Independent Living Policy development paper

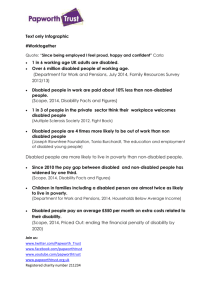

advertisement

Independent Living A policy development paper on disability Danny Alexander MP 2 Foreword The purpose of this paper is to develop a long-term framework for Liberal Democrat policy on disability. It represents our long-term ambition to significantly improve the position of disabled people in society. This papers contains policy proposals to deliver this aspiration – much like the Prime Minister’s strategy unit report, Improving the Life Chances of Disabled People, it should not be seen as a list of shortterm spending commitments. These will be spelled out in our manifesto at the time of the next general election. Specific proposals for reform of the benefits system will be brought forward through the Poverty and Inequality working group that has recently been established. Nor is this paper intended to be over-prescriptive. In many of the policy areas discussed, there will be changes over time that will mean it would be inappropriate to lay down detailed policies now. Rather, the general approach of this paper is to ensure that future decisions are taken within the overall policy framework of Independent Living. In a fair society being disabled should not mean a person is more likely to be in poverty than a non-disabled people. However, 29% of households with a disabled adult are in poverty compared to 17% of households without a disabled adult. It is therefore not surprising that research by the Department for Work and Pensions has found that the extra costs to disabled people are not currently met by the support they receive through benefits and services. With an ageing population, the number of disabled people should be expected to increase. The Disability Rights Commission estimate that within 35 to 40 years there could be nearly a 60% increase in demand for support from carers. Addressing some forms of inequality, such as the age discrimination that exists in regard to some disability benefits, would call for significant extra resources. 3 So to make independent living a reality for disabled people, when decisions are made on the reallocation of resources resulting from greater economic activity of disabled people, closing the gap between extra support provided to disabled people and the extra costs faced by disabled people should be a priority. Greater independent living is not only beneficial for disabled people, but also for society as a whole. Helping those of working age to find employment delivers additional economic growth tax revenue, and lower benefit expenditure. For older people independent living also delivers substantial wider benefits and savings. Danny Alexander August 2006 4 Summary and Recommendations This paper sets the overall direction for the future development of our policies for disabled people. It sets out proposals that will enable disabled people to enjoy the same rights that other citizens expect. The main proposals to meet these aims that are discussed in this paper are: Rights to Independent Living Consultation on updating of existing legal definitions of disability and replacement of ‘duty of care’ with ‘duty of equality’ Monitoring and enforcement of equality legislation Public awareness initiatives, particularly to promote equality of disabled people Services for independent living Establishment of network of Centres of Independent Living (CILs) Central government to undertake a financial impact assessment of the commitment to CILs network Central government to work with regional government offices and local authorities to assess the existing and potential capacity of Direct Payment Support Services (DPSS) Consultation with public private and voluntary sector service providers on changes that may be necessary to: o Promote the growth and regional coverage of a strong DPSS sector o Provide a robust regulatory regime to ensure a level playing field for the public, private and voluntary sectors and ensure high standards of service and protection of disabled people from abuse and substandard DPSS providers. Roles of CILs An ethos and a democratic structure allowing all users an opportunity to participate in decisions on how the CIL is managed and the services it provides Provide brokerage services for use of individual budgets A one-stop point for information and advice Serve all disabled people, including older people and parents of disabled children 5 Requirements for direct payments and individual budgets Inclusion of as many funding streams as possible Advocacy services to support budget holders Genuine choice of services Choice for budget holders in level of responsibility exercised Protection of budget holders through regulation of services Available to parents and guardians of disabled children Health and Care services Greater co-ordination between health services and social services Improved prevention and early intervention Consultation on the merits and the impact of a right to request not to live in residential care A sufficient, better trained, social care workforce Roaming packages to ensure entitlements are valid from one area to another Funding for hospice care for terminally ill children Disability equality training for all health and social care staff Education and transition to adult life A stronger duty on LEAs to provide places in a mainstream school or access to special schooling A stronger duty on Trust Schools to accept disabled children A right to advocacy to help parents and their children make decisions on the best provision in their individual case Disability equality to be part of the citizenship curriculum Disability equality in teacher training programmes Radically overhaul the SEN system to one in which the every child has an assessment of their individual learning needs, with clear best practice guidance Link funding to assessments of learning needs, rather than funding schools on simple headcount that assumes the cost of education every child is identical, regardless of whether they are disabled or have SEN Ensure there are sufficient statutory requirements on Academies and Trust Schools to take disabled and SEN pupils and to work in cooperation with other schools to meet the needs of such pupils. A national strategy to provide an equitable and easily understood system for planning, funding and placement of disabled and SEN learners in further and higher education Centres for Independent Living having a role assisting learners in their transition and brokering provision of further and higher education within the locality or region 6 Employment and Welfare Extra support benefits Include a new category of communication needs in Disability Living Allowance Extend entitlement to the higher rate of the DLA mobility component to people who are registered blind. Address age discrimination in the benefit system Job retention A formalised entitlement to rehabilitation leave Extend Access to the Condition Management Programme (CMP) to those on sick pay or rehabilitation leave Consultation on inclusion of mental health conditions in employer liability Separation of benefit processing from employment support Job Centre Plus to be reformed as a purchasing and regulating body with regional and local presence and a gateway to income replacement benefits and employment services Employment and job search support to be procured from a range of public, voluntary and private providers and partnerships based on clear objectives with stable contracts and funding Support programmes to meet all needs Reform of the Personal Capacity Assessment (PCA) focussed on providing individual action plans and improved understanding of disability, and in particular mental health problems Investment to ensure access to health management, work experience, training and employability programmes Reform of Access to Work so that decisions are made for individuals when seeking work, rather than for a specific job once it has been offered Support for employers Promote use of Access to Work with employers Partnership with employment support providers Promote disability confident businesses Government to lead by example in employing disabled people 7 Home and family life Housing Incorporation of the Lifetime Homes Standard (LHS) into building regulations A requirement for local authorities to maintain an accessible housing register An enhanced duty on local authorities to ensure sufficient provision of accessible housing their area New powers to ensure disabled people can be housed in localities with best access to transport and services for disabled people Transport Extending DDA duties to cover scooters on trains Disability equality training for rail network station staff Addressing the abuse of disabled parking facilities Protect disabled drivers from the impact of congestion charges and roaduser charges Extend parking fines to