Abstract - University of Arizona

Communicative Influence in Groups:

A Review and Critique of Theoretical Perspectives and Models

Renee A. Meyers

Department of Communication

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee meyers@uwm.edu

David R. Seibold

Department of Communication

University of California, Santa Barbara seibold@comm.ucsb.edu

Mirit D. Shoham

Department of Communication

University of California, Santa Barbara miriti@umail.ucsb.edu

Presented at the Second Annual Conference of the

Interdisciplinary Network for Group Research (INGRoup)

East Lansing, Michigan

July 12-14, 2007

1

2

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to survey and critique past and current theoretical perspectives on group influence. The number and scope of theories in this domain is vast, and as a way of delimiting the review, we define group influence as communicatively constituted in verbal exchanges.

We briefly overview four areas of theory and research that have contributed to our knowledge of group influence, and then focus more specifically on four theories within the Communication discipline that have addressed influence as communicatively constituted: Functional Theory (primarily Hirokawa and

Gouran’s version of it); Symbolic Convergence Theory (which focuses on how relational aspects of influence can impact groups’ instrumental goals); Hewes’ Socio-Egocentric

Model (which establishes a baseline test of communicative influence in groups); and

Structuration Theory (especially Seibold, Meyers and colleagues’ group argument research). We assess each of these theoretical perspectives in terms of the research support that exists for each theory and, in the conclusion, identify criticisms of the theories and an agenda for future work.

3

Communicative Influence in Groups:

A Review and Critique of Theoretical Perspectives and Models

We view communicative influence in groups as focused on instrumental goals and related individual, subgroup, and system effects that are constituted in verbal exchanges among group members who interact face-to-face or can readily do so.

We do not exclude studies (attendant to each to the four theories we review) that investigate computermediated and distributed groups, but neither are they our primary context. Because theory and research on communicative influence in groups is extensive, we use this definition as a framework for selection of the theories we treat. Our focus on influence as communicatively constituted offers a standpoint from which to assess the group communication perspectives we examine and interdisciplinary perspectives we acknowledge.

We first survey four areas that have provided the foundations for, and understanding of, communicative influence in groups: classic works on social influence; interdisciplinary perspectives on group influence insufficiently integrated by

Communication researchers; Communication perspectives on groups in which influence has not been a central concern; and influence perspectives from other disciplines which have been appropriated by Communication researchers. Across these areas, some of the works have not studied groups per se and many have not investigated communicative influence, but all provide a context on social influence that is foundational to the four theories we do examine. In the main portion of the paper we focus specifically on theoretical perspectives that view group influence in terms of communicative processes and effects. We explicate Functional Theory (primarily Hirokawa and Gouran’s version of it);

4

Symbolic Convergence Theory (which focuses on how relational aspects of influence can impact groups’ instrumental goals); Hewes’ Socio-Egocentric Model (which establishes a baseline test of communication-as-influence in groups); and Structuration Theory

(especially Seibold, Meyers and colleagues’ group argument research). We assess each of these theoretical perspectives in terms of the research support for each theory and, in the conclusion, identify theoretical controversies that surround the theory.

Group Influence Foundations

Although we must bypass a great deal of theory and research on social influence, a cursory history of theorists who laid the foundation for influence research–often but not always in groups—is instructive. Prominent theorists include Asch (1951) on conformity processes, Festinger’s (1956) theory of social comparison processes, Zajonc’s (1965) social facilitation perspective, French and Raven’s (1968) distinctions among the bases of social power, and others whose work has informed our understanding of influence in groups and organizations. These early works were integral in shaping the interdisciplinary nature of this research area.

There also is a set of theoretical perspectives and models from other disciplines, principally Social Psychology, that have much to say about interpersonal influence in groups yet which have not been sufficiently integrated into studies of communicative influence in groups by Communication scholars. Among the most prominent are perspectives on minority influence—especially those stemming from Turner (1974) and

Tajfel (1974, 1979) and Social Identity Theory (Martin & Hewstone, 2007); Stasser’s

(Stasser, Vaughn & Stewart, 2000) information distribution and distillation perspective;

Latané’s Social Impact Theory (1981)—and Jackson’s extension of it in the Social Forces

5

Model of Influence (1987); Wegner’s Transactive Memory Perspective: (e.g., Wegner,

Erber, & Raymond, 1991); Hopkin’s position on the exercise of influence; McGrath’s Time

Interaction Performance (TIP) Model (1991); and Bales’ SYMLOG and its reliance on

Field Theory (Bales & Cohen, 1979 (for a notable exception in communication, albeit not focused on influence, see Keyton & Wall, 1989).

Third, there are theoretical frameworks in Communication that acknowldege influence in groups but whose proponents have not been centrally focused on communicative influence. Some of the more prominent of these include development models (Poole &

Baldwin, 1996); Fisher and Hawes’ Interact System Model (1971); Putnam and Stohl’s

Bona Fide Groups Perspective (1996); and Salazar’s Mediational Perspective on group decision making (Hirokawa & Salazar, 1997; Salazar et al., 1994).

Finally, there is a set of social influence perspectives from outside the field that

Communication scholars have drawn upon, and that have shaped work on group influence in the Communication discipline. These include Price, Cappella and Nir’s (2002) use of the Deutsch and Gerard (1955) perspective for their work on normative and information influences in online political discussions; Propp’s (1997) use of Stasser’s work in her formulation of the evaluative interaction model; Boster’s (Boster, Fryrear, Mongeau, &

Hunter, 1982) reliance on French’s (1956) linear discrepancy model; Hollingshead’s

(Hollingshead, McGrath, & O’Connor, 1993) tests of the TIP Model as well as

Hollingshead’s (Hollingshead & Brandon, 2002) and Wittenbaum’s (2002) work drawing upon group memory; and minority influence work starting with Alderton and Frey (1983).

Group Communication Theories and Influence

6

In this section, we focus more specifically on theoretical perspectives that conceptualize influence most closely with how we have defined it for this paper. We overview four prominent perspectives—Functional Theory, Symbolic Convergence

Theory, the Socio-Egocentric Model, and Structuration Theory. As a framework for describing how influence is conceived in each perspective and illuminating similarities and differences between the conceptions, we structure our review around two tensions that characterize influence interactions. These tensions relate to our definition of group influence as instrumental goals and related effects, and are central concepts in recent theories of social action (e.g., Bourdieu, 1977; DeCerteau, 1984; Giddens, 1979, 1984;

Sahlins, 1987). The first tension asks whether the source of influence attempts is constituted in individual/group agency or determined by institutional structures, or both?

The second tension queries whether the individual, subgroup, and/or system effects that accrue from these influence attempts are intentional or unintentional, or both?

