Using ActiveX Controls

advertisement

Using ActiveX Controls

1. An ActiveX control is really a separate program which runs separately

but manages the appearance of a window within your program. It is

registered in the Windows Registry as an ActiveX control.

2. Visual Studio checks the Registry and allows you to put ActiveX controls

in your program using the dialog editor, just like ordinary controls.

3. MFC supports the communication between your program and the

ActiveX control, so that you don’t have to add code for that purpose.

This makes using ActiveX controls in an MFC program as easy as using

ordinary controls.

4. The interface to an ActiveX control is precisely defined. It consists of

properties and methods. Properties have symbolic names that are

matched to integer indices. For each property XXX, there is a SetXXX

method and a GetXXX method. For example, for the BackColor

property, there would be a SetBackColor method and a GetBackColor

method. A method, like a function, has a symbolic name, required

parameters, and a return value.

5. In your program, a C++ class will represent the control, and the member

functions of that class call the methods of the control.

6. A program using an ActiveX control is called a “container”. The control

does not send messages to the container like an ordinary control would

do. Instead it “fires events”. An event is a function defined in the

container; to “fire” an event means to call this function. For example,

there might be an event called Click which the control fires when the

mouse is clicked in its window.

7. The code for an ActiveX control is usually in a DLL, but the filename

extension is often .ocx. A single such file can contain several controls.

These files are typically kept in the system directory so that the system

can find them easily.

8. Before an ActiveX control can be used it must be registered. Actually, it

registers itself when a certain function exported by the DLL is called.

This can be done using the Regsvr32 utility that comes with Windows,

mentioning the control name on the command line.

Now let’s build a program that uses an ActiveX control. Create a new MFC

project. Make it SDI, and in the application properties, go to Generated

Classes and make the view class inherit from CFormView. That way our

main window will be a dialog (“form”). Once the project is created, go to

Resource View and click your Form dialog to open it in the resource editor.

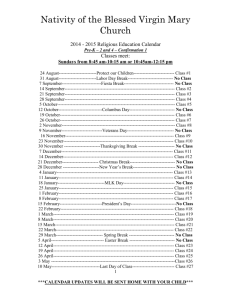

We want to put a Calendar Control on the form. Don’t be confused by the

fact that there is something labeled Month Calendar Control on the Dialog

Editor toolbar. That is a different control, not a Calendar Control 10.0. To

get a Calendar Control 10.0, right click your dialog and choose Insert

ActiveX Control. Select a Calendar Control 10.0. It will be created at such

a tiny size that it is almost unrecognizable. You have to make it bigger—

then you will see this:

You can build and run this program now. The calendar works—it is a

complete program in its own right.

Some of the control’s properties are design-time properties. That means you

can change them at compile time. Right click your control and select

Properties. You’ll see a property sheet like this one:

Just like with any other control you can specify the ID number. Try

changing some of the other properties and then running your program.

Even though this control looks attractive, and even though you can

customize its size and appearance, it’s not much use so far—you need to

make your program communicate with it, for example to let the user choose

a date on which he will send you money. Communication with the control

can go two ways: Either the control can fire an event, which your program

can handle as it would handle a message, or, if you want to tell the control

something, you call one of its methods. Let’s do the former first, as it is

easier.

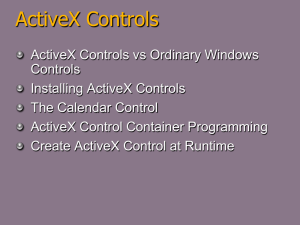

Class Wizard lets you map ActiveX control events the same way you map

Windows messages and commands from controls. Right-click your view

class in Class View, select Properties, and click the button with the lightning

flash icon, whose tool-tip says Events. You should see a list with an item

for your calendar control. Expand that node and you should see this:

This shows the events you can “map”. You do this exactly as you would

“map” a message. Let’s add some very simple handlers just to see if the

control is communicating to our program. The following handlers just make

“beeps” of different pitches and durations when the user changes the month

or the year.

void CActiveXDemoView::AfterUpdateCalendar1()

{ Beep(256,100);

}

void CActiveXDemoView::NewMonthCalendar1()

{ Beep(512,100);

}

void CActiveXDemoView::NewYearCalendar1()

{ Beep(512,300);

}

What user actions fire which of these events?

