the subtitling of TV news reports from Northern Ireland

advertisement

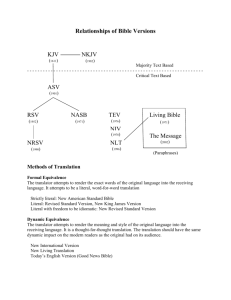

EQUIVALENCE IN THE SUBTITLING OF DANISH TELEVISION NEWS REPORTS FROM NORTHERN IRELAND Billy O'Shea Introduction If TV subtitles are the most read translations in Denmark,1 then subtitles for television news broadcasts are probably the most read translations of all. They deserve, therefore, to be treated seriously. In this article, I will argue that subtitles are translations in their own right - a fact which is occasionally disputed - and therefore, that translation theory can be properly applied to an analysis of subtitles for television news. Like many emigrés, I sometimes find it hard to recognise my own country in news broadcasts. My countrymen are translated into foreigners, who say strange things and whose statements lack coherence. The world of values which gives meaning to their utterances rarely survives the transition to a sound bite in another language. I will discuss whether this is inevitable, or whether it is possible to achieve a greater degree of understanding - the unquantifiable factor that Eugene Nida calls 'dynamic equivalence' - in transforming Irish speech into Danish news subtitles. Theoretical perspectives. Obtaining a qualitive measure of translation has always been problematic. Translation being a process governed by choice, it is impossible to arrive at the 'correct' translation of a source text. What, then, is a good translation, what is it that makes one translation better than another? The idea of fidelity to the source text is clearly insufficient in itself, in that exaggerated fidelity to souce text semantics distorts at times the author's intended meaning, making 'la belle infidèle' the better translation -an example being the translation of idiomatic phrases and culturally specific references, which, if rendered too literally, may prove incomprehensible to the target audience.2 (Nida (1964) cites such biblical examples as "gird up the loins of your mind", the meaning of which might be better conveyed for the general public by a phrase such as "get ready in your thinking".3 For an audience of theologians or Hebrew scholars, however, it is obvious that the first version is preferable.) The primary choice faced by the translator, then, is the extent to which the translation should be free or literal. This question, whether to favour the letter or the spirit of the source text, has been characterised by some theorists as a choice between 'author-centered' and 'reader-centered' translation strategies. These terms, however, could be considered misleading, given that both literal and free translations are produced with particular groups of readers in mind, and that both attempt, in some respect, to communicate the author's intentions. The actual contrast between the two approaches arises more from structural and connotative differences between source and target languages than from a simple choice between author or audience orientation. Peter Newmark therefore prefers the terms semantic and communicative translation (Newmark 1988:Chap.5). However, this runs into the same objection, since 'semantic' translation is nothing but an attempt to be more communicative to a given audience (those concerned with legal documents, for example). In as much as all competent translations ultimately aspire to be faithful to the author's intentions, the real determining factor concerning the degree to which translations are inclined to be free or literal must be the audience for which they are intended. The recent tendency, therefore, has been to move away from the text-centered idea of 'fidelity' (whether to letter or spirit), towards the more audience-centered concept of 'equivalence of effect'. In the words of Alexander Souter: "Our ideal in translation is to produce on the minds of our readers as nearly as possible the same effect as was produced by the original on its readers" (quoted in Nida 1964:164). This translation strategy, roughly corresponding to Newmark's 'communicative translation', is that which Nida terms dynamic equivalence (Nida 1964:159). It is obviously a relative term: a translation which approximates dynamically equivalence for one audience will not do so for another, even within language groups. Despite the flexibility of the concept, however, it nevertheless presents us with a range of problems. First of all, how can any translator possibly gauge the effect that the source text had on its readers' minds? In the case of the above-quoted Hebrew text, for example, a very considerable leap of the imagination is required. Even in contemporary texts, such an approach, to be successful, presupposes an extremely thorough knowledge of both subject and target cultures. Secondly, with regard to the target audience, the task may simply be impossible. Cultures, as well as languages, may be so much at variance that no such 'similar effect' can be produced. As Hjørnager Pedersen observes: "Dynamic equivalence is also, however, an awkward thing to deal with. The difficulty, as Arnold has already pointed out, lies in ascertaining the effect that was actually produced upon the source language audience, and, one might add, in establishing in a sufficiently precise and subtle manner the effect upon the target language audience. Naturally, one cannot in any strict sense speak of achieving the same effect in the target language as in the source language, when both audience and message are different in source and target language..." (Hjørnager Pedersen 1979:73, my translation) Even words or phrases that are readily translatable on the semantic level may possess a range of resonances and associations in the source culture that simply cannot be reproduced in the target culture. In the context of TV subtitling, Luyken, Reid and Herbst quote as an example the phrase "You musn't forget: I went to a public school, of course", and remark: "Even