Basics of Poetry

advertisement

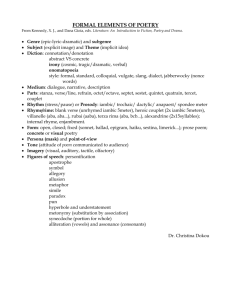

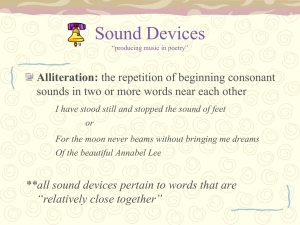

Basics of Poetry 1. RHYTHM: In speech, the natural rise and fall of language. 2. METER: The recurrence in poetry of a rhythmic sound pattern. When we speak of verse, we are speaking of meter and rhythm. 3. FOOT: The basic metrical unit, consisting of one accented and one or more unaccented syllables. 4. BASIC KINDS OF FEET: (Stressed sylables printed in boldface) a . Iambic ex.: to day b. Trochaic ex.: daily c. Anapestic ex.: in ter vene d. Dactylic ex.: yes ter day e. Spondaic ex: foot ball f. Monsyllabic ex: true Terms such as iambic are adjectives modifying a noun (iambic pentameter); the corresponding nouns that name the feet are respectively iamb, trochee, anapest, dactyl, spondee, and monosyllable, and left and right. (Just keeping you sharp) a. Monometer: one foot, 2-3 syllables b. Dimeter: two feet, 4-6 syllables c. Trimeter: three feet, 6-9 syllables d. Tetrameter: four feet, 8-12 syllables e. Pentameter: five feet, 10-15 syllables f. Hexameter: six feet, 12-18 syllables g. Heptameter seven feet 14-21 syllables h. Octameter: eight feet, 16-24 syllables 5. LINE: The secondary unit of metrical measurement, which measures the number of syllables in a line, but expressed as feet. Are you paying attention? 6. RHYME: The identity of terminal sound in accented syllables, based on vowels and succeeding consonants in the rhyming words. Many distinctive types of rhyme exist, but the most important distinction is between internal rhyme, occuring within single or successive lines, and end-stopped rhyme, occuring at the end of successive lines. 7. OTHER MUSICAL EFFECTS INCLUDE: a: Assonance, the repetition of vowel sounds. b: Alliteration, the repitition of consonantal sounds. c: Dissonance, the intentional harsh and unmusical combination of sounds. d: Consonance, where the final consonants in stressed syllables agree, but the preceding vowels do not, as in ran/run. 8. RIGID FORMS: Poetry in a format that requires the language to adhere to specific meter, rhythm, and rhyme. Other terms of importance include quatrain (four lines) , octave (eight lines), sestet (six lines), triplet (three lines) and couplet (two rhyming lines). a: Shakespearean or Elizabethan Sonnet 14-line regular form. 1- Three quatrains -(or an octave and a quatrain) followed by a couplet. 2- The first octaves/quatrain pose a situation, which is amplified or commented on by the final quatrain and/or the couplet. The concluding couplet is usually meant to have great rhetorical force. 3 - Iambic pentameter or hexameter (10- 12 syllables) in rigid rhyme schemes as follows: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG b: Petrarchan Sonnet: 14-line regular form. 1- An octave or two quatrains followed by a sestet or two triplets. 2- The first octaves/quatrain pose a situation, which is amplified or commented on by the final quatrain. 3- Iambic pentameter or hexameter (10-12 syllables) in rigid rhyme schemes as follows: ABBA ABBA CDCDCD ABBA ABBA CDE CDE ABBAACCACDCDCD c: Villanelle: originally French, tremendously difficult a 19-line form. I- There are six stanzas, and the last is a quatrain. All the others are triplets. 2- Only two rhymes are allowed. 3- The first and third lines of the first stanza must be alternately repeated as the final succeeding four stanzas, and the final quatrain must compose the last two lines. 4- Usually in iambic pentameter, rhyme scheme as- follows: ABA ABA ABA ABA ABA ABAA 9. BLANK VERSE: Iambic pentameter that does not rhyme. Shakespeare often wrote in blank verse, Milton almost always when he wrote in English. From MacBeth: Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow Creeps in its petty pace from day to day, And all our yesterdays have lighted fools The way to dusty death ... 10. FREE VERSE: The absence of form, but do not be deceived:. the grammatical enjambment of phrase, and the musical selection of sound, among many other factors, continue to mark poetry as much that it has always been, a compression and concentration of both language and experience, meant to be heard aloud, that places (again) both language and experience under pressure. I love Fun-size Snickers. A short list of poetic figures Remember, they're almost all, almost always just different flavors of metaphor. Any metaphor will have a tenor--something that the writer is trying to describe in some way-and a vehicle-the essentially unlike thing that is being used to describe it Remember-metaphor, as we have discussed, is when something literal means something else besides the literal, or (more conventionally) two unlike things are compared in order to better describe the less familiar. Remember? That is, everything means something else, other than itself alone. This is usually also true in real life, whatever that may be. Here are the different types of figures, and examples of each: a: Metonymy: A significant detail or aspect of an object or experience is used to