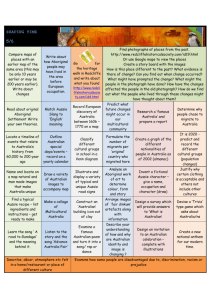

Chapter 2 The influence of Religion in Australian Society from

advertisement