Vomiting and Diarrhea - Guidelines for Emergency Department

advertisement

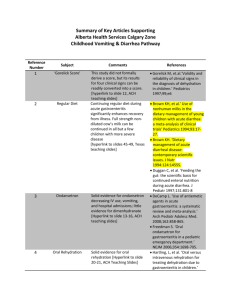

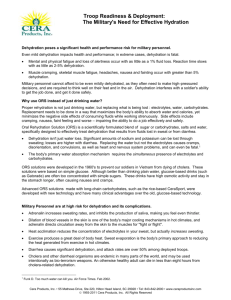

Comprehensive Care Plan Vomiting and Diarrhea in Children: Guidelines for Emergency Department Approach and Management Project Team Itai (Tal) Shavit, MD, Project leader Cheri Nijssen-Jordan, MD, Director, ACH-ED Michelle Ovenden, MD Shannon L Wilson, RN Lori Vollmerhaus, RN Laurie Leckie, RN Irene Milligan, RN Debbie Guyader, RN 2 1. INTRODUCTION 2. EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT TRIAGE OF CHILDREN WITH VOMITING AND DIARRHEA 3. ACUTE GASTROENTERITIS IN CHILDREN A. ASSESSMENT OF DEHYDRATION Risk of dehydration Clinical assessment Laboratory evaluation B. TREATMENT OF THE SEVERELY DEHYDRATED CHILD C. TREATMENT OF MILD TO MODERATE DEHYDRATION D. SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS 4. SELECTED REFERENCES APPENDIX A Intravenous Rehydration Record in Severe Dehydration APPENDIX B Rapid Intravenous Rehydration Record in Children Who Can Not Retain Oral Fluids 3 1. INTRODUCTION Vomiting and Diarrhea represent two of the most common reasons for children to present to emergency departments. Gastroenteritis and associated hypovolemia account for more than 4500 children visits to the Alberta Children’s Hospital Emergency Department, every year. The children arrive in varying states of hydration requiring a multifaceted approach to assessment and treatment. Family members and care providers often arrive with high expectations of advanced treatment (especially intravenous therapy) without that oral rehydration with close follow-up is the best care for the child. Nurses and physicians can have different perspectives on appropriate therapy leading to huge variation in methods of care even within the same emergency team. The following document provides evidence-based recommendations. The guidelines described are based on the most updated studies but intend to provide a general clinical approach only. All medical care personnel should apply medical knowledge and clinical judgment in using these guidelines. The guidelines do not deal with cases in which the history is unreliable (e.g. due to language barrier) or when caregivers are uncooperative. 4 2. EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT TRIAGE OF CHILDREN WITH VOMITING AND DIARRHEA LEVEL I - Resuscitation Conditions that are threats to life (or associated with imminent risk of deterioration) requiring immediate aggressive interventions. Time to physician assessment immediate 1. Cadiopulmonary arrest Patients with cardiac or pulmonary arrest (or imminent arrest) 2. Signs of Shock (at least two) Poor skin perfusion and Tachycardia Altered level of consciousness Vital signs are unobtainable or systolic blood pressure lower that expected for age 3. Unconscious or unresponsive patient 4. Signs of severe dehydration (at least 4 signs) Ill appearance, Dry mucous membrane Sunken fontanelle Sunken eyes Absence of tears Prolonged capillary refill Reduced skin turgor 5. Active seizure 5 LEVEL II - Emergent Emergent, conditions that are potential treat to life, the child requiring rapid medical intervention or delegated acts. Time to physician assessment ≤ 15 minutes 1. Vomiting + Significant Medical history (at least one) Vomiting can be a sign of other problems. These possibilities must be considered: Head injury - These patients may have high-risk mechanism of injury Abdominal injury - These patients may need acute surgical intervention Suspected intoxication History of Diabetes or present complains of polyuria and polydipsia History of gastrointestinal disease History of sickle cell anemia with abdominal pain History of physical abuse History of chronic disease (e.g. Metabolic disease or Immunodeficiency) 2. Risk for acute abdomen (at least one) More than two bile (green) emesis Severe abdominal pain Distended abdomen accompanied by abnormal or reduced bowel sounds Positive peritoneal signs Hematemesis, Bloody diarrhea 3. Risk for Meningitis or sepsis (at least one) Bulging fontanelle Nuchal rigidity Photophobia Purpura or petechiae on skin Hypothermia Age less than 3 month Infants less than 3 months old with a temperature of <36°C or >38°C and a history of abnormal behaviour or abnormal examination are at higher risk of sepsis than older infants. Infants more than 3 months old with fever and a toxic appearance should be rapidly assessed and treatment initiated. 4. Neonates Neonates may present with hyperbilirubinemia, undiagnosed congenital heart abnormalities, bowel obstruction, and sepsis. The signs of serious problems may be very subtle, such as minimal temperature abnormalities, feeding disturbance, or increased lethargy. Parental anxiety is often very high, and these patients should be brought into the ED treatment area and have prompt physician assessment or verbal review. 