Chapter Three: Word Classes

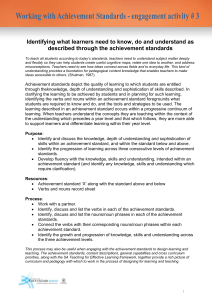

advertisement

Lesson Plans 6-8

(Week 6-8)

Chapter Three: Word Classes

1. Learning Objectives

Upon completing this chapter, students are expected to be able to:

1.1 Identify word classes

1.2 Identify open class and closed class words

1.3 State the use of certain words in sentences

1.4 Use appropriate words in sentences

1.5 Understand the different functions of words

1.6 Identify nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, and function words

2. Topics of Content

2.1 What is a word?

2.2 What is word class?

2.3 Criteria for word classes

2.4 Open and closed word classes

3. Teaching and Learning Method

3.1 Lectures

3.2 Brainstorming

3.3 Discussions

3.4 Assignments

3.5 Presentations

3.6 Identification of word classes

4. Teaching Materials

4.1 Main textbook

4.2 Supplementary materials

4.3 Transparencies

4.4 Charts

4.5 Worksheet

4.6 English Dictionaries

4.7 Authentic texts from books, newspapers, etc.

5. Measurement and Evaluation

Students will be evaluated on:

5.1 Exercises in the book

5.2 Participation in discussions

5.3 Completion of assignments

5.4 Observation the of a attention and participation of the students in class

5.5 Observation the students’ interest in group work.

5.6 Observation the students’ questions and answers on the lectures given in

class.

Chapter Three

Word Classes

What is word?

At first glance the most basic unit of linguistic structure appears to be the word.

The word, though, is far from the fundamental element of study in linguistics; it is already

the result of a complex set of more primitive parts. The study of morphology concerns

the construction of words from more basic components corresponding roughly to units

of meaning. There are two basic ways that new words are formed, traditionally classified

as inflectional forms and derivational forms. Inflectional forms use a root form of a word

and typically add a suffix so that the word appears in the appropriate form for the

sentence. Verbs are the best examples of this in English. Each verb has a basic form

that then is typically changed depending on the subject and the tense of the sentence.

For example, the verb sigh will take suffixes such as -s, -ing, and -ed to create the verb

forms sighs, sighing, and sighed, respectively. These new words are all verbs and share

the same basic meaning. Derivational morphology involves the derivation of new words

from other forms. The new words may be in completely different categories from their

subparts. For example, the noun friend is made into the adjective friendly by adding the

suffix - ly. A more complex derivation would allow you to derive the noun friendliness

from the adjective form. There are many interesting issues concerned with how words

are derived and how the choice of word form is affected by the syntactic structure of the

sentence that constrains it.

What is Word Classes?

Words are fundamental units in every sentence, so we will begin by looking at

these. Consider the words in the following sentence:

My brother drives a big car.

We can tell almost instinctively that brother and car are the same type of word,

and also that brother and drives are different types of words. By this we mean that

brother and car belong to the same word class. Similarly, when we recognize that

brother and drives are different types, we mean that they belong to different word

classes.

English words can be grouped together into word classes. The word classes are

called parts of speech. They are classified into open class and closed class. The open

class or major word classes consist of four classes of word: noun, adjective, adverb and

verb. The closed classes or minor word classes consist of articles, determiners,

pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, auxiliaries and interjections.

We recognize seven Major word classes:

Verb

Noun

Determiner

Adjective

Adverb

Preposition

Conjunction

be, drive, grow, sing, think

brother, car, David, house, London

a, an, my, some, the

big, foolish, happy, talented, tidy

happily, recently, soon, then, there

at, in, of, over, with

and, because, but, if, or

We may find that other grammars recognize different word classes from the ones

listed here. They may also define the boundaries between the classes in different ways.

In some grammars, for instance, pronouns are treated as a separate word class,

whereas we treat them as a subclass of nouns. A difference like this should not cause

confusion. Instead, it highlights an important principle in grammar, known as

GRADIENCE. This refers to the fact that the boundaries between the word classes are

not fixed rigidly. Many word classes share characteristics with others, and there is

considerable overlap between some of the classes. In other words, the boundaries are

"fuzzy", so different grammars categorize them differently.

For the rest of the class we explore the idea that the environment of a word can

appear in the table.

Table of Word Classes

Word Class

Noun

Examples

Interjection

The yellow dog.

The cats.

The rabbit’s collar.

Very warm

Hotter

More interesting

Longest

Most boring

Jumped

Singing

I might sleep.

Please leave!

Really loud

I happily jumped

Very happily

The yellow dog

A yellow dog

This yellow dog

My yellow dog

Dogs or cats

Scream and shout

I perspire but you sweat

He might jump, mightn’t he?

He would not jump.

I could jump and so could she.

Alas!, Dear me!

Numeral

two pens, four books

Adjective

Open class

Verb

Adverb

Determiner

Conjunction

Closed class

Auxiliary Verb

Criteria for Word Classes

We began by grouping words more or less on the basis of our instincts about

English. We somehow "feel" that brother and car belong to the same class, and that

brother and drives belong to different classes. However, in order to conduct an informed

study of grammar, we need a much more reliable and more systematic method than this

for distinguishing between word classes.

We use a combination of three criteria for determining the class of a word:

1. The meaning of the word

2. The form or ‘shape' of the word

3. The position or ‘environment' of the word in a sentence

1. Meaning

Using this criterion, we can generalize about the kind of meanings that words

convey. For example, we could group together the words brother and car, as well as

David, house, and London, on the basis that they all refer to people, places, or things. In

fact, this has traditionally been a popular approach to determining members of the class

of nouns. It has also been applied to verbs, by saying that they denote some kind of

"action", like cook, drive, eat, run, shout, walk.

This approach has certain merits, since it allows us to determine word classes

by replacing words in a sentence with words of "similar" meaning. For instance, in the

sentence My son cooks dinner every Sunday, we can replace the verb cooks with other

"action" words:

My son cooks dinner every Sunday

My son prepares dinner every Sunday

My son eats dinner every Sunday

My son misses dinner every Sunday

On the basis of this replacement test, we can conclude that all of these words

belong to the same class, that of "action" words, or verbs.

However, this approach also has some serious limitations. The definition of a

noun as a word denoting a person, place, or thing, is wholly inadequate, since it

excludes abstract nouns such as time, imagination, repetition, wisdom, and chance.

Similarly, to say that verbs are "action" words excludes a verb like be, as in

I want to be happy. What "action" does be refers to here? So although this criterion has

a certain validity when applied to some words, we need other, more stringent criteria as

well.