If we want to tell the calendar control something (e.g. to set the date to a

dynamically generated value), then we need to have a class corresponding to

the calendar control. This can be done through Project | Add Class, but

there is an easier way: just right-click the control and choose Add variable.

You can add a variable of category control. This can be used to call the

methods of the control, just as you called ListBox::AddString earlier in the

semester. Try that. Afterwards, you can check that a new class has been

added to your project:

Instead of calling some of the calendar controls methods, we will move on to

another example:

Adding a Web Browser to your program

A calendar is fine, but how about adding a Web browser to your program?

Go back to the dialog editor and right-click, and choose Insert ActiveX

Control. This time, select Microsoft Web Browser. Like the calendar, it

first appears at a ridiculously small size, and in the upper left. You will have

to enlarge your dialog to make room for a reasonably large browser control.

1. Right-click your dialog, and add a member variable m_browser

corresponding to this class. (It's a member of the view class.)

2. Add the following code to OnInitialUpdate:

COleVariant noArg;

m_browser.Navigate("www.cs.sjsu.edu/faculty/beeson",

&noArg,&noArg,&noArg,&noArg);

This sets an initial URL for the browser.

3. Run the program: the contents of the specified page are displayed (if

you have an Internet connection).

4. You have the functionality of Internet Explorer available. To make a real

web browser, you could add an edit box where the user can type a URL and

a Go button that calls the Navigate method as above. You could use an

array or a CArray to hold the recently visited locations, and add Back and

Forward buttons that would call Navigate to the next or previous element of

this array. Would you like a browser that lets you view two URLs

simultaneously in two different windows? Just add two of these browser

controls to your program.

Working with WebBrowser Events

The WebBrowser control fires a number of different events to notify an

application of user- and browserr-generated activity. The events are

implemented using the DWebBrowserEvents2 interface. When the control

is about to navigate to a new location, it fires a BeforeNavigate2 event that

specifies the URL or path of the new location and any other data that will be

transmitted to the Internet server through the HTTP transaction. The data

can include the HTTP header, HTTP post data, and the URL of the referrer.

BeforeNavigate2 also includes a cancel flag that you can set to FALSE to

cancel the navigation. The WebBrowser control fires the

NavigateComplete2 event after it has navigated to a new location. This

event includes the same information as BeforeNavigate2, but

NavigateComplete2 does not include the cancel flag.

When the WebBrowser control is about to begin a download operation, it

fires the DownloadBegin event. The control fires a number of

ProgressChange events as the operation progresses, and then it fires the

DownloadComplete event after completing the operation. Applications

typically use these three events to indicate the progress of the download

operation, often by displaying a progress bar. An application would show the

progress bar in response to DownloadBegin, update the progress bar in

response to ProgressChange, and hide it in response to

DownloadComplete. When an application calls the Navigate method with

the Flags parameter set to navOpenInNewWindow, the WebBrowser control

fires the NewWindow2 event before navigating to the new location. The

event includes information about the new location and a flag that indicates

whether the application or the control is to create the new window. Set this

flag to TRUE if your application will create the window or to FALSE if the

WebBrowser control should create it.

Some Final Remarks

If you have a modal dialog containing an ActiveX control, you may want to

lock it in memory so it doesn’t have to be loaded each time the modal dialog

appears. This is done by adding the following line of code to your

overridden OnInitDialog after the base class call:

AfxOleLockControl(m_calendar.GetClsid()); here m_calendar is a member

variable of your dialog class corresponding to the control, that is, its type is

the C++ wrapper class for the control. This line of code is only meant to

prevent delay in the appearance of the dialog due to loading the control into

memory again.

ActiveX controls can be added to an HTML file, in which case Internet

Explorer will use them. Netscape with a suitable plugin can do so also. But

they will only work on a Windows machine, so it’s not much use if you

want to make a web page that Mac and Unix users can see.

If you want to use an ActiveX control, such as the Web Browser control, in

your view window rather than in a dialog box, then you must add the control

dynamically. That’s where you would use Project | Add Class to create a

class corresponding to your control. Add a data member of this type to the

class corresponding to the window you want to contain the control. Map the

WM_CREATE message for the container window and call the control

class’s Create function. In the container window class, you must manually

add the event message handlers and prototypes, including the

BEGIN_EVENTSINK_MAP and END_EVENTSINK_MAP macros (which

are written for you automatically when you add an ActiveX control to a

dialog box). This is a difficult business and not for the weak or the fainthearted.