Enthalpy of Reaction

advertisement

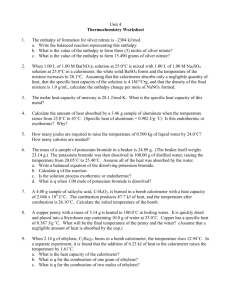

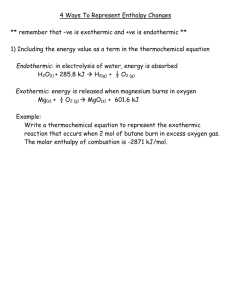

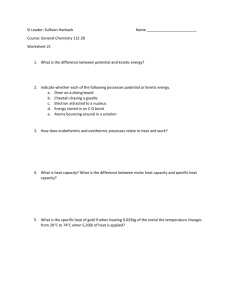

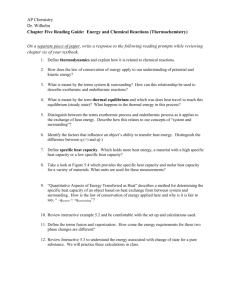

Enthalpy of Reaction The objective of this experiment is to determine the enthalpy of reaction of an acid with base. The method employed is a general one. PRINCIPLES The amount of heat that is absorbed or liberated in a physical or chemical change can be measured in a well-insulated vessel called a calorimeter. You will use a simple calorimeter, Fig. l, that is suitable for measuring heat changes in solution. Calorimetry is based on the principle that the observed temperature change which results from a chemical reaction can be simulated with an electrical heater. The electrical measurements of current (I), heater resistance (R), and duration (t) of heating make it possible to calculate the amount of heat equivalent to that produced by the chemical change; the formula I2Rt is used, as derived in the following section. The use of weighed quantities of reactants makes it possible to calculate the enthalpy change per mole. In this experiment you will obtain the enthalpy change for the reaction: HA(aq) + OH-(aq) → A-(aq) + H2O(l) (I) Since you will be working with solid acids, the desired quantity will be obtained by measuring the enthalpy of net reaction for the solid acid with the reaction: HA(s) + OH-(aq) → A-(aq) + H2O(l) (II) and the enthalpy of solution with the reaction: HA(s) → HA(aq) (III) In measuring ∆H(II) and ∆H(III), the solid acid is added to NaOH solution and water, respectively. The required ∆H(I) is obtained by combining the two measured quantities: ∆H(I) = ∆H(II) - ∆H(III) In addition, you will attempt to establish a relationship between the enthalpy change, ∆H(I), and a structural or chemical property of the acid. Measurement is one component of experimental science, but interpretation of the results is just as important. Electrical Energy 1 Electrical current, measured in amperes, is the time rate of flow of electrical charge (coulombs); by definition, amperes coulombs sec onds The common relationships between electrical potential in volts (V), current in amperes (I), and resistance in ohms (R) is known as Ohm’s Law, V = IR Electrical energy is given by coulombs Energy volts amperes sec onds volts sec onds sec onds E = V I t volt coulombs By definition: l joule = l volt coulomb By combining these laws and definitions, we get Electrical energy = I2 Rt joules Figure 1. Calorimeter and power supply. The Calorimeter 2 The calorimeter operation is outlined below with reference to Fig. 1. The 400-ml beaker is surrounded by Styrofoam insulation to minimize heat loss or gain through the walls. The transparent Lucite cover (C) serves as a support for the electrical immersion heater (H). It also has three holes: two large and one small. The stainless-steel temperature probe (T) in inserted into the small hole. One large hole provides an opening for the purpose of adding solid reagents, and the other permits the insertion of a thermistor temperature probe which is no longer used. The solution is stirred by a Teflon-covered magnet (M) which is rotated by a motor-driven magnet (M'). The temperature is measured by means of a platinum resistor, which is located at the end of the thermometer probe. The device depends on the nearly linear dependence of the probe’s resistance with temperature. It will determine temperature changes to a precision of 0.001°C and, with calibration, absolute temperature to 0.05°C. Figure 1 shows a greatly simplified circuit that indicates how the electrical heating is measured and controlled. The double-pole switch (S) controls two things simultaneously: the timer (W), and the constant current source, represented by the battery (B) and the resistance (Z), that supplies the current that flows through the heater (H). The current (I) which flows through the heater is read from the ammeter (A). The resistance of Z is chosen so as to give a current of about 1 ampere through the circuit. The heater resistance has already been measured on another instrument and its value in ohms will be shown on a label on the Lucite cover (C). The timer will give you, to the nearest 0.1 sec, the length of time that the current passes through the heater. You will take temperature measurements at 30-sec intervals before, during, and after the