2. The form or 'shape' of a word

Some words can be assigned to a word class on the basis of their form or

`shape'. For example, many nouns have a characteristic -tion ending:

action, condition, contemplation, demonstration, organization, repetition

Similarly, many adjectives end in -able or -ible:

acceptable, credible, miserable, responsible, suitable, terrible

Many words also take what are called Inflection, that is, regular changes in their

form under certain conditions. For example, nouns can take a plural inflection, usually by

adding an -s at the end:

car -- cars

dinner -- dinners

book -- books

Verbs also take inflections:

walk -- walks -- walked -- walking

3. The position or `environment' of a word in a sentence

This criterion refers to where words typically occur in a sentence, and the kinds of words

which typically occur near to them. We can illustrate the use of this criterion using a

simple example.

Compare the following:

1. I cook dinner every Sunday

2. The cook is on holiday

In 1, cook is a verb, but in 2, it is a noun. We can see that it is a verb in 1

because it takes the inflections which are typical of verbs:

I cook dinner every Sunday

I cooked dinner last Sunday

I am cooking dinner today

My son cooks dinner every Sunday

And we can see that cook is a noun in 2. because it takes the plural -s inflection

The cooks are on holiday

If we really need to, we can also apply a replacement test, based on our first

criterion, replacing cook in each sentence with "similar" words:

Notice: that we can replace verbs with verbs, and nouns with nouns, but we cannot

replace verbs with nouns or nouns with verbs:

I chef dinner every Sunday

The eat is on holiday

It should be clear from this discussion that there is no one-to-one relation

between words and their classes. Cook can be a verb or a noun -- it all depends on how

the word is used. In fact, many words can belong to more than one word class. Here are

some more examples:

She looks very pale (verb)

She's very proud of her looks (noun)

He drives a fast car (adjective)

He drives very fast on the motorway (adverb)

Turn on the light (noun)

I'm trying to light the fire (verb)

I usually have a light lunch (adjective)

You will see here that each in bold print word can belong to more than one word

class. However, they only belong to one word class at a time, depending on how they

are used. So it is quite wrong to say, for example, "cook is a verb". Instead, we have to

say something like "cook is a verb in the sentence I cook dinner every Sunday, but it is a

noun in The cook is on holiday".

Of the three criteria for word classes that we have discussed here, the Internet

Grammar will emphasize the second and third - the form of words, and how they are

positioned or how they function in sentences.

Open and Closed Word Classes

Some word classes are Open, that is, new words can be added to the class as the

need arises. The class of nouns, for instance, is potentially infinite, since it is continually

being expanded as new scientific discoveries are made, new products are developed,

and new ideas are explored. In the late twentieth century, for example, developments in

computer technology have given rise to many new nouns:

Internet, web-site, URL, CD-ROM, email, newsgroup, bitmap, modem,

multimedia

New verbs have also been introduced:

download, upload, reboot, right-click, double-click

The adjective and adverb classes can also be expanded by the addition of new

words, though less prolifically.

On the other hand, we never invent new prepositions, determiners, or conjunctions.

These classes include words like of, the, and but. They are called Closed word classes

because they are made up of finite sets of words which are never expanded (though

their members may change their spelling, for example, over long periods of time). The

subclass of pronouns, within the open noun class, is also closed.

Words in an open class are known as open-class items. Words in a closed class are

known as closed-class items.

1. Open Classes

Open classes (also called content words) contain most of the words in a

language since they are readily open to new words. For example, we can form new

nouns or adjectives by adding derivations. The words in these classes carry the

principal meaning of a sentence in which they occur.

1.1 Nouns

Nouns are commonly thought of as "naming" words, and specifically as the

names of "people, places, or things". Nouns such as John, London, and computer

certainly fit this description, but the class of nouns is much broader than this. Nouns also

denote abstract and intangible concepts such as birth, happiness, evolution,

technology, management, imagination, revenge, politics, hope, cookery, sport,

literacy....

Nouns are identified through a series of formal tests. They are also classified by two

aspects of form; their inflectional and derivational morpheme. Besides this, we can

apply a functional definition of nouns, because other parts of speech also occur in

typically nominal functions. For more suitable analyses, we must consider the forms of

nouns.

Moreover, most nouns are morphologically characterized by their ability to take

typical inflexion and derivation.

Typical derivations of nouns are:

-age anchorage, coverage, postage

-ance appearance, clearance, utterance

-ation affirmation, information, transformation

-cy democracy, emergency

-dom boredom, freedom, kingdom

-ee advisee, employee, payee

-eer engineer, mountaineer, profiteer

-ence difference, existence, priesthood

-ess actress, governess, murderess

-ette cigarette, usherette, maisonnette

-er-or farmer, actor, employer

-hood childhood, parenthood, priesthood

-ing working, writing, walking

-ism idealism, organism, nationalism

-ist royalist, socialist, specialist

- ity ability, nationality, responsibility

-ment amendment, commandment, shipment

-ness goodness, bitterness, happiness

-ship friendship, relationship, membership

-tion education, vocation, fruition

Most nouns have distinctive Singular and Plural forms. The plural of a regular

noun is formed by adding -s to the singular:

Singular Plural

car

cars

dog

dogs

house houses

However, there are many irregular nouns which do not form the plural in this way:

Singular Plural

man

men

child

children

sheep

sheep

The distinction between singular and plural is known as Number Contrast.

We can recognize many nouns because they often have the, a, or an in front of them:

the car

an artist

a surprise

the egg

a review

These words are called determiners, which is the next word class we will look at.

Nouns may take an -'s ("apostrophe s") or Genitive Marker to indicate possession:

the boy's pen

a spider's web

my girlfriend's brother

John's house

If the noun already has an -s ending to mark the plural, then the genitive marker

appears only as an apostrophe after the plural form:

the boys' pens

the spiders' webs

the Browns' house

The genitive marker should not be confused with the 's form of contracted verbs,

as in Wanchai's a good boy (= Wanchai is a good boy).

Nouns often co-occur without a genitive marker between them:

rally car

table top

cheese grater

University entrance examination

We will look at these in more detail later, when we discuss noun phrases.

Most nouns can take two inflectional suffixes. One to mark number (the plural)

and one to mark case (genitive).

The plural

The plural morpheme {S 1 } can be realized in three ways:

/s/

after base ending in voiceless sounds except sibilants, e.g. ants, books,

map, roofs, lips, hats, births;

/z/

after base ending in voiced sounds except sibilants, e.g. cars, birds,

days, trees, bars, laws, zoos, boys, beds, pencils;

/z/ after bases ending in sibilants, e.g.

/s/

horses, nurses, kisses

/z/

noises, sizes, noses

/z / brushes, dishes, clashes

/tƒ/ churches, torches, witches

/dƷ/ pledges, bridges, languages

There are four exceptions to the pluralization rule above.

1) Change in the base + regular suffix, e.g.