if a suitable translation could be found, no Language Transfer could ever render all the emotional associations linked with the idea of the public school in England (single-sex education, monastic life, separation from parents, sports and, not so long ago, corporal punishment)" (Luyken, Reid & Herbst 1991). And indeed, none of the Danish semantic equivalents of 'public school', kostskole, betalingsskole, privatskole, carries anything like this range of connotative implications. These objections have led certain theorists to reject the idea of dynamic equivalence and in some cases even formal equivalence - as being impossible.4 Some, like Newmark, prefer more pragmatic measures of translation quality, such as adequacy or functionality.5 However, it may be that they are being misled by the term equivalence itself, which, as Hatim and Mason point out: "...implies that equivalence is an achievable goal, as if there was such a thing as a formally or dynamically equivalent targetlanguage version of a source-language text" (Hatim & Mason 1990:8). If the idea of equivalence is to be understood as perfect human communication across a language barrier, then it is clearly impossible. But, as Steiner - in my view correctly - points out, all human communication is characterised by the same problem of achieving equivalence of effect, in that no two persons share exactly the same background or use symbols in precisely the same way (Steiner 1975:250). If equivalence, therefore, is impossible in translation, it is equally so in conversation. Human communication is an imperfect process. These difficulties notwithstanding, translation is both a reality and a necessity of modern life. Instead of declaring it to be impossible, therefore, we may be better advised to study translations as de facto cultural artifacts - just as studying the flight of the bumble bee may prove more fruitful for the biologist than for the engineer. This is the perspective adopted by Gideon Toury, for whom translations are to be regarded as: "facts of target cultures; on occasion facts of a special status, sometimes even constituting identifiable (sub-)systems of their own, but of the target culture in any event" (Toury 1995:29). Toury, while retaining the idea of equivalence as a central concept, opts for a qualititive measure along two axes, with 'adequacy' being the measure of a formally equivalent translation, while 'acceptability' governs those that are dynamically equivalent, most translations falling somewhere between the two. With regard to acceptability, Toury points out that since translations are always artifacts of the target culture, they are governed by norms operating within that culture. (A translation of the Old Testament stressing the polydeism of the ancient Hebrews would scarcely find favour in a Christian society, for example.) The translator, via the feedback he receives from the target culture as to the acceptability of his work, becomes to some degree socialised into producing translations that fit into the target culture's world-view. This does however beg the question as to whether norms should be allowed to exert such an influence. Toury admits of the possibility of 'deviant translations', and comments: "The price for selecting this option may be as low as a (culturally determined) need to submit the end product to revision. However, it may also be far more severe, to the point of taking away one's earned recognition as a translator, which is precisely why non-normative behaviour tends to be the exception, in actual practice. On the other hand, in retrospect, deviant instances of behaviour may be found to have effected changes in the very system. This is why they constitute an important field of study, as long as they are regarded as what they have really been and are not put indiscriminately into one's basket with all the rest. Implied are intriguing questions such as who is 'allowed' by a culture to introduce changes and under what circumstances such changes may be expected to occur and/or be accepted." (Toury 1995:64) Deviancy is, of course, only possible if the translator is conscious of the operation of such social norms. In most cases, however, these norms will have been internalised to such a degree that they merely inform the translator's view of reality. Toury's comment has weighty implications for, amongst other things, the translation of journalism, and it is an idea that I will be returning to later in this article. Bearing in mind the above discussion and, especially, the limitations of the concept of equivalence, the theoretical perspective which seems to me to be the most cogent and useful for the issue in hand is that defined by Nida: "No longer is it sufficient merely to to compare the two forms M1 (message in the source language) and M2 (message in the receptor language). rather, one must determine the extent to which the typical receptors of M2 really understand the message in a manner substantially equivalent, though never identical, with the manner in which the original receptors comprehended the first message (M1). " (Nida 1975:95) I choose, however, to regard Nida's definition as a guide to analysis rather than as an objective measure of translational quality, which in my view is unattainable. Nida's definition should also be modified by Toury's caveat that "it is norms that determine the (type and extent of) equivalence manifested by actual translations" (Toury 1995:61). Subtitling for Danish television news Before we can apply translation theory to the process of subtitling, we have to decide whether subtitling for TV news is in fact translation. The answer is not as straightforward as it may appear, given that some subtitlers maintain that subtitling is a skill which is separate and distinct from that of translation.6 The reasons normally given are: 1. Translation normally concerns written source and target texts. Interlingual subtitling is a 'diagonal' process, from the spoken to the written word (Gottlieb 1994b). 