electrical heating process, and for this you will use a small electronic timer externally mounted to the power supply. Treatment of the Data 3 Experimentally, it is almost impossible to duplicate exactly the temperature change from a chemical reaction by electrical heating. Instead, it is customary to calibrate the calorimeter; that is, find the number of joules of electrical energy required to raise the temperature of the reaction mixture and calorimeter by 1.000°C. This calibration is made by dividing the total electrical energy input (Ec) by the temperature rise (∆Tc) resulting from the input, to give the calibration factor Ec/Tc, joules per degree. Then, to obtain the energy resulting from the chemical change, all you have to do is multiply this calibration factor by the observed temperature change (∆Tx) for the reaction. E Energy of the Chemical Change = c Tx Tc Because the calorimeter is not perfectly insulated, it slowly loses or gains heat depending on whether it is warmer or cooler than its surroundings. A second source of small temperature changes is the mechanical work performed by the stirrer. Hence, a constant stirring rate in each run is essential. An accurate determination of the temperature changes for both the reaction and the heater requires that some allowance be made for this slow rate of cooling or heating that occurs in the calorimeter when it is not in use. Therefore, before mixing the reactants (or turning on the heater) a continuous record is made for several minutes of the very slow rate of temperature change while the calorimeter liquid is being stirred; then, after mixing the reactants (or turning off the heater) another record is kept for several minutes of the very slow rate of temperature change of the reaction mixture. A plot of typical data for a complete heat of solution and calibration experiment is shown in Fig. 2. The linear sections of the plot before and after the major temperature changes are extrapolated forward and backward in time. One vertical line is drawn at a time corresponding to 15 sec after the addition of the salt, and another at the midpoint of the time interval between turning the heater on and 30 sec after turning the heater off. ∆Tx is then taken as the vertical distance between the points at which the first vertical line intersects the lines extrapolated before and after adding the salt; ∆Tc is taken as the vertical distance between the points at which the second vertical line intersects the lines extrapolated before and after using the heater. Since ∆Tx and ∆Tc should be estimated to the nearest 0.001°C, the graph must be carefully plotted on a generously large scale. 4 2.200 salt added 2.100 2.000 heater off 1.900 Temperature 1.800 Tc (vertical line is drawn at midpoint between turning heater on and 30 seconds after turning it off) 1.700 1.600 Tx (vertical line is drawn 15 seconds after salt addition) 1.500 1.400 1.300 1.200 heater on 1.100 1.000 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Time, min Figure 2. Plot of sample data for a heat-of-solution and calibration experiment. In this case a salt with endothermic enthalpy of solution is dissolved in water. Note that in order to obtain the data for the graph just described it is necessary to record the temperature as a function of actual time as measured on the external timer. In addition, in order to calculate the electrical energy dissipated in the calibration of the calorimeter, the length of time during which the current flows must be obtained independently from the calorimeter timer. 5 EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE 1. Getting Started (a) Select a partner with whom you want to work on the lab. (b) Obtain one solid acid per pair from the desiccator and transfer it to your desiccator. Record the identity of the acid in your notebooks. (c) Decide which partner will be finding the enthalpy of solution (dissolving the solid acid in water) and which will be finding the net enthalpy (dissolving the solid acid in 0.2 M NaOH). 