Tuberculosis in Indonesia, Kraszewski

advertisement

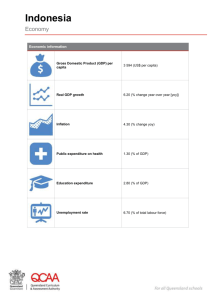

Angela Kraszewski Tuberculosis in Indonesia From: Secretary of Health, Indonesia To: Minister of Finance, Indonesia Introduction: Tuberculosis causes 91,000 adults to die every year, making it the leading cause of adult deaths in Indonesia.vii The incidence of TB is estimated to be 528,063 TB cases per year.i About 6,400 people in our country get drug-resistant TB every year and about 3% of those infected with HIV have active TB. Poverty being a contributing factor, TB largely affects the poor, the uninsured, those living in rural areas, those with weak immune systems, and those seeking health services from centers that do not treat TB with DOTS. TB causes ill health for a long period of time, keeps people from earning wages, causes them to spend large amounts on treatment, and leads many families into poverty.ii DOTS is a low cost approach to TB diagnosis and treatment that has been very successful, but needs to be expanded and implemented more effectively in the eastern regions of Indonesia and Sumatra, where the disease burden is highest.iv We must also pay special attention to the diagnosis and management of drug-resistant TB and to TB/HIV coinfection. Nature and Magnitude of the Problem: Indonesia has the third highest TB disease burden globally, behind India and China.vii TB is responsible for 6.3 percent of the total disease burden in Indonesia, compared with 3.2 percent in the Southeast Asian region.i As of 2008, the prevalence of TB in Indonesia was 253 cases per 100,000 people.vii According to WHO, there were 528,063 estimated new TB cases and a projected incidence rate of 102 new sputum smear-positive cases per 100,000 people in 2007.i TB control in Indonesia is difficult because of the challenge of treating and containing multidrug-resistant TB cases. The number of new sputum smear positive MDR TB patients in 2007 was about 2% of all cases, although about 20% of all retreated TB cases are MDR TB.i MDR TB is more expensive and difficult to treat exacerbating the problem. As of 2009, XDR TB has not appeared in Indonesia, but it still remains a huge threat.i The fact that HIV positive individuals are more susceptible to TB infection is another difficult obstacle in containment. In fact, more than 50% of individuals living with HIV die from TB infection. Although the national adult HIV prevalence is low at .6%, 3 percent of those newly infected with TB are HIV positive.i Affected Populations: The effect of TB is most prominent in marginalized groups including the poor, uninsured, individuals living in rural areas, women, and those that seek health services that do not use DOTS. In fact, 60% of the cases afflict the poor and poorly educated in our country.viii Children are more adversely affected because they are often overlooked and thus misdiagnosed and given poor treatment. About 70% of the TB cases affect those in the working, productive age group.vii Although the majority of the cases are still affecting individuals, ages 15 to 54 years, the trend of the TB epidemic is starting to shift toward the older age groups (55-64 years).vi Furthermore, the highest cases of TB mortality are among women of reproductive age, only exacerbating the deaths among this group from maternal mortality.viii There are also a number of regional differences of TB disease rates in Indonesia. About 60% of the population resides in Bali and Java but they have one of the lowest rates of TB 1 incidence and the most advanced system of health care delivery. In contrast, Sumatra has double the rate of TB and the eastern regions of Indonesia have four times the burden of TB because of the remote and hard to access areas and the limited number of healthcare workers.iv Risk Factors: The most important risk factors for developing TB are undernourishment, HIV and other immune-compromising diseases, living in crowded areas, poor health services, and exposure to a person with TB.ii A majority of these risk factors stem from poverty and poor health infrastructures. Poverty causes many people to be malnourished, which increases their chances of not being able to fight off the infection. Poor people also tend to live in crowded conditions, leading to an increased risk of TB infection. In addition, being immune-compromised also increases susceptibility to getting the disease. The growing number of MDR TB cases is largely due to TB patients that are inadequately treatedi, and the contribution of default on treatment and the misuse of second-line drugs in hospitals is worsening the drug-resistant TB