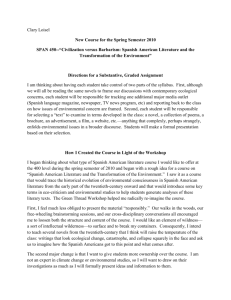

Outline for the Curriculum Proposal

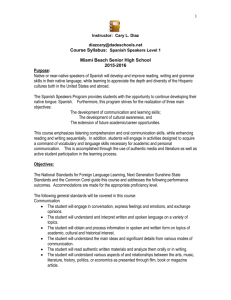

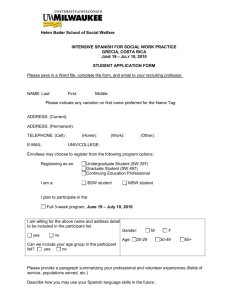

advertisement