drivers who block accessible features of the built environment. Enforce DDA requirements for buses and provision of accessible buses on designated accessible routes Prevent non-disabled people blocking access to designated seating for disabled people Support new European laws on air travel for disabled people Extend Disability Discrimination Act requirements to passenger sea craft Carers A right to access employment support programmes Ending the 21 hour study rule on carers Carers to be entitled to working tax credit if employed for more than 16 hours per week A right to respite breaks Relationships Disability equality training for family planning professionals Leisure and social lives Disability equality training for customer facing staff in the leisure sector Increase in the amount of audio description television programmes 8 Introduction Liberal Democrats believe in a society which is fair and in which no-one is enslaved by poverty, ignorance or conformity. Disabled people experience greater poverty, have lower educational attainment and are often left to depend on uniform services that limit their life chances. Since the last Liberal Democrat paper on disability, 1999’s Breaking Down Barriers, there has been considerable legislative change, particularly with the extension of the Disability Discrimination Act. Ideas are changing too. Liberal Democrats must respond to disabled people’s wish to take responsibility for their own lives through independent living; and we must test our policies against the social model of disability. Understanding Disability Disability is not simply about medical diagnosis or health condition. Disabled people may have particular medical needs, but disabled individuals should not have their personal identity medicalised any more than non-disabled people. A social model of disability provides a valuable understanding from which to approach policy making for disabled people. A social model focuses attention on the barriers that policies must address so that more disabled people experience the same life chances as non-disabled people. However, definitions are necessary to allow objective decision-making and more work is needed to frame a definition of disability under a social model which also allows clear decision-making. Failure to understand disability leads to prejudice against disabled people. This prejudice is perhaps the greatest barrier preventing disabled people from having the same life chances as non-disabled people. By addressing society’s negative assumptions about disabled people we can help to overcome their exclusion. For Liberal Democrats this exclusion is unacceptable. The cost of disability discrimination extends beyond disabled people themselves. A million disabled people who are not in employment say they would like to work. Their exclusion from work is a loss to the economy and a cost to the tax payer. There is also a social cost to the whole of society in keeping our diversity hidden and excluded. Independent Living Liberal Democrats believe in upholding human rights, yet disabled people frequently face infringement of both their human and civil rights. 9 Disabled people have responded by demanding rights to independent living. This does not mean unassisted living, but it means having the same choices and freedoms as non-disabled people. The purpose of independent living is to enable disabled people to play their part in society as full and equal citizens, with the rights and responsibilities that entails. This includes a right to the same choices and controls as non-disabled people in areas such as education, work, care and leisure. Choices must be made at the individual level, with high quality independent advocates provided if necessary. We recognise that many of the barriers to independent living result from lack of resources. It is unrealistic to expect unlimited resources. However, we believe that change is necessary. As disabled people make a greater contribution to the economy, and as the economy grows, there is a strong argument for making it a priority to close the gap between the level of support currently provided to disabled people and the extra costs they face. Scope of the paper As in our last paper giving policies for disabled people, we have avoided the temptation to discuss different types of impairments. For independent living to be achieved, disabled people must be treated as individuals. Some may have similar impairments, but different individual aspirations. We need a policy framework the effectiveness of which does not depend on a disabled person’s particular impairment. Legal definitions of disability are less important than the provision of universal legal rights that disabled people can have recourse to when necessary. A rights based approach can also more effectively address the simultaneous discrimination which can affect disabled people who experience other forms of discrimination – for example on the basis of age, gender, sexual orientation, or race. As a policy development paper, this paper seeks to build upon, rather than replace, the Party’s 1999 Policy Paper ‘Breaking Down Barriers’. While some of the proposals in the 1999 paper have been overtaken by subsequent legislation, other proposals remain party policy. This policy development paper was commissioned by the Federal Policy Committee. While the paper is principally intended to aid development of Federal Party policy, it is recognised that parts of the paper cover areas for which the Party in England, the Scottish Liberal Democrats, the Welsh Liberal 10 Democrats and the Northern Ireland Local Party determine policy. In particular, it is recognised that in areas of policy which are the responsibility of the Scottish Liberal Democrats, some of the proposals in this paper are not directly applicable due to changes which have already been driven forward by the party in government in Scotland. Any formal adoption of specific proposals contained in the paper must take place in accordance with the constitutional requirements of the Federal Party and its constituent bodies. 11 The Right to Independent Living Independent living is a fundamental right. Whilst rights should be enshrined in statute, they must not only exist on paper, but throughout society and the attitudes of both its disabled and non-disabled members. Equality Legislation We need to move towards a rights based approach to protection of disabled people, with equality at its heart. For disabled people to progress in society, and attain greater independence and equality with non disabled people, we need to move away from legal definitions that categorise disabled people and enshrine the duty of the state towards them in a paternalistic role. Update existing legal definitions of disability and replace a ‘duty of care’ with ‘duty of equality’ Some of the legal definitions of disability that are still in use are in legislation that was drafted more than 50 years ago. The statutory ‘duty of care’ for local authorities is also coming under increasing criticism for being outdated and resulting in practices that increase dependency. Consultation is required on how a combination of a rights-based framework and legal definitions of disability rooted in a social model can more effectively meet the needs of disabled people. Monitoring and enforcement of equality legislation For equality legislation to work effectively for disabled people, it needs to be properly monitored and enforced. The new Commission for Equality and Human Rights must be sufficiently resourced to do this job. Consideration should be given to the extent to which it should have an inspectorate role for public bodies. It could work in similar way to the Benefit Fraud Inspectorate in providing reports to identify areas for improvement, rather than simply lambasting failure. Discrimination and abuse In a survey conducted by Scope, 22% of disabled respondents reported having experienced harassment in public in relation to their impairment. Abuse of disabled people in residential care continues to be a serious problem. Public awareness initiatives Throughout this paper, areas are identified where a greater understanding of disability equality is needed. These will help improve public attitudes towards disabled people, but to assist disabled people in become more active and visible in our society a more general approach to addressing public attitudes is likely to be necessary. The government should not necessarily take a lead role on this, but should support it as far as possible. The New Office for Disability Issues is probably best situated to take a lead. 12 Portrayal of disabled people The under representation of disabled people and negative portrayal of disabled people in the media is still a frequent occurrence. There is a role for the Office of Disability Issues in encouraging a more balanced and fair portrayal of disabled people, working with the Press Complaints Commission. Democratic participation There are still many barriers to disabled people participating as equal democratic citizens in the running of their country. The most basic right, the right to vote, can even be difficult for many disabled people. Much more proactive use needs to be made of the Disability Discrimination Act to enforce the democratic rights of disabled people, including making polling stations more accessible, and disability equality training for returning officers. 