2. Subtitling is part of a polysemiotic communication, in which other visual and aural clues play an important role. The subtitler must harmonise the words written on the screen with these other factors in order to produce a total 'message'. Written translation, by contrast, is monosemiotic, using only one channel of communication (Gottlieb 1996). 3. Subtitling normally involves substantial compression of the original verbal message, with a consequent information loss or 'information entropy' (Tveit 1994). Compression is not a necessary or normal facet of written translation. 4. Constraints of subtitle exposure time, together with the absence of footnotes, etc., mean that the subtitler has very little room for maneuver with regard to explaining unfamiliar or culturally specific references to the viewer (explicitation). Written translation is not subject to these constraints (Carstensen 1992:78-84). I will only attempt to deal with these points insofar as they have a bearing on the subtitling of television news. Point (1) appears to be little more than a quibble over definitions, there being no reason why we cannot define 'translation' as any inter-human communication across a language barrier; including, for example, sign language for the deaf and interpreting. Written translation and subtitling are thus special categories of translation, but neither, obviously, has a monopoly on the term. (We may even go as far as Steiner, and extend the definition of translational activity to encompass all human communication.) Regarding point (2), while it is true that subtitles normally comprise only one element in a total visual-aural 'message', subtitles for television news are something of a special case, in that most of the visual elements, not having been planned in advance by a director, are mere 'noise' compared to the verbal content, which is consequently given very high priority. Factors such as body language, background events, etc. are or should be still relevant, however - if the subtitler has the opportunity to see the video recordings, which is not always the case, as the subtitler must sometimes work from an audio tape only.7 Points (3) and (4) can be taken together. Given present standards of exposure time (in Denmark, about six seconds for a full two-line subtitle), some compression of the original verbal content is unavoidable. In the case of TV news, however, such compression forms, as it were, a kind of contract between translator and audience. Few viewers would feel themselves well served if the subtitler were to reproduce all the hesitations and repetions of normal unrehearsed speech. What the viewer wants is the substance of the message, its most essential content. The resultant loss of information does not in itself disqualify subtitling as a form of translation, for, as Nida remarks: "all types of translation involve loss of information, addition of information, and/or skewing of information"(Nida 1975:27). The question of interest is not whether information is lost, but which information, and why. The news subtitler must decide how much of the original discourse is information and how much is merely 'noise'. Information is, however, a relative and not an absolute term: hesitations, for example, would, as mentioned above, normally be considered superfluous, but there are obviously times when a significant hesitation is information. It should also be noted that equivalence, or the lack of it, is not necessarily a function of the amount of information transferred to the target language: a term such as 'guerillas' can for example be translated as 'terrorists' - or vice versa - without any measurable loss of information having taken place. A valid criticism of subtitling, as opposed to written translation, is the fact that constraints of subtitle exposure time also severely limit the amount of information that can be added to the original message in the form of explicitation. The TV news subtitler rarely has enough exposure time available to be able to make clear the meaning of an unfamiliar term or acronym. Furthermore, subtitlers may themselves be unacquainted with the situational, cultural, historical or political background to the utterance (Tveit 1994:2). For explicitation, the subtitler must rely on the journalists and presenters, who - ideally - will have explained any unfamiliar material before it appears in the subtitles. However, it should be noted that this implies that subtitling for TV news is not an entirely independent process of translation, but is 'locked into' the journalistic processing of news as a whole - a point to be discussed later in this article. Finally - and perhaps must crucially - the definitions of translation employed by such theorists as Nida, Toury and Steiner are more than broad enough to encompass the subtitling of TV news as a translational activity. Ergo: TV news subtitling is translation, and we can proceed. The functions of news subtitling in Danish state television The examples of subtitled news reports which I will be examining here have been gleaned from the archives of Danmarks Radio, the Danish state national broadcasting station.8 Subtitles in DR TV's news broadcasts serve a dual purpose: to translate items containing foreign language speech (interlingual subtitling) and as an aid to comprehension for the deaf and hard of hearing (intralingual subtitling). These two functions are not separated (as is the case at some other TV-stations), but are presented in parallel, and are produced by the same subtitlers.9 While the interlingual subtitles are the most relevant for the purposes of this article, the intralingual subtitling function should be noted, in that it establishes an intimate link between the various journalists' Danish-language input to their reports, and the subtitling of any foreign-language sequences those reports may contain. Subtitlers