Swainson’s Warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii )

Management/Conservation Profile

By John A. Gerwin, Curator of Birds, 2006

North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences

BBS distribution and

abundance

Photo by Laurie S. Johnson

© 2005 NatureServe, 1101 Wilson Boulevard,

15th Floor, Arlington Virginia 22209, U.S.A.

All Rights Reserved.

The Swainson’s Warbler, Limnothlypis swainsonii, has been described as one of the most secretive and least

known warblers in North America. Audubon formally described it in 1834. This species is a member of the

wood-warbler group, or family Parulidae. The genus name is Latin for “marsh finch” (limne, “a marsh”;

thlypis, “a kind of finch”). The species name, swainsonii, is in honor of William Swainson, a widely

traveled and versatile naturalist from England. This warbler is of high conservation importance, because of

its small breeding range, specialized habitat requirements, low overall densities, and even more restricted

winter distribution.

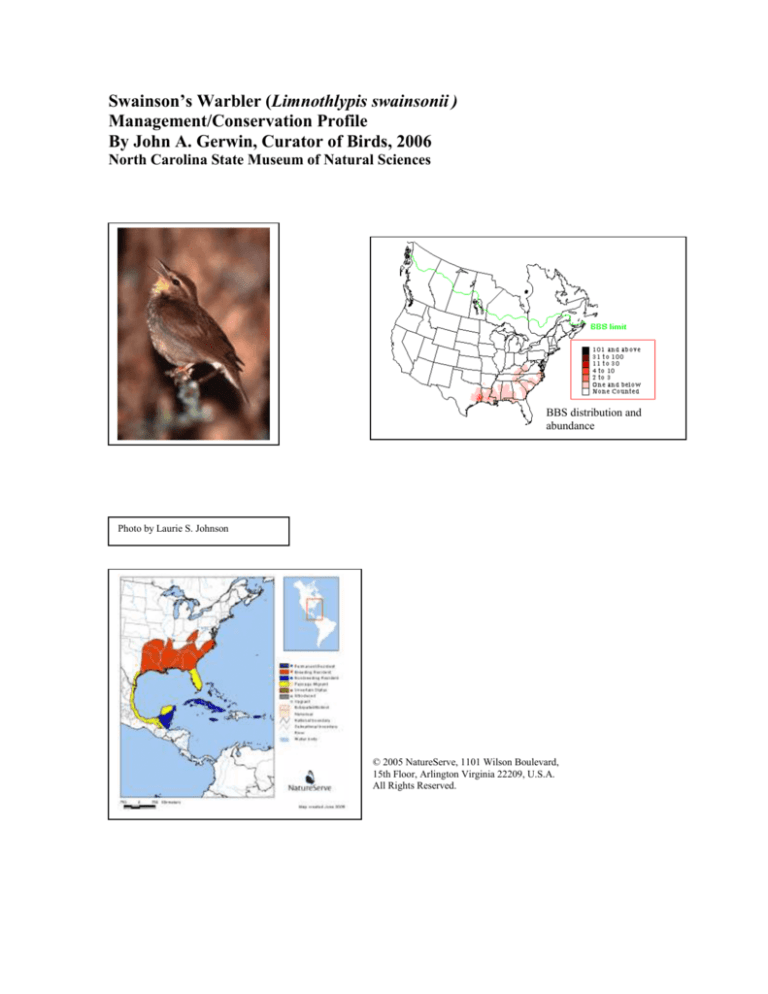

Description

The upperparts appear as a medium brown, although up close they are an olive-brown. The cap is russet,

which is more intense in adults. The supercilium is dull whitish. The underparts are generally a dull whitish

color, with variable amounts of grayish-brown smudging in the lateral chest area and yellowish “washing”

throughout. The amount of yellow wash varies – adult birds are noticeably “whiter” due to feather wear,

from mid June to mid August. Hatch year birds in first basic plumage show a strong yellowish wash. The

bill is large and stout, relative to the birds’ overall size (~5 inches/12.5 cm). The sexes are similar in

appearance.