2. Weighing the Solid Acid and Solvent (a) Put a weighing boat on the analytical balance and tare the balance to zero. (b) The table below gives the approximate values of how much solid acid is needed in each run. The amounts have been adjusted to yield temperature changes (mostly) between 0.5°C and 1.0°C. In the resulting concentration range, the dependence of the molar enthalpy on concentration is very small and can be ignored. Add the appropriate amount of acid to the weighing and accurately record the mass in your notebook. Put the weighing boat containing the sample into a second desiccator for transport to your calorimeter. In weighing out the sample, break up any lumps. Moles of Solid Acid to Use in Each Run Enthalpy of Solution Enthalpy of Net Reaction (Acid & Water) (Acid & Base) NaHCO3 0.036 mol 0.036 mol KHSO4 0.029 mol 0.015 mol HIO3 0.028 mol 0.017 mol Na2HPO4 0.028 mol 0.014 mol KH2PO4 0.037 mol 0.007 mol (c) (d) Put a dry 400-ml beaker containing a magnetic stirring bar on the top loading balance in the laboratory and tare the balance to zero. Add approximately 250 ml distilled water or base to the beaker using your 250-ml volumetric flask. With a dropper adjust the weight of the water or base to 250.0 g. 6 3. Preparing the Apparatus for Measurements (a) Prior to each run, measure the room air temperature using the mercury thermometer in the room. You can also use the digital thermometer but the probe must be dry. Expect fluctuations in this result due to the air currents. A value to ± 0.2°C is sufficient. (b) Place the Lucite cover with the thermometer probe in place over the cavity of the Styrofoam block on the magnetic stirrer. Remove the cover, place the beaker into the cavity, and put the Lucite cover on the beaker. Turn on the magnetic stirrer so as to give vigorous but not turbulent stirring. The stirring rate must be constant during a single run. Check that the back (c) (d) two-pronged plug for the heater is plugged into the DC power supply. The orientation of the plug in the socket is not important. Why? Turn on the power supply with power switch located on the lower left hand corner of the supply. The power on pilot light must light. Preparation of the solvent. You need to adjust the starting temperature of the solvent as discussed below. If the temperature of the solvent is not in the desired range, turn the switch of the heating circuit ON and heat the water until the temperature does lie in this range. Then turn the heating circuit OFF, and press the reset button beside the timer display. (i) (ii) Case of measurement of the enthalpy of net reaction: Prechilled base is provided; heat it up so that its temperature is about 0.50.7°C below the room temperature reading. Case of measurement of the enthalpy of solution: Except in the case of Na2HPO4, heat the water so that its temperature is about 0.3-0.5°C above the room temperature reading. In the case of Na2HPO4, heat the water so that it is 0.5-0.7°C below the room temperature reading. 4. Establishing the Initial Temperature Commence a 15-20 minute series of temperature measurements taken in unbroken succession (through step 7 below) at 30-sec intervals; use the external timer for determining the 30-sec intervals when the digital thermometer is read. 5. Introducing the Salt Sample When it is clear from the measurements of about the first 3-5 minutes that the temperature is changing only slowly and in a regular manner, prepare for the 7 addition of the solid acid as follows. Immediately following one of the 30-sec temperature observations: (a) (b) (c) (d) Remove the weighed acid sample from the desiccator. Insert the dry powder funnel into the larger hole at the front of the Lucite cover. Do not insert the funnel prior to this in order to avoid the possibility of moistening the funnel with spray generated by stirring. Poise the solid acid over the funnel with one hand and hold the brush in the other hand. At the time normally scheduled for making the next 30-sec temperature observation, pour the solid acid into the tunnel brushing any remaining acid from the boat and funnel into the beaker. Do not try to read the (e) temperature of the solution at the instant you add the sample; merely record which of the 30-sec points was used for addition to the sample Check to make sure that the magnetic stirrer is spinning. If it is not, turn down the speed control until it begins spinning again and then readjust the speed to give vigorous stirring. 6. Re-establishing a Steady-State Temperature Again read the temperature at 30-sec intervals, even though the first reading after adding the salt is not a very stable one. The rate of solution varies considerably from sample to sample. Once the sample as dissolved as evidenced by a small rate of temperature change, record the temperature at 30-sec intervals for an additional 3-5 minutes. 