6 LEVEL III -Urgent Conditions that could potentially progress to a serious problem and requiring emergency intervention. May be associated with significant discomfort or affecting daily function or activities. Time to physician assessment ≤ 30 minutes. 1. 10 or more episodes of vomiting over the last 24 hours 2. Recurrent vomiting over the last 3 days 3. Seizure prior to ED arrival LEVEL IV – Less Urgent Less urgent. Conditions that related to patient age or potential for deterioration or complications would benefit from intervention or reassurance within 1 –2 hours. Time to physician assessment ≤ 60 minutes. 1. Mild or Moderate Dehydration - Risk of dehydration increases when vomiting and diarrhea are both present. Simple viral gastroenteritis does not usually cause serious problems in most children. Signs of dehydration vary by age. Young children may have behaviour or mental status changes that can range from simple fussiness, to being very lethargic or even unconscious. Clues found in vital signs: dry mucous membranes, decreased tears, decreased urine output and skin turgor. Questions should include: how many times the patient has vomited, whether it occurred only when eating or drinking, and time of the last episode (exact times are best). The same is true for diarrhea. If there have been <5 loose bowel movements per day, then dehydration or electrolyte imbalances are unlikely. In children with >10 bms/d (with or without blood) more serious causes should be considered. Patients with 10 or more episodes of vomiting in the previous 24 hours should be upgraded to a level III. 2. Mucousy Diarrhea 3. Diarrhea lasting for more than 5 days 4. 5 or more episodes of vomiting over the last 12 hours 5. Recent close contact with person who had meningitis 7 LEVEL V – Non Urgent Level V conditions may be acute but non-urgent, or may be part of a chronic problem (with or without evidence of deterioration). Investigation or interventions for some of these illnesses or injuries can be delayed or referred to other areas of the hospital or health care system. Level V conditions include the following. Time to physician assessment ≤ 120 minutes. Vomiting alone or diarrhea alone in a child older than 3 months, with no history of high risk, no signs of dehydration, and with normal mental status and vital signs. Always true for Pediatric Triage: If patients look sick they should be triaged as Level I or II 8 3. ACUTE GASTROENTERITIS IN CHILDREN A. ASSESSMENT OF DEHYDRATION Risk of dehydration The evaluation of the child with symptoms of acute gastroenteritis begins with the assessment of dehydration. Risk of dehydration is related to age; young infants are more prone to dehydration. Retrospective case-control studies from developing countries have confirmed that severe symptoms, including frequent vomiting and watery diarrhea, predict an increased risk of dehydration. The severity of dehydration is usefully expressed in terms of weight loss as a percentage of total body weight. If a recent weight record is available (for example, from the parent held medical record) dehydration can be estimated with some accuracy. *Young infants are more prone to dehydration. Try to get recent weight record. Clinical assessment Clinical criteria for the assessment of dehydration were examined in various studies. Signs and symptoms such as ill appearance, dry mucous membranes, sunken fontanelle, sunken eyes, absence of tears, prolonged capillary refill, and reduced skin turgor, can help the clinician to evaluate the degree of dehydration and categorize them into mild, moderate and severe. These conventionally used clinical criteria for evaluating dehydration have been codified by the American Academy of Pediatrics and by the World Health Organization. However, there are major inconsistencies between sources, the criteria have not been validated, and their usefulness have been called into question. One research studied the validity and reliability of various clinical findings and found that the following four findings were independently associated with dehydration: general ill appearance, prolonged capillary refill (>2 sec), dry mucous membranes and reduced tears. The combination of all 4 signs is suggestive for dehydration of 10 percent or more. *In the assessment of dehydration, the clinician must look for combination of signs and symptoms. 