/Ɵ/ /ð / + /z/ : baths, mouths, paths

/f/ /v/ + /z/ : halves, knives, leaves

/s/ /z/ + /z/ : houses

2) Change in the base without a suffix (= mutation)

goose

geese

foot

mouse

mice

louse

man

men

woman

tooth

teeth

3) No change ( = zero plural ), e.g.

deer

grouse

sheep

species

Chinese series

Swiss

salmon

4) End in –en plural

ox

oxen

child

children

feet

lice

women

Japanese

Portuguese

The genitive

The genitive is one of the two cases of the English noun, the other being the

common case.

In the singular the genitive morpheme { S 2 } can be realized in the following

three ways:

/s/

after bases ending in voiceless sounds except sibilants, e.g.:

ship

the ship’s crew

wife

his wife’s car

dentist

the dentist’s drill

Sam

Sam’s motorcycle

/z/ after bases ending in voiced sounds except sibilants, e.g.:

George

George’s report

brother

her brother’s book

play

the play’s title

/z/

after bases ending in sibilants, e.g.:

George

George’s properties

horse

a horse’s tail

village

the village’s population

In plural nouns, the genitive morpheme is realized in two ways:

/z/

with irregular plurals not ending in -s. e.g.:

men

men’s clothes

women

women’s lip

children

children’s books

/Ø/ in all other cases, e.g.:

student

the students’ union

girl

a girls’ school

teacher

a teachers’ club

officers

the officers’ mess

The spelling of genitive suffix in both the singular and plural is either ’s or ’ The

possibilities and the relations between spelling and pronunciation are set in the table.

Genitive

Singular

Plural

Spelling

’s

’s or ’

’

’s

’

Pronunciation

/s/, /z/, /z/

/z/, /Ø/

/Ø /

/z/

/Ø/

Examples

Ship’s; wife’s

Sam’s

girls’

men; women

students’; girls;

1.1.3. Classes of noun

Nouns can be subdivided into:

1. Common nouns: these are further subdivided into count nouns and mass

nouns:

2. Proper nouns: nouns which name specific people or places are known as

Proper Nouns.

John

Mary

London

France

Many names consist of more than one word:

John Wesley

Queen Mary

South Africa

Atlantic Ocean

Buckingham Palace

Proper nouns may also refer to times or to dates in the calendar:

January, February, Monday, Tuesday, Christmas, Thanksgiving

All other nouns are common nouns.

Since proper nouns usually refer to something or someone unique, they do not

normally take plurals. However, they may do so, especially when number is being

specifically referred to:

There are three Davids in my class

We met two Christmases ago

For the same reason, names of people and places are not normally preceded by

determiners the or a/an, though they can be in certain circumstances:

It's nothing like the America I remember

My brother is an Einstein at maths

As table shows, this classification can be based on a number of syntactic criteria.

Plural Numeral many, few Much,

Def.

Indef.

several

Little

article

article

Count

+

+

+

-

+

+

Mass

-

-

-

+

+

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Common

Proper

Proper nouns do not occur in the plural and cannot be preceded by numerals or

by quantifiers such as many, few, several, much and little. Nor can they be preceded by

the definite and indefinite articles. The subclassification of common nouns into count

nouns and mass nouns is based on the fact that count nouns are positive with respect to

five of the criteria used, whereas mass nouns are positive with respect to only two

criteria: they collocate with the quantifiers much and little as well as with the definite

article. Consider:

Criteria

Examples

Plural

count :

table - tables

mass :

music - musics

proper :

France - Frances

Numerals

count :

two tables, two pens

mass :

two musics, two despairs

proper :

two Frances

Many/few/several

count :

many tables, many pens

mass :

many musics, many despairs

proper :

many Frances

Much/little

count :

much table, much pen

mass :

much music, much despair

proper :

much France

Definite article

count :

the table, the pen

mass :

the music, the despair

proper :

the France

Indefinite article

count :

a table, a pen

mass :

a music, a despair

proper :

a France

Proper nouns normally have unique reference, that is they refer to one particular

person, country, town, etc. This semantic property explains why they occur in the

singular only and cannot be preceded by articles, numerals and quantifiers.

Occasionally, however, proper nouns lose their unique reference, in which case they are

treated as count nouns, so that they can be pluralized and be preceded by numerals,

articles and by quantifiers like, many, few and several:

1.2. Verbs

Verbs have traditionally been defined as "action" words or "doing" words. The

verb in the following sentence is rides:

Paul rides a bicycle

Here, the verb rides certainly denotes an action which Paul performs - the action of

riding a bicycle. However, there are many verbs which do not denote an action at all.

For example, in Paul seems unhappy, we cannot say that the verb seems denotes an

action. We would hardly say that Paul is performing any action when he seems unhappy.

So the notion of verbs as "action" words is somewhat limited.

We can achieve a more robust definition of verbs by looking first at their formal

features.

The Base Form

Here are some examples of verbs in sentences:

1. She travels to work by train

2. David sings in the choir

3. We walked five miles to a garage

4. I cooked a meal for the family

Notice that in 1 and 2, the verbs have an -s ending, while in 3 and 4, they have

an -ed ending. These endings are known as Inflections, and they are added to the Base

Form of the verb. In 1, for instance, the -s inflection is added to the base form travel.

Certain endings are characteristic of the base forms of verbs:

Ending

-ate

-ify

-ise/-ize

Base Form

concentrate, demonstrate, illustrate

clarify, dignify, magnify

baptize, conceptualize, realize

Past and Present Forms

When we refer to a verb in general terms, we usually cite its base form, as in "the

verb travel", "the verb sing". We then add inflections to the base form as required.

Base Form

travel

sing

walk

+

+

+

+

Inflection

1. She

to work by train

s

2. David

in the choir

s

3. We

five miles to a garage

ed

a meal for the whole

4. I

cook

+

ed

family

These inflections indicate Tense. The -s inflection indicates the Present Tense,

and the -ed inflection indicates the Past Tense.

Verb endings also indicate Person. Recall that when we looked at nouns and

pronouns, we saw that there are three persons, each with a singular and a plural form.

These are shown in the table below.

Person

Singular

Plural

we

1st Person I

you

2nd person you

3rd Person he/she/John/the dog they/the dogs

In sentence 1, She travels to work by train, we have a third person singular

pronoun she, and the present tense ending -s. However, if we replace she with a plural

pronoun, then the verb will change:

1. She travels to work by train

2. They travel to work by train

The verb travel in 2 is still in the present tense, but it has changed because the

pronoun in front of it has changed. This correspondence between the pronoun (or noun)

and the verb is called Agreement or Concord. Agreement applies only to verbs in the

present tense. In the past tense, there is no distinction between verb forms: she

travelled/they travelled.

