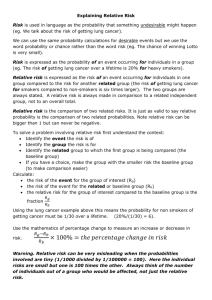

Lung Cancer, No Smoking Reed Pence: The number one cancer

advertisement

Lung Cancer, No Smoking Reed Pence: The number one cancer killer in the world is also, in some ways, remarkably misunderstood. This year, more than 200,000 Americans are expected to be diagnosed with lung cancer, and more than 150,000 are expected to die. For many other cancers, survival rates have risen the last few decades. Not so with lung cancer. Andrea McKee: In the absence of screening or early detection implementation, the overall five year survival for all-comers with lung cancer is about 16% and it really hasn’t changed dramatically over the past several decades, despite some of our improvements in the delivery in care for these patients. Reed Pence: That's Dr. Andrea McKee, Chairman of Radiation Oncology at Leahy Hospital and Medical Center in suburban Boston. Andrea McKee: A lot of it has to do with the fact that in the absence of screening about 70% of patients will be diagnosed with late stage lung cancer at presentation eitherStage Three orStage Four, which is in large part incurable lung cancer. Only about 30% will present with Stage One or Two, which are the more curable stages of the disease. Heather Wakelee: In general we don’t talk about cure very often unless were able to find the disease when it’s very, very small. We call early stages, Stage One or Two. Reed Pence: Medical Oncologist Dr. Heather Wakelee is Associate Professor of Medicine at Stanford University and the Stanford Cancer Institute. Heather Wakelee: When patients are diagnosed with Stage Four lung cancer or metastatic lung cancer, as it’s also called, those are most of the patients I’m seeing as a medical oncologist. And, unfortunately, we don’t really know how to cure people in that setting. That doesn’t mean we can’t help them live with their disease for a period of time and that period of time can be years in many cases. But it’s living with the disease as opposed to being able to say that it’s completely gone. Reed Pence: About 85% of people diagnosed with lung cancer are current or former smokers. The other 15%--more than 30,000 Americans per year--have never smoked. Often non-smokers are diagnosed in later stages of the disease, because no one's expecting it or looking for it. Dr. Joan Schiller is Deputy Director of the Simmons Cancer Center at the UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and President of the advocacy organization Free To Breathe. Joan Shiller: In the United States, about 15% of all lung cancers occur in individuals who have never smoked. And the majority of those individuals do not have a big risk factor for getting lung cancer that we know of such as radon, although radon is a risk factor. In fact that number is going up, lung cancer in never non-smokers is going up, and if we could somehow today eliminate all lung cancers in smokers, the number of lung cancers in never smokers would be higher than the number of deaths due to pancreatic cancer for example or leukemia or AIDS. Lung cancer in never smokers is a real health problem. Andrea McKee: We do see lung cancer in never smokers and we’re not entirely certain as to why we’re seeing this now because we do know that tobacco is an important risk factor for the development of lung cancer. We think it may be a genetic predisposition to the disease, because the cancers that we’re detecting in never smokers actually they look a little bit different both under the microscope and Scio genetically, the genetic profiles of those cancers are a little bit different, and so we tend to treat them a little bit differently. Reed Pence: However, Schiller and Wakelee say most people treat anyone with a lung cancer diagnosis the same--almost as if they deserve to have their disease. Joan Shiller: Whenever anyone tells anyone that they have lung cancer the first reaction usually is “did you smoke?” And it’s really kind of funny because when somebody comes down with diabetes nobody says, “Well how many Big Mac have you had?” When someone has a skiing accident nobody says ‘Well what were you doing on skis?” But for lung cancer, in particular we seem to have that “blame the person” sort of attitude. Heather Wakelee: And that’s very challenging for the patients who have never smoked but also for those who have. And those who do smoke or have smoked in the past are then given the tremendous guilt burden which they certainly don’t need as they’re trying to heal and live with their disease. And those who have never smoked are usually very, very distraught by those assumptions and questions. It’s devastating for everybody who gets lung cancer that stigmas there and that they’re asked about it and it comes up almost immediately. It’s not something that comes out later, it’s instead of the “What can I do to help?” that’s the question that comes out first “Did you smoke?” Reed Pence: Society has successfully demonized and stigmatized smoking in an effort to get people to quit or not start in the first place. But Schiller says it leaves lung cancer victims in an uncomfortable place. Joan Shiller: In the sixties and seventies when the anti-smoking campaign happened many of us remember those types of ads where smokers were depicted as decrepit, deformed, elderly people, and I think that unfortunately what that did was gave smokers and smoking a bad name, a bad image and now that’s backfiring. So, unfortunately instead of helping lung cancer patients, we blame them and somehow assume therefore they don’t need as aggressive treatments as patients with other types of cancer. Reed Pence: Schiller says she's often told by patients referred to her that doctors have offered no treatment and no hope. Joan Shiller: Unfortunately there is a great deal of nihilism around lung cancer which is becoming more and more unfounded. I mean, lung cancer is still incurable once its metastasized, but so are many other types of cancers once they’ve metastasized. And we have made small but sure steps in the treatment so people now are living longer and better with the treatments we have these days. Reed Pence: However, progress might have been quicker were it not for the stigma. Lung cancer kills more people than all other cancers, and more women than breast, ovarian, and uterine cancers combined. But Wakelee says lung cancer gets less money for research than many cancers. Heather Wakelee: A lot of folks are afraid to say that they’re behind lung cancer research because that’s looked at somehow as supporting smoking. We’re trying very hard to move away from that