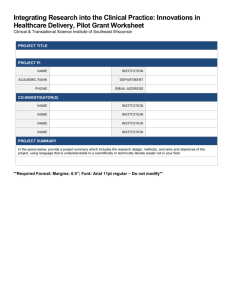

Business Case and Intervention Summary

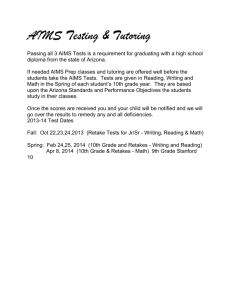

advertisement