will, for the sake of consistency, tend to utilise the same terms in both kinds of subtitling, and will thus be influenced by the journalist's choice of equivalent term. This, together with other opportunities to consult with the journalists, will tend to influence the translation towards dynamic equivalence, in that a consensus can, potentially, be arrived at concerning the most appropriate Danish equivalent expression. Such consensus-seeking practice, however, also implies that it is here that the operation of any social norms is most likely to become visible. On the other hand, the practice of consultation with journalists has become somewhat rarer than it has been in the past, and in addition, subtitlers are sometimes required, often under great pressure of time, to translate mere isolated fragments of taped speech that have been pulled out of context. On these occasions, the translation is more likely to assume the character of formal equivalence, in that the subtitler, not knowing the background to the situation, will tend to stick to stricter semantic equivalents. . Subtitled reports from Northern Ireland during 1996 The source material Since the concept of equivalence has a cultural as well as a linguistic dimension, I have chosen to examine news reports from a culture with which I am familiar, namely that of my own country, Ireland. I have further narrowed the field by confining my research to reports from Northern Ireland during the period January - December 1996. Reporting from Northern Ireland, like that from other parts of the world, tends to be sporadic and event-centered, leading to a clustering effect. During 1996, such 'report clusters' arose during the following periods: 1. The London Docklands bomb and the end of the IRA ceasefire (9th-12th February). 2. Orange Order marches, riots at Drumcree, and the Enniskillen bombing (8th-15th July). 3. Bombing of Lisburn army base and British government reaction (9th and 10th October). In all, twenty-two news broadcasts have been examined. I will not attempt to comprehensively analyse all of the subtitles involved, most of which were uncontroversial, but merely highlight areas that seem to me to be of interest, or that seem to present difficulties, in the light of Nida's concept of dynamic equivalence and Toury's perspective on the operation of social norms. Given the pressures under which news subtitlers must work, it hardly seems fair to criticise them for occasional imprecision, and indeed that is not my purpose here. What I am interested in is not the odd 'glitch' but the way in which certain terms and concepts achieve, or fail to achieve, equivalence when subtitled in Danish. Nida's definition of equivalence implies that anything that influences the target audience's understanding of a translation changes, in effect, the translation itself. However, the question "What can influence the Danish viewers' understanding of these subtitles?" is clearly a question without boundaries, and since an infinite question begets an infinite answer, I have confined my analysis to three areas that I feel to be relevant and of interest, namely: frames, the religious model, and terminological problems. Frames We normally think of the subtitling of foreign-language news items as a purely linguistic process: from language A to language B. But items of foreign news are also 'translated' by a host of other factors: picture and sound editing, music and effects, captions, commentary and the juxtaposition of other news items all have a bearing on the way that an item of foreign news is understood, and therefore also influence the way that the subtitles are interpreted. To give an example from the material at hand: on July 14th, 1996 a subtitled comment from the Northern Irish political activist David Irvine was broadcast on the 21.00 hrs DR news bulletin; Irvine was described in the presenter's introduction as "den politiske leder af UVF, det protestantiske modstykke til IRA." [the political leader of the UVF, the protestant counterpart to the IRA]. On the 8th of October, however, a comment from the same man was prefaced by the words "Moderate protestanter opfordrer loyalisterne til at lade være med at gengælde gårsdagens bombeattentat." [Moderate protestants are calling on the loyalists not to retaliate for yesterday's bomb attack.] What Irvine actually said on the latter occasion was: "What I would say to them is : don't do it! Don't do what your enemies want you to do." The interpretation of these words by the viewer - however they are translated - obviously depends greatly on whether Irvine is seen as a political moderate opposed to violence, or as the leader of a paramilitary organisation! On another occasion (14th July 21.00 hrs), a subtitled comment from Dick Spring, the Irish foreign minister, was captioned as coming from 'John Bruton, irsk statsminister' [John Bruton, Irish prime minister]. A small error, perhaps, but a potentially significant one, given that Bruton and Spring are the leaders of two separate parties that have often in the past disagreed on the question of Northern Ireland policy. Captions are normally produced by production assistants or graphic artists, not subtitlers, but clearly, ascribing a translated statement to the wrong person has the potential to entirely change the way that it is understood. The understanding of a translation - and therefore, the translation itself - can thus be altered by factors exogenous to both the source and target text. In the context of TV news subtitling, there can therefore only exist a total process of translation - which implies that subtitling, as a translational activity, cannot be seen in isolation to its frame: the processing and presentation of the news as a whole. For this reason, I include in the following not only interlingual subtitles, but occasionally also relevant intralingual subtitles and the introductory remarks of presenters and