13 Services for independent living The great challenge for a policy based on delivering independent living is to meet the vast diversity that exists amongst the disabled population. The type of impairment a disabled person has and the age at which they became disabled, as well as their individual abilities and wishes, calls for a framework that allows for diversity in the extent to which independence is exercised in accessing services. For example an elderly person whose vision has recently become seriously impaired may prefer a standard package of support rather than take on the complicated personal management of their entire care package. However, a person with a long experience of living with a physical impairment may have very clear ideas about the kind of support that will best meet their personal aspirations and would wish to exercise control over the spending of as many pooled support budgets as possible to meet those aspirations as effectively as possible. The move away from paternalistic provision towards achieving independent living does not mean unassisted living. It is important that the structure that emerges meets the needs and choices of all disabled people, not just the most articulate and outspoken advocates of their right to independent living. Individual budgets and Centres for Independent Living The move to user-led organisations and individual budgets will provide the opportunity for many disabled people to procure services that reflect their individual needs and aspirations. However, those disabled people should not be overlooked who do not wish to exercise this extent of control and whose greatest need is to know that there is quick provision of the support they need based on expertise that they do not possess themselves about their impairment and likely needs. Centres for Independent Living (CILs) The Government accepted the recommendation of the Strategy Unit report, Improving the Life Chances of Disabled People (2005) that each local authority area should have a user-led Centre for Independent Living (CIL) by 2010. This is an important commitment and will not succeed if local authorities do not receive support from central government. 14 As a priority, we need: Central government to undertake a financial impact assessment of the commitment The commitment will doubtless have cost implications. Despite adopting the commitment, the government has so far had nothing to say on possible need for central funding. The Strategy Unit called for consideration to be given to funding implications in the next spending review, but without an assessment of the resources required to ensure an effective network of CILs, the is little chance that there will be a decent outcome for CILs in the spending review. Central government to work with regional government offices and local authorities to assess the existing and potential capacity of Direct Payment Support Services (DPSS) Consultation with public private and voluntary sector service providers on changes that may be necessary to: o Promote the growth and regional coverage of a strong DPSS sector o Provide a robust regulatory regime to ensure a level playing field for the public, private and voluntary sectors and ensure high standards of service and protection of disabled people from abuse and sub-standard DPSS providers. CILs are not generally service providers and a network of CILs is not envisaged as a network to deliver services. One of their main roles will be to provide advice, advocacy and brokerage for disabled people using individual budgets to procure services from providers, so the growth of the DPSS sector is as essential a part of the move towards independent living as a national network of CILs. The proposal in the Strategy Unit report called for each Centre for Independent Living to be modelled on existing user-led CILs. However, there is great variation in services that existing CILs provide. This is due to factors such as differences in ethos, demand and resources. Each CIL does not have to have the same structure of ownership and management; being user-led does not preclude CILs having public, voluntary sector, mutual or private ownership and management structures. But a clearer idea is needed of the kind of services and support that CILs should provide than is given in the suggestion that they should be modelled on existing centres. Each CIL should as a minimum: Have an ethos and a democratic structure allowing all users an opportunity to participate in decisions on how the CIL is managed and the services it provides Whatever ownership and management models each CIL uses, their governance should allow full participation and involvement of users. This may for example, be in the form of a board of governors democratically elected by the CIL’s users. Beyond the democratic involvement of users, 15 each CIL needs a user-led ethos for provision of its services that is understood by all staff. Provide brokerage services for use of individual budgets Disabled people will need advice and support in using individual budgets. Brokerage services should not only provide this, but should protect disabled people from the bureaucracy that may arise in the management of individual budgets and procurement of services. Be a one-stop point for information and advice Disabled people need specialist advice on many areas of their life, e.g. benefits entitlement, education and training opportunities, legal entitlements in a range of situations, accessible goods and services. Provide independent advocacy services For some CIL users, provision of information on their rights, entitlements and choices in different situations will be enough. But not everyone is able to self-advocate. Some may lack the knowledge, expertise or confidence, while others may not be able to because of the nature of their impairment or condition. Serve all disabled people, including older people and parents of disabled children CILs must be able to respond to the needs of all disabled people, whatever their age. Being user led carries an inherent danger that the most articulate or larger groups of disabled people who are subject to the same type of disabling barriers dominate the organisations at the expense of the interests of the less articulate and those with the least common requirements. CILs should be inclusive organisations for all disabled people. Direct payments and individual budgets Piloting of individual budgets is underway that will provide an evidence base. It is too early to be prescriptive about how individual budgets should work in practice and flexibility is likely to be needed; but the following features should be present: Inclusion of as many funding streams as possible The pilots should allow for as many services and funding streams from all relevant government departments and agencies to be offered as part of an individual budget instead as are necessary to deliver independent living opportunities. Independent Advocacy As discussed above, not all disabled people are able to self-advocate. However, they can still achieve greater independence and selfdetermination through the use of individual budgets with the support of an advocate than they can do through the provision of uniform services. 