What is language - The Richmond Philosophy Pages

advertisement

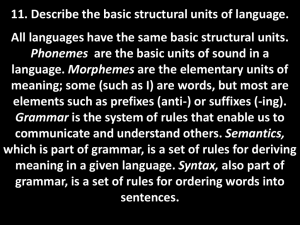

Knowledge and Language One of the ways in which we come to possess knowledge is through our possession and use of language. This raises the issues of why language is so central to our capacity to know and of what limits or constraints language places upon our knowledge. Is our knowledge exhausted by what can be said or can something be known in a non-linguistic form? What is language? Communication Syntax – rules of grammar Semantics – rules of meaning Natural Language - Any language actually spoken, as opposed to artificial languages, whose syntax and rules are laid down for theoretical purposes. Knowledge What is the knowledge? relationship between language How does language influence what we can know? Attitudes Values Practices The challenge and possibility of translation and The Sapir–Whorf hypothesis Does language shape the world? Here is a view that is probably quite widespread in some parts of social science and language and literature departments. We’ll call this the strong relativity thesis (SR). SR The nature of the world depends on the concepts and language I possess (as a member of a particular linguistic and cultural community). This is a strong thesis because it claims that the (real) nature of the world is determined by my concepts. This seems to invert the relationship between world and mind. My claims to knowledge might be circumscribed in many ways and I may regard truth as a feature of how we talk about the world rather than as determined by the world. However, such considerations do not undermine the idea that the existence and nature of the things in the world are independent of what I think of them. This thesis of independence is a central feature of realism. SR, though, is probably held because a more plausible thesis is sometimes given too strong an interpretation. This thesis is the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (SW), a widely used label for the linguistic relativity hypothesis. SW The particular language we speak shapes the way we think about the world. Our language shapes the way we conceive of the world. It does not change in any literal way the shape of that world. Categories or concepts that may be very different between languages include those of time, causation, and the self. Note that some superficial examples of diversity that are frequently cited are in fact spurious. It is not true, for example, that the Indo-Aleut languages have a vast number of words for different varieties of snow. Does thinking about the world in different ways mean that different linguistic/ conceptual communities possess distinct kinds of knowledge? Does it mean that there are some things which are unknowable for those who do not share the language? What is the relationship between language and culture? How is language possible? What must we know to be language users? When you were born you were remarkably poor in your use of English or any other language. Along with every other (non-impaired or isolated) human infant you became a proficient user of a language(s) in a relatively short time. By the age of about three you – all of us – display linguistic understanding and the ability to produce a wide range of grammatical sentences. How can we be language users? What is it that we know? One influential and widely accepted answer in the first half of the twentieth century is essentially an empiricist claim. Developed by behaviourists like the psychologist B. F. Skinner the claim was that we acquire language through a process of stimulus response. That is, we come to be language users through the experience of being immersed in a world of language users. A child learns through imitation and repetition? A word through repetition becomes associated with a particular stimulus – a particular sensory experience. Cake The key to explaining our acquisition of language is the presentation of appropriate sensory experiences at appropriate times and in appropriate combinations. Knowledge of language is built up through our experience (via the senses) of the world. We can agree that experience is necessary for the development of our knowledge of language. However, there are big problems with the view that language is somehow just acquired by having the right kind of experiences in the right kind of environment. Noam Chomsky Chomsky: the central figure in a major change in the study of linguistics from the late 1950’s. Big problems with the behaviourist view The competence of an adult, or even a young child, is such that we must attribute to him a knowledge of language that extends far beyond anything that he has learned. Compared with the number of sentences that a child can produce or interpret with ease, the number of seconds in a life is ridiculously small. Hence the data available as input is only a minute sample of the linguistic material that has been thoroughly mastered, as indicated by actual performance. We should be struck by the meagreness of the available data or experience in relation to the extent of rapidly acquired linguistic competence. We’re not going to get from our experience of associating words with features of the world and practices to the kind of linguistic competence we actually have. Moreover, we should note the creativity and compositionality of language. There seems no obvious limit on what we could say. From a finite number of words and rules we can compose entirely new sentences. Once we have even a modest competence in a language we can produce and interpret (i.e. understand others) sentences we have never heard before. Badgers might howl when there is a danger in the environment or gibbons gibber, and in this sense communicate something about the world to their fellow beasts. Chomsky notes that full-blown language is not stimulus dependent in this way. Human language can be produced independently of environmental stimuli or the occurrence of certain internal states. How to explain these facts about human language? Commonality of basic grammatical structures. Universal grammar Innate – hard-wired – knowledge or capacity to develop linguistic competence in general (i.e. in any language). Languages share a common ‘deep structure’. The particular form of an individual language presents the infant with a particular set of data. The innate capacity enables the child to map the surface features of English, Japanese or whatever onto the deep grammar. A child can thus manage to construct a grammatical model which enables her to interpret and produce sentences in the language.