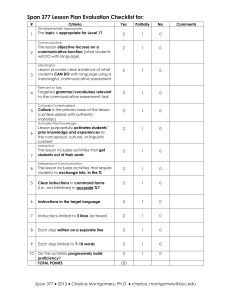

These two tensions provide the scaffolding for our analysis of social influence within each of the four perspectives (see Table 1). This framework for describing and evaluating these four conceptualizations of social influence in groups offers only one lens for analysis. Alternative frameworks and/or criteria could be employed that would provide a different, and potentially contrasting, viewpoint We believe this structure provides insight into the varied ways that group influence has been, and can be, conceptualized. We also hope our analysis demonstrates how these four views of influence have generated significant research findings regarding the role, function, and impact of group influence.

Functional Theory and Influence

7

One of the most prominent theories of communication and group decision making is the functional theory of group decision making (Gouran & Hirokawa, 1983, 1986, 1996;

Gouran, Hirokawa, Julian, & Leatham, 1993; Hirokawa, 1980a, 1980b, 1982, 1983, 1985,

1988, 1999; Hirokawa, Erbert, & Hurst, 1996; Hirokawa & Rost, 1992; Hirokawa &

Scheerhorn, 1986). This theoretical perspective advances five communicative functions as prerequisites to effective decision making (Hirokawa, 1999; Hollingshead et al., 2005): (a) garnering a complete and thorough understanding of the problem, (b) recognizing the specific standards or criteria needed for an acceptable solution, (c) generating a range of feasible solutions, (d) assessing thoroughly and accurately the positive consequences of each solution, and (e) assessing thoroughly and accurately the negative consequences of each solution How group members communicatively produce (or fail to produce) each of these five functions significantly affects the final group outcome.

To date, empirical and laboratory research has provided general support for the functional perspective and its model of communicative influence (e.g., Cragan & Wright,

1993; Hirokawa, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1985, 1987, 1988: Hirokawa, Ice, & Cook, 1988,

Hirokawa & Johnston, 1989, Propp & Nelson, 1996). Additionally case study investigations of failed decisions have pointed out some of the deficiencies that impair effective production of the five functions, resulting in no influence, or ineffective influence, on final outcomes (e.g., Gouran, 1984, 1987, 1990; Gouran, Hirokawa, & Martz, 1986,

Hirokawa, Gouran, & Martz, 1988). Moreover, some research in this tradition suggests that there may be contingency variables that mediate the influence of the five functions

(such as the nature of the task, Hirokawa, 1990). More recently, a meta-analysis of empirical research analyzing the functional theory indicated that assessment of negative

8 consequences was the most influential communicative function for producing effective decisions (Orlitzky & Hirokawa, 2001).

In light of our framework, we classify functional theory’s view of group influence as one where (a) individuals/groups have agency to influence instrumental goals through communication related to the five functions, and (b) influence effects in group decision making are generally intentional in nature (hence its placement in the upper left quadrant of

Table 1). Functional theorists believe that individual group members (and ultimately, the group as a whole) have the ability to influence decision making outcomes through effective use of the five requisite functions. As Gouran and Hirokawa (1996) state,

“[C]ommunication is the instrument by which members of groups, with varying degrees of success, reach decisions and generate solutions to problems” (p. 55).

On this view, group members are capable of influencing each other and the final group outcome. Although group members may draw on institutional structures (status, gender, expertise, language) to produce influence, functional theorists have not been particularly interested in identifying those resources or how they might be employed. Of greater interest are the micro-interaction behaviors that group members produce as they seek to influence decision proposals (Hirokawa, 1980, 1983a, 1983b, 1985, 1987, 1988;

Hirokawa & Pace, 1983, Hirokawa & Rost, 1992). Reflective of this view is Gouran and

Hirokawa’s (1996) analysis of how group members might counteract cognitive, affliative, and egocentric constraints in decision-making interactions. Group members are assumed to be capable of counteracting these constraints through communicative influence strategies such as questioning members’ evidence, heightening awareness of relationships, engaging

9 powerful members in reflection and examination, and clarifying the facilitative role of argument, among other discourse options.

Moreover, within functional theory, influence effects are primarily conceived as intentional. Researchers in this program view group members as aware and motivated to bring about a desired outcome. For example, Gouran and Hirokawa (1996) suggest that group members can, “take steps to minimize and counteract sources of influence that limit prospects for adequately fulfilling fundamental task requirements” (p. 75). Additionally, as

Hirokawa and Salazar (1999) explain, “interaction is a social tool that group members use to perform or satisfy various prerequisites for effective decision making” (p. 169).

In short, the functional perspective views social influence as produced by group members who are capable of intentionally impacting group outcomes through use of various communicative strategies. In general, less attention is paid to the ways that macrostructures might determine influence or the unintentional effects of various tactics. The result is a view of social influence that accords strong agency to individual group members to bring about intended influence for the production of high quality decisions.

Symbolic Convergence Theory and Influence

Symbolic Convergence Theory (SCT) posits a view of social influence unique from that of functional theory. In terms of our framework, SCT falls in the upper right quadrant

(see Table 1) where group members have agency, but the effects tend to be unintentional.

SCT grows out of early research on learning groups by Bormann and colleagues (Bormann,

1969; 1972; 1982, 1986; 1996; Bormann, Bormann, & Harty, 1993; Bormann, Cragan, &

Shields, 1994; Bormann, Pratt, & Putnam, 1978). This program of research investigates how groups create a shared consciousness that binds group members together as a cohesive

10 unit. Group members develop symbolic convergence through the sharing of group fantasies.

Bormann (1996) defines fantasies as “the creative and imaginative shared interpretation of events that fulfill a group psychological or rhetorical need” (p. 88). They include any message that does not refer to the immediate “here and now” of a group, which might include jokes, anecdotes, fables, analogies, or imagined futures. As group members converge around a symbolic representation of their group, they may use the shared fantasy to influence, guide, and motivate their actions, and as a means for unification. Symbolic convergence can create a sense of common identity, foster creativity, influence assumptions and premises, and suggest both realistic and unrealistic ways of coping with problems (Bormann, 1996; Poole, 1999).

Symbolic Convergence Theory posits group members as active agents in creating and maintaining fantasies, which then have an instrumental influence on decision-making outcomes. Bormann (1996) suggests that the influential impact of fantasies often rests with the rhetorical skills of the group participants, and that members of consciousness raising groups especially, use dramatizing messages for attracting attention or relieving social tension in the group (Bormann, 1982c). Hence, as members share their interpretations, and as other members elaborate these dramatizations, the group comes to experience similar emotions and develop similar experiences. In time, some of these shared interpretations become fantasy types that influence the group’s outlook, identity, and actions.

Past research in this program has focused on identifying how SCT is influential in a variety of communicative situations—focus groups, political cartoons, corporate strategic planning, fire safety education, covens—among other contexts (Bormann, 1973, 1982a,

11

1982b, 1983, 1985, 1996; Bormann, Bormann, & Harty, 1995, Bormann, Koester, &

Bennett, 1978; Cragan & Shields, 1977, 1992; Lesch, 1994; Putnam, Van Hoeven, &

Bullis, 1991). In addition, researchers within SCT have revised and extended this theory in response to criticism in the field, and have worked to re-vision the theory to encompass the impact of SCT in both rhetorical and group contexts (e.g., Bormann, 1982a, Bormann,

Cragan, & Shields, 1994, 1996).