describe the thing entirely. Metonymy is closely r6lated to synecdoche, a metaphor in which a part of something is used to represent the whole, as in "He lost face" for the loss of an individual's social standing and self-esteem-the face is given as the entire person. A metonymy from the book of Genesis: In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread. b: Allusion: The poet refers to a figure in literature or mythology or the larger culture. From A.E. Houseman's "Terence, This Is Stupid Stuff': And malt does more than Milton can To justify God' s ways to man. c: Simile: A metaphor constructed using "like" or "as". From Milton's Paradise Lost: A dungeon horrible, on all sides round As one great furnace flamed ... d: Imagery: The evocation of sensory experience-usually primarily visual-in the mind of the reader. From Hayden's "Those Winter Sundays": Sundays too my father got up early And put his clothes on in the blueblack cold ... e: Hyperbole: The use of overstatement in the service of truth. From MacBeth: No; this my hand will rather The multitudinous seas incarnadine, Making the green one red ... f. Metalepsis: A complex figure, sometimes also called a transumption, where one trope or figure is added to another, and literal meanings compressed together at such extremity that a whole raft of figures collapse into the single allusion. The entire figure has that function-no single portion can be separated. This first is from Marlowe's Doctor Faustus: Was this the face that launched a thousand ships And burnt the topless towers of Ilium? And from Yeats' "Leda and the Swan'.): A shudder in the loins engenders there The broken wall, the burning roof and tower And Agamemnon dead ... g: Irony: Situational, verbal, or cosmic, it always boils down to the eternal difference between appearance and reality. Examples abound. This one is from Julius Caeser: Brutus is an honorable man ... And this one from the book of Job: No doubt but ye are the people, and wisdom shall die with you ... And this one from T. S. Eliot's The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock: It is impossible to say just what I mean… A few relatively well-known metrical examples English seems best suited to iambs and trochees, and its natural rhythms work best (it seems) with iambic pentameter. Iambic hexameter, or the Alexandrine, has been used extensively in the past, but Alexander Pope (who is quoted below in our example of an iambic hexameter line) pretty well put an end to it. Anapestic tetrameter is seldom used. It sounds so jingly. Dactylic tetrameter is used so very seldom that the example given here is made up. I was unable to find, in time for class, any poem using it. The examples: a: Iambic tetrameter: Whose woods / these are/I think/ I know. b: Iambic pentameter: To sing / of wars / of cap/ tains and/ of kings. c: Trochaic pentameter: You and / I will / nev er/ read that / vol ume. d: Iambic hexameter, sometimes called the Alexandrine line: That like / a wound / ed snake / drags its / slow length/ a long. e: Anapestic tetrameter: 'Twas the night / before Christ / mas and all / through the house f. Dactylic tetrameter: Hig gle dy / pig gle dy /Al fred Lord / Ten ny son Explication As a final cautionary note, remember how you do an explication. There are steps that you can take to prepare that will simplify things for you once you start writing. Once you start writing-given that you have prepared-the ideas are likely to come to you more easily than you think. Consider that you writing may just be a more systematic way of thinking. Here, again, are the things you can do to prepare: a: Read the poem straight through once; mark all words that you don't know. b: Look up the words you don't know in a good dictionary. c: Read any footnotes. If there are allusions you still haven't gotten, check another edition of the poem for additional footnotes. d: Once you have the meanings of all words, and the information behind any allusions, sit down and paraphrase the poem from beginning to end. This will give you the literal level at the very least. e:. Identify all of the key metaphors, and then identify the tenor and vehicle of each metaphor. f. Identify the patterns that have emerged. Begin with any repeated words, allusions, or categories of word and allusion. Some sense of meaning should begin to take shape early in this process, and sharpen as you go. I love cheese and beans ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ What's the title of the poem? Who is the poet? What is described in the poem? Who is the speaker (may not be the poet)? What's the tone? Give two examples of stylistic devices used in the poem. The best line(s)-the most beautiful, or impressive or vivid, etc. Give one example of the unusual choice of words. Explain why. What emotions are evoked? Use one word to describe the feeling. I actually like steak and salmon, more. Homework: Interpret two poems. They can be any two poems you want. We will take a quiz over this material. Or not. Enjoy!