9 Laboratory evaluation The sensitivity and specificity of laboratory studies for the detection of dehydration are poor. The majority of children with mild and moderate dehydration do not need laboratory studies. These studies should be used as an adjunctive tool with a comprehensive clinical evaluation in assessing moderate or severe dehydration. It is reasonable to recommend that electrolytes, Urea, creatinine, and glucose be obtained in any child with severe dehydration and in moderately dehydrated children whose history and physical examination are inconsistent with each other or with the presumptive diagnosis of acute gastroenteritis. Clinical reassessment and monitoring of clinical signs during therapy are most important. *In every child with severe dehydration, it is recommended that electrolytes, Urea, creatinine, and glucose be obtained. B. TREATMENT OF THE SEVERELY DEHYDRATED CHILD Initial phase. The initial therapy applies to all forms of dehydration: hyponatremic, hypernatremic or isonatremic. Severe dehydration should be considered as an emergency and has to be treated with a rapid bolus of normal saline or ringer’s lactate. There is no place for colloid infusion, most studies show adequate crystalloid volume expansion to be superior to colloid infusion in severe dehydration. The recommended crystalloid dose is 20 ml per kg of body weight over approximately 15 to 30 minutes or as quickly as possible if there is uncompensated shock. The patient has to be reassessed after each fluid bolus. The bolus may be repeated a second or occasionally a third time until blood pressure is restored, heart rate normalizes and peripheral perfusion improves. If the patient does not respond, the clinician should consider the possibility of an underlying disorder such as septic shock, toxic shock syndrome, or myocarditis. Urine output is the most important indicator of restored intravascular volume and should be monitored using a bag. If patient’s status is not improving and/or signs of shock are present - insertion of Foley catheter is indicated. 10 *The patient has to be reassessed after each fluid bolus. Urine output is the most important indicator of restored intravascular volume. Subsequent Phase. At this time laboratory values are usually available, in particular - serum sodium levels. This phase of treatment is devoted for continued replacement of existing deficit, provision of maintenance fluid and electrolytes and replacement of ongoing losses. Various strategies can be used to calculate these parameters. Hyponatremic/Isonatremic Dehydration: Treatment of hyponatremic dehydration is similar to that for isonatremic dehydration, except that the extra losses of sodium should be taken into account when calculating electrolyte administration. Half of the replacement therapy in addition to maintenance needs to be given over the first 8 hours and the second half over the next 16 hours. Potassium is usually not provided until the patient has voided and demonstrated acceptable renal function. Large amounts of parentally provided potassium can lead to hyperkalemia and cardiotoxicity and should be avoided. The fluids solution recommended after the initial phase is D5¼NS or D5½NS with 20 mEq/L of KCl. Hypernatremic Dehydration: Fluids should be given slowly. Correction of dehydration and hypernatremia may take 48 hours and more. Therapy is adjusted to return the serum sodium levels toward normal by not more than 10 mEq/L/24 hours. If seizures occur, they should be treated with anticonvulsants and intravenous administration of 3-5 ml per kg of a 3% sodium chloride solution. C. TREATMENT OF MILD TO MODERATE DEHYDRATION All children should be treated with Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS). ORS is the preferred treatment of fluid and electrolytes losses caused by diarrhea in children with mild to moderate dehydration. Children who have diarrhea and are not 11 dehydrated should continue to be fed age-appropriate diet. Children who require rehydration should be fed age-appropriate diet as soon as they have been rehydrated. Breast feeding should be continued throughout the rehydration. Which foods are best for re-feeding? Controlled clinical trials showed that certain foods, including complex carbohydrates (rice, potatoes, bread, and cereals), lean meat, yogurt, fruits and vegetables are better tolerated. Fatty foods, or food high in simple sugars should be avoided (including tea, juices, soft drinks). The classic BRAT diet (Bananas, Rice, Applesauce, and Toast) can be tolerated but are low in energy density, protein and fat. *Children who require rehydration should be fed age-appropriate diet as soon as they have been rehydrated. D. SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS Vomiting. Vomiting occurs frequently in the course of acute gastroenteritis and sometimes may be the only manifestation. Vomiting is not a contraindication to attempt oral rehydration therapy. Most of the children who have vomiting can be treated with ORS. Studies have demonstrated that small amounts of ORS can be tolerated by most children. The therapy can be initiated with 5 ml (one teaspoon) given every 1-2 minute. Although this technique is labor intensive, it can be done by a parent and will deliver 150 to 300 ml/hour. Nasogastric continuous infusion of ORS can also be used. Children who can not retain oral rehydration. Some children refuse to drink it because of it’s salty taste, in these cases frozen ice-pops may be a good alternative. There may be several ways to improve palatability; one study showed that small amounts of unsweetened Kool-Aid powder, Jell-O powder, and apple or orange juice can be added to oral rehydration solutions without significantly altering electrolyte composition and osmolality. This study is limited to laboratory data and does not take into account the sucrose and fructose found in fruit juices and Jell-O powder, which could significantly affect intestinal water absorption. 