7. Calibration of the Calorimeter When the temperature baseline has been established, take a thermometer reading at a regular 30-sec interval and simultaneously turn on the heater. (Before you turn on the heater, make sure that the timer has been reset to zero.). Let the current flow until the solution temperature had been raised by about 0.6-0.7°, then turn the heater OFF. During the heating period continue to take temperature measurements at the scheduled 30-sec intervals but realize that they can be only approximate, since the temperature will be changing rather rapidly. Also during the heating period while the current is flowing, tap the ammeter gently and record the ammeter reading to the nearest 0.00l amp. After turning off the heater, continue to record the temperature at 30-sec 8 intervals for a period of 3-5 minutes after the temperature stops rising. Record, to the nearest 0.l sec, the reading on the timer. Record the resistance of the heater used in your calorimeter; it is given on a label on the Lucite cover. 8. Repeating the Determination (a) Remove the Lucite cover, rinse the heater and thermometer probe, and gently dry them with a tissue. Put the cover over the cavity. Empty the beaker, being careful not to lose the stirring bar. Remove your beaker from the Styrofoam block. Rinse the beaker and stirring bar, and wipe dry with a Kimwipe. (b) (c) Repeat the experiment twice more, starting each time with a dry beaker. When you are finished turn off the power supply and the digital thermometer. Thoroughly rinse the temperature sensor, heating element, and beaker before you leave. CALCULATIONS Part I. Personal Measurements A. Plot, on a piece of millimeter graph paper provided with the lab manual, your measurements of temperature vs. time for the solution or net reaction of the acid. Use a separate piece of graph paper for each repetition of the experiment. B. For the process that you studied, i.e. the solid acid dissolving or water or reacting with base, calculate the enthalpy change per mole of solute for each run, the mean value, the standard deviation, and the relative 95% confidence interval of the mean expressed as parts per hundred (%). Since you used the same amount of solvent in each run, the calibration factors, EC/∆TC, should be nearly constant. C. By subtracting the mean enthalpy change of solution from the mean net enthalpy change for the reaction with base, you and your partner should be able to determine the solution-phase enthalpy of reaction for your acid mixed with base (∆H(I) = ∆H(II) - ∆H(III)). D. Include the graphs of your runs with your report. 9 Part II. Derivation of Your QSAR The lab instructor will quickly grade the report submitted by each member of the group and provide via Email the pooled results to all members of the group as well of data for compounds not examined by the group. Use the full set of data including the data found in the lab manual to derive a QSAR. Complete the second page of the lab report and submit the full report in class on the Wednesday following acquisition of the data. The final task is the interpretation of your data and the data collected by the other groups of students. By examining the variation in the enthalpy change and the variation in other physical properties, you may discover a relation, i.e. a correlation, that will increase your understanding of the properties of acids and bases. Lord Kelvin argued that legitimate science must be quantitative and we shall follow his dictum in our discovery of a relationship. Our tool will be the method of least squares that was introduced at the start of the semester. If ∆H depends on a physical property X, then a least squares fit of ∆H, the dependent variable, to X, the independent, will be good. R2, the square of the correlation coefficient, will be our criterion for identifying a statistically significant relationship. A table of R2 as a function of confidence level (95% is normally used) and degrees of freedom (# data points - # parameters) is provided. Table of Critical Values of R2 Degrees of Freedom 90% Confidence Level 95% Confidence Level 1 0.976 0.994 2 0.810 0.903 3 0.648 0.771 4 0.531 0.658 5 0.448 0.569 6 0.386 0.500 7 0.339 0.446 8 9 10 0.301 0.271 0.247 0.399 0.362 0.332 10 Consider the case of 5 data points and 2 parameters, e.g. a slope and an intercept. We have 5 – 