journalists. The religious model -an example of social norms influencing translation? One of the most striking aspects of the 1996 reports from Northern Ireland is the way in which terms such as 'nationalists' and 'unionists' are almost always translated as, respectively, katolikker [catholics] and protestanter [protestants]. Unionister [unionists] does not appear in interlingual subtitles, but was used once in subtitles for the deaf on the 12th Feb. (18.00 hrs bulletin), as was republikaner [republicans]. The term nationalister [nationalists] was used in introductory remarks on the 14th July (21.00 hrs bulletin), though unfortunately referring to unionists rather than those known in Northern Ireland as nationalists: "De seneste dages uro blussede op da politiet tillod protestantiske nationalister at marchere gennem katolske kvarterer" [The unrest of the last few days ignited when police permitted protestant nationalists to march through catholic areas]. In all other instances, the two sides are distinguished exclusively in religious terms. This, of course, is a phenomenon that can be observed not just in Danish television news but everywhere in the Danish media in reports from Northern Ireland. In Denmark, the conflict in Northern Ireland is viewed as one which takes place between 'catholics' on one side and 'protestants' on the other. Catholics seek a united Ireland, because southern Ireland is catholic. Protestants wish to remain part of the United Kingdom, because Britain is protestant. This perception of the Northern Irish conflict is so universal that one rarely meets a Dane with any other interpretation. The most obvious problem with this model is that it is not shared by the two Northern Irish communities themselves, who perceive the conflict as one that takes place, not between protestants and catholics but between 'unionists' and 'nationalists'. About 30% of nationalists would also describe themselves as republicans, meaning that they support the IRA or one of its splinter groups. The remainder, who do not support the IRA, mostly vote for the Social Democratic Party. The IRA for their part do not see themselves as being at war with 'protestants', but rather with the British government and the British Army, in a continuation of the antiimperialist struggle that resulted in independence for what is now the Irish Republic. (The republican movement which has evolved into the IRA was founded by Wolfe Tone, a protestant Irish nationalist, and in its early years was dominated by protestant leaders and intellectuals, many of whom were executed by the British and are now regarded by the IRA as martyrs to the nationalist cause.) Unionists are all those - catholics as well as protestants - who want Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom; their enemies are therefore not 'catholics' but the IRA, whom they see as anti-democratic terrorists. Militant unionists, who believe that the IRA must be fought by guerilla methods, are known as loyalists. The fact that most nationalists in Northern Ireland are catholics, while most unionists are protestants, is a historical accident engendered by, amongst other things, the partitioning of the island in 1922. It is true that the assumption by some people within Northern Ireland that 'all catholics are republicans', or 'all protestants are loyalists' has led to sectarian attacks, but these are comparatively rare, and are generally condemned by politicians as well as paramilitaries from both sides. It should also be noted that even such sectarian attacks are ultimately motivated by politics rather than religion. The Northern Ireland conflict, in other words, has in the final analysis very little - if anything - to do with religion. Does it matter? After all, using terms like nationalister and unionister would be sure to cause a certain amount of confusion, and, as Jytte Heine writes: "...it is precisely in the area of news broadcasting that neutral, easily understood expressions, which the viewer will not find puzzling, are the most appropriate" (Heine 1994:240, my translation).Using religious, rather than political, labels makes the conflict easier for Danish viewers to understand, say subtitlers.10 But the problem with the terms katolikker and protestanter is that they do not merely distinguish the two communities, they also imply an explanation for the conflict which in the eyes of most Irish people on both sides of the political divide would be considered manifestly false, namely that it springs from religious intolerance.11 Using terms such as det katolske IRA [the catholic IRA] (8th Oct. 18.00 hrs) or UVF, det protestantiske modstykke til IRA [the UVF, the protestant counterpart to the IRA] (14th July 21.00 hrs) is therefore directly misleading. By Nida's definition of dynamic equivalence, then, these terms fail the test, in that they do not convey to the viewers a message which is "substantially equivalent" to the way in which the terms 'nationalist' and 'unionist' (or 'republican' and 'loyalist') would be understood in Ireland. A concrete illustration is available to us in the subtitled comments of the aforementioned David Irvine of the loyalist UVF, broadcast on the 14th of July. Asked to comment on the previous days' confrontations, Irvine said: "The violent republican movement had the choice to light the touchpaper or not to light the touchpaper. And they chose to light the touchpaper." This was subtitled on the 18.00 hrs bulletin as: "IRA havde muligheden for at vælge freden, men de valgte volden." [The IRA had the chance to choose peace, but they chose violence.] Apart from the minor criticism that 'the republican movement' encompasses more than just the IRA, this seems a good, reasonably equivalent, rendering of Irvine's statement. However, on the 21.00 hrs bulletin, the same comment was subtitled quite differently as: "De voldelige katolikker havde valget. Men de valgte at puste til ilden." [The violent