John Harris spoke about writing the music for Mary Stuart the week

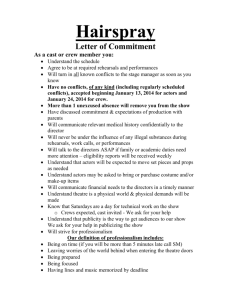

advertisement

John Harris spoke about writing the music for Mary Stuart the week the play opened. What were your starting points? The director Vicky Featherstone and I had quite early discussions in a café in Edinburgh. They were very very general at that stage and that’s quite nice – you just say what you feel about the play. There was a very obvious trap in the script . . . not a trap, but a very obvious decision that one could take, in that it could feel very Shakespearian and portentous and a bit of a period piece if you weren’t careful. You could do the men-in-tights version if you know what I mean, and I’ve never written men-in-tights music – it’s not actually something that I think I’d be capable of doing, to be honest! Working with Vicky is great because she knows that’s not what I do, and I know that’s not what she does. Her whole thing was that it should be extremely contemporary: that the themes of modern day terrorism were there and she didn’t really want to shy away from those. Also the ways that power works and the way that power and religion are intertwined were important. One of the things that we both felt very strongly was that there was both a beauty and a terror to the play the whole way through, that both coexisted almost continuously throughout. That was an incredibly important starting point for us. There’s a composer who’s a bit of an obsession of mine called Robert Carver who lived in Scotland in a similar time to Mary Stuart. He’s this extraordinary High Renaissance composer, which means he sounds like Palestrina or Lassus or any of those continental composers of the time or slightly earlier. He writes with very, very complex polyphony, which means multiple voices all singing at the one time; there are a lot of intellectual games going on with the score. It’s incredibly intelligent music. Carver’s very contemporary in some ways and I was quite keen to use a lot of his basic ideas, if not his actual music and the actual sounds of it. Of course it does sound like High Renaissance polyphony and you just can’t get away from that. If that’s the sound you want, then that’s the sound you’ll get, and I wasn’t sure that I wanted it in the play. I was keener to take ideas from the way he composes and use those within what I did. I can’t see the end from the beginning when I do shows. I am not really one of those composers that has a toolkit of sounds or instruments or even styles that they bring along: I tend to take each job as it comes. I suppose people listening may see it differently, but for me starting a new job is always like starting again from a new perspective. Did the other production elements inspire you? They always do, they always do. I almost can’t start to think what the music’s like until I’ve seen a set box and until I’ve heard the actors read the script through. I don’t know what it is about the set design that I picked up on, but in the discussions with copyright © 2006 National Theatre of Scotland Vicky we talked a lot about the fact that it’s very modernist and extremely brutal in some ways: three enormous walls, a vast column and a trap door and that’s it. I quite like those kinds of set, those very abstract sets, because they are a fairly blank canvas on which you can paint things. The set, the music, the light and the actors must all fit together and to some extent they must also not duplicate. For me, if you create something that basically duplicates what someone else is doing, if for instance you create a “musicscape”, for want of a better word, that simply describes the world that the set is describing, then what’s the point? And the same is true if you just follow and ape what the actors are doing. It’s something that we found in rehearsals, that if you underscore a scene you say, This is what the scene is about, or This is the mood of the scene, it doesn’t give the actors any space at all. So actually what we ended up doing was cutting out a lot of the atmospheres for the simple reason that it didn’t let the actors do their job. So for me it’s really important that music finds a dimension that nothing else can do: it describes something; it brings something to the production that another resource can’t. You talked about the two themes of beauty and terror as being part of your initial discussions. Did you work from those ideas? Yes. I think that’s one of the reasons why I’m quite attracted to this play, because – compositionally speaking - I’m interested in those two things. You either enhance the beauty by setting it against its opposite or you enhance the terror by supplying its opposite. Fear and pleasure; they’re quite primal, they’re quite primitive, they go straight to our gut instincts. There’s nothing more basic than that. When I delivered the sound I said to Vicky, “Look, I’m really sorry about this, but I think that for this I’ve made some of the most horrendous noises I’ve ever made for a show, and also some of the most beautiful – and I think