Comments on “El Niño: Catastrophe or Opportunity”

advertisement

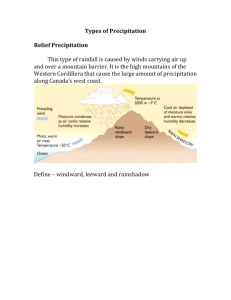

Various Paragraphs George J. Huffman 13 August 2008 Acronyms GPCP SG 1DD TMPA TRMM MW IR HQ VAR TMPA-RT 3B40RT 3B41RT PPS PMM GPM 3B42RT TOVAS ASCII GDISC CoCoRaHS Global Precipitation Climatology Project Satellite-Gauge monthly combined precip product One Degree Daily precip product TRMM Multi-satellite Precipitation Analysis Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission microwave (sensor channel) infrared (sensor channel) High-Quality (MW) precip estimate Variable Rainrate (IR) precip estimate Real-Time version of the TRMM Multi-satellite Precipitation Analysis PPS identifier for HQ product in real time PPS identifier for VAR product in real time Precipitation Processing System Precipitation Measuring Missions Global Precipitation Measurement project PPS identifier for TMPA-RT combined MW-IR product TRMM Observations Visualization and Analysis System Text, or character data Goddard Data and Information Services Center Community Cooperative Rain, Hail, and Snow network Satellites Estimate Precip, Rather than Measuring It Although we sometimes say that particular satellites measure precipitation, more precisely satellites measure the radiant energy in various parts of the electromagnetic spectrum that allow scientists to estimate precipitation. As the energy upwells from the Earth’s surface through the atmosphere, it is modified by the gases, aerosols, clouds, and precipitation that make up the atmosphere, and the satellite channels are chosen to be sensitive to various combinations of those things. Some channels are “window” channels, relatively insensitive to gasses and aerosols and mostly responding to the highest-elevation object that the satellite sees, either a dense cloud or the surface. Examples include visible and infrared channels. Other channels sense the precipitation particles. In some cases, the channels respond to the emission of additional radiant energy by the liquid precipitation, while others detect reductions in the upwelling radiant energy due to icy precipitation particles scattering away the upwelling energy. Examples include microwave channels. The microwave sensors are more accurate, but fly only on satellites that have “low” altitude orbits and therefore provide only occasional snapshots of any particular spot on Earth. These and other issues prevent completely accurate estimates of precipitation from satellites and emphasize the need to consider satellite results only as estimates. What Does a Typical Global Precipitation Picture Look Like? 1 <this could point to the lower “week accumulation image” on trmm.gsfc.nasa.gov> At the largest scales, namely global images averaged over weeks or longer, the precipitation takes on a fairly stable pattern. There is a narrow band of nearly continuous moderate-to-heavy precipitation that encircles the Earth fairly close to the Equator, the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone. At slightly higher latitudes there tend to be large areas of very light precipitation, located in the “subtropical high pressure” centers. In mid-latitudes the precipitation is again systematically higher, due to the repetitive occurrence of low pressure centers and frontal systems in the “storm tracks”. Animations of average monthly data around the annual cycle reveal systematic shifts of these basic features with the seasons, principally showing that the precipitation maxima tend to move north-south as the Sun moves north-south during the year. The largest departure from this usual picture occurs in the Equatorial Pacific Ocean in El Niño and La Niño events, which occur every 3-7 years and take most of a year to run their course. <this could point to the upper “3-hr image” on trmm.gsfc.nasa.gov> Moving to successively shorter time scales reveals that precipitation occurs in discrete patterns, as you would expect from your personal experience, which makes it hard to infer the broadscale patterns that become apparent with enough time averaging. In the tropics, the systems tend to appear as relatively shapeless blobs, except for the occasional tropical cyclone. At higher latitudes the precipitation is frequently organized into lines and arcs in the vicinity of fronts and low pressure systems. Even at higher latitudes, in the absence of strong dynamical organization strong convection will also appear in blobs. At time scales shorter than a day, one sees the typical cycles of precipitation that occur over the course of the day. These diurnal cycles occur more or less strongly depending on location and season, but land areas generally have stronger diurnal cycles than the oceans. Tropical and subtropical coastal areas tend to show land/sea breeze effects that are coupled. When you view the image loop of 3-hourly precipitation on trmm.gsfc.nasa.gov, the “flashing” of individual features partly represents real short-term variability, but mostly it arises from disagreements among the satellite estimates. Sources of Error and Typical Errors Errors arise from four main sources in rainfall estimation. First, the satellite data themselves can have errors. Typically, the channels are well-enough calibrated that other errors dominate the error budget, but rarely there are processing problems that can result in substantial artifacts. In addition, there are a variety of transmission, reception, and archival issues that can impact the quality of the estimates. Due to its near-real-time production, the TMPA-RT is created and posted without human intervention, so data errors have the potential for appearing in the precipitation products. Glaring errors are corrected when observed, sometimes by recomputing with corrected data, and sometimes by simply dropping the offending data from the system. The second source of error arises from limitations in the information content of the available satellite channels. That is, the observations for any particular channel, or even all the channels taken together, do not adequately provide information to unambiguously determine the precipitation. Furthermore, in specific situations, such as land surfaces and icy or snow-covered surfaces, some or most of the available channels stop providing useful information. In part, this deficiency arises because essentially all of the sensors are “passive”, simply recording the upwelling radiant energy. “Active” sensors, which send out a very specific signal and record its return, provide much better information, but are too complex and power-intensive to have seen 2 routine use. A few active sensors are being flown for research purposes, including the TRMM Precipitation Radar and several lidar packages. This problem can only be addressed by adding better sensors on future satellite mission. For example, the upcoming GPM satellite will include channels that observe the atmosphere, but not the surface. Another aspect of the limited information content in sensor data is that each sensor footprint yields values averaged over some spatial area. For precipitation-related sensors, these footprints range in size from 5 to 50 km in diameter. The sensor provides no information on smaller-sized regions within the footprint, thereby establishing a lower limit on the size of features that data users can study. Here again, the solution is equipping future satellites with finer-resolution sensors. The third source of error arises from inaccuracies in the algorithms that translate that information into precipitation estimates. To a certain extent this issue is intertwined with the limitations of the sensors, but even when the theoretical use of the channel is clear, it is not always possible to make full use of the sensor’s capabilities due to computation expense or lack of necessary additional data. Finally, errors in the combined precipitation estimates arise due to gaps between observations by the satellites. The sensors that provide the best channels for estimating precipitation only fly on low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellites, each of which can only provide one or two snapshots a day of any particular place on Earth. Even taking the entire constellation of such satellites together, one can only expect a higher-quality estimate every three hours or less often. Geosynchronous-Earth orbit (GEO) satellites provide observations every 15-30 minutes over much of the Earth, but the sensors that they carry provide precipitation estimates that are relatively inaccurate on a footprint-by-footprint basis. In the short and intermediate term, most improvements in precipitation estimates will come by attacking the last two problems. As improvements in processing are introduced, users should expect to occasionally see new versions of the precipitation products. The data producers strive to inform users of such updates and are typically interested in hearing about specific problems in the data, even if no changes can be made in the processing for several years. Over land, errors generally are higher over coastal areas and regions covered by snow or ice. Precipitation that occurs in relatively shallow clouds will likely have more errors, and this includes precipitation enhancement and suppression due to wind flow over hills, mountains, and valleys (orographic precipitation). Light and short-lived precipitation in general are harder for the products to correctly depict. 3