THESIS FIRST DRAFT (BODY)

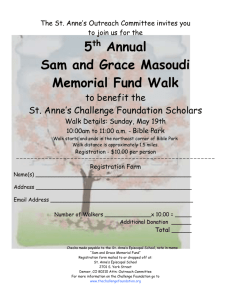

advertisement