Range

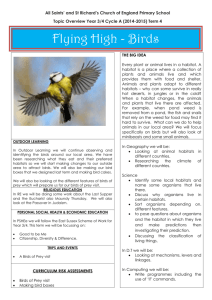

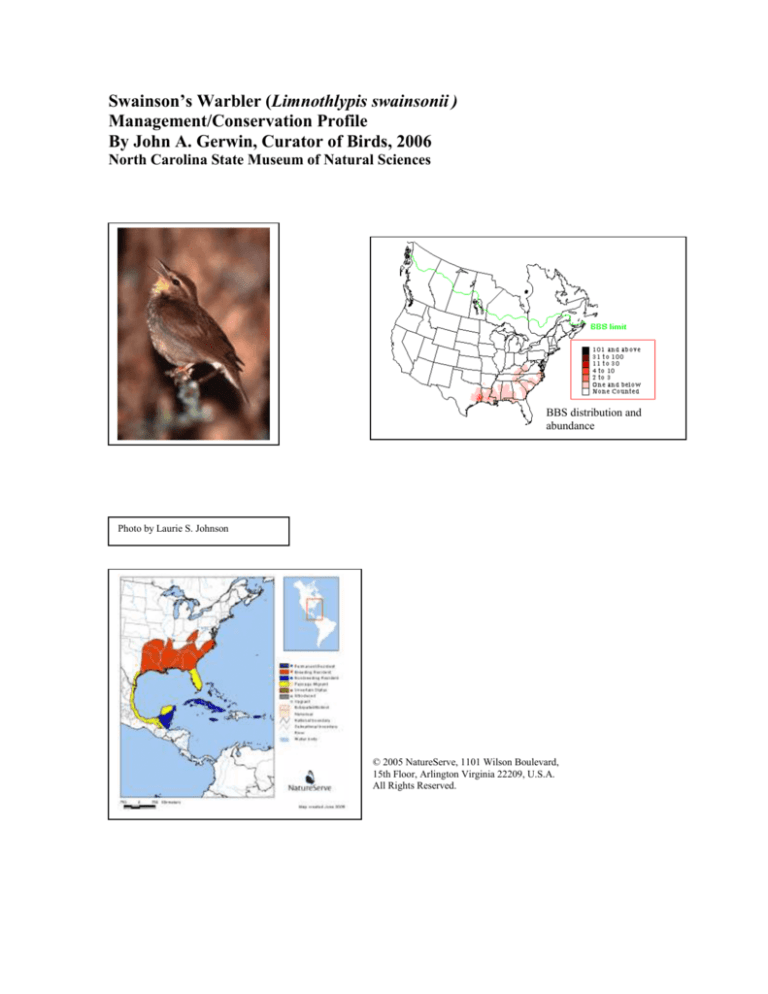

The Swainson’s Warbler is a Neotropical migrant that breeds in appropriate habitat in the southeastern

United States (see BBS and NatureServe distribution maps). In North Carolina, it breeds throughout the

Coastal Plain and along the eastern escarpment of the Blue Ridge, but is typically absent from the upper

elevations of the mountains (>3,000 ft). It has been found rarely in some Piedmont locations, but is a regular

inhabitant of pocosin habitat in the Sandhills region. This species spends the non-breeding portion of its

annual life cycle among several Caribbean islands (e.g. Bahamas, Jamaica, Cuba, Hispaniola), and is also

known from the Yucatan region, and parts of Belize and Honduras.

Status

The Swainson’s Warbler is currently assigned a Global Conservation Status Rank of “G4”, [Apparently

Secure — Uncommon but not rare; some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.].

Breeding Bird Survey data (1966-2002) indicate increasing numbers when analyzed over the species entire

range (~+8%/year). In North Carolina, BBS data indicate a slight overall decline (-0.26%/year). Areas in the

NE and SE coastal plain showed annual declines of 1-2%, whereas in the Blue Ridge physiographic

province, the data indicate a sharper decline, at –11%/year. But note that this species is poorly surveyed via

the BBS method. In North Carolina, where ~80 routes are conducted, data exist for 19 routes, with an

average of one bird detected/four routes. In the Blue Ridge, birds were detected on only seven routes. Over

the species range, the detection rates average 0.16 birds/route.

Habits

This species is shy, skulking, and seldom seen without the use of song playback. The loud, clear, ringing

song is ventriloquistic, making the source difficult to locate. Males tend to sing from four to 12 meters high,

but will also often sing from the ground while foraging.