problem.i Social and Economic Consequences: The social and economic costs of TB to families and Indonesia are very high because of its debilitating effects, the vast number of people with the disease, its long-course of ill-health, and the stigma associated with it.ii Because a majority of the cases affect those of productive, working age, it creates a huge economic loss for Indonesia and forces individuals to loose wages and fall further into poverty. WHO estimates that a death from TB results in an average of 12.8 years of productive life years lost with a projected cost of $11,490 per person. This report also indicates that the average costs from morbidity from TB ranges from $149 to $898 per year for patients who continued to be undiagnosed. In addition, because a huge majority of the cases are afflict the poor and poorly educated, it decreases Indonesia’s Human Development Index rating.v The social consequences of TB to sufferers, families and society are also significant. In Indonesia, people diagnosed with TB feel ashamed because of the stigma associated with the disease. This stigma causes many affected people to be isolated and discriminated against by their families and communities, which creates another barrier to providing sufficient care and preventing further spread of infections. The disproportionate effect of TB deaths on women has an incalculable effect on the rest of the family, especially the children. This problem is a contributing factor for the increasingly problematic social situation as well as the growth in the number of street children.viii Policy Action Steps: Although Indonesia currently faces an economic burden, we need to control TB now to evade a more challenging and costly problem in the future. Despite Indonesia’s high burden of disease, DOTS has had a tremendous impact on Indonesia’s strategy for TB control and is very cost-effective; active TB patients can be treated for as little as $15. The program was first introduced in 1992 in Sulawesi and reached 100% by 2007. Moreover, Indonesia has surpassed the WHO’s target of 85% at 91% for DOTS treatment success, and our case detection rate has more than doubled over the past six years to 68%.i Although DOTS has vastly improved the TB problem in Indonesia, the program needs to be effectively implemented in the eastern regions of Indonesia and Sumatra and needs to focus on fighting MDR TB and the TB/HIV co-infection problem. Our current goals are to improve the management of second-line drugs and drug resistance testing, improve the administration and 2 adherence of the TB drug regimen through supervised drug intake and an uninterrupted supply of TB drugs, expand the quality of DOTS to Sumatra and the eastern regions of Indonesia, improve case finding, and strengthen local government commitment and human resources.iii Furthermore, we need to concentrate our efforts on strengthening diagnostic services operations researchi, integrating HIV and TB prevention, treatment, and support services in hospital settings and areas in which ARVs are currently being delivered, improving the availability of HIV testing and counseling services, and expanding peer to peer consultation to spread information about TB to remote communities and to reduce the stigma associated with this disease.vii This multidisciplinary approach will better help to control TB and at the same time HIV in Indonesia. USAID.(2009). “Infectious Diseases: Indonesia.” http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/id/ ituberculosis/countries/asia/indonesia_profile.html ii Skolnik, Richard.(2008). Essentials of Global Health. Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Massachusetts. iii de Jongh, Rene, MD. (2010). “Tuberculosis.” Expat Website Association. Jakarta, Indonesia. http://www.expat.or.id/medical/tuberculosis.html iv Marzuki, Sangkot, RHH Nelwan, and Tom Ottenhof. “Tuberculosis in Indonesia: Protection, Care, and Cure.” http://www.knaw.nl/indonesia/pdf/Tuberculosis.pdf v WHO: Regional Office for South-East Asia. (2010). “Communicable Diseases: Country Profiles-Indonesia.” http://www.searo.who.int/en/Section10/Section2097/Section2100_14798.htm vi WHO. Country Office for Indonesia. (2010). “WHO Indonesia: Tuberculosis.” http://www.ino.searo.who.int/en/Section4/Section21.htm vii IRIN. (2010). “Indonesia: Fighting TB stigma.” http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=88754 viii Hadisumarto, Djunaedi M.D., “The socioeconomic impacts of tuberculosis in Indonesia.” Stop TB. http://www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/events/meetings/amsterdam_conference/indonesia.pdf i 3