Unlike functional theory SCT does not necessarily view the effects of these influence attempts as intentional. In fact, Bormann (1996) suggests that group members respond positively to some fantasies, in a “ho-hum” fashion to others, and reject still other fantasies. Hence it is unclear which fantasies will be utilized to influence, and how that influence will be constituted in the group. The way in which two or more symbolic worlds come to overlap (or not) is more accidental than not, and outcomes of fantasies often have unintended consequences. Moreover, Bormann (1996) indicates that groups may

“accidentally create a consciousness that is more or less conducive to good problem solving without being aware of what they are doing” (p. 99). In short, SCT provides an account of influence in which actors are actively involved in sharing fantasies through communicative discourse. The persuasive effect of these fantasies, however, is more typically accidental and unplanned. The result is that they can be facilitative or inhibitive in shaping and guiding the group’s decision making process (Bormann, Pratt, & Putnam, 1978).

Socio-Egocentric Model and Influence

In proposing the socio-egocentric model, Hewes (1986; 1996) argues that there is little hard-and-fast evidence to back claims that communicative influence has any impact at all on decision outcomes. He states, “My approach is based on the assumption that much,

12 if not all, small group communication is epiphenomenal—that is, identifiable noninteractive factors can explain observed patterns of group communication, and it is these noninteractive inputs that produce decision outputs” (p. 193). Hence, Hewes’ socioegocentric model explains influence without recourse to group interactions.

Hewes’ socio-egocentric model assumes that group members’ communication is generated by, and reflective of, input factors and members’ previous behavior. Groups are sets of people who act individualistically. Members’ interaction is governed by larger macro-structures—such as turn-taking rules and norms about vacuous comments—that make it appear as though the group is working collectively. But there is no actual influence occurring in the group. Members are merely engaged in a process that unfolds identically for each person so as to produce the appearance of coherence and influence.

We are placing the socio-egocentric model in the lower right quandrant of our table

(see Table 1) although its placement is debatable. The sources of influence in this model are noninteractive input factors—broader institutional structures that determine interaction patterns. Group members employ “a structural norm of conversation (turn taking) and a cosmetic bid toward meaningful extension of the conversation (vacuous acknowledgments)” (Hewes, 1996, p. 195) to produce collective discourse. Hence members have little agency in this model; norms of language and communicative practice structure the flow of interaction.

In a similar vein, we posit that influence effects in the socio-egocentric model are largely unintentional in nature. That is, the interaction patterns accrue as a result of individuals’ internalization of macro-level rules and norms that allow them to produce a form of patterned discourse (Bourdieu, 1984). In other words, the fact that groups produce

13 consistent and coherent decision-making discourse has nothing to do with the intentions or agency of the group members themselves.

As a postscript to our analysis of the socio-egocentric model, we note that the model of influence that Hewes (1996) suggests as an alternative to the SE model conceives of influence as a linear, strictly sequential process that is best captured by “temporally systematic lags between the occurrence of an action and the action that triggered it” (p.

206). This model assumes influence is best understood as individual-to-individual, act-toact dependencies. We would place this alternative model of influence in the upper left quadrant of Table 1 since it posits both individual agency and assumes intentional effects.

Structuration Theory and Influence

Structuration Theory (Giddens, 1984; Poole, Seibold, & McPhee, 1985, 1996) addresses the production and reproduction of groups and the factors that are implicated in that process. Much of the work on influence within this theoretical realm in communication has focused on group argument (Brashers et al., 1994; Brashers, Adkins,

Meyers, & Mittleman, 1995; Brashers & Meyers, 1989; Canary, Tanita-Ratledge, &

Seibold, 1982; Canary, et al., 1987; Considine, Meyers, & Timmerman, 2006; Gebhardt &

Meyers, 1995; Lemus et al., 2004; Meyers, 1989a, 1989b; Meyers & Brashers, 1998;

Meyers et al., 1991; 2000; Meyers, Brashers, Winston, & Grob, 1997; Meyers & Seibold,

1989; Meyers & Seibold, 1990; Meyers et al, 1991; Ratledge, 1986; Seibold et al., 1981,

1983; Seibold & Lemus, 2005). Within this Structurated Group Argument (SGA) perspective, arguments are both systems (observed patterns of interaction) and structures

(the unobservable generative rules and resources that enable argument) that produce and reproduce each other. “Argument systems are produced in interaction through interactants’

14 knowledgeable and skillful (but perhaps unreflective and unarticulated) use of particular rules and resources—a process that in turn reproduces those structures and makes them available as future resources (Seibold & Meyers, 1986, p. 148). In short, arguments are both the medium and outcome of group interaction (Meyers & Seibold, 1990).

The SGA research program has investigated argument patterns and structures

(Seibold et al. 1981; Canary et al., 1982, 1987; Meyers & Seibold, 1990; Meyers et al.,

1991); compared cognitive (Persuasive Arguments Theory) and interactional accounts of argument (Meyers, 1989a, 1989b; Meyers & Seibold, 1989); revealed group members’ joint production of argument (Seibold et al. 1981) and strategies of tag-team argument

(Brashers & Meyers, 1989); explored the role of sex differences (Meyers et al., 1997), majority and minority subgroup differences (Gebhardt & Meyers, 1995; Meyers et al.,

2000), and individual differences in message design logic (Morris, Seibold, & Meyers,

1991) in group argument; investigated argument in computer mediated groups (Brashers et al., 1994; Brashers et al., 1995; Lemus et al., 2004; Lemus & Seibold, 2004), and posited a model of group argument to test a set of argument process-outcome relationships (Meyers

& Brashers, 1998).

Theoretically, the structurational view of group argument accounts for both individual/group agency and institutional structural factors in the production of instrumental goals. In addition, it also allows for both intentional and unintentional effects or consequences (Giddens, 1984). So, theoretically, the SGA conception of social influence encompasses all four quadrants in Table 1.

Practically, however, most of the work on group argument-as-influence has focused on the left half of the diagram pictured in Table 1. Much of the descriptive work on group

15 argument in both face-to-face and computer-mediated groups has explored how individuals and/or groups produce argumentative interaction. The work on argument effects has primarily assumed intentional consequences—that is, group members are viewed as producing certain arguments in order to intentionally influence a decision proposal (see

Meyers & Brashers, 1998; Meyers et al., 2000; Lemus et al., 2004).

Less characteristic in this program of work is research on the structural or institutional factors that are implicated in the argumentative process. Some early work involving an evaluation of Persuasive Arguments Theory (a cognitive-information based argument perspective) investigated if and how group members implicate cognitive arguments in actual discussion interaction (Meyers, 1989a, 1989b). Moreover, work by

Canary et al. (1987) illustrated how various rules and resources serve to generate predictable argument structures. Additionally, work by Poole and colleagues on Adaptive

Structuration Theory (e.g., DeSanctis & Poole, 1994; Jackson & Poole, 2003; Poole &

DeSanctis, 1990, 1992) has demonstrated how group members appropriate various GDSS rules and resources in virtual decision-making interaction (See Table 1 and the placement of AST). However, to date, work on social influence within the structurational program has primarily viewed influence as prompted by capable actors producing intentional outcomes.

In sum, we have framed our discussion of social influence at the group level around two tensions—individual agency versus institutional determination, and intentional versus unintentional effects. This framing has allowed us to more clearly illustrate some of the similarities and differences in these four conceptions of social influence and to highlight major findings associated with each perspective. Still, we view the placement of these

16 theories as eminently debatable, and we trust readers will take up that challenge.

Moreover, by limiting our discussion to just these two tensions, we have been forced to bypass many other factors that define these views of social influence. We recognize that all four perspectives offer a view of communicative influence in groups that is more complex and far richer than can be illustrated in this analysis.

Conclusion

In the preceding sections we sought to accomplish four aims. First, we delineated group influence that is communicatively constituted and defined our conception of it.

Second, we noted four research traditions on social influence and group influence—from across disciplines that study group behavior--that have been foundational to, or parallel with, prominent theories of group communication. Third, we introduced a conceptual framework for comparing and contrasting those four perspectives in terms of source of influence (agency or structure) and type of effect (intentional or unintentional). Fourth, we examined each theory’s stance on influence and reviewed relevant evidence. In the remainder of the paper we take up a fifth objective: to critique these four group communication theories, surveying others’ assessments and interspersing them with our own. Although we believe the most urgent agenda is to redress the problems we identify, we also offer suggestions for future theoretical and empirical work.

Critique of Theoretical Perspectives

Functional Theory . Stohl and Holmes (1993) note the extensive reliance on zerohistory laboratory groups in tests of Functional Theory. Despite an important field study by Propp and Nelson (1996) of group problem solving functions by teams in a manufacturing organization, little has been done to extend test of the theory to groups in

17 situ and to assess generalizability. Furthermore, as Waldeck, Shepard, Teitelbaum, Farrar, and Seibold (2002) summarize, conceptual ambiguities and operational disparities surrounding group “functions” and “effectiveness” undermine the ability to track communicative influence in task groups and assess influence effects, and thus to draw comparisons about influence across studies. Especially problematic from the standpoint of understanding communication influence in the context of members’ enactments of decision making functions, proponents of the theory generally assume that members have all relevant information needed to enact the functions specified in the theory. Little attention is accorded to varying representations of that information (or to representational gaps,

Cronin & Weingart, 2007), to its distribution to and among members, and to the criteria used to assess that information vis-à-vis the functions specified by the theory. All are likely to involve communicative influence, and therefore should be part of an agenda for future research. Similarly, Gouran and Hirokawa (1996) and Gouran (1998) have acknowledged the salience of cognitive, affiliative, and egocentric constraints on members’ ability to make appropriate choices and Gouran (1998) has posited interactional manifestations of these constraints on group decision making, but an important agenda item for future research will be to empirically assess them.

Symbolic Convergence Theory . SCT studies have yielded intriguing descriptions of the emergence of fantasy chaining and the unfolding of rhetorical visions. However, SCT investigations have been largely uninformative in terms of theoretical accounts and predictions for how these processes influence group outcomes. This is not surprising given the resistance by SCT proponents (e.g., Bormann et al, 1994) to calls for specification of process-product linkages. Waldeck et al (2002) proposed nearly a dozen predictions,

18 nested within three overarching propositions, but more theorizing and much empirical work is needed to formalize and test the theory. Too, although SCT investigations afford rich accounts of communicative influence in groups in a broad sense (i.e., messages that contribute to fantasy chains, rhetorical vision, and ultimately symbolic convergence), they are incomplete in terms of the structure of member-to-member(s) communicative influence.

This limitation is, in part, a consequence of the absence of a priori theory concerning the causes and consequences of fantasy chaining. Just as we need to know more about the specific communicative and interactional functions necessary for symbolic convergence to occur, as well as functions that specific master analogues fulfill within groups (Waldeck et al., 2002), we also need to know much more about the form and functions of members’ verbal exchange and their interdependent nature as communicative influence in those processes.

Socio-Egocentric Model . Beyond a view of group communication as information sharing and a mere conduit for preference displays, the theoretical importance and predictive utility of communicative influence processes in groups—relative to input-output models—can be found in theoretical discussions and literature reviews by Gouran (1999),

Jarboe (1999), Meyers & Brashers (1999), and Pavitt (1993) among others. Tschan (1995) has provided evidence of conditions under which communication enhances group productivity in general. More germane for underscoring the potential importance of communication in group decision making, Hoffman and Kleinman (1994) found that the valence of group members’ statements concerning decision choices not only exerted an influence on decision outcomes in particular, but that those outcomes could not be

19 adequately predicted by the distribution of those members choice preferences before they interacted.

However, as we have seen, Hewes (1986, 1996) offers an alternative view: (a) if communication influence is said to exist in groups, it must be found in member-to-member, act-to-act sequential structures (i.e., influence occurs when a group member’s communication behaviors are demonstrated to be contingent upon another’s immediately preceding message acts), and (b) since no unambiguous evidence exists for same to date, it must be found if there is to be any value for communication-based explanations of group processes and outcomes (also see Pavitt, 1999 on the second point). Poole (1999) astutely offers three criticisms of Hewes’ first proposition, the pivotal one in Hewes’s account.

First, Hewes’ conceptualization of group communication as individual-to-individual influence is overly restrictive and precludes communicative influence as member convergence surrounding a common viewpoint. We note this is consistent with Symbolic

Convergence Theory and the empirical evidence SCT proponents offer.

Second, Hewes’ insistence on act-to-act influence tied to conditional probabilities precludes the influence(s) of critical communication events whose effects are found in much later parts of the group’s interactional history, and in lagged, non-dyadic, or broken interactional chains. We remind that this is what is proposed by Structuration Theory and is reported in studies of tag-team subgroup argument influence (Brashers & Meyers, 1989;

Seibold et al., 1981). Working from a non-ST perspective, Corman and Kuhn (2005) applied a quasi-Turing test to determine if group members could distinguish simulated socio-egocentric speech from speech generated by real human groups. Their results suggest that “people may employ different criteria as evidence of influence in group

20 interaction than the linked content of utterances proposed by Hewes” (p. 140). In short, influence in group discussion may well be more complex and varied than individual-toindividual, act-to-act dependencies.

Third, Hewes’ emphasis on communicative influence as changes in subsequent behaviors in the direction advocated ignores other influences that may occur in response to individual acts (e.g., reactance effects). Indeed, support for the Valence Model (Hoffman &

Kleinman, 1994) and Distributed Valence Model (McPhee, Poole, & Seibold, 1982;

Meyers, Brashers, & Hanner, 2000; Poole, McPhee, & Seibold, 1982) may involve precisely such influences. Notwithstanding these critiques and evidence consistent with them, empirical findings consistent with Hewes’s restrictive conception of communicative influence in groups should also be sought.

Structuration Theory . Critiques of ST have centered on two facets of group structuration studies. First, as Gouran (1990) detailed, the over-emphasis on studies of group structuring processes, rather than process-outcome linkages, meant that the predictive potential of ST had not been exploited. This concern has been explicitly addressed in some recent studies (Lemus & Seibold, 2004; Lemus et al., 2004; Meyers &

Brashers, 1998; Meyers, Brashers, & Hanner, 2000), but much more work is needed.

Second, empirical demonstrations of the theoretical tenet of action-structure recursivity have been scant (Contractor & Seibold, 1993). As a result we have little insight into their dual influences in groups, and their unintended effects.

Future Research Agenda

In the introductory section we noted the many theoretical perspectives on social influence from other disciplines, especially social cognition models in Social Psychology,

21 with potential links to the study of communicative influence, have not been fully considered. As reviewed by Martin and Hewstone (2007), there are numerous approaches to majority (numerical size, normative position, or power relationship) influence on opinion minority members’ agreement and conformity, and to minority influence on majority change: conversion theory (Moscovici, 1980; 1985), convergent-divergent theory (Nemeth,

1986; 1995), social-impact theory (Latané, 1981; 1996) and the social-impact model

(Tanford & Penrod, 1984), the objective-consensus approach (Mackie, 1987), conflictelaboration theory (Perez & Mugny, 1996), the context/comparison model (Crano &

Alvaro, 1998), and self-categorization theory (David & Turner, 1996). Many of these perspectives assume, theorize, or empirically test the effects of persuasive messages on group members’ cognitions.

For example, Moscovici asserts that in their efforts to reduce the inevitable internal conflict associated with majority influence, minority members “compare” themselves to the majority –concentrating on “what others say , so as to fit in with their opinions or judgements” (Moscovici, 1980: 214 italics added). In contrast to this conversion theory,

Mackie’s (1987) objective-consensus approach posits that members attend to and process majority messages more that minority messages. The observational and content analysis methods typically utilized in Communication scholars’ studies of group influence also could be employed to track the communication process correlates and effects of these powerful theoretical explanations and predictions about member influence (see Meyers,

1989a and 1989b for a similar communication test of persuasive arguments theory).

Even as we probe communicative influence at the level of individual members and subgroups, more must be done to understand discursive processes that lead to joint,

22 collective outcomes. Teams’ achievement of high levels of collaborative decision making makes theoretically problematic how members communicatively attain such higher levels of coordination. Weick’s (1995; Weick & Roberts, 1993) sensemaking and Cooren’s

(2004) collective minding perspectives for explaining the emergence of collective mind, simultaneously try to account for larger organizational and social structures – in which groups are embedded -- that limit and facilitate the communication processes that inhere in heedfulness. McPhee, Myers, and Trethewey (2006) provide a compelling analysis of the requirements for establishing the communicative bases of collective mind as well as the organizational structures that constrain those processes, and they offer examples from the research literature that are suggestive of the types of studies that could be done by communication influence researchers interested in higher level consciousness and coordination as discursive achievement.

23

Table I

Source of Influence Goals Types of Influence Effects

Intentional Unintentional

Individual/Group Agency Functional Theory

Structurated Group Argument

Symbolic Convergence Theory

Institutional Structural Factors Adaptive Structuration Theory Socio-Egocentric Model

24

References

Alderton, S. M., & Frey, L. R. (1983). Effects of reactions to arguments on group outcome:

The case of group polarization. Central States Speech Journal , 34 , 88-95.

Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In H. S. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups, leadership, and men: Research in human relations (pp. 177-190). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Press.

Bales, R. F., & Cohen, S. E. (with Williamson, S. A.) (1979). SYMLOG: A system for the multiple level observation of groups . New York: Free Press.

Bormann, E. G. (1969). Discussion and group methods: Theory and practice . New York:

Harper & Row.

Bormann, E. G. (1972). Fantasy and rhetorical vision: The rhetorical criticism of social reality. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 58, 396-407.

Bormann, E. G. (1973). The Eagleton affair: A fantasy theme analysis. Quarterly

Journal of Speech, 59 , 143-159.

Bormann, E. G. (1982a). Fantasy and rhetorical vision: Ten years later. Quarterly

Journal of Speech, 68 , 288-305.

Bormann, E. G. (1982b). A fantasy theme analysis of the television covrage of the hostage release and the Reagan inaugural. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 68 , 133-145.

Bormann, E. G. (1982c). The symbolic convergence theory of communication and the creation, raising, and sustaining of public consciousness. In J. Sisco (Ed.), The

Jensen lectures: Contemporary communication studies (pp. 71-90). Tampa, FL:

University of South Florida, Department of Communication.

25

Bormann, E. G. (1983). Symbolic convergence: Organizational communication and culture. In L. Putnam & M. E. Pacanowsky (Eds.), Communication and organizations: An interpretive approach (pp. 99-122). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Bormann, E. G. (1985). Symbolic convergence theory: A communication formulation based on homo narrans . Journal of Communciation, 35(4), 128-139.

Bormann, E. G. (1996). Symbolic convergence theory and communication in group decision making. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and group decision making (2 nd

ed., pp. 81-113). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bormann, E. G., Bormann, E., & Harty, K. C. (1995). Using symbolic convergence theory and focus group interviews to develop communication designed to stop teenage use of tobacco. In L. R. Frey (Ed.), Innovations in group facilitation: Applications in natural settings (pp. 200-232). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Bormann, E. G., Cragan, J. F., & Shields, D. C. (1994). In defense of symbolic convergence theory: A look at the theory and its criticism after two decades.

Communication Monographs, 44, 259-294.

Bormann, E. G., Koester, J., & Bennett, J. (1978). Political cartoons and salient rhetorical fantasies: An empirical analysis of the ’76 presidential campaign. Communication

Monographs, 45 , 317-329.

Bormann, E. G., Pratt, J., & Putnam, L. (1978). Power, authority, and sex: Male response to female leadership. Communication Monographs, 45 , 317-329.

Boster, F. J., Fryrear, J. E., Mongeau, P. A., & Hunter, J. E. (1982). An unequal speaking linear discrepancy model: Implications for the polarity shift. In M. Burgoon (Ed.),

Communication yearbook 6 (pp. 395-418). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

26

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice . Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Brashers, D. E., Adkins, M., & Meyers, R. A. (1994). Argumentation in computermediated decision making. In L. Frey (Ed.), Communication in context: Studies of naturalistic groups (pp. 262-283). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Brashers, D. E., Adkins, M., Meyers, R. A., & Mittleman, D. (1995). The facilitation of argumentation in computer-mediated group decision making interactions. In F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A. Blair, & C. A. Willard (Eds.), Special fields and cases: Proceedings of the third ISSA conference on argumentation (pp. 606-621).

Amsterdam: Foris Publications.