Swainson’s warblers forage almost exclusively on the ground, among dead leaf litter. Birds walk along and

use their stout beaks to flip leaves over, searching for invertebrates. During severe flood events some birds

will forage in vines and live leaves, 1-2 m above the ground. Few diet studies have been done. These

warblers are reported to eat beetles, ants, spiders, crickets, caterpillars, and other invertebrates in lesser

proportions. In the non-breeding season, birds in Jamaica were studied and found to consume beetles (39%),

spiders (22%), and ants (19%). More than 60% of the regurgitation samples from Swainson's Warblers

contained orthopterans and/or gecko (Sphaerodactylus goniorhynchus) bones.

This species occurs in low densities in mature bottomland hardwood forests, where pairs are typically found

near vine thickets and cane patches created by treefalls and subsequent light gaps. In some heavily managed

areas, the species has been found in rather high densities, where conditions have led to heavy vine and cane

reproduction. It has been suggested that this species may be “semi-colonial”, but distinct territories are

maintained. Telemetry, tape playback, and banding studies indicate birds move widely, and may occupy

territories as divergent as 3-18 hectares (7-44 acres) in size. At one focal study site in regenerating forest in

SC, territories ranged from 4-10 ha. Thus, a reasonable population density estimate would be 5-10 pairs/km2.

At sites in SE Louisiana, densities in optimum pine and hardwood habitats were 10 and 12 pairs per km2,

respectively. Most nests are 0.5-3m above ground, with a few as high as 5m. Nests are built in young cane,

palmettos, edges of vine tangles, or in small saplings/shrubs. At the SC site, pairs were regularly observed to

nest multiple times within a season. Ten percent of 99 nests monitored were parasitized by Brown-headed

cowbirds.

At this same study site near Myrtle Beach, SC, many males were back on territory by mid April, with some

females on site by the third week (1996-2005). Here, nest initiation typically begins in early May. Along the

Roanoke River near Windsor, birds are typically detected and “on territory” by the last week of April.

Habitat

The Swainson’s Warbler inhabits rich, damp, deciduous floodplain and swamp forests, and requires areas

with deep shade from both canopy and understory cover. On the coastal plain, it occurs in areas with dense

upper and midstory canopies and shrubs, and little herbaceous cover. A significant component of territories

in SC and VA included the extent of disturbance gaps and concomitant vine tangles (“understory thickets”),

with Switchcane patches (Arundinaria gigantea) at the SC site. Vine tangles were comprised of the

following species, usually a mix of more than one: grapes (Vitus sp.), Cross Vine (Bignonia, or Anisostichus

capreolata), Poison Ivy (Rhus radicans), greenbriars (Smilax sp.), Trumpet Creeper (Campsis radicans),

Rattan, or Pepper Vine (Ampelopsis arborea), Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), Supplejack

(Berchemia scandens) and Blackberry (Rubus sp.). Of all the vines, grapes and greenbriars were most often

used as a nesting substrate. Similar characteristics were noted from a Virginia study.

Although Switchcane does not appear to be a necessary component of territories, several studies have found a

positive correlation between its occurrence and breeding success (Missouri, Illinois, Georgia, and South

Carolina). However, habitat requirements of other significant breeding populations in Georgia and South

Carolina differed. Graves found no cane at a site in Georgia with the highest SWWA population density on

record, and also observed less cane in territories compared to non-use plots in the Great Dismal Swamp. He

also considered greenbriar abundance and the absence of standing water as important to SWWA distribution.

Meanley also identified greenbriar as commonly associated with SWWA. It appears that this species selects

habitat based on the understory structure, whether created by cane, vines, shrubs, saplings, blackberry, or

palmetto.

Hydrology has direct and indirect effects on SWWA distribution. At the SC site, nesting areas were not

subjected to prolonged flooding during the breeding season. In the Great Dismal Swamp, water was absent

from territory plots, but detected on 61% of those plots where SWWA were not found. Hydrophytic species,

such as bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) and water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica), comprised less than 1% of the

trees counted on nesting and territory plots. Hydrology can also affect available leaf litter as the scouring

from a 1998 flood at the SC site demonstrated. Three years after flooding, leaf litter accumulation was

approaching pre-flood conditions. The effects of periodic or prolonged flooding are crucial selective stresses

on the distribution of bottomland hardwood plants, with elevation responsible for the degree of flood

exposure. Areas occupied by SWWA follow a gradient from Zone II through V, with nesting concentrated in

the highest zones of the bottomland. According to plant species, SWWA nests are located on the highest

ground of the bottomland.