16 Genuine choice for services As mentioned above, those taking advantage of individual budgets will face a barrier to independence and equality if a range of equality service provision is not available for them to procure. Because of the dominance of the public sector in providing services, the relationship between the provider and the disabled person is likely to change before there are genuine alternatives available. But the growth in alternatives is vital to enabling disabled people to achieve independent living. Choice in level of responsibility exercised Not everybody wants to take full responsibility for every aspect of their own support requirements. Disabled people would find themselves subject to a new form of discrimination if they were forced to take responsibility to an extent that non-disabled people do not have to. Protection / regulation People sometimes make poor decisions for which they are responsible. But people can also be taken in by rogue service providers or suffer from poor quality service. There will therefore need to be a robust system of regulation of Direct Payment Support Services across the public, voluntary and private sectors to protect disabled people from rogue providers and poor quality services. A harder decision needs to be made on where to draw the line in protecting people from the problems that could result from bad decisions made on the use of their budgets. Available to parents and guardians of disabled children So far piloting of individual budgets has been mostly focussed on disabled adults, but disabled children should also be able to access individual budgets. Their parents or guardians would generally need to have an advocacy role, but as far as possible disabled children should be encouraged to speak for themselves. Health and Care services Individual budgets will change the relationship that disabled people have with provision of health and care services. But the NHS and local authorities will still continue to have major roles and need to take a more co-ordinated approach. The level of support that some disabled people either need or have provided to them has left many institutionalised. There is evidence that the dependency that results from institutional care is not only a barrier to developing independence, but can adversely affect health. There are also ways in which health services for disabled people can be improved. The main areas of health and social care that should be addressed are: Greater co-ordination between health services and social services The distinction between health and social care is often unclear, but there are artificial divides between health services and social care services. The most effective model for health care is a social model that treats not just 17 the condition or impairment, but takes a more holistic approach to the individual and their environment. To avoid problems of duplicated provision, gaps in provision, delays in provision and confusion over who is responsible, health and social care services need to work much more closely. This is already the case in some areas, where local authorities and hospital trusts and PCTs have found their own ways of working together more closely. Central government must help spread best practice and look at areas where changes to legislation and funding structures could ensure a more streamlined approach. Improved prevention and early intervention One area where health and social services will continue to have a vitally important role - that CILs and individual budgets are unlikely to change is with newly disabled people. Identifying an emerging impairment or health condition and acting early can prevent deterioration of health and loss of independence, which benefits not just the individual but brings valuable efficiency savings. Newly disabled people will not be in contact with CILs and may even be hostile to the idea that they are disabled. Clear lines of responsibility and a more proactive approach are needed by health and social services to ensure that early intervention with the most effective support for maintaining health and independence is provided. Consultation on the merits and impact of a right to request not to live in residential care The question of whether there should be a right to request not to live in residential care was raised in the 2005 green paper on social care, Independence, well-being and choice. However, the government has since avoided pursuing the idea. There are clearly practical and cost implications that may not be possible to overcome in every case, but this could be taken into account. It would prevent residential care decisions being taken for reasons that suit local authorities’ social services departments, rather than the individuals concerned. A sufficient, better trained, social care workforce The government estimates that there is a shortage of 110,000 care workers (11% of the necessary workforce) and that only 25% of the workforce has a relevant qualification. The regional picture in many areas is worse, with rural areas often the worst affected. The main impact of this situation is a lower quality of care provided to disabled people. Roaming packages to ensure entitlements are valid from one area to another When disabled people move to another area, they face the prospect of being re-assessed for their social care needs. While a new location, new home or other life changes may require changes to the services received, many needs stay the same and should not need to be reassessed, which not only costs the local authority but can be stressful for the person affected. Roaming assessment packages could simplify the process and 18 help lead to a more consistent level of service provision across local authorities. Funding for hospice care for terminally ill children The way in which Primary Care Trust spending operates has meant that while adult hospices usually receive some PCT funding, children’s hospices are receiving none and are entirely dependent on charitable sources. Disability equality training for health and social care staff For some disabled people, an impairment or health condition will mean more contact with health services than many non-disabled people. All NHS staff need a level of core skills in disability equality, not just those who most regularly provide treatment and support to disabled people. CILS to advise on Community Equipment Services Lack of funding within the NHS means that currently many disabled people have to self fund or approach charities to get their equipment needs met. This results in many disabled people having inadequate or inappropriate equipment. In particular there are shortfalls in the provision of appropriate wheelchairs, augmentative and alternative communication equipment and other assistive technology which is vital to enable disabled people to live independent lives. Education and transition to adult life Disabled children are not lacking in aspiration; but there remain barriers to them reaching their full potential. This can prevent them reaching their full potential in further and higher education; gaining employment; and receiving equal pay. Research by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation has found that the scope and level of aspirations among disabled 16 year olds is similar to those of their nondisabled counterparts. Similar proportions aspired to continuing education, training and work. Earnings expectations were also the same. But by 26, disabled people are nearly four times more likely to be out of work, while those in work earn 11% less than non-disabled counterparts with the same level of qualifications. And despite the optimism at 16 years, disabled people are already twice as likely not to be in education or employment at this age than their non-disabled counterparts. Action must be taken to address the unacceptably poor outcomes for young disabled people. There must also be improvements to the key transition phase as young disabled people move on to receiving adult support, so that the same educational and training opportunities exist for disabled learners in further and higher education as for non-disabled learners. 19 Disability equality in schools To ensure disabled children have the same chance to reach their education potential as non-disabled children, there should be: A stronger duty on LEAs to provide a place in a mainstream school or access to special schooling whenever requested. Currently parents and disabled or SEN children are let down both by being forced to take a place in a mainstream school when that is not their wish, or a special school when their preference is for a mainstream placement. While there is a need to increase inclusive schooling, it would be illiberal to force all disabled children to attend a mainstream school, especially as currently some mainstream schools are not providing the quality of education for disabled and SEN children that should be expected. We need to deliver both quality and choice and this is likely to require a less rigid approach to how this is provided. Much greater partnership between mainstream and special schools in a locality is needed to maximise the benefits of inclusion in mainstream schooling and the quality and expertise of special schools. Monitoring of Section 316 should also be carried out to ensure it is not being used as a loophole to avoid duties to provide mainstream placements. A stronger duty on Trust Schools to accept disabled children With the increase in Trust Schools and their greater specialisation, more schools in an LEA area will need to be accessible to ensure that disabled children have the same choices as non-disabled children. A right to independent advocacy to help parents and their children make decision on the best provision in their individual case This may best be provided through the proposed Centres of Independent Living, which should exist in all local authority areas by 2010. CILs can provide expert advice for parents and can help ensure that the wishes of the child are understood and taken into consideration in agreeing decisions on a child’s schooling. Whilst the inclusion of more disabled children in mainstream education will greatly improve disability understanding amongst all pupils, it is also important that children learn about disability and that teachers do no treat disabled children in a discriminatory way. This should be addressed by: Making disability equality a part of the citizenship curriculum Negative attitudes towards disabled people still pervade our society. Disability can be hard to understand for children and young people. Disability equality education within the citizenship curriculum can help to address these negative attitudes. 