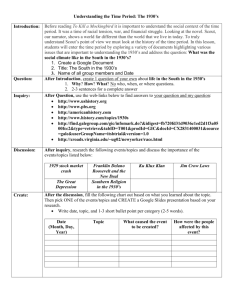

1930s Lessons: Brother, Can You Spare a Stock? February 14

advertisement

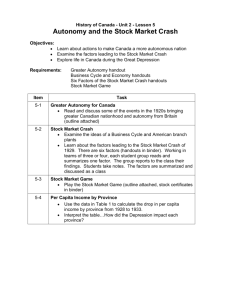

1930s Lessons: Brother, Can You Spare a Stock? February 14, 2009 By JASON ZWEIG In the worst of times, which are the best of stocks? So many readers have emailed me to warn that we are going into another Great Depression that I decided to find out which companies and sectors did best after the Crash of 1929. With the Standard & Poor's 500-stock index down 39% last year and another 8.5% this year, it can't hurt to learn what separated the winners from the losers back then. The good news is that some stocks and industries did indeed do much better than average. The bad news is that the average was ghastly, and even the best stocks had three rotten years in a row. With the help of the Center for Research in Security Prices, or CRSP, at the University of Chicago's Booth School of Business, I sought to answer this question: If you had invested on Jan. 1, 1930, after the crash already had destroyed a third of the stock market's value, where would you have gotten the greatest gains? The short answer: In 1930, 1931 and 1932, nowhere. There was no real refuge in the storm; even Benjamin Graham, the great value investor, lost 60% over those three years. According to CRSP, only one industry had positive returns from 1930 through 1932: logging. The two stocks in that tiny sector, Diamond Match and Mengel Co., whittled out a cumulative gain of 40% for the three-year period. Diamond turned timber into matchsticks; Mengel made trees into packing materials, primarily for daily necessities like tobacco and soap. To find a major sector with significantly positive returns, CRSP needed to stretch our measurement period into a fourth year, 1933, when the market finally rebounded partway from its earlier losses by rising a record 54%. Even then, out of 120 industries, only 13 managed to generate gains from 1930 through 1933. The only clear winner: cheap vices. Among the sectors with positive returns were cigarettes, cigars and tobacco, sugar and confectionery products, and fats and oils, which each gained between 1.6% and 7.5% annually. Those gains were better than they look, because deflation raised their purchasing power by an annual average of more than 6% over this period. It seems there was good money to be made investing in guilty pleasures that people could afford even in the hardest of times: sweets, smokes and fried food. learn that we could have earned a 5.9% annualized return by investing in leather tanning and finishing stocks, for example. And the agriculture-and-commodity-based economy of the 1920s and 1930s was quite different from today's world. Barrie Wigmore is a retired investment banker at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. whose book "The Crash and Its Aftermath" is an indispensable guide to the stock market during the Depression. He says: "The truth is, we're really in no man's land. We've never been here before. It's much more important to focus on the variables that we really know today without cluttering your mind up with comparisons to the Depression." What we do know, Mr. Wigmore says, is that consumers and corporations alike will be compelled to deleverage in the years to come. He sees three obvious opportunities. First would be the shares of great brand-name companies with manageable levels of debt, like Amazon.com, Google, Nikeand United Parcel Service, but only when they are at least as cheap as they were last fall. Second, you might consider the stocks of firms that enable consumers to indulge in cheap vices. Avoid tobacco companies, which often combine huge legal liabilities with too much leverage, and brewers and distillers, which also tend to carry too much debt. But companies like Costco Wholesale, where consumers can buy snacks and candy by the crate, and PepsiCo, which spews out soda pop and corn chips, might fit the bill. Of course, some of the industries in the CRSP sample scarcely exist today. It doesn't do us much good to What if, like me, you keep most of your stock money in index funds? Mr. Wigmore has been diversifying into intermediate-term, investment-grade corporate bonds, which still offer attractive yields relative to Treasury securities. Corporate bonds returned 6.7% a year from 1930 through 1933, a return effectively doubled by deflation over the same period. Even if we dodge another Depression, today's yields on corporate bonds should make them a deal.