Creating Participatory Inequalities across Generations and among

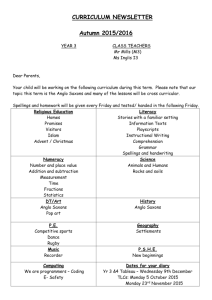

advertisement