catholics had the choice. But they chose to blow on the fire.] At puste til ilden [to blow on the fire] is a good approximation of the English phrase 'to light the touchpaper', but Irvine's condemnation of a particular political movement has been turned into an expression of religious bigotry. Another illustration of the religious model at work is afforded by the reports following the explosion of a bomb at a hotel in Enniskillen on the 13th July. No organisation claimed responsibility, and the reason for the attack has remained something of a mystery. A wedding reception - protestant - had been held in the hotel the day before the attack, but that fact was not generally considered relevant in the British or Irish media. The Danish presenter's introductory remarks, however, on the 14th July (18.00 hrs.), stated: "Volden hærger igen i Nordirland. I nat sprang en bilbombe udenfor et hotel, hvor en protestantisk familie holdt bryllupsreception." [Violence rages again in Northern Ireland. Last night a car bomb exploded outside a hotel in which a protestant family were holding a wedding reception.] The reference to the wedding reception was dropped in later DR reports. The bomb was, however, presumed to originate from the nationalist side, in that loyalist paramilitaries rarely use the car-bomb tactic. Following this event, on July 16th, DR's Northern Ireland correspondent put the following question to Nelson McCausland of the Ulster Unionist party: "Should we then expect a reaction from the other side, the protestant side?" Subtitled: "Skal vi så forvente at protestanterne gør gengæld?" [Should we expect, then, that the protestants will retaliate?] McCausland's reply was: "I certainly hope that there will not be a response from the loyalist paramilitaries." Subtitled: "Jeg håber ikke de loyalistiske paramilitære grupper gør gengæld." [I hope that the loyalist paramilitary groups will not retaliate.] The subtitled translations here are entirely competent, but there is a subtext: McCausland's reply is a correction of the journalist's perception of 'the other side'. The response, says McCausland, if it comes, will not be from 'the protestants', but from the loyalist paramilitaries. It is beyond the scope of this article to speculate as to why the religious model is so widely adopted in the Danish media as an explanation of the Northern Ireland situation. It may be that it reflects a Danish perception of violent conflicts as essentially hysterical and incomprehensible. At any rate, its near-universality qualifies it, in my view, as a social norm of the kind which, as Toury warns, can exert a powerful - if unconscious - influence upon translations. Terminological problems The Northern Ireland conflict abounds in terms for which there is no immediately obvious Danish equivalent. 'Paramilitaries', meaning the armed republican and loyalist groups, often seems to give rise to problems. Paramilitære grupper [paramilitary groups], as quoted above, is formally equivalent, but uninformative, and therefore less equivalent in the dynamic sense. Halvmilitære [semimilitary] (subtitles for the deaf, 8th Oct. 21.00 hrs) makes one wonder what the remainder is like. Undergrundshær [underground army] (13th July 21.00 hrs) has been used for the IRA but seems inappropriate for smaller groups. Probably the best Danish equivalent would be milits [militia], but while this term is often used in reporting from the Middle East, I have never seen it applied in a Northern Ireland context. The protestant12 Orange Order is usually rendered as Orangeordenen, but occasionally as Oranjeordenen (e.g. 12th July 18.00 hrs). The orthographical variation probably depends on whether the word 'orange' in this context is understood as deriving from the colour orange, or alternatively from the title of William of Orange (later King William III of England), who is known as Wilhelm af Oranjen in Danish. While it is true that the Orange Order was established to commemorate William of Orange, whose title derives from the name of a town in southern France, the actual colour of orange was adopted by William as the symbol of his royal house, and has always been closely associated with Irish protestantism. Hence Orangeordenen is probably the better version. Some confusion also arises as to whether the inhabitants of Northern Ireland are to be referred to as British or Irish: although Northern Ireland is referred to as den britiske provins [the British province] (10th July 18.00 hrs & 12th July 21.00 hrs), the term briterne [the British] seems to refer only to the inhabitants of the island of Britain, e.g. ifølge protestanterne har briterne overgivet sig til IRA, [according to the protestants, the British have surrendered to the IRA] (subtitles for the deaf, 8th July 18.00 hrs). Strictly speaking, all the inhabitants of Northern Ireland are Irish, whether or not they profess loyalty to Britain. The official title of the British state is The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: Northern Ireland is thus a part of the United Kingdom, but not of Britain. Nationalists in Northern Ireland have always regarded themselves as being Irish without qualification, but on the other side, the question of identity is more complex. A poll carried out by Richard Rose of Strathclyde University in 1968 - before the onset of the present troubles - revealed that as many as 20% of protestants thought of themselves as Irish, while 39% preferred to be called British, and 32% thought of themselves as citizens of Ulster (i.e. Northern Ireland). By 1989 these figures had shifted considerably, with 68% of protestants now calling themselves 'British', 26% 'Ulster' or 'Northern Irish', and only 3% 'Irish' (Bowyer Bell 1996:117). Probably the best compromise in Danish, then, as far as political positions are concerned, would be nordirske unionister/nationalister [Northern Irish unionists/nationalists]. As regards the status of the