12 The IV route should be to treat any moderately dehydrated child who has persistent vomiting or who does not tolerate oral rehydration. Also, ORS administration requires caregiver’s compliance. If such personnel are not available, IV therapy is indicated. In addition, children with extreme fatigue, illeus or gastrointestinal distention may not be candidates for oral rehydration. Rapid intravenous rehydration in children with mild to moderate dehydration The data in the literature regarding this type of treatment is limited, but this type of treatment seems safe and effective. Isonatremic or hyponatremic patients with mild to moderate dehydration are treated with IV fluids for 2 to 3 hours. Oral rehydration begins immediately after. Few studies have been published on the outcome of children treated with this modality. The investigators used different protocols for IV therapy, and all patients demonstrated clinical improvement. Most of them tolerated oral therapy once the rapid IV rehydration was completed. It seems that rapid IV rehydration may “break” the vomiting cycle more quickly than oral rehydration. Additional studies are needed to validate the safety and effectiveness of this treatment. In any child receiving IV therapy, electrolyte levels should be measured initially and as needed when therapy progresses. Persistent diarrhea (7 days or more of diarrhea). Although persistent lactose intolerance is uncommon, it is suggested that if persisted diarrhea occurred after the reintroduction of milk, stool PH, and stool reducing substances should be measured, and a lactose free formula should be considered if the stool was acid and contained more than 0.5% reducing substances. Microbiological investigation. Microbiological investigation is not necessary in every case, but may be important in patients who require admission to hospital, in those who have bloody or mucoid diarrhea, suggesting colitis, in high-risk patients such as those with an immune deficiency, and in cases where there is diagnostic uncertainty. Antibiotic treatment. Most bacterial gastroenteritis does not require or benefit from antibiotic treatment. Antibiotic treatment should be indicated in the very young 13 infant, in immunocompromised patients, and in those who are severely ill. Antibiotic treatment is also recommended in patients with shigella dysentery infection, in whom the treatment shortens the clinical illness and the duration of pathogen excretion. Although Campilobacter Jejuni gastroenteritis is usually a mild and self limited disease. Treatment is not generally indicated, Antimicrobial treatment (erythromycin) is indicated in invasive cases or to eliminate the carrier state. Antidiarrheal treatment. There is no evidence that these drugs have an effect (Bismuth Subsalicylate may have some effect). There is no role for such drugs in the treatment of gastroenteritis. It is possible that their use may have adverse consequences. 14 4. SELECTED REFERENCES 1. Warren D, Jarvis A, Leblanc L, and the National Triage Task Force members. Canadian Paediatric Triage and Acuity Scale: implementation guidelines for emergency departments. CJEM 2001;3(4 Suppl):S1-27. 2. Murphy MS. Guidelines for managing acute gastroenteritis based on a systematic review of published research. Arch Dis Child 1998;79:279284. 3. Liebelt EL. Clinical and laboratory evaluation and management of children with vomiting, diarrhea and dehydration. Curr op Ped. 1988;10:461-469. 4. American Academy of Pediatrics. Practice parameter: the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. Pediatrics 1996;97:424-435. 5. American Academy of Family Physicians. Burkhart DM. Management of acute gastroenteritis in children. Am Fam Physician 1999;60:25551566. 6. Goepp JG, Hirschhorn B. Fluid therapy of diarrhoea. Industrialized countries. In: Walker WA, Durie PR, Hamilton JR, Walker-Smith JA, Watkins JB, eds. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. Philadelphia: Decker BC, 1991:1567-1576. 7. Lulseged S. Predictors of moderate to severe dehydration in acute diarrhoeal disease: a case control study. Ethiopian Medical Journal 1992;30:69-78. 8. Bhattacharya SK, Bhattacharya MK, Manna B, et al. Risk factors for development of diarrhoea in young children: a case control study. Acta Paediatrica 1995;84:160-164. 9. World Health Organization. The Treatment of Diarrhea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1995. WHO/CDD/SER/80.2 Rev. 3. 10. Mackenzie A, Barnes G, Shann F Clinical signs of dehydration in children Lancet. 1989; ii:1529-1530. 11. Gorelick MH, Shaw KN, Baker MD. Performance of clinical signs in the diagnosis of dehydration in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1994;148:73. Abstract. 12. Nijssen-Jordan C. Can oral rehydration solution be safely flavored at home? Pediatr Emerg Care 1997;13(6):374-5 13. Gorelick MH, Shaw KN, Murphy KO. Validity and reliability of clinical signs in the diagnosis of degydration in children. Pediatrics. 1997;99:5,E6 14. Teach SJ, Yates EW, Feld LG. Laboratory predictors of fluid deficit in acutely dehydrated children. Clin Pediatr 1997;36:395-400. 15. Show KN. Dehydration. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig LS. Textbook of Pediatric emergency Medicine, 4th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA: A Walter Kluer Co;2000:197-201. 16. Adelman RD, Solhaug MJ. Pathophysiology of body fluids and fluid therapy. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, 16th eds. Nelson 15 Textbook of Pediatrics. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co;2000:215216. 17. Mahalanabis D, Snyder JD. Fluid and dietary therapy of diarrhoea. In: Walker WA, Durie PR, Hamilton JR, Walker-Smith JA, Watkins JB, eds. Pediatric gastrointestinal disease; pathophysiology, diagnosis, management. Philadelphia: Decker BC, 1996:1843-1850. 18. Meyer A. Fluid and electrolyte therapy for children. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 1994;6:303-309. 19. Duggan C, Santosham M, Glass RI. The management of acute diarrhea in children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy. MMWR. 1992:41(RR-16):1-20. 20. Moineau G, Newman J. Rapid intravenous rehydration in the pediatric emergency department. Ped Emerg Care 1990;6;186-188. 21. Rahman O, Bennish ML, Alam, AN, et al. Rapid intravenous rehydration by a means of a single polyelectrolyte solution with or without dextrose. J Pediatr 1988;113:654-660. 22. Reid SR, Bonado WA. Outpatient rapid intravenous rehydration to correct dehydration and resolve vomiting in children with acute gastroenteritis. Ann Emerg Med 1996;28;318-323. 23. Scott DA, Edelman R. Treatment of gastrointestinal infections. Ballieres Clinical Gastroenterology 1993;7;477-499. 24. Portnoy BL, DuPont HL, Pruitt D, Abdo JA, Rodriguez JT. Antidiarrhoeal agents in the treatment of acute diarrhoea in children. JAMA 1976;236:844-846. Intravenous Rehydration Record in Severe Dehydration (Acute Gastroenteritis*) ED Pre-treatment assessment Weight Pulse Capillary Refill Blood pressure **Bag urine ≥2sec, < 2sec kg mmHg Y/N ED Treatment, phase I Time Ordered by Time ended Pulse Capillary Refill BP (mmHg) ≥2sec, < 2sec ≥2sec, < 2sec ≥2sec, < 2sec IV 0.9NS 20cc per kg in 20 min IV 0.9NS 20cc per kg in 20 min IV 0.9NS 20cc per kg in 20 min Bag urine Y/N Y/N Y/N ED Treatment, phase II Sodium mEq/L Potassium mEq/L Glucose mmol/L Urea mmol/L Creatinine mcmol/L Maintenance treatment for Isonatremic or Hyponatremic Dehydration (D5W.45NS cc/h): First 10kg - 4cc per kg, Second 10kg – 2cc per kg, Each additional kg – 1cc per kg (Example: 8 year old, weighing 25 kg. For first 10kg – 4x10=40, for second 10kg – 2x10=20, for 5kg – 1x5=5. Total fluids to give: 65cc/h) Time Ordered by Time ended IV D5W.45NS Pulse Capillary Refill BP (mmHg) ≥2sec, < 2sec cc/h Y/N ED Post-treatment assessment Weight Pulse kg Capillary Refill Blood pressure ≥2sec, < 2sec mmHg *This document is inappropriate for children with chronic diseases such as those with congenital heart disease or IDDM, or when diagnosis is uncertain ** Consider Foley Catheter if patient is not improving or signs of shock are present Bag urine 17 Rapid Intravenous Rehydration Record in Children Who Can Not Retain Oral Fluids (Acute Gastroenteritis*) ED Pre-treatment assessment Weight Pulse Capillary Refill Blood pressure Bag urine ≥2sec, < 2sec kg mmHg Y/N ED IV Treatment Time Ordered by Pulse mEq/L Potassium mEq/L BP (mmHg) Bag urine ≥2sec, < 2sec IV 0.9NS 20cc per kg in 2-3 hours Sodium Capillary Refill Glucose mmol/L Urea Y/N mmol/L Creatinine mcmol/L ED Post- IV treatment assessment Weight Pulse kg Capillary Refill Blood pressure ≥2sec, < 2sec Bag urine mmHg ED Oral Rehydration Therapy Oral Rehydration Solution (e.g. Pedyalite) given by parents (~100 to150cc an hour) 1. 10 minutes - 5cc (1 teaspoon) every 1-2 minutes 2. 20 minutes - 10cc every 5 minutes 3. 30 minutes - 20 cc every 10-15 minutes *This document is inappropriate for children with chronic diseases such as those with congenital heart disease or IDDM, or when diagnosis is uncertain Y/N