so people understand that this is a disease that kills innocent people that even people with smoking history certainly don’t deserve to have this disease, and we all should be working together to try to figure out better ways to treat. Joan Shiller: From the Federal Government, for example when you do it on a number of deaths per year, lung cancer gets one tenth of the amount of federal funding for research as does breast cancer for example. Reed Pence: However, researchers have still been able to uncover some important findings that are saving lives. We now know that lung cancer in nonsmokers is often different than it is in smokers. Joan Shiller: Never-smokers tend to get a type of lung cancer called Adenocarcinoma that is often associated with very specific mutations. And it turns out that if you have one of these mutations you will get lung cancer. I mean it drives lung cancer and we’ve identified more of what we call these “driver” mutations in never-smokers than we have in smokers. Heather Wakelee: Many lung cancers are caused by single mutations in different genes so these are mutations that are not found in the rest of the person but are only found in the tumor. And we understand that when a particular gene mutation happens that can be the driving force behind a given cancer. And what’s been identified is that it is more common to find these single gene mutations in people who develop lung cancer who have not smoked. People who develop lung cancer who have a smoking history are more frequently found to have multiple gene mutations, which are harder to target. Reed Pence: According to Schiller, about a quarter of lung cancers have one of these two mutations, which Wakelee says are known as ALK and EGFR. Heather Wakelee: And we find EGFR gene mutations in about 10% of all lung cancer. The percentage for people who have never smoked is higher somewhere in the 30,40, 50% range depending on the population versus in smokers it’s lower but it’s still found. If someone has a history of smoking but has an EGFR gene mutation their cancer is gonna behave the same as someone who doesn’t have a history of smoking and has an EGFR mutation. So it’s the molecular change in the cancer that’s just really trumping everything else. But the frequency of finding those mutations is higher for people who don’t have a smoking history. Reed Pence: Testing for whether a cancer has the EFGR or ALK mutation is important because doctors now have two drugs to treat them. The drugs are easy to take, and don't have the side effects of standard chemotherapy. They target only cells with those mutations. And most importantly, Mckee says, the drugs are extremely effective. Andrea McKee: These targeted therapies are a little bit like Babe Ruth, that if you look at his batting average he is just one of the greatest ball players out there and could really knock the ball out of the park. But if you looked at how many times he actually swung the bat, it’s not that many. And it’s the same concept with these treatments; they can be home runs and great treatments in the right patiet if they have the right target that we can manipulate with these different targeted treatments, but not everybody has them. And, so, when it works, it’s wonderful, and you can see really miraculous responses to the drugs. I mean, it’s amazing. People can have an extraordinary burden of disease and have a complete response with these targeted therapies--if they have the right gene profile for the drug that we’re using. Heather Wakelee: When we find those gene mutations, we can give oral medications, pills that work in the majority of patients so 60-70% of the time very rapid and dramatic responses to the therapy where the tumors shrink away. The challenge is still that those are not cures. The cancers do tend to re-grow, and that’s where ongoing research is looking at better drugs, newer drugs that’ll work when those stop. Reed Pence: The new-targeted therapies can buy some people with lung cancer years of quality time. A national clinical trial is seeking to find out whether these drugs might be curative if the cancer is found earlier. More standard therapies have a chance only when the cancer is caught early. But unlike for cancers such as prostate and breast cancer, guidelines haven't existed for lung cancer screening. Wakelee says that's finally changed. Heather Wakelee: We now do have recommendations for people with a heavy smoking history to get an annual screening CT scan. That’s something that’s offered at Stanford and at many other centers. The guidelines at this time focus only on patients who are at least 55 years old and have a significant smoking history. And as I mentioned, that’s still gonna miss a lot of the patients who are diagnosed with lung cancer either at an earlier age or without a smoking history. It’s a significant step forward because we have had trials completed that show that people who were getting these annual CT scans who were up in those high risk groups actually had a reduction in mortality meaning that fewer of them died from lung cancer if they were getting the CT Scans versus those who were not. So we have the capacity if we’re doing the low dose CT Scan screening in enough patients to lower the number of people dying of lung cancer. Andrea McKee: One of the areas where we’ve proven we’re going to save tens of thousands of lives each year over the next coming years is through screening and early detection. And, so, those are patients whom are at risk for lung cancer but have not yet been diagnosed with lung cancer. And, so, one of the messages we have to get out to primary care and to patients at risk is to learn about screening, learn about who would qualify as high risk and who would benefit from a low dose CT of the chest and enrolling in a CT lung screening program and teaching hospitals all over the country how to actually perform screenings safely. Because this is a new area of medicine that is really developing in real time. Most centers last year had no screening program. This year we’re seeing them develop all over the country because this is an area of medicine that is going to be adopted into standard clinical practice. Reed Pence: So little by little, medicine is making gains against lung cancer. It's still the world's number one cancer killer, but at least now, many of those diagnosed may have a fighting chance. You can find out about all of our guests on our website, radiohealthjournal.net, where you can also find archives of our segments. You can also find them on iTunes and Stitcher. I'm Reed Pence.