province itself: if one is referring to the de facto political situation, then the use of the term den britiske provins [the British province] may be justified, but translators should be aware that such a choice has political connotations (as does the use of 'Londonderry' in preference to 'Derry'), and that, in geographical, legal and historical terms, Northern Ireland is not a British province, but an Irish province under British rule. Finally, there is the problem of what to call the conflict. Borgerkrig [civil war] (subtitles for the deaf, 9th July 18.00 hrs) gives the impression of a two-sided internecine affair, with the British, presumably, acting as passive observers or as peace-seeking mediators. Few in Northern Ireland -or indeed in Britain- would share this perception. It also, to some extent, overdramatises the conflict, given that the number of deaths from political violence in the province has, despite everything, never exceeded the number of people killed in traffic accidents. I have never seen the term 'civil war' used in the British or Irish media in connection with Northern Ireland, except as a warning of possible future developments. Uroligheder [disturbances, riots] is used somewhat more frequently in the source material (e.g. in virtually every news broadcast from the 8th to the 14th July), presumably as an analogue to the usual Irish term, 'the troubles'. But 'troubles', in Ireland, has political connotations which uroligheder does not convey. The term, as used in Ireland, originally referred to the IRA war of independence, 1918-21, and the southern Irish civil war that followed. It thus denotes a military guerilla campaign, not civil disorder. This can lead to misunderstandings, such as in the following statement from David Trimble, leader of the Ulster Unionist party, broadcast on the 14th of July at 18.00 hrs: "There is an agenda that's been working here by Sinn Féin-IRA, to try to plunge Northern Ireland back into the troubles, and doesn't it underline how foolish the decisions were, that brought this about?" This statement was subtitled as follows: 1. Sinn Fein og IRAs dagsorden har været at kaste Nordirland [Sinn Fein and the IRA's agenda has been to cast Northern Ireland -] 2. - ud i uroligheder. [- into riots.] 3. Det understreger hvor tåbeligt det var med den her beslutning. [This underlines the foolishness of this decision.] Trimble's comment came after a police decision to allow the Orange Order to march through a nationalist area, a decision which resulted in riots throughout the province. The subtitler understands Trimble's use of the word 'troubles' to refer to these riots (uroligheder), and consequently interprets the second half of the statement as a criticism of the police decision. In fact, Trimble is not criticising the police. On the contrary, he is accusing the IRA and Sinn Féin (which he sees as one organisation) of cynically using the ceasefire as a political tactic, before finding an excuse to re-start their military campaign. 'Foolish decisions' refers, therefore, not to the police decision, but to the various decisions made by the British government to allow negotiations with Sinn Féin to take place during the peace process, thus permitting republicans to gain a position of relative influence. For unionists like Trimble, the IRA are terrorists with whom one should never negotiate. In this instance, insufficient background knowledge has forced the subtitler to seek refuge in formal, rather than dynamic, equivalence. The result is a translation which conveys very little of Trimble's intended meaning. As to what to call the Northern Irish hostilities, I can only - somewhat lamely suggest strid [strife] or konflikt [conflict], which at least have the advantage of flexibility, and do not suggest, as does borgerkrig [civil war], that the problem is an internal Northern Irish affair without active British involvement. Conclusion Most of the subtitles I examined in preparing this article were as close to both formal and dynamic equivalence as one could reasonably expect them to be. These I have of course not analysed here, for the simple reason that they are nothing like as interesting as those that are problematic. The latter, on the other hand, have proved a stimulating object of study. As I stated at the beginning, there is no such thing as a correct translation - although some may be less incorrect than others - and neither is there any truly objective measure of translational quality. I have utilised the idea of dynamic equivalence, as developed by Nida and Toury, to help guide my thinking on the subject, but in the end my assessment of the degree of equivalence achieved by this selection of DR TV news subtitles cannot be other than subjective. Dynamic equivalence is a difficult standard to aspire to the context of Northern Ireland, a part of the linguistic world where codes and subtexts sometimes make even apparently transparent statements difficult to interpret. Formal equivalence, however, is not a sufficient guide to the subtitling of statements of local origin, since even ordinary English words may in this region have specialised usages or coded meanings. Some knowledge of the complex cultural background to the conflict and of its historical origin is required, if subtitles for Danish viewers are to attain approximate dynamic equivalence. Nida's definition of equivalence also implies that the process of translation is not merely linguistic, but extends to include a range of factors exogenous to both the source and the target text. In the context of news subtitling, one of these factors is, I have suggested, the processing and presentation of the news item itself, which can affect the interpretation of subtitles to the extent of becoming a part of the translation. Following Toury, I have also attempted to detect the effect of social norms upon the translational process. I believe that the 'religious model' which