and ‘frame’. The three universities we deal with here are differently located in published league tables: Kipford is near the top; Endale in the middle; and, Rilgate, the one ‘post -1992’ university, is near the bottom. Theoretical Framework Bernstein has written: ‘How a society selects, classifies, distributes, transmits and evaluates the educational knowledge it considers to be public, reflects both the distribution of power and the principles of social control. From this point of view, differences within and change in the organization, transmission and evaluation of educational knowledge should be a major area of sociological interest.’ (1971, p.47) The focus of such a study should be of ‘three message systems’ (ibid.) through which formal educational knowledge is realised and shapes experience and identity: ‘Curriculum defines what counts as valid knowledge, pedagogy defines 1 Later we will analyse programme documentation which is supplied to us. what counts as valid transmission of knowledge, and evaluation2 defines what counts as valid realization of the knowledge on the part of the taught’ (ibid.) Here we focus mainly on data about curriculum and to a lesser extent about pedagogy and evaluation (which we will be investigating later through other methods including course documentation, interviews, observations, examination of students’ work). Classification is the way boundaries are created and maintained between categories. One major classification that we work with is that made between universities in the UK which is expressed in several different ways -old/new; prepost 1992; elite/local; Russell group and others; research/teaching universitieseach of these binaries is hierarchical, and, by and large, the former of each binary enjoys more wealth and prestige than the latter. The insulation between them is high, though not complete. The second form of classification we consider here is whether the classification of sociology as a curriculum ‘recontextualised’ (Bernstein, 2000, p.56) from the field of research production differs in different universities. Framing, on the other hand, operates to control relations and practices within a category. In terms of curriculum it refers to how it is transmitted. How strong or weak classification and framing is reveals the operations of symbolic social control. Here we use the concepts of classification and frame to analyse public expressions about sociology aimed at potential students and their parents also read by the media, researchers, funding agencies etc.). Material conditions at the three universities Ashworth et al (2004) show how the material wealth of universities is directly related to their position in league tables. In the case of the three universities here, a variety of indicators confirm this. The total income and assets for each university in 2005/6 (HESA) corresponded to each department’s location in the league tables: Kipford the highest-rated sociology department has the largest total income which is approximately 4.8 times greater than Rilgate’s; and, Endale’s income is about 4.5 times greater than Rilgate’s. The expenditure per student varies according to the wealth of institutions and this matches the league table position of the three sociology departments (Guardian, 2008). However, the staff-student ratio does not entirely mirror the hierarchy: although Kipford has a much smaller staff-student ratio (SSR) than the other two universities, Endale has a slightly larger SSR than Rilgate. Similarly the valueadded score which refers to the difference between the A-level qualifications and degree result deviates from the hierarchical order of the sociology departments: Rilgate had a higher score than Endale. Notwithstanding these digressions, wealth indicators are strongly tied to positions in the league tables. The number of students from lower socio-economic classes (SECs) attending a university is likely to indicate its relative wealth. In 2005/6 the percentage of students from SECs 4, 5,6 and 7 attending each of the universities reflects the rating of the sociology departments (HESA, 2005/6). Rilgate had nearly twice as many students from these groups as Endale who had nearly 3% more than Kipford. Entry A-level points indicate the SEC of the students: Endale students arrive with an average of 122 more A-level points than Rilgate students and Kipford students with approximately 40 more points than Endale students (Guardian, 2008). Furthermore, early employment statistics suggest that Endale and Kipford students have approximately 20% more chance of being employed in 2 Usually called ‘assessment’ in the UK university context. the first six months after graduation. So wealthier students, who are more likely to go to Kipford or Endale, arrive there with higher qualifications and more life chances than poorer Rilgate students; they then have more money spent on their education and better life chances when they leave. We want to investigate whether differences in the quality of university education can explain the advantages. Boundary drawing and maintenance: ‘mythologising discourse’? How sociology is classified (what it is, what it does, what it is for) allows us to analyse the extent to which universities’ sociology departments stand in relation to each other. In Bernstein’s terms, when contents are highly insulated (strongly classified or framed) from each other they stand in a ‘closed’ relationship to each other, whereas reduced insulation (more weakly classified and framed) allows an ‘open’ relationship. We found a complex picture: there are both some sharply drawn boundaries between how sociology is depicted in the three universities and some blurring of boundaries. Given competition for research funding and for students, universities have an investment in being distinctive, in insulation from others. This boundary tends to be drawn in two specific ways: by conveying a particular type of sociology and by promising a particular student experience of learning sociology and specific career prospects. What counts as sociology For Bernstein, any discipline is ‘a hierarchical organisation of knowledge [with the] potential for creating new realities.’ (1971, p 57). To enter into the creation of new realities, a student of the discipline must acquire ‘a sense of the “sacred”, the “otherness” of educational knowledge’ (ibid. p.56) as distinct from everyday ‘mundane/profane’ knowledge. To some extent, we see Kipford and Endale making stronger claims than Rilgate about the special, esoteric nature of sociology. Kipford’s website draws attention to the vigour and size of the department. Sociology is positioned as ‘scientific’ and its historical, comparative and theoretical aspects emphasised. It is portrayed as focusing on the forces which shape the relations between social life, people, and institutions. There is passing reference only to the relevance of sociology to ‘present-day societies’. How strongly sociology is classified is to some extent revealed in how the discipline is located in relation to other disciplines. Sociology at Endale is in a School with two other social sciences and the staff group contains anthropologists, so sociology is weakly classified in relation to the other disciplines. But, rather than being a threat to the ‘sacred’ aspects of the discipline’, this is presented as a distinct advantage: the combination enlivens the degree and, the range of research centres and the interdisciplinary nature of much of the research is emphasised. Rilgate’s sociology sits in a School composed of a wide range of cognate disciplines of which social sciences comprise one set. Here, though the claims made are modest and brief: social sciences generally are relevant to contemporary society; the university anticipates and responds to change; and the diversity of the student body is benficial. The emphasis is strongly on teaching which is ‘well-renowned and successful’. We can see here how self-classification, supported by league tables and common perceptions of prestige, reinforces reputations. Endale appeals as a dynamic, forward-looking, modern School which manages a weakly classified sociology; while Kipford more quietly proposes a strongly classified traditional sociology. The place of research is perhaps significant in terms of students’ proximity to the field of production of ‘sacred’ disciplinary knowledge. Kipford and Endale (pre1992) emphasise their ‘excellent’ sociological research and position it as globally significant, making strong claims for prestigious status and international reputations. Rilgate, on the other hand, has a one-sentence claim for ‘strong research [which supports teaching] across all disciplines’ in the School. Kipford and Endale have in common naming the researchers and their specialisms (in Kipford’s student handbook, biographies of academic staff are provided which highlight the institutions in which they were educated and the books they have written). In Rilgate, researchers are invisible. The student experience and prospects The student experience of sociology promised at the three different universities differs. Endale stresses the excitement of courses and the excellence of facilities, simultaneously it claims a 40-year long history of sociology and pictures the department in a Victorian building. It envisages the students and tutors as what might be called (after Lave and Wenger [1991]) an elite community of international sociology scholars. At the same time, it describes itself as being relevant and useful in the local economy and polity. The pictures at the top of the main Endale page change every few seconds and include students in the library, on top of a mountain in an exotic location; there are pictures of landmark buildings in the university’s city and a picture of another international city. This depiction is of students comfortable anywhere, as urbane citizens of the world. Similarly, at Kipford students are encouraged to engage in the development of a community of scholars as researchers as well as learners. Interactions with staff on an informal basis, through social events and an annual study trip are also emphasised. Graduates from the degree are presented as having an in-depth knowledge of human societies, the capacity to analyse arguments and interrogate data, and to evaluate critically central issues affecting society. Career routes highlighted are high status private and public sector jobs and postgraduate study. Rilgate’s sociology website addresses potential students directly in two short sentences, which inform them of how the discipline assists individuals to take an objective view of their own beliefs and assumptions and to understand their own position in society. Here sociology is for personal awareness and, perhaps, transformation. More generally, students are depicted as ‘facing’ financial, domestic and other ‘pressures’. Graduates are presented as knowledgeable about social structures, political processes and human responses. A career page of social science students gives specific examples of suitable jobs for graduates: trainee personal (sic) adviser; events organiser; and training manager. An offer to participate in exchange programmes abroad and the opportunity to students clearn a language or to take business based modules, or engage in research or other work in the community might indicate opportunities to move beyond the local for a small number of students. The websites are acting as ‘boundary maintainers’ (Bernstein, 1971, p.51). While the students at Endale and Kipford are being encouraged to see themselves as academic peers, global citizens and as future leaders in various fields; Rilgate’s students are largely being reassured that they will manage their study and gain useful insights which will help them personally and lead to respectable work. Framing: selection of curriculum content Curriculum is