Brashers, D., & Meyers, R. A. (1989). Tag-team argument and group decision-making: A preliminary investigation. In B. Gronbeck (Ed.), Spheres of argument: Proceedings of the sixth SCA/AFA conference on argumentation (pp. 542-550). Annandale, VA:

Speech Communication Association.

Canary, D. J., Brossmann, J., Brossmann, B. G., & Weger, H. Jr. (1995). Toward a theory of minimally rational argument: Analyses of episode-specific effects of argument structures. Communication Monographs, 62 , 183-212.

Canary, D. J., Brossmann, B. G., & Seibold, D. R. (1987). Argument structures in decision-making groups. Southern Speech Communication Journal, 53, 18-37.

Canary, D. J., Ratledge, N. T., & Seibold, D. R. (1982, November). Argument and group decision-making: Development of a coding scheme.

Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Speech Communication Association, Louisville, KY.

27

Considine, J., Meyers, R. A., & Timmerman, C. E. (2006). Evidence use in group quiz discussions: How do students support preferred choices? Journal for Excellence in

College Teaching. 17, 65-89.

Contractor, N. S., & Seibold, D. R. (1993). Theoretical frameworks for the study of structuring processes in group decision support systems: Comparison of adaptive structuration theory and self-organizing systems theory. Human Communication

Research, 19, 528-563.

Cooren, F. (2004). The communicative achievement of collective minding: Analysis of board meeting excerpts. Management Communication Quarterly , 17 (4), 517-551.

Corman, S. R., & Kuhn, T. (2005). The detectability of socio-egocentric group speech: A

Quasi-Turing test. Communication Monographs, 72 , 117-143.

Cragan, J. F., & Shields, D. C. (1977). Foreign policy communication dramas: How mediated rhetoric played in Peoria in Campaign ’76.

Quarterly Journal of Speech,

63, 274-289.

Cragan, J. F., & Shields, D. C. (1992). The use of symbolic convergence theory in corporate strategic planning: A case study. Journal of Applied Communication

Research, 20 , 199-218.

Cragan, J. F., & Wright, D. W. (1990). Small group communication research of the 1980s:

A synthesis and critique. Communication Studies, 41 , 212-236.

Crano, W. D., & Alvaro, E. M. (1998). The context/comparison model of social influence:

Mechanism, structure, and linkages that underlie indirect attitude change. In W.

Stroebe & M. Hewstone (Eds.), European review of social psychology, Vol. 8 (pp.

175-202). Chichester: Wiley.

28

Cronin, M. A., & Weingart, L. R. (2007). Representational gaps, information processing, and conflict in functionally diverse groups. Academy of Management Review, 32 ,

761-773.

David, B., & Turner, J. C. (1999). Studies in self-categorization and minority conversion:

The ingroup minority in intragroup and intergroup contexts. British Journal of Social

Psychology, 38, 115-134. de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life . Berkeley, CA: University of

California Press.

DeSanctis, G., & Poole, M. S. (1994). Capturing the complexity in advanced technology use: Adaptive structuration theory. Organization Science, 5 , 121-147.

Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. G. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influence upon individual judgment. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51 ,

629-636.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117-

140.

Fisher, B. A., & Hawes, L. C. (1971). An interact system model: Generating a grounded theory of small groups. Quarterly Journal of Speech , 57 , 444-453.

French, J. R. P. Jr. (1956). A formal theory of social power. Psychological Review, 63 ,

181-194.

French, J. R. P. Jr., & Raven, B. (1968). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright & A.

Zander (Eds.), Group dynamics (pp. 259-269). New York: Harper & Row.

29

Gebhardt, L. J., & Meyers, R. A. (1995). Subgroup influence in decision-making groups:

Examining consistency from a communication perspective. Small Group Research,

26, 147-168.

Giddens, A (1979). Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration .

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gouran, D. S. (1984). Communication influences related to the Watergate coverup: The failure of collective judgment. Central States Speech Journal, 35 , 260-268.

Gouran, D. S. (1987). The failure of argument in decisions leading to the “Challenger disaster”: A two-level analysis. In J. W. Wenzel (Ed.),

Argument and critical practices: Proceedings of the Fifth SCA/AFA Conference on Argumentation (pp.

439-448). Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association.

Gouran, D. S. (1990a). Factors affecting the decision-making process in the Attorney

General’s Commission on Pornography: A case study of unwarranted collective judgment. In R. S. Rodgers (Ed.), Free speech yearbook 28 (pp. 104-119).

Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Gouran, D. S. (1990b). Exploiting the predictive potential of structuration theory. In J. A.

Anderson (Ed.), Communication yearbook 13 (pp. 313-322). Newbury Park, CA:

Sage Publications.

Gouran, D. S. (1999). Communication in groups: The emergence and evolution of a field of study. In L. R. Frey, D. S. Gouran, & M. S. Poole (Eds.), The handbook of group communication theory and research (pp. 3-36). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

30

Gouran, D. S., & Hirokawa, R. Y. (1983). The role of communication in decision-making groups: A functional perspective. In M. S. Mander (Ed.), Communication in transition: Issues and debates in current research (pp. 168-185). New York:

Praeger.

Gouran, D. S., & Hirokawa, R. Y. (1996). Functional theory and communication in decision-making and problem-solving groups: An expanded view. In R. Y.

Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and group decision making (2 nd ed., pp. 55-80). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gouran, D. S., Hirokawa, R. Y., Julian, K. M., & Leatham, G. B. (1993). The evolution and current status of the functional perspective on communication in decision-making and problem-solving groups. In S. A. Deetz (Ed.), Communication yearbook 16 (pp.

573-600). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Gouran, D. S., Hirokawa, R. Y., & Martz, A. E. (1986). A critical analysis of factors related to decisional processes involved in the Challenger disaster. Central States

Speech Journal , 37, 119-135.

Hewes, D. E. (1986). A socio-egocentric model of group decision-making. In R. Y.

Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and group decision-making (pp.

265-312). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hewes, D. E. (1996). Small group communication may not influence decision making:

An amplification of socio-egocentric theory. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole

(Eds.), Communication and group decision making (2 nd

ed., pp. 179-212). Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

31

Hirokawa, R. Y. (1980). A comparative analysis of communication patterns within effective and ineffective decision-making groups. Communication Monographs, 47,

313-321

Hirokawa, R. Y. (1982). Group communication and problem-solving effectiveness I: A critical review of inconsistent findings . Communication Quarterly, 30 , 134-141.

Hirokawa, R. Y. (1983). Communication and problem-solving effectiveness II: An exploratory investigation of procedural functions. Western Journal of Speech

Communication, 47, 59-74.

Hirokawa, R. Y. (1985). Discussion procedures and decision-making performance: A test of a functional perspective. Human Communication Research, 12 , 203-224.

Hirokawa, R. Y. (1987). Why informed groups make faulty decisions: An investigation of possible interaction-based explanations. Small Group Behavior, 18 , 3-29.