In the mountains, moist lower slopes of mountain ravines at elevations to 900 m (~3,000 feet) are preferred,

and a shrub layer of rhododendron-mountain laurel is most common. Where surveys were done in the

Southern Appalachians, individuals were detected primarily in sawtimber and to a lesser extent in pole stands

of second-growth cove forests. A recent study of nest success, in the Jocassee Gorges region of South

Carolina, found this species preferring to nest in young hemlocks. Essentially no published data exist on

SWWA habitat preferences, at the nest or territory scales.

SWWA was found breeding in commercial pine plantations in east Texas in 1996. Very little is known about

the quality of habitat, why it is selected, or how well the birds reproduce and survive. In the Louisiana

studies (1998-2003), those pine habitats occupied by SWWA were characterized by a thick leaf litter layer,

low herbaceous ground cover, a well-developed understory with a high density of small stems, and a closed

canopy. These are all features reported by other researchers from studies in hardwoods. Researchers did

report some slight differences. In pine (vs. her hardwood comparisons), territories generally had a higher

density of nest-mimicking clumps of leaves, blackberry stems were most dense at the nest patch scale, and

palmetto fronds were much higher in the vicinity of nests. Also, the leaf litter layer was less deep than in

random sites. The structural attributes of a leaf layer composed primary of pine needles may create a

substrate that, when to thick, is not necessarily better for foraging. Thus, the presence of hardwood species

within pine forests may influence the suitability of the foraging substrate, and thus, whether or not birds settle

there.

Management Recommendations

Land managers can initially assess the likelihood of this species occurrence on their lands by looking at

range and habitat associations. This species should be surveyed for with the use of tape playback. Daily

singing is episodic and occurs up to dusk. Note that many individuals respond with only chip notes, or a

silent approach. Chip notes as well as songs should be broadcast. Recordings are available from the

sound labs at Cornell or Ohio State universities, as well as from commercial “Birding by Ear” tapes and

CD’s. In North Carolina, coastal plain birds should be surveyed between May 1 – June 15. Males’

singing rate and response to playback drops significantly toward the latter part of this period, or just

afterwards, when young from the first broods are fledging. In the mountains, this same period should

generally work, although 7 May – 7 June would also be fine.

Studies on the Atlantic and Gulf Coast indicate a preference for early successional forest or disturbance

gaps in primeval (old growth) hardwood forests, but also pine plantations with appropriate qualitites.

There are, of course, different methods available to create such habitat types. The comments below

relate only to Coastal Plain regions, including pine; few data exist for SWWA habitat preferences in the

Blue Ridge physiographic province. In addition, these ideas are most appropriate in the higher zones of

riverine areas. Hydrology, floristics, and disturbance regime all interact to influence SWWA habitat

preferences, rather than a single habitat attribute. Areas subjected to prolonged flooding during the

spring months do not attract Swainson’s warblers, in general. Leaf litter accumulation is a vital habitat

component for Swainson’s Warbler foraging and nesting success. One study showed that occasional

scouring (one/5 years) from flood events did not adversely affect the population. Note that this species

has been found in low densities in mature forest where small gaps were created (usually by weather or

flooding events), and territory size estimates were quite high. This is considered “natural” or “normal”.

In other studies in younger stands, the species occurred in higher densities, with some birds occupying

smaller territories.

1.

A manager could designate an area of mature bottomland forest (60+ years) and use an

uneven-aged silvicultural system with small (<4 ha/10 ac) group selection cuts. These group

selection cuts mimic tree fall gaps, which would stimulate cane and vine thicket regeneration

and maintenance within a matrix of mature forest. The creation of small gaps in this manner

will result in a higher edge/area ratio, which may attract cowbirds (depending upon landscape

context, e.g. proximity to agricultural operations). In areas where the overall landscape is

already fragmented by other factors, even though a relatively small amount of edge is created,

this method may not be desirable. One study summarized data for ~1400 nest attempts by

open-cup nesting species in the Southeast, and they found an overall 10% parasitism rate by

cowbirds. Most researchers agree this is a ‘tolerable’ rate, but that it may also be an upper

limit for some species.

2.

Another option is to use clearcutting in an even-aged silvicultural system to manage for

SWWA, and harvest larger areas (e.g. 10-20 ha blocks), with a 60-80 year rotation age. When

managed on an area-regulated basis, a constant proportion of the managed area (33-25%,

respectively) would be <20 years old. These areas would be allowed to regenerate naturally

into bottomland hardwoods, and an early successional seral stage would be maintained for

breeding habitat. This may result in a lower edge/area ratio, but a larger absolute amount of

edge, when compared to uneven-aged management.

