doc

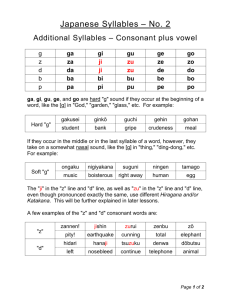

advertisement

Consonant harmony and coronality John R. Rennison 1. Consonant harmony and vowel harmony Please do not expect this article to make sense as a text. It simply shows you some typical formatting. As early as 1980, Jean-Roger Vergnaud summarised the formal properties of harmony systems in natural languages. In the past 20 years, the autosegmental treatment of vowel harmony has been refined and adapted in various ways, but has remained one of the core phenomena for which phonological theory has a standard account. In language L, autosegments of type T are interpreted non-locally at positions of type V within a domain D. I would like to extend this characterisation of VH to consonant harmony, along the lines of (1), with the parametric restrictions given in (2). (1) A general formulation of harmony processes: In language L, autosegments of type T are interpreted non-locally at positions of type p within a domain D. where p = V or C, and T = I, U, ATR, A, L, H (2) Parameters for harmony processes: p can be restricted to V or C, or to V or C realising (one/some/all of) the element(s) E. T can be restricted to one or more elements not contained in E. Clearly, the aptness of these formulation depend crucially on the properties of the phonological theory to which they relate. Under the general approach of Government Phonology (GP) laid out by Kaye, Lowenstamm & Vergnaud (1985, 1989), I assume the variety set forth in Rennison & Neubarth (in press), and the type of autosegmental tiers proposed in Rennison (1987, 1990). 2 John R. Rennison (3) Chichewa vowel harmony (from Rennison, 1987) a. A-tier A A | | I,U-tier I I I I | | | | skeleton C V C V C + V C V C p e l e k e z + e dw+ b. A-tier A A | | I,U-tier I I | | skeleton C V C V C + p e l e k + I | V C V e l + a A I | V C V C e z + a n + I | V C V i ts + a In (3) we see the tier configuration of Chichewa, a Bantu language. The elements I and U share a tier, and the element A has a tier of its own. The VH process shown in (3a,b) is what has been called parasitic harmony. It could be formulated as in (4). (4) Chichewa vowel harmony rule (first formulation) An element on the A-tier that is associated with a nucleus that is associated with an element on the I,U-tier spreads rightward to a nucleus that is associated with an element on the I,U-tier. I hope that you will agree that the formulation in (4) is rather clumsy. Moreover, I would like to claim that it misses the point, because the I,U-tier is mentioned twice. This seems to imply that one occurrence of “I,U-tier” could perhaps be replaced with the name of a different tier – and I think that that is not the case. On the contrary, it is quite essential that the I,U-tier be present to provide a vehicle for A-harmony to use. I therefore represent parasitic harmony of this kind with associations from element to element rather than from element to skeleton. My reformulation of the Chichewa vowel harmony rule is given in (5). (5) Chichewa vowel harmony rule (final formulation) An element on the A-tier sees the I,U tier and spreads rightward along it. Consonant harmony and coronality 3 Of course, this type of representation means that the “no-crossings constraint” must be reformulated. The harmonising A-element in (3b) must be sensitive to whether or not it is trying to attach to an I or U element that is realised further right than the position where the second A element in (3b) is realised. 2. The R element 2.1. Why we need an R element The second ingredient of my analysis of consonant harmony involves the representation of coronal consonants. There is a school of thought within GP which equates the R element with the A element. (6) SOAS 1992 revised elements: A = R (cf. e.g. Williams, 1998) The merger of the R element with the A element neatly accounts for the behaviour of vowels preceding positions where phonetic [r] is lost in English and German. So not much is gained by getting rid of the coronal element. The problem with the R element is that it is not found in vowels, and is therefore a prime target for reduction. However, I propose that we make a virtue out of this vice and take the coronal element to be something special. (7) Some important properties of the R element: a. It ensures that segment inventories of languages contain more consonants than vowels, ceteris paribus. b. When present, it clearly identifies a consonantal position. It is the property in (7b) that provides the raison d’être of consonant harmony. If a harmony process is parasitic on the R element, then it will always a) affect consonants but skip over intervening vowels, and b) add some element other than R itself to the representation of the target segment. 