2 = 3 degrees of freedom and at the 95% confidence level, R2 must equal or exceed 0.771 or the proposed model must be rejected as unsupported by the data. Hence, if R2 were 0.875, we would accept the hypothesis that ∆H depends on property X; with R2 0f .650, we would reject the model. However, although R2 would be unacceptable with 3 degrees of freedom, it would be more than acceptable with 6! In numbers, there is strength! We note that the community of chemists that uses modeling and statistical methods in the design of new and more effective drugs insists that a data set contain at least 5 compounds. This approach, which is very productive, was developed at Pomona College by Professor Emeritus Corwin Hansch. The equation resulting from his powerful approach is called a QSAR for quantitative structure activity relationship. Hence we are asking you to develop a QSAR involving the enthalpy of reaction, ∆H(I). To this end, we have provided a tabulation of properties of the acids that you have studied. Many of those properties were calculated with Spartan, a modeling program that you will use this semester. You may wish to consider other properties and are invited to do so. We have supplemented the data with data for other acids so that your data set is large enough. Armed with this information, we invite you to develop your own QSAR for ∆H(I). You will identify a statistically significant relationship, i.e. which variables are correlated, but will also derive an equation, the mathematical relationship between the correlated variables. Be sure to include this equation with your report. Also submit all Excel output with your report sheet. 11 Selected Properties of Acids Acid ∆H(reaction) pKa qH qO qM rOH OH EPE cm-1 3833 kcal -58.9 kJ/mol -62.54 4.27 0.408 -0.665 0.724 Ǻ 0.991 -50.49 8.32 0.449 -0.726 0.518 0.974 3841 -54.8 HCO3- 10.33 0.408 -0.853 1.232 0.965 3469 -51.9 HSO4- 1.97 0.456 -0.812 1.875 0.967 3863 -20.9 HIO3 0.77 0.535 -0.720 1.233 0.974 3803 80.5 12.35 7.20 0.368 0.430 -0.897 -0.862 1.743 1.743 0.970 0.966 3784 3892 -144.5 -32.4 HC2O4 - HSeO3- 2- HPO4 H2PO4- ∆H is the enthalpy change for the removal of one proton qH is the partial charge on the acidic H atom qO is the partial charge on the O atom attached to the acidic hydrogen qM is the partial charge on the atom to which the OH group is attached rOH is the O-H bond length in Ǻngstrom OH is the vibrational frequency of the O-H bond stretch in cm-1 EPE is the energy of interaction at the site of the acidic proton with a test charge in kcal 12 NAME________________________________ Lab Section_____________ Calorimeter Number__________________ Acid_______________________ Date Report Submitted______________________ ENTHALPY OF REACTION 1. Personal Measurements: Your solvent: base or water (Circle one) Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 3 Weight of acid (g) __________ __________ _________ Weight of solvent (g) __________ __________ _________ Solution concentration (mol/kg of solvent) __________ __________ _________ ∆Tx caused by addition of acid (from graph) __________ __________ _________ ∆Tc caused by electrical heating (from graph) __________ __________ _________ Ammeter reading (amp) __________ __________ _________ t, time during which current passed (sec) __________ __________ _________ R, electrical resistance of heater (ohms) __________ __________ _________ Ec, electrical energy input __________ __________ _________ Calibration factor (Ec/∆Tc) __________ __________ _________ Enthalpy Change (J/g) __________ __________ _________ Enthalpy Change (kJ/mol) __________ __________ _________ Average enthalpy change (kJ/mol) ____________ Standard deviation ____________ Relative 95% confidence interval of the mean, % ____________ 13 2. Shared Data Your Acid __________ Mean Enthalpy Change of Solution (H/mole for equation III) __________ Mean Enthalpy Change for Solid + Base (H/mole for equation II) __________ Enthalpy Change of Reaction (H/mole for equation I) __________ Other Partners’ Results: Acid ∆H(equation I) __________ __________ __________ __________ __________ __________ 3. What relationship, if any, did you establish between ∆H(reaction) and the physical properties given? Provide your QSAR and the statistics supporting it. What does your QSAR tell you about the properties of acids? 4. Show sample calculations on the back side of this page. Attach a graph for each run. 14