20 Including disability equality in teacher training programmes. Many teachers themselves report that they feel ill-equipped to teach SEN and disabled children, with a TES survey showing a third of teachers had no disability equality training on their teacher training course and a further quarter only receiving a day’s training or less. Such training should also be included in the training that Liberal Democrats have called for preschool teachers to receive. Meeting the needs of Disabled and SEN pupils Nearly 20% of pupils are categorized as having some sort of SEN and nearly 3% of pupils have had SEN statements. Around three-quarters of children with new statements are placed in mainstream schools. There are high levels of parental dissatisfaction with the current approach to SEN pupils and statementing. Some parents have found local authorities unwilling to make statements, while other have been forced into placement decisions against their wishes. There is a lack of consistency across the country in the quality of how SEN statements are made and the outcomes that result; and a possible conflict of interests that should be investigated as assessments are not carried out independently of LEAs. Some of these problems are related to a schools system that has become focussed on assessment and attainment, rather than raising standards by improving the quality of provision and focussing on pupils individual needs. This is further borne out in research by the Sutton Trust, which found that the top 200 performing non-selective state schools take far below their fair share of SEN pupils. A change of approach is needed that would: Radically overhaul the SEN system to one in which the every child has an assessment of their individual learning needs, with clear best practice guidance Only around 15% of SEN pupils are statemented. Moving towards a system where every child has an assessment of their learning needs would ensure all SEN pupils’ needs are adequately addressed. The group that are currently statemented would be likely to receive the most complex assessments and need the most regular reviews, but assessing all pupils will help schools determine their overall needs and improve their strategy to meeting the needs of disabled and SEN pupils. 21 Link funding to assessments of learning needs, rather than funding schools on simple headcount that assumes the cost of education every child is identical, regardless of whether they are disabled or have SEN Weighted funding according to the assessment of children’s particular needs would ensure that all schools have the necessary resources to provide the support and carry out the reasonable adjustments required by the DDA that the individuals they are educating require. It would support opportunities for more disabled and SEN pupils to attend mainstream schooling. Ensure there are sufficient statutory requirements on Academies and Trust Schools to take disabled and SEN pupils and to work with other schools to meet such pupils’ needs. Academies are able to refuse to take SEN pupils and the future spread of Trust Schools is in danger of further restricting choice and access for disabled and SEN pupils relative to other pupils. It is particularly important that placement decisions are not restricted to simply which school a child attends and whether that is a special school or a mainstream school. For many pupils the answer may be to spend time attending both. There is no evidence that delaying the start of formal learning for those who may be ready at 5 years is damaging to their long term educational attainment. There is growing evidence that starting formal education too early damages many children who are not ready. It has been linked to behavioural problems and low aspirations that may continue throughout a child’s schooling. It may worsen some of the conditions covered by the current definition of SEN, such as social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. It is worth considering delaying the start of formal education until children are 7 years old as is already the case in several European countries. This would not mean delaying the start of learning. Structured and play-based exploratory learning progresses fundamental skills that in some cases may be underdeveloped if formal learning starts too soon. A more favourable environment that improves the long term educational attainment of both disabled and non-disabled children and their well-being could be achieved by: Reducing primary class sizes This existing Liberal Democrat policy, while intended to benefit all pupils, would allow primary teachers to provide the level of attention necessary to improve opportunities for pupils with SENs to be educated alongside their peers. This would increase inclusion; improve the opportunities for pupils with SENs to remain in mainstream schooling throughout their education; and improve disability equality understanding in non-disabled children. 22 Further and higher education and the transition to adult life The Adult Learning Inspectorate has been very critical of Further Education and Higher Education opportunities for disabled people, suggesting there is too little specialist assessment and guidance available across all types of provision. Improvements could be achieved by: A national strategy to provide equitable and easily understood system for planning, funding and placement of disabled and SEN learners The report of the Steering Group of the Learning and Skills Council has recommended that a national strategy is needed to coordinate the regional and local delivery of further and higher education. This would ensure consistent regional provision of high quality post-16 education and training centred on the needs of disabled and SEN learners. While diversity of courses is a strength, the resulting diversity of funding streams needs to be simplified to aid access. Centres for Independent Living having a role assisting learners in their transition and brokering provision of further and higher education within the locality or region The Adult Learning Institute suggested a regional network of Independent Assessment Centres to carry out this role. CILs may be better placed to carry out this role more effectively and at lower cost. They would already be doing much of the work that the Inspectorate highlighted in bringing clarity to multi-agency arrangements so that education and training providers can coordinate provision of services to an individual with their other needs. CILs should already have links with LEAs that could improve the planning of transitions into post-16 education. Provide diverse course structures with modular programmes to build up to qualifications over times scales that meet individual needs It is already Liberal Democrat policy to allow students to combine academic and vocational training through modular course structures in higher education, which would also allow greater flexibility in when and where studying takes place. The flexibility this allows is particularly suited to the needs of may disabled and SEN learners, whose pace of learning, or fluctuating health may require breaks from study. All post-16 learners would be able to work at their own pace towards the eventual attainment of a higher education qualification. 