3.

In pine plantations, there are only short windows of time when the habitat is suitable (pole

stage and mature pine), when companies typically thin or harvest. Delaying mechanical

thinning until the understory diminishes naturally (13-14 years in SE Louisiana) may incur

some cost to timber operations, but would benefit understory nesting birds including SWWA.

4.

Regardless of the stand age, researchers agree that the following characteristics are critical for

Swainson’s Warbler feeding and nesting success:

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

g.

h.

5.

A good accumulation of leaf litter, in areas with sparse herbaceous cover.

The absence, or near-absence, of standing water in territories during the breeding season.

Deep shade, provided by a well-developed midstory and/or overstory.

“Understory thickets” - areas with dense vine tangles, cane patches and/or blackberries.

A well-developed shrub/sapling component (e.g. American and Deciduous hollies [Ilex

opaca/decidua], American Hornbeam [Carpinus caroliniana], Red Maple [Acer rubra],

Hackberry [Celtis laevigata]).

Stem densities of 30,000-50,000 stems/ha appear to provide high quality cover for nesting

and foraging throughout the species range.

Palmetto fronds were strongly selected at the nest patch scale in both pine/hardwood

habitats in Louisiana, and these should be maintained if present.

In pine plantations, allow hardwood species to co-occur, to provide a mix of

pine/hardwood leaf litter, for SWWA foraging.

And finally, the large the area the better. Considering the variability of territory sizes, areas

under consideration should be at least 300 ha.

A.

B.

C.

D.

Vine “tents” and tangles.

Small shaded glades carpeted with leaf litter.

Thickets of shrubs, tree saplings, vines and Rubus spp. associated with canopy gaps.

Giant Cane (Arundinarea gigantea), may or may not be present

SOURCES OF TECHNICAL INFORMATION ON SWAINSON’S WARBLER AND OTHER

BOTTOMLAND HARDWOOD BIRDS FOR LANDOWNERS AND NATURAL RESOURCE

MANAGERS

Annand, E. and F. Thompson, III. 1997. Forest bird response to regeneration practices in central hardwood

forests. Journal of Wildlife Management. 61: 159-171.

Askins, R. 2001. Sustaining biological diversity in early successional communities: the challenge of

managing unpopular habitats. Wild. Soc. Bull. 29: 407-412.

Bassett-Touchell, C. Audra, and P. Stouffer. 2006. Habitat Selection by Swainson’s Warblers Breeding in

Loblolly Pine Plantations in Southeastern Louisiana. Journal of Wildlife Management. 70(4):1013–1019.

Brawn, J., S. Robinson, and F. Thompson III. 2001. The role of disturbance in the ecology and conservation

of birds. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 32: 251-276.

Brown, R.E., and J.G. Dickson. 1994. Swainson's Warbler (LIMNOTHLYPIS SWAINSONII). In A. Poole

and F. Gill, editors, The Birds of North America, No. 126. Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and

American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, DC. 20 pp.

Bushman, E. S., and G. D. Therres. 1988. Habitat management guidelines for forest interior breeding birds of

coastal Maryland. Maryland Dept. Natural Resources, Wildlife Tech. Publ. 88-1. 50 pp.

Carrie, N.R. 1996. Swainson’s warblers nesting in early seral pine forests in east Texas. Wilson Bulletin

108(4): 802-804.

Carter, M., C. Hunter, D. Pashley, and D. Petit. 1998. The Watch List. Bird Conservation, Summer 1998:10.

Dickson, J. G. 1978. Forest bird communities of the bottomland hardwoods, pages 66-73, in Proceedings of

the workshop management of southern forests for nongame birds. USDA Southeastern Forest Experiment

Station General Technical Report SE - 14.

Dickson, J.G. 1978. Forest bird communities of the bottomland hardwoods. Pages 66-73 in R.M. DeGraaf,

ed. Proceedings of the workshop: management of southern forests for

nongame birds. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Atlanta, Georgia. GTR/SE – 14.

Eddleman, W. R., K. E. Evans, and W. H. Elder. 1980. Habitat characteristics and management of

Swainson's warbler in southern Illinois. Wildlife Society Bulletin 8:228-33.