4 John R. Rennison 2.2. Combinations of R, I and U The available elements in the Rennison & Neubarth (in press) model of GP is given in Table 1 below). Table 1 The phonological elements of Rennison & Neubarth (in press). (ME = melodic expression) element F I U R H L position C V C V C V C V C V C V as head of ME stop “A” (non-high)1 i-glide “I” (front) u-glide “U” (rounded) liquid n/a fricative high tone nasal nasal / low tone as operator in ME fricative ATR palatal front labial, “dark” rounded coronal n/a aspiration high tone voiced nasal / low tone The elemental composition of some consonants relevant to CH are given in Table 2 below. Table 2 Some representations of consonant types: fricatives a. Polish type plain alveolar palatalised alveolar plain post-alveolar palatalised post-alveolar b. elements R R,I R,U R,IU consonant [s] [sj] [ʃ] [ɕ] full ME of example (F,FR) (F,FRI) (F,FRU) (F,FRIU) elements R R,U R,IU consonant [s] [θ] [ʃ] full ME of example (F,FR) (F,FRU) (F,FRIU) English type plain alveolar plain post-alveolar palatalised post-alveolar Consonant harmony and coronality 5 3. Consonant harmony 3.1. Zayse Now let us look at a typical case of CH: the sibilant harmony of Zayse, an Omotic language documented by Hayward (1986). I have chosen this process because it a particularly simple case of root-controlled harmony. Some relevant data are given in Table 3 below. Table 3 Data on sibilant harmony in Zayse (Omotic) – from Hayward (1986) stem a. merb. na ̤ʃʒa ̤ʃen- causative mersis na ̤ʃiʃ ʒa ̤ʃiʃ ʃenʃiʃ gloss forbid love throw buy Words of type a. are the most common in Zayse, and here what I assume to be the lexical form of the suffix, namely /sis/ emerges without modification. But if the word stem contains a post-alveolar fricative, in any position and whether voiced or voiceless, it causes the s’s of the causative suffix to assimilate and become post-alveolar too. My analysis of this assimilation process is given in (8). (8) Representation of “sibilant harmony” in Zayse [SSiS ‘cause to buy’ as U-harmony parasitic on R I,U-tier U | R-tier R R R R | | | | skeleton C V C V C V C V ʃ e n ʃ i ʃ Unfortunately, I do not know enough about Zayse to say whether the language has a segment to which this /n/ could change – although I would doubt it. However, if this were the case, the analysis could still be maintained with the addition of visibility of another tier containing elements that are associated to an /s/ – for example the F-tier or the tonal tier. 6 John R. Rennison 3.2. Other cases I think it should be fairly clear how other cases of CH will be analysed under this approach. The crucial point is that the R-tier becomes visible to an element on another tier. This means that the target of CH will usually be a plain coronal (although actually, there is no reason why it should not be more complex), but crucially, it means that some element will be added to the melody of the target segment. So, for example, palatal harmony, labial harmony and laryngeal harmony can be adequately handled in this way. In (9) I have given the typological consequences of this treatment of CH. (9) Typology of consonant harmony a. The target consonant always contains an R element b. The harmonising feature can be I (palatality) U (labiality) H (aspiration) N (nasality) F (spirantisation) or a combination of these c. No vowel will block consonant harmony 4. Conclusion The main implication of this analysis is that CH is not structure sensitive. In other words, in GP terms, we do not need to assume that there is an Onset projection – which would be a catastrophe anyway, since it would predict that not only coronal consonants harmonise, but also labials, palatals and velars. (10) There is no Onset Projection. Notes 7 Notes (Your endnotes should automatically appear below this paragraph. Feel free to edit them, but do not delete this paragraph or try to remove the line which follows it!) 1 In this paper, for better comprehensibility, I will sometimes refer to the older A element rather than the F-head. 8 John R. Rennison (Your endnotes should automatically appear on the previous page. Please do not change or delete this paragraph. It will be removed by the editors.) Bibliography Hayward, Richard J. 1986 Remarks on Omotic Sibilants. In Papers from the International Symposium on Cushitic and Omotic Languages, Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst and Fritz Serzisko (eds.), 263-299.). Hamburg: Buske. Kaye, Jonathan D., Jean Lowenstamm, and Jean-Roger Vergnaud 1985 The internal structure of phonological elements: a theory of charm and government. Phonology Yearbook 2: 305-328. 1989 Konstituentenstruktur und Rektion in der Phonologie. In Phonologie, Martin Prinzhorn (ed.), 31-75. (Linguistische Berichte Sonderheft 2/1989.). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag. Rennison, John R. 1987 Vowel harmony and tridirectional vowel features. Folia Linguistica XXI: 337-354. 1990 On the elements of phonological representations: the evidence from vowel systems and vowel processes. Folia Linguistica XXIV: 175-244. Rennison, John R., and Friedrich Neubarth in press An x-bar theory of phonology. Ms. www.univie.ac.at/linguistics/gp/papers/neubarth_rennison_xbar.p df. Williams, Geoffrey 1998 The Phonological Basis of Speech Recognition. Dept. of Linguistics. Ph.D. dissertation, SOAS, University of London.