23 Employment and equality While three-quarters of non-disabled working age people are in work, only a third of their disabled counterparts are employed. Around 2.7million of the unemployed disabled people are receiving Incapacity Benefits (IBs). Of these around a million say they wish to work. With greater disability equality in our education system, our benefits system and from employers, it is likely even more would be confident about the idea of working. The structure and reform of the benefits system is a key issue to be addressed by the policy working group on Poverty and Inequality, which is due to report to the Autumn Federal Conference in 2007. It would therefore be inappropriate in this paper to propose in detail reforms in this area. What follows here are some specific reforms to benefits system as it affects particular groups of disabled people, as well as proposals to improve the structure and operation of the Personal Capacity Assessment and welfare-towork programmes as they affect disabled people. Extra support benefits The benefits system serves two clear and distinct purposes. The first is to compensate people for lost income, so that no one is without a means to support themselves during a period of unemployment. The second purpose is to meet the extra costs many disabled people experience in trying to live as independently as other citizens. Incapacity Benefit seeks to perform both functions. On the one hand it exists to replace the income lost when someone is out of work for reason of sickness of disability. On the other, it is higher than Job Seekers Allowance because individuals concerned face higher costs and may be on the benefit for some time (although there is no equivalent rate for long-term JSA recipients). This extra support for disabled people is explicitly linked to their being out of work, rather than on achieving equal citizenship and independent living. At the same time, the benefits that are meant to meet the extra costs of disability are failing to do so, as has been found by a review of research conducted by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP Working Paper 19). The effectiveness of extra supports benefits could be improved by: Including a new category of communication needs in Disability Living Allowance Communication support for some disabled people is a very clear need and fundamental requirement for equality and independent Living. Lack of 24 support for communication needs leads to social exclusion of disabled people and the lack of social confidence and independence contributes to low economic activity of disabled people. Extending entitlement to the higher rate of the DLA mobility component to people who are registered blind. Assessments for the mobility component are mostly based on physical impairments that make it difficult for a person to walk. The exclusion of those whose ability to move around independently is limited due to sight loss is unfair. The higher rate would allow greater opportunity to address this through the use of private transport, taxis and guides. The government has costed the change at £61 million. Address age discrimination in the benefit system People who become disabled after 65 are entitled to Attendance Allowance, which provides extra support for similar needs to those covered by the care component of Disability Living Allowance. However, there is no entitlement to any support for those with mobility impairments. While the cost of an immediate removal of the age based barrier which prevents access to mobility support for those over 65 is prohibitive at around £3 billion, dealing with this bizarre and inconsistent position should be part of a long-term review of the benefit system. Employment support and employment market Job retention Most claimants of incapacity benefits who have were previously in a job expect to return to work. But the longer they remain on IB, the less likely this is to happen. A strategy is needed to prevent so many people losing their jobs when they become sick or disabled. An effective strategy would include: Consultation on introducing a right to Rehabilitation Leave Too many people who are in work go onto benefits after acquiring an impairment and their chances of finding work are substantially reduced. It is thought that taking time off work to learn to deal with a disability would be a ‘reasonable adjustment’ as required by the Disability Discrimination Act, though this has not been tested in the courts. Formalising this as an entitlement to rehabilitation leave, allowing both the employer and employee to adjust to the disability and make adjustments to allow them to remain in work, would be clearer and simpler. Consultation with business, especially smaller firms, would be needed to frame the precise terms of the proposed entitlement and ensure that costs to business are kept to a minimum. 25 Extend Access to the Condition Management Programme (CMP) to those on sick pay or rehabilitation leave CMP has been a successful part of Pathways to Work, the programme to assist incapacity benefit claimants back to work. It should be used to help people before they become claimants, so that it helps prevent them losing their job in the first place. Separation of benefit processing from employment support Job Centre Plus currently has a dual role in both making decisions on benefit entitlement and in providing job seeking and employment preparation support. This requires staff to be skilled in both roles and there is a conflict between their gatekeeper role for access to benefits and their role in supporting people towards employment. The DWP also has a role in both providing services, through Job Centre Plus, at the same time as regulating standards. Since 1998 these roles have been entirely separated in Australia. The publicly funded job brokerage service was replaced by Job Network, a national network of private, voluntary and public organisations. This separated the government role as purchaser and regulator of services from the role of public sector organisations as direct providers. Under the new structure the cost per employment outcome has roughly halved and job seeker outcomes have significantly improved. To achieve similar benefits in Britain, the following changes are needed: Job Centre Plus to be reformed as a purchasing and regulating body with regional and local presence and a gateway to income replacement benefits and employment services Job Centre Plus staff lack the expertise that can be found in the voluntary and private sector, having usually had no more than 12 weeks training. Benefit decisions could be processed more efficiently and the separate regulatory role would provide a much more effective system for ensuring standards of service among the network of providers. The government has recognised the advantage of using private and voluntary sector providers in the roll-out of Pathways to Work – these proposals would allow all providers of welfare-to-work support to be treated equally. Employment and job search support to be procured from a range of public, voluntary and private providers and partnerships based on clearly defined objectives with stable contracts and funding Many of the most successful employment programmes are already run outside of Job Centre Plus. They are able to provide greater expertise and specialised support. As the staff do not have the power to stop benefit payments if a claimant ‘says the wrong thing’, programme participants can develop much more open, honest and productive relationships with advisers. An end to short term contracting and funding 26 will be vital if the organisation providing the services are to undertake the long term investment and planning necessary for success. Support programmes to meet all requirements The support provided to claimants of incapacity benefits needs to meet the complex and diverse requirements of claimants. Key requirements to meeting the needs of claimants are: Reform of the Personal Capacity Assessment (PCA) focussed on providing individual action plans and improved understanding of disability, and in particular mental health problems The PCA is currently under review by two working groups, one of which is focussing on the needs of people with mental health problems. The assessment should be focussed on determining the types of work each individual has the capacity for and the package of support they need to prepare them for work and improve their chances of gaining employment. This assessment must take much better account of mental health problems, multiple problems and fluctuating conditions than the current PCA. Investment to ensure access to health management, work experience, training and employability programmes The government has recognised the benefit of this range of activities in its welfare reform plans. However, there is a lack of commitment to ensuring the capacity that will guarantee access to all who need them. For example, the Condition Management Programme is one of the most successful and popular components of the Pathways to work choices package. However there are not enough specialist health therapists to deliver the programme nationwide to all who would benefit. The shortage is particularly severe for mental health problems. The mental health charity, Mind, has estimated that up to 6,700 new Cognitive Behaviour Therapists and clinical psychologists may be needed to provide access to CMP to all claimants with mental health problems. The training time for these professionals is around 5 years. Reform of Access to Work so that decisions are made for individuals when seeking work, rather than for a specific job once it has been offered The Access to Work scheme, which provides grants for workplace adjustments for disabled employees, is one of the government’s best kept secrets. For every person currently helped through Access to Work there is, on the government’s own figures, a £1,400 net benefit to the Exchequer and a £3,000 net benefit to the economy. Yet it fails to adequately publicise the scheme, so around 80% of SME employers are still not aware of it. Making decisions for individuals would improve their employability and increase take-up of the scheme. 