apparently colours the perceptions of Danish journalists, subtitlers and viewers concerning Northern Ireland, is an example of one such norm. I do not underestimate the difficulties of avoiding controversial translations; in an area as sensitive as Northern Ireland, where language is itself political, any translation will probably give offence to someone. But one should at least try to avoid translations which are likely to offend all sides. It may be that the religious model, as claimed, makes the conflict easier for Danes to understand; on the other hand, it is the task of TV news broadcasts to attempt to explain the world, not to explain it away. As an explanation, the religious model is untenable; as a guide to translation, it is grossly misleading. It should be abandoned. The subtitler, however, cannot know everything about everything. It should be the responsibility of the relevant journalists to ensure that the subtitler has sufficient background information to be able to create subtitles which possess some measure of dynamic equivalence. Without such consultation, the translations produced by subtitlers will tend towards formal or semantic equivalence, which as we have seen, is sometimes no translation at all. Works cited: Bowyer Bell, J. 1996. Back to the Future: the Protestants and a United Ireland. Dublin: Poolbeg. Gottlieb, Henrik. 1994 a. Tekstning: synkron billedemedieoversættelse; Danske Afhandlinger om Oversættelse nr.5. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen. Gottlieb, Henrik. 1994 b. Subtitling: Diagonal Translation, Perspectives. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. Gottlieb, Henrik. 1996. Tekstning, et polysemiotisk puslespil. In: Frandsen, Finn (Ed.) Medier og Sprog. Ålborg: Ålborg Universitetsforlag. Hatim, Basil and Mason, Ian. 1990. Discourse and the Translator. London:Longman. Heine, Jytte. 1994. TV-tekster til tiden: oversættelse og tekstning af nyheder, Hermes 13. Hjørnager Pedersen, Viggo. 1979. Oversættelsesteori. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen. Koller, Werner.1995. The Concept of Equivalence and the Object of Translation Studies, Target 7:2. Luyken, G-M., Reid, H. and Herbst, T. 1991. Overcoming Language Barriers in Television. Manchester: European Institute for the Media. Newmark, Peter.1988. A Textbook of Translation. Hemel Hempstead: Prentice Hall. Nida, Eugene A. 1964. Toward a Science of Translating. Leiden: Brill. Nida, Eugene A. 1975. Language Structure and Translation:Essays. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Reid, Helene.1990. Literature on the Screen. In: Westerweel & D'haen (Ed.) Something Understood: studies in Anglo-Dutch literary translation. Amsterdam: DQR studies in literature nr.5, Rodopi. Steiner, George.1975. After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. London: Oxford University Press. Toury, Gideon. 1995. Descriptive Translation Studies and beyond. Amsterdam:John Betjeman. Tveit, J.E. 1994. Subtitling and Information Entropy. In: Brikke, Magnar (Ed.) Applications and Implications of Current LSP Research. Bergen: Proceedings of LSP conference, Bergen 1993, vol.2. Whorf, B.L. 1956. Language, Thought and Reality. Cambridge, Mass.:MIT. Footnotes: 1.. Gottlieb 1996:11. 2.. I use the term 'target audience' here in preference to 'target culture'. Few translations - not even TV subtitles - are comprehensible to, or accessible by, an entire culture. In most cases the translator has a specific sub-group in mind. 3.. Nida 1964:170-171. 4.. The most famous example being the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, according to which differing language structures may in and of themselves preclude the translation of even certain kinds of factual statement. See Whorf 1956. 5.. Newmark 1988:2 Hjørnager Pedersen 1979:15 6.. Gottlieb 1994a:43-45 Reid 1990:1 7.. Heine 1994:242 : "...in news subtitling the visual elements play a subordinate role, in that we (subtitlers), as already mentioned, rarely have time to see the video before transmission". (My translation). This situation has, however, improved somewhat since 1994. 8.. Only the news broadcasts of the principal national, non-commercial channel, Danmarks Radio channel 1 (DR1), have been examined. For a description of the actual news subtitling process at Danmarks Radio, see Heine 1994. 9.. On 1st August 1996, intralingual subtitles were moved to teletext and no longer appear on the normal broadcast screen, although they are still composed by the same subtitlers that produce interlingual subtitles. The intralingual subtitles (subtitles for the deaf) quoted in this article are those that appeared before August 1996, and, inasmuch as they essentially represent a condensed version of the original manuscript, the terms employed in them should be understood as originating with the journalist concerned rather than the subtitler. 10.. Conversations with Jytte Heine and Henrik Gottlieb. 11.. It is of course perfectly possible to maintain that religion is what the conflict is really about, even if the participants themselves deny it: a kind of marxist 'false consciousness' could be at work. But in that case the alternative model should be better able to account for the actual events than the explanations of the people directly involved. This is not the case with, for example, the bomb attacks of 1996, which were directed against the London Docklands area, a hotel in Enniskillen and the Lisburn headquarters of the British Army in Northern Ireland. Apart from the Enniskillen bombing - which remains unexplained - the choice of British commercial and military targets reflects the IRA's perception that they are at war with the British government and its military presence in Northern Ireland. 12.. The Orange Order is - apart from the churches themselves - the only major organisation in Northern Ireland with a specifically sectarian character. Membership is only available to protestants.