There are three derivational suffixes that are typical of the class of verbs:

-en :

brighten, darken, lighten

-ify :

purify, clarify, simplify

-ize :

economize, individualize, scandalize

Most English verbs can add four inflectional morphemes; namely

1. Third person singular present tense

{S 3 }

2. Past tense

{D 1 }

3. Past participle

{D 2 }

4. Present participle

{ing}

The rules of present tense morpheme {S 2 } in the third person are similar for

pluralization of nouns regularly realized in three ways:

/s/

after base ending in voiceless sounds except sibilant, e.g.:

talks, stops, walks

/z/

after base ending in voiced sounds except sibilant, e.g.:

learns, snores, destroys, pays, climbs, grows

/iz/ after base ending in a sibilant:

/s/

mixes, promises

/z/

freezes, sizes

/iz/ fishes, washes

/t /

catches, touches

/d/ budges, lodges

The past tense morpheme {D 1 } and the past participle morpheme {D 2 } of

regular verbs are realized in three ways:

/t/

after bases ending in voiceless sounds

except /t/ e.g.

laughed, kissed, tripped, stopped, walked

/d/ after bases ending in voiced sounds

except /d/ or /t/ e.g.

answered, cried, learned, parted, rotted

/Іd/ after bases ending in /t/ or /d/ e.g.

listed, ended

The present participle morpheme {ing} is always realized, such as, listening,

writing, learning, speaking and playing. English has over 200 irregular verbs, and

irregular verbs form its past tense or past participle {D 2 } (or both) in other ways than

those described for regular verbs. There are four possibilities as illustrated in the table

below.

Base

burst

cost

All three forms identical cut

hit

put

set

Base + {D 1 }

burst

cost

cut

hit

put

set

Base +{D 2 }

burst

cost

cut

hit

put

set

begin

choose

do

All three forms different drink

go

speak

swim

wear

began

chose

did

drank

went

spoke

swam

wore

begun

chosen

done

drunk

gone

spoken

swum

worn

{D 1 } ={D 2 }

Bases {D 2 }

bring

find

hang

keep

lead

sit

teach

think

come

run

overrun

brought

found

hung

kept

led

sat

taught

thought

came

ran

overran

brought

found

hung

kept

led

sat

taught

thought

come

run

overrun

Class of Verb

Word class of the verb, there are two subclasses that can be distinguished:

auxiliary verbs and lexical verbs. The former makes up a closed class, the later an open

class.

These classes have four major differences between lexicon verbs and auxiliary

verbs.

a) Lexical verbs require periphrastic ‘do’ in negative sentences with and in

negative sentences with not. Auxiliary can co-occur with not and can have special

contracted negative forms.

Compare:

Sam loves dog.

- * Sam loves not dog. (the statement is ungrammatical)

- Sam does not love dogs

He can sing a song. - He cannot (can’t) sing a song.

b) Lexical verbs require periphrastic ‘do’ in yes/no questions, in WH-questions

where the WH- item is not the subject and in sentences opening with a negative

adverbial. Auxiliaries can come before the subject.

Compare:

Robert plays the violin.

- Plays Robert the violin?

(the statement is ungrammatical)

- Does Robert play the violin?

Robert can play the violin. - Can Robert play the violin?

Sam leaves tomorrow.

- When leaves Sam?

(the statement is ungrammatical)

- When does Sam leave?

Sam left yesterday

- When left Sam?

(the statement is ungrammatical)

- When did Sam leave?

Sam is leaving tomorrow.

- When is Sam leaving?

A dentist seldom visits his patients. - Seldom a dentist visits his patients.

(the statement is ungrammatical)

- Seldom does a dentist visit his

patients.

A dentist can seldom

- Seldom can a dentist visit his

visits his patients.

patients.

c) Lexical verbs cannot be used in ‘code’.

Compare:

Should I meet a manager?

You can do it and he can do it

Do your students love linguistics?

John reads and Paul reads.

-

Yes, you should meet a manager.

Yes, you should.

You can do it and so can he.

Yes, they love linguistics.

(the statement is ungrammatical)

- Yes, they do.

- John reads and so reads Paul.

(the statement is ungrammatical)

- John reads and so does Paul.

The first two examples show that, instead, of repeating the auxiliary verb

together with the lexical verb (and its complement), it is possible to repeat only the

auxiliary verb. The auxiliary in such sentences is said to be used in ‘code’. The key to

the code is provided by the preceding context. The last two examples show that lexical

verbs (and their complement ,if any) must be replaced by a form of ‘do’.

d) Lexical verbs cannot be used emphatically to express a contrast, but require

emphatic ‘do’. Auxiliaries, on the other hand, can be used emphatically.

Compare:

Your son did not see her.

- Yes, he saw her.

(the statement is ungrammatical)

- Yes, he did see her.

Your son has not seen her. - Yes, he has seen her.

1) Lexical Verbs.

Lexical verbs constitute the principal part of the verb phrase. They can be

accompanied by auxiliaries, but they can also occur in verb phrases that do not contain

any other verbal forms.

Compare:

My aunt

may move next week.

may be moving next week.

moved last week

There are two ways of classifying lexical verbs. The first is base on

complementation, the second involves the distinction between one-word and multi-word

verbs.

2) Complement Verbs and Intransitive Verbs

In the sentence structures, lexical verbs can be classified as those of verbs that

do not require a complement (intransitive verbs) and verbs that do (complement verbs).

A classification based on complementation depends on whether or not the lexical verb

in a sentence can occur on its own (i.e. without a complement) or obligatorily followed

by words that complement its meaning.

The following sentences contain intransitive verbs:

The dogs bark.

The sun is shining.

The spy had disappeared.

The class of complement verb consists of two subclasses:

Complement verbs consist of transitive complement verbs and non-transitive

complement verbs.

a. Transitive complement verbs

Some transitive complement verbs require only a direct object (DO). Others are,

in addition, followed by another complement, i.e. by an indirect object (IO), a

benefactive object (BO), and an objective attribute (OA), or a predicator complement

(PC). The four classes of transitive verbs thus distinguished are:

1. Monotrasitive verbs (DO only)

The man kicked his football.

The farmer kicked the dog.

2. Ditransitive verbs (IO + DO/BO + DO)

She gave her toy.

He called her a taxi.

3. Complex transitive verbs (DO + OA)

They find him a bore.

We found his excuse unbelievable.

4. Transitive PC verbs (DO + PC)

She reminds me of her mother.

b. Non-transitive complement verbs

Non-transitive complement verbs consist of two sub-classes: copulas (or linking

verbs), i.e. verbs that are followed by a subject attribute (SA) and verbs which are

followed by a predicator complement without an accompanying direct object:

1. Copulas (SA):

Sam is an operator.