I’d really like to try and retain both”. What was your process as a composer? I really like it when I don’t know what I’m going to do. I try to find materials to start with, but I’m not totally sure what’s going to happen. I knew that I wanted to have resonances of15th Century music in there, but I didn’t want them to be explicit, and I knew I wanted to play with this idea of updating the ancient, so I found an extremely out of tune harpsichord and went and played some chords on it. I also went out and found a countertenor, which is also very much of the period. And I went and recorded an Elizabethan trumpet (a cornetto) which I never used in the end. I also recorded a bass clarinet as I knew I wanted something rumbly going on, a cor anglais because it has a kind of oboeish noise, and the organ as well. I went and hunted down these starting materials and began working with them. I quite like the idea that a sculptor could go and find a few lumps of wood, and whatever the lump of wood is, it’s going to tell the sculptor how the sculpture is going to be. It’s much the same with this. So I went back to Carver and I took two or three things from him: particularly the theme from his ‘Missa L’Homme Armé’, which is based on a quite well known mediaeval tune, and I took it pretty much as a straight quote. Carver does odd things, like he writes in two keys simultaneously – another very contemporary idea. He is copyright © 2006 National Theatre of Scotland endlessly shifting between major and minor modes and if you look at the score for Mary Stuart it also does that. It’s primitive, but it works – facetiously speaking major equals happy, minor equals sad, like beauty and terror, those two things coming together to make something new by constantly shifting in juxtaposition to each other. How did you find out what it was that the play needed in terms of music? Crikey that’s a really hard question! This sounds like a really strange answer, but in working out what each cue is going to be you just hear the noises in your head. It’s almost impossible to intellectualise it. You can guess where the places are going to be, for instance there are dramatic moments where you need to stick something in – scene changes are obvious places although not all of them. Knowing where is not so hard, what is much more a question of gut instinct and a sort of vague idea in your head. In terms of being in rehearsals, were there any moments that really inspired you? It’s absolutely critical to sit there for quite a long time. Just the way that actors are speaking makes an enormous difference to how you think about the music. To hear the first read-through and to hear the way they work together with their voices and to see how they move. Can you say more about the importance of hearing actors’ voices? Yeah. I don’t know what it is about the actors’ voices, but the play isn’t there until they speak. The music and the voices have to work together, even the speed at which they talk can be incredibly important. For example, they can really give you a feel for the pace of a cue. Simple technical things like, if you do want to write something that goes under actors speaking, you don’t write the music at the frequency at which they’re talking otherwise you can’t hear them! But there is more to it than that. It really informs the pacing of the music, even the essential nature of it. You can look at all of the sounds – the show music and the actors’ voices, even their footsteps and other physical noises – as being part of the whole, and they must function well together. Were there any really big challenges in this and how did you overcome them? I actually have to say I find all writing music for plays pretty challenging and they all have their individual problems. Because I don’t bring a stock set of stuff, every single play is equally hellish, it’s this whole thing that I can’t see the end of and I have no idea what it’s going to be like until it’s done. I think one of the challenges was that we thought we were going to need a lot of underscore, and underscore is exceptionally tricky. It’s the difference between film and theatre, because theatre is a live performance, what you do influences what the actors do. So if you’re going to write underscore then you’re writing a duet with the copyright © 2006 National Theatre of Scotland actors. It’s not like film, it’s quite the reverse – in film the performances are fixed by the time you’ve got to seeing the final cut and it’s a question of going with that fixed object. That’s not the case in theatre because the performance someone gives two weeks before the show opens is often fantastically different from the performance they give on the opening night and the performance they give on the fourth night is different from the second night. Those things are very important because the whole point about theatre is that it’s live. That’s why a fixed, non-living, non-breathing underscore is such a difficult thing to make work well. John Harris was interviewed by Naomi Ludlam. copyright © 2006 National Theatre of Scotland