27 Support for employers The government approach to welfare reform has paid almost no regard to employers. Preparing disabled people for work is not enough, if employers do not have the confidence to offer them jobs. The following steps are needed to ensure employers are willing to treat disabled people equally: Promote use of Access to Work with employers As mentioned above, about 80% of SMEs have not heard of Access to Work. Even if it is made more effective through entitlement being attached to individuals seeking work, lack of awareness amongst employers should still be addressed by properly publicising the scheme to tackle the negative assumptions employers make about the costs they might face if they employ disabled people. Partnership with employment support providers The most successful employment support programmes are those that work in partnership with employers. It helps improve the attitudes of employers towards disabled people and gives disabled people the opportunity to show what they are capable of. Promote disability confident businesses There are many benefits that disabled people can bring to businesses. Over a third of UK businesses have hard to fill vacancies, yet 3.4 million disabled people are out of work. At least 1.5 million part time disabled workers work below their skills potential. 82% of disabled customers say they have taken their business to a more disability confident competitor. The government should work in partnership with businesses on a high profile campaign to promote disability equality to employers and make them aware of the benefits to their business of becoming disability confident. Government must lead by example Government departments and the public sector should be employing more disabled people. Even the Department of Work and Pensions own staff base consists of just 5.25% disabled people, compared to 13% of the workforce. Both government departments and its agencies should have strategies for increasing the number of disabled people they employ. Ring-fenced funding for making workplace adjustments is necessary to ensure disabled candidates are not prejudiced against. The government’s moves to require government departments to use their own funds instead of Access to Work, for making adjustments are therefore a dangerously regressive move. 28 Home and family life In moving away from a paternalistic care based approach to disabled people, it is important to ensure that disabled people have the same opportunities as nondisabled people to have fulfilling leisure lives, emotional and sexual relationships, and to start their own families. Housing Disabled people want to have greater choice about where they live and who they live with. The lack of accessible housing is a key reason behind this lack of choice, which is also a lack of equality with non-disabled people. The removal of means testing for qualification the Disabled Facilities Grant for families with disabled children s a welcome step. We would welcome a future review of means testing for other DFG recipients. The following changes will also help address this inequality: Incorporation of the Lifetime Homes Standard (LHS) into building regulations A survey of physically disabled people found 40% of them found that their housing situation made them unnecessarily dependent on others. LHS features 16 design standards which help ensure that the house is accessible and easily adaptable to meet future needs, helping more disabled people to gain independence. This would require changes to part M of the buildings regulations, so should be consulted on and subject to a regulatory impact assessment. A requirement for local authorities to maintain an accessible housing register Without the records such registers hold, adaptations fail to be reused with subsequent occupants, particularly in private sector housing. Where they are already being used (e.g. Liverpool, Glasgow, Reading) it has achieved more efficient use of accessible properties. Whist there is a cost to local authorities in maintaining such registers, savings in care costs follow from more disabled people living in suitable adapted accommodation. An enhanced duty on councils to ensure sufficient provision of accessible housing Even LHS homes are not ‘liveable’ for wheelchair users without further adaptations. Local authorities need a duty to ensure sufficient quality and quantity of different types of accessible housing to meet the range of disability requirements. Given the current shortage this will take time, but targets should be set so that opportunities to expand the accessible housing stock are maximised. 29 New powers to ensure disabled people can be housed in localities with best access to transport and services for disabled people While access to transport and services is vital for disable people, it is housing with the most convenient access to transport and services that tends to be most highly valued in the market place and most attractive to commercial developers. There is a shortage of housing that is both accessible for occupation and located in an area with accessible services. Powers for councils to designate areas where developers are required to provide a minimum proportion of accessible housing, with priority access for disabled people, should be considered. Transport Rail The Disability Discrimination Act has introduced welcome duties in regard to wheelchair users, ensuring that new rolling stock is accessible and there are deadlines for improving the accessibility of the full fleet. However, there are still areas of rail travel that should be addressed, including: Extending DDA duties to cover scooters Most rail operators refuse to allow access to scooters and the DDA has no requirements in regard to this type of mobility vehicle user. There is a significant range in the size and weight of scooters used that present challenges that may not be easy to surmount for some models. However, DDA requirements for rail operators should be reviewed in consultation with scooter manufacturers and the rail industry with a view to extending duties to users of as many types of scooters as possible, with point of sale information on those scooters which can access trains. Disability equality training for station staff Although accessibility for rail travel is improving, many disabled users still find it difficult to receive support from station staff when booking journeys or when arriving at stations and boarding or exiting trains. Air and Sea Travel The agreement in the European Parliament on new laws to outlaw refusal of booking and boarding for disabled people on flights is welcome. The new rules must ensure: Disabled people cannot be refused booking or boarding on flights due to an impairment Disabled people are not charged extra for the flight or for any necessary assistance in the airport There is a statutory duty to provide, where necessary, assistance to disabled people from arrival at an airport to boarding their plane, or continuing their journey after their flights arrival 30 Provision of flight information in accessible forms at airports and from travel operators Any attempt to dilute these rules, either in the Council of Ministers or when being transposed into EU law, should be opposed. Agreement should also be sought by the UK and EU on similar standards beyond the EU. Extend Disability Discrimination Act requirements to passenger sea craft International agreements must also be sought on how similar accessibility requirements to those in the Disability Discrimination Act for other forms of transport can be extended to water craft. Driving Driving is a vital way of getting round for many disabled people, giving them freedom they would otherwise not have. However, with more drives on the streets and increasing congestion, getting around and getting access to services in cars becomes increasing challenging. Improvement could be made by: Addressing the abuse of disabled parking facilities Whilst abuse of disabled spaces on highways and in local authority run parking can be tackled by parking attendants, in many private car parks, such as those at supermarkets, there is often no attempt to tackle such abuse. An RAC survey found that 14% of non-disabled drivers admit to using disabled parking bays. With the growth in out-of town shopping, disabled people say this has become