Hirokawa, R. Y. (1988). Group communication and decision-making performance: A continued test of the functional perspective. Human Communication Research, 18,

487-515.

Hirokawa, R. Y. (1990). The role of communication in group decision-making efficacy:

A task-contingency perspective. Small Group Research, 21 , 190-204.

Hirokawa, R. Y., Erbert, Il, & Hurst, A. (1996). Communication and group decision making effectiveness. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and group decision making (2 nd

ed., pp. 269-300). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hirokawa, R. Y., Gouran, D. S., & Martz, A. E. (1988). Understanding the sources of faulty group decision making: A lesson from the Challenger disaster. Small Group

Behavior, 19 , 414-433.

32

Hirokawa, R. Y., Ice, R., & Cook, J. (1988). Preference for procedural order, discussion structure, and group decision performance. Communication Quarterly, 36 , 217-226.

Hirokawa, R. Y., & Johnston, D. D. (1989). Toward a general theory of group decision making: Development of an integrated model. Small Group Behavior, 20 , 500-524.

Hirokawa, R. Y., & Pace, R. (1983). A descriptive investigation of the possible communication-based reasons for effective and ineffective group decision-making.

Communication Monographs, 50 , 363-379.

Hirokawa, R. Y., & Rost, K. M. (1992). Effective group decision making in organizations:

Field test of the vigilant interaction theory. Management Communication Quarterly,

5, 267-288.

Hirokawa, R. Y., & Salazar, A. J. (1997). An integrated approach to communication and group decision making. In L. R. Frey & J. K Barge (Eds.), Managing group life:

Communicating in decision-making groups (pp. 156-181). Boston: Houghton-

Mifflin.

Hirokawa, R. Y., & Scheerhorn, D. R. (1986). Communication in faulty group decisionmaking. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and group decision-making (pp. 63-80). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hoffman, L. R., & Kleinman, G. B. (1994). Individual and group in group problem solving:

The valence model redressed. Human Communication Research, 21 , 36-59.

Hogg, M. A. (2002). Social identity. In M. R. Leary & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 462-479). New York: Guilford.

33

Hollingshead, A. B., & Brandon, D. P. (2002). Potential benefits of communication in transactive memory systems. Human Communication Research , 29 , 607-615.

Hollingshead, A. B., McGrath, J. E., & O’Connor, K. M. (1993). Group task performance and communication technology: A longitudinal study of computer-mediated versus face-to-face work groups. Small Group Research , 24 , 307-333.

Hollingshead, A. B., Wittenbaum, G. M., Paulus, P. B., Hirokawa, R. Y., Ancona, D. G.,

Peterson, R. S., Jehn, K. A., & Yoon, K. (2005). A look at groups from the functional perspective. In M. S. Poole & A. B. Hollingshead (Eds.), Theories of small groups: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 21-62). Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Jackson, J. M. (1987). Social impact theory: A social forces model of influence. In B.

Mullen & G. R. Goethals (Eds.), Theories of group behavior (pp. 111-124). New

York: Springer-Verlag.

Jackson, M. H., & Poole, M. S. (2003). Idea generation in naturally-occurring contexts:

Complex appropriation of a simple procedure. Human Communication Research, 29 ,

560-591.

Jarboe, S. (1999). Group communication and creativity processes. In L. R. Frey, D. S.

Gouran, & M. S. Poole (Eds.), The handbook of group communication theory and research (pp. 335-368). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Keyton, J., & Wall, V. D. (1989). SYMLOG: Theory and method for measuring group and organizational communication. Management Communication Quarterly, 2 , 544-567.

Latane, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36 , 343-356.

34

Latané, B. (1996). Strength from weakness: The fate of opinion minorities in spatially distributed groups. In E. H. Witte & J. H. Davis (Eds.), Understanding group behavior, Vol. 1 (pp. 193-219) Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Lesch, C. L. (1994). Observing theory in practice: Sustaining consciousness in a coven.

In L. R. Frey (Ed.), Group communication in context: Studies of natural groups (pp.

57-82). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lemus, D. R., & Seibold, D. R. (2004, February). Testing the predictive potential of argument structures in computer-mediated groups.

Presented at the annual meeting of the Western States Communication Association, Albuquerque, NM.

Lemus, D. R., Seibold, D. R., Flanagin, A. J., & Metzger, M. J. (2004). Argument in computer-mediated groups . Journal of Communication, 54 , 302-320.

Mackie, D. M. (1978). Systematic and nonsystematic processing of majority and minority persuasive communications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53 , 41-

52.

Martin, R., & Hewstone, M. (2007). Social-influence processes of control and change:

Conformity, obedience to authority, and innovation. In M. A. Hogg & J. Cooper

(Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 312-333). Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage Publications.

McGrath, J. E. (1991). Time, interaction, and performance (TIP): A theory of groups. Small

Group Research , 22 , 147-174.

McPhee, R., Myers, K., & Trethewey, A. (2006). On collective mind and conversational analysis: A response to Cooren. Management Communication Quarterly , 19 (3),

311-326.

35

McPhee, R. D., Poole, M. S., & Seibold, D. R. (1982). The valence model unveiled:

Critique and alternative formulation. In M. Burgoon (Ed.), Communication yearbook 5 (pp. 259-278). New Brunswick, NJ: International Communication

Association/Transaction Books.

Meyers, R. A. (1989a). Persuasive Arguments Theory: A test of assumptions. Human

Communication Research, 15, 357-381.

Meyers, R. A. (1989b). Testing Persuasive Arguments Theory's predictor model:

Alternative interactional accounts of group argument and influence. Communication

Monographs, 56, 112-132.

Meyers, R. A., & Brashers, D. E. (1998). Argument and group decision-making:

Explicating a process model and investigating the argument-outcome link.

Communication Monographs, 65 , 261-281.

Meyers, R. A., & Brashers, D. E. (1999). Influence processes in group interaction. In L. R.

Frey, D. S. Gouran, & M. S. Poole (Eds.), The handbook of group communication theory and research (pp. 288-312). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Meyers, R. A., Brashers, D. E., & Hanner, J. (2000). Majority/minority influence:

Identifying argumentative patterns and predicting argument-outcomes links. Journal of Communication, 50 , 3-30.

Meyers, R. A., Brashers, D. E., Winston, L., & Grob, L. (1997). Sex differences and group argument: A theoretical framework and empirical investigation. Communication

Studies, 48, 19-41.

36

Meyers, R. A. & Seibold, D. R. (1989). Assessing number of cognitive arguments as a predictor of group shifts: A test and alternative interactional explanation. In B.

Gronbeck (Ed.), Spheres of argument: Proceedings of the sixth SCA/AFA conference on argumentation (pp. 576-583). Annandale, VA: Speech Communication

Association.

Meyers, R. A., & Seibold, D. R. (1990). Perspectives on group argument: A critical review of persuasive arguments theory and an alternative structurational view. In J. Anderson

(Ed.), Communication yearbook 13 (pp. 268-302). Newbury Park, CA: Sage

Publications.

