File - Portfolio: Higher Education Student Affairs

advertisement

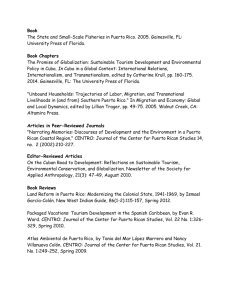

Running Head: DECULTURALIZATION 1 Damaris Sargent EDLD 509 Educational Leadership in a Pluralistic Society Book Review Inna Gorlova November 08, 2011 DECULTURALIZATION 2 Joel Spring’s Deculturalization and the Struggle for Equality examines the educational policies in the United States that have resulted in intentional patterns of oppression by Protestant, European Americans against racial and ethnic groups. The historical context of the European American oppressor is helpful in understanding how the dominant group has manipulated minority groups through deculturalization techniques, applied to erase their identities and assimilate them into society at a level at which they can be exploited. Techniques include isolation from family, replacement of language, denial of education, inclusion of dominant group world view, and provision of inferior teachers and poor facilities. Relationships between educational policy, instances of racism, and patterns of oppression are explored in the paragraphs below. A section will also compare my educational experiences to those presented by Spring. In the years before and after the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, Native Americans have experienced cultural genocide, deculturalization, and denial of education (Spring, 2010). For European American educators, the “civilizing” of Native Americans included the installation of a work ethic; the creation of desire to accumulate property; the repression of pleasure, particularly sexual pleasure; the establishment of a nuclear family structure with the father in control; the implementation of authoritarian child-rearing practices; and conversion to Christianity (Spring, 2010, p. 14). Thomas Jefferson’s civilization program called for government agents to establish schools to teach women to spin and sew and to teach men farming and husbandry (Spring, 2010). Educational policies such as this set the stage for purchasing land and avoiding costly wars. Replacing the use of native languages with English, destroying Indian customs, and teaching allegiance to the U.S. government became major educational policies regarding Native Americans in the latter part of the 19th century. An important part of these educational policies was the boarding school, which was designed to remove children from their families at an early DECULTURALIZATION 3 age and thereby isolate them from the language and customs of their parents and tribes (Spring, 2010). The Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, became the first boarding school for Native American children in 1879, instilling individualism and self-responsibility in order to break Native Americans from a socialist lifestyle. It was not until 1974 that Native American students were granted freedom of religion and culture by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Later, in 1978, Congress granted all Native Americans religious freedom. The Native American Languages Act of 1990 committed the U.S. government to reversing its historic position, which was to erase and replace Native American culture. However, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 reverses attempts to preserve usage of minority languages (Spring, 2010). After the United States had taken Mexican and Porto Rican Territory, the U.S. government instituted deculturalization programs to ensure that these new populations would not rise up against their new government (Spring, 2010). The Naturalization Act of 1790 prevented Hispanics from getting actual citizenship through limitations placed on voting rights and segregation in public accommodations and schooling (Spring, 2010). Moreover, in many instances, U.S. farmers would rather Mexican children work longer hours than go to school. Mexican students were forced to speak English in schools. In the last half of the nineteenth century, Mexican Americans tried to escape anti-Mexican attitudes by attending Catholic schools, where linguistic diversity was respected. Puerto Rico was colonized in 1898, and U.S. educational policy attempted to replace Spanish with English as the majority language and to introduce children to the dominant culture (Spring, 2010). Examples of deculturalization methods include U.S. flag ceremonies and studies focusing on American traditions. In 1912, the Puerto Rican Teachers Association resisted the educational policies of the U.S. and defended the use of Spanish in schools. In 1951, after 50 years of struggle, Puerto Rico DECULTURALIZATION 4 became a commonwealth, and Spanish was once again used in the schools without the dogma of English only laws. Additionally, in 1968, the Bilingual Education Act was passed. It was not until 1974 that the Equal Educational Opportunities Act gave protection to the language rights of students who do not speak English natively (Spring, 2010). Presently, there are many voluntary immigrants from Latin America in the U.S. school system. These students are often faced with an assimilation policy aimed at Americanizing them. Historically, Africans have been involuntary immigrants who were brought to the U.S. to be slaves. From 1800 to 1835, education