Apprenticeships for young people

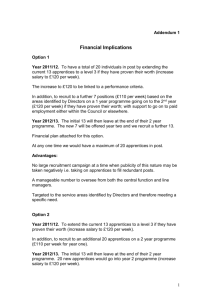

advertisement