He looks sad.

2. Non-transitive PC verbs (PC)

She remembers her brother.

This pen belongs to Steven.

Complement

verbs

Transitive

complement

verbs

Non-transitive

complement

verbs

LEXICAL

VERBS

The classification of lexical verbs is shown in the table below.

Monotransitive verbs (DO only)

Ditransitve verbs (IO + DO/BO + DO)

Complex transitive verbs (DO + OA)

Transitive PC verbs (DO + PC)

Copulas (SA)

Non-transitive PC verbs (PC only)

Intransitive verbs: no complement

1.3. Adjectives

Adjectives can be identified using a number of formal criteria. However, we may

begin by saying that they typically describe an attribute of a noun:

cold weather

large windows

violent storms

Some adjectives can be identified by their endings. Typical adjectival endings include:

-able/-ible

-al

-ful

-ic

-ive

-less

-ous

achievable, capable, illegible, remarkable

biographical, functional, internal, logical

beautiful, careful, grateful, harmful

cubic, manic, rustic, terrific

attractive, dismissive, inventive, persuasive

breathless, careless, groundless, restless

courageous, dangerous, disastrous, fabulous

However, a large number of very common adjectives cannot be identified in this

way. They do not have typical adjectival form:

bad

bright

clever

cold

common

complete

dark

deep

difficult

distant

elementary

good

great

honest

hot

main

morose

old

quiet

real

red

silent

simple

strange

wicked

wide

young

As this list shows, adjectives are formally very diverse. However, they have a

number of characteristics which we can use to identify them.

Characteristics of Adjectives

Adjectives can take a modifying word, such as very, extremely, or less, before

them:

very cold weather

extremely large windows

less violent storms

Here, the modifying word locates the adjective on a scale of comparison, at a

position higher or lower than the one indicated by the adjective alone.

This characteristic is known as GRADABILITY. Most adjectives are gradable,

though if the adjective already denotes the highest position on a scale, then it is nongradable:

my main reason for coming

The principal role in the play

my very main reason for coming

the very principal role in the play

As well as taking modifying words like very and extremely, adjectives also take

different forms to indicate their position on a scale of comparison:

big -- > bigger -- > biggest

The lowest point on the scale is known as the Absolute form, the middle point is

known as the Comparative form, and the highest point is known as the Superlative form.

Here are some more examples:

Absolute Comparative

Superlative

dark

darker

darkest

new

newer

newest

old

older

oldest

young

younger

youngest

In most cases, the comparative is formed by adding -er , and the superlative is

formed by adding -est, to the absolute form. However, a number of very common

adjectives are irregular in this respect:

Absolute

Comparative

Superlative

good

better

best

bad

worse

worst

far

farther

farthest

Some adjectives form the comparative and superlative using more and most

respectively:

Absolute

important

miserable

recent

Comparative

more important

more miserable

more recent

Superlative

most important

most miserable

most recent

Many members of the class of adjectives are identifiable on the basis of typical

derivation suffixes. The comparative and the superlative inflections characterize many

adjectives.

Some common derivational suffixes for adjectives

-able, -ible communicable, reasonable, visible, comprehensible

-al, -ial

normal, racial, editorial

-ful

beautiful, careful, cheerful, useful

-ic

atomic, historic, allergic

-ical

economical, historical, political

-ish

childish, foolish, tallish

-ive, -ative attractive, abortive, massive,

-less

endless, harmless, speechless

-like

ladylike, manlike, warlike

-ous, -ious famous, dangerous, spacious

-y

cloudy, really, windy

From a syntactic point of view we can distinguish the attributive and the

predicative use of an adjective. Most adjectives can be used attributively as well as

productively. Attribute adjectives are constituents of the noun phrase and precede the

noun head. Predicative adjectives function in the structure of the sentence as either

subject attribute or object attribute.

Examples:

Attributive

A nice car

a green door

That foolish idea

many witty remarks

Attributive adjectives normally precede the noun phrase head, but in some

cases they follow the noun head:

somebody important

the person responsible

something interesting

the tickets available

Predicative

subject attributive

The window is white.

Her plan seem excellent.

My coffee is hot.

object attributive

We painted the window white

We consider her plan excellent.

I prefer my coffee hot.

Most adjectives can be attributively as well as predicatively, such as brave,

calm, clever, hungry, and noisy.

This is a comfortable chair. (attributive)

This chair is comfortable.

(predicative)

I made the chair comfortable. (predicative)

Some adjectives can be used both attributively and predicatively, though there

are adjectives that can only be used in one of these ways.

Some adjectives are attributive only, such as chief, indoor, inner, latter, main,

nonsense, outdoor, outer.

Attributive only

Examples:

the inner court

the outer suburbs

sheer nonsense

an utter fool

the main cause

the upper story

Predicative only

Most adjectives beginning with a- are used predicatively only.

Examples:

asleep

awake

alive

afraid

alone

aware

Some adjectives can be both attributely and predicatively in one meaning, but

are restricted to the attributive function in another meaning:

Attributive and predicative

an old book

- that book is old.

real gold

- that gold is real.

a perfect room

- that room is perfect.

a true story

- that story is true

Attributive only:

a true hero

-that hero is true.

a perfect idiot

-that idiot is perfect.

a real hero

-that hero is real

the right woman

-that woman is right

1.4. Adverbs

Adverbs are used to modify a verb, an adjective, or another adverb:

1. Mary sings beautifully

2. David is extremely clever

3. This car goes incredibly fast

In 1, the adverb beautifully tells us how Mary sings. In 2, extremely tells us the

degree to which David is clever. Finally, in 3, the adverb incredibly tells us how fast the

car goes.

Before discussing the meaning of adverbs, however, we will identify some of

their formal characteristics.

Many adverbs are identified on the basis of derivational suffixes. Typical

derivational suffixes are:

-ly

:

heavily, fully, wisely

-ward(s)

:

afterward, homeward, upwards

-wise

:

clockwise, edgewise, lengthwise

On the other hand, not all words ending in ‘-ly’ are adverbs. For instance, words like

beastly, friendly, lively, lovely and lonely belong to the class of adjectives.

Only a small number of adverbs are characterized by the comparative and

superlative inflection. The majority of these are identical in form with adjectives, as seen

in the following.

Examples:

early

earlier

earliest

fast

faster

fastest

hard

harder

hardest

quick

quicker

quickest

well

better

best

badly

worse

worst

Syntactically speaking we can distinguish two major functions of adverbs. Firstly,

they function as adverbial or they modify the head in adjective and adverb phrases.

Secondly, they modify the head in adjective and adverb phrases.

When functioning as sentence constituents adverbs express such meaning as

time, place, manner and degree.

Examples:

The bus arrived yesterday.

They are leaving for Bangkok tomorrow.

He absolutely refused to travel.

A student has been studying attentively.

The prisoners were punished cruelly.

They can also express the attitude of the speaker towards what he is saying, as

follows:

Unfortunately, they seem to be mistake.

Honestly, they tried to call her.

Adverbs can also be constituents of phrases, where adverbs modify the head of

an adjective or adverb phrase.

Modifier of adjective phrase head or adverb phrase head

adjective phrase

adverb phrase

very interesting

almost always

exceptionally brave

hardly ever

very useful

rather quickly

really good

most obviously

truly astonishing

fairly well

Formal Characteristics of Adverbs

From our examples above, you can see that many adverbs end in -ly. More

precisely, they are formed by adding -ly to an adjective:

slow

quick

soft

sudden

gradual

Adjective

slowly

quickly

softly

suddenly

gradually

Adverb

Because of their distinctive endings, these adverbs are known as –ly Adverbs.

However, not all adverbs end in -ly. Note that some adjectives also end in -ly, including

costly, deadly, friendly, kindly, likely, lively, manly, and timely.

Like adjectives, many adverbs are Gradable, that is, we can modify them using

very or extremely:

softly

very softly

suddenly

very suddenly

slowly

extremely slowly

The modifying words very and extremely are themselves adverbs. They are

called Degree Adverbs because they specify the degree to which an adjective or

another adverb applies. Degree adverbs include almost, barely, entirely, highly, quite,

slightly, totally, and utterly. Degree adverbs are not gradable (extremely, very).

Like adjectives, too, some adverbs can take Comparative and Superlative forms,

with -er and -est:

Somyos works hard -- Somchai works harder -- I work hardest

However, the majority of adverbs do not take these endings. Instead, they form

the comparative using more and the superlative using most:

Adverb

Comparative

Superlative

recently

more recently

most recently

effectively

more effectively

most effectively

frequently

more frequently

most frequently

In the formation of comparatives and superlatives, some adverbs are irregular:

Adverb

well

badly

little

much

Comparative

better

worse

less

more

Superlative

best

worst

least

most

Adverbs and Adjectives

Adverbs and adjectives have important characteristics in common -- in particular

their gradability, and the fact that they have comparative and superlative forms.

However, an important distinguishing feature is that adverbs do not modify nouns, either

attributively or predicatively:

Adjective

Somsak is a happy child

Somsak is happy

Adverb

Somsak is a happily child

Somsak is happily

The following words, together with their comparative and superlative forms, can

be both adverbs and adjectives:

early, far, fast, hard, late

The following sentences illustrate the two uses of early:

Adjective

I'll catch the early train

Adverb

I awoke early this morning

The comparative better and the superlative best, as well as some words

denoting time intervals (daily, weekly, monthly), can also be adverbs or adjectives,

depending on how they are used.

We have incorporated some of these words into the following exercise. See if

you can distinguish between the adverbs and the adjectives.

2. Closed Classes

Closed classes (also called function words) contain relatively few words since

they do not allow the creation of new word. That is, it is not easy to form new articles or

pronouns. Closed class words tend to occur at or towards the beginning of the larger

units of which they are part; in this respect they are markers of the units they introduce.

The membership is unrestricted since they do not allow the creation of new

members.

2.2 Determiners

Nouns are often preceded by the words the, a, or an. These words are called

determiners. They indicate the kind of reference which the noun has. The determiner the

is known as the definite article. It is used before both singular and plural nouns:

Singular

the taxi

the paper

the apple

Plural

the taxis

the papers

the apples

The determiner a (or an, usually when the following noun begins with a vowel) is

the indefinite article. It is used when the noun is singular:

a taxi

a paper

an apple

The articles the and a/an are the most common determiners, but there are many others:

any taxi

that question

those apples

this paper

some apple

whatever taxi

whichever taxi

Many determiners express quantity:

all examples

both parents

many people

each person

every night

several computers

few excuses

enough water

no escape

Perhaps the most common way to express quantity is to use a numeral. We look at

numerals as determiners in the next section.

Numerals and Determiners

Numerals are determiners when they appear before a noun. In this position,

cardinal numerals express quantity:

one book

two books

twenty books

In the same position, ordinal numerals express sequence:

first impression

second chance

third prize

The subclass of ordinals includes a set of words which are not directly related to

numbers (as first is related to one, second is related to two, etc). These are called

general ordinals, and they include last, latter, next, previous, and subsequent. These

words also function as determiners:

next week

last orders

previous engagement

subsequent developments

When they do not come before a noun, as we've already seen, numerals are a

subclass of nouns. And like nouns, they can take determiners:

the two of us

the first of many

They can even have numerals as determiners before them:

five twos are ten

In this example, twos is a plural noun and it has the determiner five before it.

Determiner and Pronoun

There is considerable overlap between the determiner class and the subclass of

pronouns. Many words can be both:

Pronoun

This is a very boring book

That's an excellent film

Determiner

This book is very boring

That film is excellent

As this table shows, determiners always come before a noun, but pronouns are

more independent than this. They function in much the same way as nouns, and they

can be replaced by nouns in the sentences above:

This is a very boring book Ivanhoe is a very boring book

That's an excellent film

Witness is an excellent film

On the other hand, when these words are determiners, they cannot be replaced

by nouns:

This book is very boring Ivanhoe book is very boring

That film is excellent

Witness film is excellent

Personal pronouns (I, you, he, etc) cannot be determiners. This is also true of

possessive pronouns (mine, yours, his/hers, ours, and theirs). However, these pronouns

do have corresponding forms which are determiners:

Possessive Pronoun

The white car is mine

Yours is the blue coat

The car in the garage is his/hers

Sombat's house is big, but ours is bigger

Theirs is the house on the left

Determiner

My car is white

Your coat is blue

His/her car is in the garage

Our house is bigger than Sombat's

Their house is on the left

Definite and indefinite articles can never be pronouns. They are always

determiners.

The Order of Determiners

Determiners occur before nouns, and they indicate the kind of reference which

the nouns have. Depending on their relative position before a noun, we distinguish three

classes of determiners.

Pre-determiner Central Determiner Post-determiner Noun

I met

all

my

many

friends

A sentence like this is somewhat unusual, because it is rare for all three

determiner slots to be filled in the same sentence. Generally, only one or two slots are

filled.

Pre-determiners

Pre-determiners specify quantity in the noun which follows them, and they are of

three major types:

1. "Multiplying" expressions, including expressions ending in times:

twice my salary

double my salary

ten times my salary

2. Fractions

half my salary

one-third my salary

3. The words all and both:

all my salary

both my salaries

Pre-determiners do not normally co-occur:

all half my salary

Pre-determiners co-occur with determiners, normally preceding them:

all the boys

both these umbrellas

half Ratta’s time

If we say all boys the position is occupied by the Zero Article. Many of the

determiners and pre-determiners function like pronouns.

NP

Pre Det

both

NP

Det

N

these

umbrellas

In the above example, both predetermines the determiner these which in turn

determines umbrellas.

Central Determiners

The definite article the and the indefinite article a/an are the most common

central determiners:

all the book

half a chapter

As many of our previous examples show, the word my can also occupy the

central determiner slot. This is equally true of the other possessives:

all your money

all his/her money

all our money

all their money

The demonstratives, too, are central determiners:

all these problems

twice that size

four times this amount

Post-determiners

Cardinal and ordinal numerals occupy the post-determiner slot:

the two children

his fourth birthday

This applies also to general ordinals:

my next project

our last meeting

your previous remark

her subsequent letter

Other quantifying expressions are also post-determiners:

my many friends

our several achievements

the few friends that I have

Unlike pre-determiners, post-determiners can co-occur:

my next two projects

several other people

Post-determiners follow the determiners and precede the adjectives. While

adjectives can occur in any order, post-determiners have fixed positions. The following

three classes of post-determiners can be recognized.

Ordinals

Cardinals

Superlative/Comparative

first

one

more

second

two

most

third

three

fewer

next

many

fewest

last

few

less

final

several

least

Conjunctions

Conjunctions are used to express a connection between words. The most

familiar conjunctions are and, but, and or:

Paul and David

cold and wet

tired but happy

slowly but surely

tea or coffee

hot or cold

They can also connect longer units:

Paul plays football and David plays chess.

I play tennis but I don't play well.

We can eat now or we can wait till later.

There are two types of conjunctions. Coordinating Conjunction (or simply

coordinators) connect elements of `equal' syntactic status:

Paul and David

I play tennis but I don't play well

meat or fish

Items which are connected by a coordinator are known as Conjoins. So in ‘I play

tennis but I don't play well’, the conjoins are “I play tennis” and “I don't play well.”

On the other hand, subordinating conjunctions (or subordinators) connect

elements of `unequal' syntactic status:

I left early because I had an interview the next day

We visited Madame Tussaud's while we were in London

I'll be home at nine if I can get a taxi

Other subordinating conjunctions include although, because, before, since, till,

unless, whereas, whether

Coordination and subordination are quite distinct concepts in grammar. Notice,

for example, that coordinators must appear between the conjoins:

(Somjit plays football) and (Sommai plays chess)

And (Sommai plays chess) (Somjit plays football)

However, we can reverse the order of the conjoins, provided we keep the

coordinator between them:

Sommai plays chess and Somjit plays football

In contrast with this, subordinators do not have to occur between the items they

connect:

I left early because I had an interview the next day

Because I had an interview the next day, I left early

But if we reverse the order of the items, we either change the meaning completely:

I left early because I had an interview the next day

I had an interview the next day because I left early

or we produce a very dubious sentence:

I'll be home at nine if I can get a taxi

I can get a taxi if I'll be home at nine

This shows that items linked by a subordinator have a very specific relationship

to each other -- it is a relationship of syntactic dependency. There is no syntactic

dependency in the relationship between conjoins. We will explore this topic further when

we look at the grammar of clauses.

Auxiliary Verbs

In the examples of -ing and -ed forms which we looked at earlier, you may have

noticed that in each case two verbs appeared:

1. The old lady is writing a play

2. The film was produced in Hollywood

Writing and produced each has another verb before it. These other verbs (is and

was) are known as Auxiliary Verbs, while writing and produced are known as Main Verbs

or Lexical Verbs. In fact, all the verbs we have looked at on the previous pages have

been main verbs.

Auxiliary verbs are sometimes called Helping Verbs. This is because they may

be said to "help" the main verb which comes after them. For example, in The old lady is

writing a play, the auxiliary is helps the main verb writing by specifying that the action it

denotes is still in progress.

Auxiliary Verb Types

In this section we will give a brief account of each type of auxiliary verb in

English. There are five types in total:

Passive be

Progressive

be

Perfective

have

Modal

can/could

may/might

shall/should

will/would

must

Dummy Do

This is used to form passive constructions, eg.

The film was produced in Hollywood

It has a corresponding present form:

The film is produced in Hollywood

We will return to passives later, when we look at voice.

As the name suggests, the progressive expresses action in

progress:

The old lady is writing a play

It also has a past form:

The old lady was writing a play

The perfective auxiliary expresses an action accomplished in the

past but retaining current relevance:

She has broken her leg

(Compare: She broke her leg)

Together with the progressive auxiliary, the perfective auxiliary

encodes aspect, which we will look at later.

Modals express permission, ability, obligation, or prediction:

You can have a sweet if you like

He may arrive early

Paul will be a footballer some day

I really should leave now

This subclass contains only the verb do. It is used to form

questions:

Do you like cheese?

to form negative statements:

I do not like cheese

and in giving orders:

Do not eat the cheese

Finally, dummy do can be used for emphasis:

I do like cheese

An important difference between auxiliary verbs and main verbs is that

auxiliaries never occur alone in a sentence. For instance, we cannot remove the main

verb from a sentence, leaving only the auxiliary:

I would like a new job

I would a new job

You should buy a new car

You should a new car

She must be crazy

She must crazy

Auxiliaries always occur with a main verb. On the other hand, main verbs can

occur without an auxiliary.

I like my new job

I bought a new car

She sings like a bird

In some sentences, it may appear that an auxiliary does occur alone. This is

especially true in responses to questions:

Q. Can you swim?

A. Yes, I can

Here the auxiliary can does not really occur without a main verb, since the main

verb -- swim -- is in the question. The response is understood to mean:

Yes, I can swim

This is known as ellipsis -- the main verb has been ellipted from the response.

Auxiliaries often appear in a shortened or contracted form, especially in informal

contexts. For instance, the auxiliary have is often shortened to 've:

I have won the lottery - -> I've won the lottery

These shortened forms are called enclitic forms. Sometimes different auxiliaries

have the same enclitic forms, so you should distinguish carefully between them:

I'd like a new job ( = modal auxiliary would)

We'd already spent the money by then ( = perfective auxiliary had)

He's been in there for ages ( = perfective auxiliary has)

She's eating her lunch ( = progressive auxiliary is)

The Nice Properties of Auxiliaries

The so-called Nice properties of auxiliaries serve to distinguish them from main

verbs. Nice is an acronym for:

Negation

Inversion

Auxiliaries take not or n't to form the negative, eg. cannot, don't, wouldn't

Auxiliaries invert with what precedes them when we form questions:

I will see you soon - - >Will I see you soon?