Graves, G. R. 2001. Factors governing the distribution of Swainson's Warbler along a hydrological gradient

in Great Dismal Swamp. Auk 118:650-664.

Graves, G. 2002. Habitat characteristics in the core breeding range of the Swainson’s Warbler. Wilson

Bulletin 114(2): 210-220.

Henry, Donata R. 2004. Reproductive Success and Habitat Selection of Swainson’s Warbler in Managed

Pine versus Bottomland Hardwood Forests. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Ecology and Evolutionary

Biology, Tulane University.

Hooper, R. G. 1978. Cove forests: bird communities and management options. Pages 90-7 in R. M. DeGraaf

(editor). Management of southern forests for nongame birds. U.S. Forest Service General Technical Report

SE-14. Southeastern Forest Experimental Station, Asheville, North Carolina. 176 pp.

Hooper, R. G. and P. B. Hamel. 1979. Swainson's warbler in South Carolina. Pages 178-82 in D. M. Forsythe

and W. B. Ezell, Jr. (editors). Proceed. First. S. Carolina End. Sp. Symposium. S. C. Wildl. and Man. Res.

Dept.

Hunter, C., D. Buehler, R. Canterbury, J. Confer, and P. Hamel. 2001. Conservation of disturbancedependant birds in eastern North America. Wild. Soc. Bull. 29: 440-455.

InfoNatura: Birds, mammals, and amphibians of Latin America [web application]. 2004. Version 4.1.

Arlington, Virginia (USA): NatureServe. Available: http://www.natureserve.org/infonatura. (Accessed:

September 2, 2005).

Lorimer, C. 2001. Historical and ecological roles of disturbance in eastern North American forests: 9,000

years of change. Wild. Soc. Bull. 29: 425-439.

Meanley, B. 1971. Natural history of the Swainson's warbler. U.S. Dept. of Int., Bureau of Sport Fisheries

and Wildlife, North Am. Fauna No. 69. vi + 90 pp.

Peters, K.A., Lancia, R.A., and John A. Gerwin. 2005. Swainson’s Warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii)

habitat selection in a managed bottomland hardwood forest. Journal Wildlife Management: 69(1): 409-417.

Pashley, D.N. and W.C. Barrow. 1993. Effects of land use practices on Neotropical migratory birds in

bottomland hardwood forests. Pp. 315-320 in Status and management of neotropical migratory birds (D.M.

Finch and P.W. Stangel, eds.). U.S. Forest Service Gen. Tech. Report RM-229, Fort Collins, CO.

Robinson, W. and S. Robinson. 1999. Effects of selective logging on forest bird populations in a fragmented

landscape. Conservation Biology 13: 58-66.

Sallabanks, Rex, Jeffrey R. Walters, and Jaime A. Collazo. 2001. Breeding Bird Abundance in Bottomland

Hardwood Forests: Habitat, Edge, and Patch Size Effects. Condor: 102(4): 748-758.

Strong, A.M. 2000. Divergent foraging strategies of two Neotropical migrant warblers: implications for

winter habitat use. The Auk 117(2): 381-392.

Thomas, B.G., Wiggers, E.P., and R.L. Clawson. 1996. Habitat selection and breeding status of Swainson’s

Warblers in southern Missouri. Journal Wildlife Management 60(3): 611-616.

Thompson III, F. and R. DeGraaf. 2001. Conservation approaches for woody, early successional

communities in the eastern United States. Wild. Soc. Bull. 29: 483-494.

Thompson, Jennifer L. 2005. Breeding biology of Swainson’s Warblers in a managed South Carolina

bottomland forest. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Zoology, North Carolina State University. 177 pages.

Wharton, C.H., Kitchens, W.M., Pendleton, E.C., and T.W. Sipe. 1982. The ecology of bottomland

hardwood swamps of the southeast: a community profile (FWS/OBS-81/37). US Fish and Wildlife Service,

Biological Services Program, Washington, DC.

Wright, Elizabeth A. 2002. Breeding Population Density and Habitat Use of Swainson’s Warbler in a

Georgia Floodplain Forest. MS Thesis. The Warnell School of Forest Resources, The University of Georgia

WEBSITES OF INTEREST

http://www.natureserve.org/infonatura/servlet/InfoNatura?searchName=Limnothlypis+swa

insonii

http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/cgi-bin/atlasa02.pl?06830