of enslaved Africans was banned. Spring notes that plantation owners were in constant fear of slave revolts and, because of the need for farm laborers, planters resisted most attempts to educate black children (Spring, 2010). Segregation resulted in racial divides, unequal school funding, and inferior facilities. Booker T. Washington established the Tuskegee Institute and negotiated for segregated schools while W.E.B. Du Bois, in 1909, formed the National Association of Colored People (NAACP), which worked for desegregation (Spring, 2010). It was not until 1954 that the Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. Much credit is given to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. for helping push for civil rights legislation of 1964, along with political equality as well as the right to vote. African Americans have made significant gains in the past 100 years; however, the pace of change has been painfully slow. The election of a part African American President is a strong indication that the U.S. has come a long way. Asian Americans, many of whom have been voluntary immigrants, include individuals from China, Philippines, Japan, Korea, and other counties. The combination of racism and economic exploitation resulted in educational policies designed to deny Asians schooling or to DECULTURALIZATION 5 provide segregated schools (Spring, 2010). In 1872 the California school code provided no public education for Asian Americans. In 1906 the San Francisco School Board created segregated schools for Chinese, Japanese, and Korean students. Finally, in 1974, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Chinese American parents in Lau v. Nichols. The decision required public schools to provide special assistance to non-English-speaking students, allowing them to learn English so that they could equally participate in the educational process (Spring, 2010). Each minority group worked for a more equitable educational system. There is still a dominant European American paradigm in place, but the U.S. may see more multicultural paradigms emerge as the percentage of minority Americans rises in the coming decades. My early education took place in an environment of mostly white teachers and students. The furthest my exposure to different cultures went was going to school and growing up with my Catholic neighbors. My elementary school and middle school were 100 percent white and my high school had few Hispanic students. For me, this was normal; I knew little of other cultures. When I reflect on my American History and Social Studies classes, I recall a sanitized story presented with many anecdotes about honorable white men. Although I finished my high school education in 1996, I remember that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or Civil Rights were hardly ever mentioned. Moreover, a great deal of social upheaval was obviously occurring; however, the only topic related to the turmoil of the era that made it to my awareness was the war in Viet Nam. After high school I attended a small private college in Muskegon, Michigan. I was acquainted with very few people from different countries. All of my professors were apparently European Americans and I continued to study mostly dominant culture stories. Now that I am a DECULTURALIZATION 6 graduate student at EMU, I am able to meet a lot of different people from diverse countries and converse with them to learn about their cultures. From Spring’s book, I learned about the many minority groups that were mistreated and intentionally harmed on both personal and cultural levels. Furthermore, I was ignorant about the attempts at deculturalization of Puerto Ricans. Additionally, I knew little about the detailed history of denying education to Asian and Mexican Americans. While I knew about reeducation and denial of education of Native and African Americans, I did not know the extent to which political, economic, and social forces combined to prevent these groups from experiencing their historical culture or from participating in the dominant, European American culture. In conclusion, European Americans have quashed cultures in the United States through their control of education to support vested interests, suffocating Native American culture and hollowing multiple other cultures through various injustices. Persistent attempts to correct the status quo by the NAACP, Martin Luther King Jr., and several other organizations and individuals have moved the U.S. government to redress some inequities in the educational system. Mexican Americans were also placed in English-only schools or no school at all, and in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Puerto Rican and Asian American students both faced the threats of deculturalization. Legislation, then, has also redressed some inequities in educational opportunities for these groups, while the No Child Left Behind Act has reduced some of these multicultural gains, which disappoints many in the teaching profession. DECULTURALIZATION 7 References Spring, J. (2010). Deculturalization and the struggle for equality: A brief history of the education of dominated cultures in the United States. (Sixth ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages.