BY: Prof. KS RAMACHANDRAN - Finance Commission, India

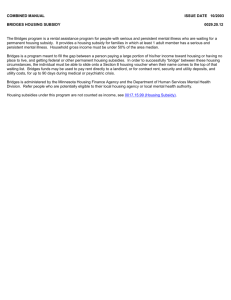

advertisement