a serious problem. Investigation is needed into the extent and impact of this abuse, followed by consultation on ways in which it might be addressed, ranging from voluntary schemes, such as those run by some supermarkets who impose fines, to statutory duties on service providers to manage and maintain off-street parking to a minimum standard. Protect disabled drivers from the impact of congestion charges and road-user charges The move towards greater use of congestion charging and road user charging is an essential part of tacking congestion and climate change. Improving congestion will help many disabled people who rely on driving. However, despite improvements to public transport through the Disability Discrimination Act, many disabled people do not have the same opportunities as non-disabled drivers to leave their car at home. The needs of Blue Badge holders should be taken into account in the design of future congestion charging and road-user charging schemes. Extend parking fines to drivers who block accessible features of the built environment While progress continues to be made in ensuring that the built environment is more accessible, the increasing number of drivers means 31 that more and more cars are parked blocking accessible features such as slopes, ramps and tactile pavements. The immediate redress of parking fines would be the best way to stamp out this problem, making blocking an accessibility feature a ticketable offence. Buses Access to buses is also improving thanks to the Disability Discrimination Act. Supply of accessible buses is still very variable. For example, most of London’s bus fleet is now accessible, but in many rural areas there are still very few accessible vehicles in operation. The DDA should ensure this will improve over time. But the experiences of disabled people where accessible fleets are in operation suggest there remain two key problems that need addressing: Action to ensure provision of accessible buses on designated accessible routes Many disabled people report that bus companies are flouting requirement to provide accessible buses on designated accessible routes. There are anecdotal reports of drivers leaving disabled passengers stranded on the pavement instead of taking the time to lower the ramp and provide support for them boarding a bus. The requirements to run accessible routes must be more effectively monitored and enforced. Preventing non-disabled people blocking access to designated seating for disabled people Disabled people frequently report that they are left without a seat because designated disabled seating is taken up by other passengers. This is not an area where legislation could help, but there are initiatives that bus companies should take forward to help prevent this happening by increasing the disability awareness of their non-disabled passengers. Accessible seating could also be much more clearly marked. Carers There are six million carers in the UK. These are the family and friends of disabled people and the care that they provide is estimated to be worth £57 billion per year. Recent legislation has brought welcome improvements to carers rights, such as the right to request flexible working and new rights in relation to carers’ assessments and the consideration that must be given to a carers’ own work, education and leisure wishes. However many carers still face significant poverty, particularly if they are caring full time and dependent on Carers’ Allowance. The following options could help address carers’ poverty and welfare: A right to access employment support programmes Under the government’s welfare reform plans a person receiving carers’ allowance may be entitled to less employment support than the person who they care for who receives IB. Given that carers have a new right under the Carers (Equal Opportunities Act) for their employment wishes 32 to be taken into account when they receive a Carers Assessment, those in receipt of Carers’ Allowance should be able to access employment support. This may be particularly important for those who have been carers since childhood and have never worked. Ending the 21 hour study rule on carers People who study for more than 21 hours a week are excluded from entitlement to carers allowance. Although full-time students have access to other funds, it involves getting into debt, which is more off-putting for carers than others who want to study as their caring role may limit their earning potential and ability to pay off their debts after studying. Students who are carers also face greater costs than other students from their caring role. The effect of this rule is to discriminate against carers and deny them the same educational opportunities as others. Working tax credit for carers available at 16 hours per week Working tax credit is already for working parents and disabled workers who work for 16 hours a week or more – the general rule is 30 hours per week. Extending the entitlement to carers working 16 hours a week or more would recognise that carers too have restrictions on the length of time they are able to spend in paid employment relative to other workers. A citizens pension Improvements to the party’s citizen’s pension policy have already been proposed so that there would be a universal, non-contributory, Citizen’s Pension set at a level to keep people out of poverty. This would be of particular benefit to many carers who have been unable to make significant contributions towards the state pension of an occupational of private pension as the time spent caring has kept them out of work. Better provision of respite breaks 4 out of 5 carers have to cut out on holidays and 3 out of 4 cut back on leisure activities. Those carers who do not get breaks are twice as likely to suffer from mental health problems. Carers assessments should take into account the need for respite breaks and this should result in the provision of whatever support is necessary to ensure that breaks can be taken. Relationships Prejudice and other barriers that prevent independent living also stand in the way of the opportunity for disabled people to find a partner, form intimate relationships and start families. While moves towards achieving greater independent living generally will greatly assist disabled people in having more opportunities to develop friendships and intimate relationships, other moves that would help are: 33 Disability equality training for family planning professionals Disabled people seeking help through the usual routes (GPs, NHS clinics) find almost no consideration is given to their particular needs. There should be a level of core skills for family planning professionals working in the NHS in understanding the particular requirements of disabled people, with access to professionals with specialist knowledge of disability for those who need it. Leisure and social lives Leisure activity is important to everyone’s health, well-being and enjoyment of life. The duties for service providers in the Disability Discrimination Act are improving access to leisure for many disabled people. Disabled people want more than organised leisure activities; they want more inclusive leisure with greater freedom to choose who they spend leisure time with and which interests they pursue. Inclusive leisure is therefore mainly be supported by other parts of the independent living agenda that increase the opportunities to spend time in the same environments where non-disabled people form friendships and make plans for social activities, including: Increased access to mainstream schools Greater participation in work More choice in where to live and who to live with The importance of our proposals above on these points is given greater weight by their role in allowing inclusive leisure and social lives. There are also some changes that would benefit particular groups of disabled people: Disability equality training for customer facing staff in the leisure sector The main type of complaint from disabled people accessing leisure services concerns failures of staff to appreciate and support their needs. The low pay, temporary nature and high turn over of staff in many leisure venues can be a challenge to ensuring staff are trained in disability equality. Even a small amount of training to ensure that staff are aware that they should be alert to the needs of disabled people could go a long way as disabled people can frequently give a lead to a member of staff if they are is prepared to listen and willing to assist. Increase in the amount of audio description television programmes Currently there is a subtitling target of 80% for televisions programmes, but the target for audio description for the blind and partially sighted is just 10%. This should be increased to 20% as soon as possible and the target should be kept under review with a view to further future increases. 34