produced by selecting elements of the discipline as it is produced in research which are ‘recontextualised’ as BSc Sociology, expressing what counts as legitimate knowledge in the context of university education. Framing includes selection, organisation, sequence of content; and, pacing, timing, and assessment, as well as student/staff relations. Websites tell us most about the selection and sequencing of content, and less about other elements of framing. What we read does not seem to justify the hierarchical classification and location of Rilgate, Kipford and Endale in the league tables: the selection, organisation and sequencing of content in core modules is remarkably similar. Despite differences in status and in material conditions, knowledge and skills that students are expected to learn put the university departments in an open relationship to each other. In all of the universities the first year provides an introduction to sociological theories and themes; and, the students gain grounding in university-level study skills. In the second year, there are core theory courses, which include earlier structural theories and more contemporary social theory. Research methods are largely taught in year two. In the third year the core is a supervised dissertation. The institutions differ in the way sociology combines (or does not) with other degree programmes and disciplines. For example, Endale specialises in social anthropology which core in the first year and remains an important part of the degree. All the degrees appear to involve students engaging with social science disciplines/issues beyond a tight and narrow (strong) classification of sociology. In pilot research we found that titles of optional modules in one elite and one post-1992 university signalled a strong classification of sociology in the elite which used disciplinary or ‘sacred’ terms (e.g. Marxism, Political Sociology). In contrast, the post-1992 used everyday or ‘profane’ terms (e.g. football, emotions) (Abbas and McLean, 2007). However, this difference does not hold in the current study. All the optional modules across the three institutions use mostly mundane titles (youth, crime, work, body, sexuality, global, identities, crime) and little sacred terminology (social theory, ethnography). Sociological content is indicated by the use of terms which have both sacred and profane connotations (e.g. sexualities, globalisation, masculinities, the state). The options do not indicate a degree hierarchy. Further elements of framing While we have not been able to explore the framing of the degrees in depth through the websites (and some contain more information than others), for now we make a few observations. In our pilot research we identified the framing of one pedagogy as ‘elite’ (highly personalised, traditional and expensive) and another as ‘mass’ (standardised, teaching variety and cheaper) (ibid.). The distinction in the current case is not as straightforward. All three departments use lectures and seminars as the main teaching and learning methods; claim to use IT; and use a mixture of exams and course work for assessment- though Rilgate suggests more variety in the form of presentations, book reviews, portfolios and mini-projects. All indicate that students will be well supported in their studies. There are nuanced differences which might or might not be significant. For example, Rilgate identifies ‘diversity’ and being ‘cosmopolitan’ as pedagogical strengths; Kipford depicts seminar discussions between students and academics as between a community of scholars; and, Endfield points out that the lecture themes will vary depending on who gives it. In this Rilgate appears to offer the very composition of the student group as pedagogically attractive; while the two other universities put the research-active staff in the pedagogical spotlight. From a Bernsteinian perspective, it can be argued that Rilgate’s students are being offered less access to ‘sacred’ knowledge, but we cannot yet draw conclusions about pedagogical quality. Conclusion We are at the beginning of our project and our website analysis is a small start on an empirical investigation of Bernstein’s proposal that ‘the structure of society’s classifications and frames reveals both the distribution of power and the principles of social control,’ (1971, p.48). Our interest lies in unearthing whether or not and how there is unequal distribution in university education of what Bernstein calls ‘pedagogic rights’ : to the means of critical understanding and seeing new possibilities; to be included socially, intellectually, culturally, and personally; and, to participate in the construction, maintenance and transformation of social order. Certainly, we can see different material conditions that affect these rights and boundary maintenance at work in how sociology in different universities is classified and framed in website form. It is by no means clear yet whether boundaries that are drawn have a basis in the quality of what students learn. Abbas, A. & McLean, M. (2007) Qualitative research as a method for making just comparisons of pedagogic quality in higher education: a pilot study, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28, pp. 723. Ashworth, P., Clegg, S. and Nixon, J. (2004) The Redistribution of Excellence: Reclaiming Widening Participation for a Just Society, paper presented at the 12th Improving Student Learning Symposium,Inclusivity and Difference, Birmingham, 6-8 September, 2004. Bernstein, B. (1971), On classification and Framing of Educational Knowledge, in in M.F.D. Young (ed) Knowledge and Control: New directions for the sociology of education: London: Collier-Macmillan Bernstein, B. (2000) Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity, Maryland; Rowan and Littlefield. Lave, J. And Wenger, E. (1991), Situated Learning, legitimate peripheral participation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press