Code

Auxiliaries may occur "stranded" where a main verb has been omitted:

John never sings, but Mary does

Emphasis Auxiliaries can be used for emphasis:

I do like cheese

Main verbs do not exhibit these properties. For instance, when we form a

question using a main verb, we cannot invert:

Damrong sings in the choir

- - > Sings Damrong in the choir?

Instead, we have to use the auxiliary verb do:

Damrong sings in the choir

- - > Does Damrong sing in the choir?

Semi-auxiliaries

Among the auxiliary verbs, we distinguish a large number of multi-word verbs,

which are called Semi-Auxiliaries. These are two-or three-word combinations, and they

include the following:

get to

seem to

be about to

happen to

tend to

be going to

have to

turn out to

be likely to

mean to

used to

be supposed to

Like other auxiliaries, the semi-auxiliaries occur before main verbs:

The film is about to start

I'm going to interview the Prime Minister

I have to leave early today

You are supposed to sign both forms

I used to live in that house

Some of these combinations may, of course, occur in other contexts in which

they are not semi-auxiliaries. For example:

I'm going to London

Here, the combination is not a semi-auxiliary, since it does not occur with a main

verb. In this sentence, going is a main verb. Notice that it could be replaced by another

main verb such as travel (I'm travelling to Lomsak). The word 'm is the contracted form

of am, the progressive auxiliary, and to, as we'll see later, is a preposition.

Interjection

An Interjection is a word added to a sentence to convey emotion. It is not

grammatically related to any other part of the sentence.

We usually follow an interjection with an exclamation mark. Interjections are

uncommon in formal academic prose, except in direct quotations.

Sometimes interjections are just sounds, exclamations, gasps, or shouts, more

like noises than regular words.

These are some common Interjections:

Aha

Ahem

All right

Gadzooks

Gee Whiz

Good

Gosh

Yippee

Hey

Hooray

Indeed

My Goodness

Nuts

Oh No

Oops

Ouch

Phew

Right on

Ugh

Dear me

Whoopee

Wow

Yikes

Yoo-hoo

Yuck

Summary

Linguists divide words into two classes:

1. Open Class

2. Closed Class

Words that belong to open class are those generally classified as nouns (e.g.

pen, book, boy, brandy), verbs (e.g. see, become, appear), adjectives (e.g. good,

painful, charming, tall) or adverbs (e.g. here, now, yesterday, calmly, soundly). These

words are said to belong to the open class because more and more words continue to

be added to this class. One can always coin new words to add to the existing stock of

words in this group. Thus, the membership of this group is open ended. English

vocabulary is continually being extended by new words belonging to this group.

Open Class Words

1. Nouns

Examples of nouns are girl, table, fire, thing, idea. It is often said that nouns are

‘naming’ words, used as the name of a person, animal, place and thing. Proper nouns

name particular places or persons (e.g. Samran, Somsak, Bangkok, Phetchabun). Other

nouns (like girl, thing) are called common nouns.

2. Verbs

Examples of verbs are sing, drive, go, love. It is often said that verbs are ‘doing’

words, words that mean actions performed by someone of something.

3. Adjectives

Examples of adjectives are good, bad, lovely, friendly. It is often said that

adjectives are words which ‘describe’ or tell you something about the noun.

4. Adverbs

Examples of adverbs are now, then, often, calmly, actually, today. It is often said

that adverbs are words which tell you something about a verb, adjective or indeed other

adverbs. In the following examples, the words in bold type are adverbs:

The little boy ran quickly in the room.

The woman was very beautiful.

Tai Orathai sang very well.

The close class, on the other hand, has a fixed number of words in it. No new

words are added to it. The closed class includes word generally classified as

Determiners (e.g. a, an, the, some, any, this), Pronouns (e.g. I, me, you, we) Prepositions

(e.g. in, at, on, upon, near, far), Conjunctions (e.g. and, or, but, when, because), Modals

or Auxiliary (e.g. will, shall, can) numeral (e.g. one, first) and Interjection (e.g. Ugh!,

Alas!).

Closed Class Words

1. Determiners

Examples of determiners are the, a, an, this, that, some, any, all. Determiners

include those words known as article:

‘the’ is called the definite article, because you are talking about a definite,

particular example of a thing.

‘a, an’ is called indefinite article, because you do not mean any definite,

particular example.

Determiners also include demonstratives, e.g. this, these, etc.

Determiners function as specifying modifiers of nouns. For example, in the

phrases:

the mango

this boy

some oranges

these pens

the determiners the, this, some, and these specify the particular mango, boy,

oranges, pens being referred to.

2. Pronouns

Examples of pronouns are I, me, you, it, they, etc. It is often said that pronouns

‘replace’ nouns; for instance, in the sentence.

The good boy ate the mango.

We can use the pronouns ‘he’ and ‘it’ to replace ‘The good boy’ and ‘the mango’:

He ate it.

3. Prepositions

Examples of prepositions are in, by, with, from, to, for, etc. Prepositions are

words placed in front of a noun or pronoun to show the relationship of that noun of

pronoun to other words in the sentence. In the following examples, the words in bold

types are prepositions:

in the house

by the brook

on the table

with the girl

to her

by him

through it.

4. Conjunctions

Examples of conjunctions are and, but, that, if, when, because, etc. Conjunctions

are words which link other elements together. In the following examples, the words in

bold type are conjunctions:

Tosapol was a short man but Somyos was tall.

Veerawan ate her food because she liked vegetables.

5. Modals or Auxiliary Verbs

Examples of auxiliary verbs are can, may, will, have, be, etc. Auxiliary (or

‘helping) verbs are those common words which modify the lexical verb within the verb

phrase. They are the short verbs that help to form different tenses, telling you when

something happened, and also help to form questions. In the following examples, the

words in bold type are auxiliary verbs:

The woman was frying eggs.

Veerawan should eat her food.

Will you drink your coffee?

The dog has chewed the paper.

6. Numerals

Examples of numerals are one, two, first, second etc, and they are fairly easy to

recognize. There are two kinds of numerals: cardinal and ordinal. Cardinal numbers are

one, two, three etc.; ordinal numbers are first, second, etc.

7. Interjections

Examples of interjections are oh!, ah!, etc. It can be said that interjections are

exclamations expressing emotion.

The following is an illustration of classes of word.

Word Class

Open Classes

-

Nouns (boy, hotel, day)

Verbs (run, drink, play)

Adjectives (good, low, high)

Adverbs (quickly, completely)

Closed Classes

-

Pronouns (he, she, it, we, they)

Determiners (a, an, the, this, that, these)

Prepositions (in, on, at, under)

Conjunctions (and, but, because etc.)

Auxiliaries (will, must, can, may etc.)

Numerals (one, four, first, forth etc.)

Interjection ( Heaven!, Alas!)