Meyers, R. A., & Seibold, D. R., & Brashers, D. (1991). Argument in initial group decision-making discussions: Refinement of a coding scheme and a descriptive quantitative analysis. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 55, 47-68.

Morris, A. W., Seibold, D. R., & Meyers, R. A. (1991). The influence of individual differences in message production on argumentation in group decision-making:

Theory development and propositions. In F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A.

Blair, & C. A. Willard (Eds.), Proceedings of the second international conference on argumentation (pp. 582-589). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: International Society for the Study of Argument.

Moscovici, S. (1980). Toward a theory of conversion behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.),

Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 13 (pp. 209-239). New York:

Academic Press.

Moscovici, S. (1985). Social influence and conformity. In G. Lindsey & E. Aronson

(Eds.), The handbook of social psychology, 3 rd

ed. (Vol. 2) (pp. 347-412).

37

New York: Random House.

Nemeth, C. (1986). Differential contributions of majority and minority influence.

Psychological Review, 93, 23-32.

Nemeth, C. (1995). Dissent as driving cognition, attitudes and judgements. Social

Cognition, 13 , 273-291.

Orlitzky, M., & Hirokawa, R. Y. (2001). To err is human, to correct for it divine: A metaanalysis of research testing the functional theory of group decision-making effectiveness. Small Group Research, 32 , 313-343.

Pavitt, C. (1993). Does communication matter in social influence during small group discussion? Five positions. Communication Studies, 44 , 216-227.

Pavitt, C. (1999). Theorizing about the group communication-leadership relationship:

Input-process-output and functional models. In L. R. Frey, D. S. Gouran, & M. S.

Poole (Eds.), The handbook of group communication theory and research (pp. 313-

334). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pérez, J. A., & Mugny, G. (1996). The conflict elaboration theory of social influence. In

E. H. Witte & J. H. Davis (Eds.), Understanding group behavior: Small group processes and interpersonal relations, Vol. 2 (pp. 191-210). Hillsdale, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Poole, M. S. (1999). Group communication theory. In L. R. Frey, D. S. Gouran, & M. S.

Poole (Eds.), The handbook of group communication theory and research (pp. 37-

70). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

38

Poole, M. S., & Baldwin, C. L. (1996). Developmental processes in group decision making.

In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and group decision making

(2 nd

ed., pp. 215-241). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Poole, M. S. & DeSanctis, G. (1990). Understanding the use of group decision support systems: The theory of adaptive structuration. In J. Fulk & C. Steinfield (Eds.),

Organizations and communication technology (pp.175-195). Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Poole, M. S. & DeSanctis, G. (1992). Microlevel structuration in computer-supported group decision-making. Human Communication Research, 19 , 5-49.

Poole, M. S., McPhee, R. D., & Seibold, D. R. (1982). A comparison of normative and interactional explanations of group decision-making: Social decision schemes versus valence distributions. Communication Monographs, 49 , 1-19.

Poole, M. S., Seibold, D. R., & McPhee, R. E. (1985). Group decision making as a structurational process. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 71 , 74-102.

Poole, M. S., Seibold, D. R., & McPhee, R. E. (1996). The structuration of group decisions. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole (Eds.), Communication and group decision making (2 nd ed., pp. 114-146). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Price, V., Cappella, J. N., & Nir, L. (2002). Does disagreement contribute to more deliberative opinion? Political Communication, 19 , 95-112.

Propp, K. M. (1997). Information utilization in small group decision making: A study of the evaluative interaction model. Small Group Research , 28 , 424-453.

Propp, K. M., & Nelson, D. (1996). Problem-solving performance in naturalistic groups:

The ecological validity of the functional perspective. Communication Studies, 47,

127-139.

39

Putnam, L. L., & Stohl, C. (1996). Bona fide groups: An alternative perspective for communication and small group decision making. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole

(Eds.) Communication and group decision making (pp. 147-178). Thousand Oaks,

CA: Sage.

Putnam, L. L., Van Hoeven, S. A., & Bullis, C. A. (1991). The role of rituals and fantasy themes in teachers’ bargaining.

Western Journal of Speech Communication, 55 , 85-

103.

Sahlins, M. (1987 ). Islands of history . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Salazar, A. J., Hirokawa, R. Y., Propp, K. M., Julian, K. M., & Leatham, G. B. (1994). In search of true causes: Examination of the effect of group potential and group interaction on decision performance. Human Communication Research , 20 , 529-559.

Seibold, D. R., Canary, D. J., & Tanita-Ratledge, N. (1983, November). Argument and group decision-making: Interim report on a structurational research program . Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Speech Communication Association,

Washington, DC.

Seibold, D. R., & Lemus, D. R. (2005). Argument quality in group deliberation: A structurational approach and quality of argument index. In C. A. Willard (Ed.).

Critical problems in argumentation (pp. 203-215). Washington, DC: National

Communication Association.

Seibold, D. R., McPhee, R. D., Poole, M. S. Tanita, N. E., & Canary, D. J. (1981).

Argument, group influence, and decision outcomes. In C. Ziegelmueller & J. Rhodes

(Eds.), Dimensions of argument: Proceedings of the second SCA/AFA summer

40 conference on argumentation (pp. 663-692). Annandale, VA: Speech

Communication Association.

Stasser, G., Vaughan, S. I., & Stewart, D. D. (2000). Pooling unshared information: The benefits of knowing how access to information is distributed among group members.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 82 , 102-116.

Stohl, C., & Holmes, M. E. (1993). A functional perspective for bona fide groups. In S. A.

Deetz (Ed.), Communication yearbook 16 (pp. 601-614). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behavior. Social Science Information , 13 ,

65-93.

Tajfel, H. (1979). Individuals and groups in social psychology. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology , 18 , 183-190.

Tanford, S., & Penrod, S. (1984). Social influence model: A formal integration of research on majority and minority influence processes.

Psychological Bulletin, 95 , 189-225.

Tschan, F. (1995). Communication enhances small group performance if it conforms to task requirements: The concept of ideal communication cycles. Basic and Applied

Social Psychology, 17 , 371-393.

Turner, J. C. (1975). Social comparison and social identity: Some prospects for intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology , 5, 5-34.

Waldeck, J. J., Shepard, C. A., Teitelbaum, J., Farrar, W. J., & Seibold, D. R. (2002). New directions for functional, symbolic convergence, structurational, and bona fide groups perspectives of group communication. In L. R. Frey (Ed.), New directions in group communication (pp. 3-23). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Wegner, D. M., Erber, R., & Raymond, P. (1991). Transactive memory in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 , 923-929.

Weick, K. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Weick, K., & Roberts, K. (1993). Collective mind in organizations: Heedful interrelating on flight decks. Administrative Science Quarterly , 38 , 357-381.

Wittenbaum, G. M. (2002). Putting communication into the study of group memory.

Human Communication Research , 29 , 616-623.

Zajonc, R. B. (1965b). Social facilitation. Science , 149 , 269-274.

41