GeoCanada abstract - University of Manitoba

advertisement

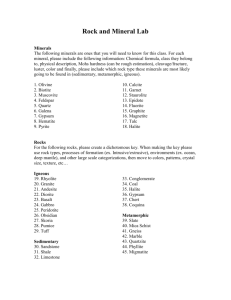

Gypsum Rosettes in Southern Manitoba: Tools for Environmental Analysis and Public Awareness J. Young, N. Chow, I. Ferguson, V. Maris, D. McDonald, D. Benson, N. Halden (University of Manitoba) Dept. of Geological Sciences, 125 Dysart Road, Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N2, Gaywood Matile (Manitoba Industry, Trade and Mines) GeoCanada 2000 - The Millennium Geoscience Summit, Calgary, Alberta, May 2000 ____________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT: Gypsum crystals have been found in Quaternary Lake Agassiz clays at numerous locations in southern Manitoba (Matile and Betcher, 1998). “Ore-grade” concentrations of gypsum (selenite) rosettes along the Red River floodway have been commercially exploited by AMA Mines. Several researchers and students from the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Manitoba are conducting an ongoing, multidisciplinary project to study the gypsum rosettes at several localities in southern Manitoba (Fig. 1). In co-operation with Dr. Anne Walker, a teacher at Glenlawn Collegiate in Winnipeg, chemistry and physics students in Grades 11 and 12 are actively participating in the research as part of an outreach program in the Department of Geological Sciences. Stratigraphy The proglacial Lake Agassiz succession in southern Manitoba has been subdivided into three units: Agassiz Units 1 and 2, unconformably overlain by Agassiz Unit 3 (Teller, 1976). Units 1 and 2 cannot be differentiated at the investigation sites and are herein referred to as Agassiz Unit 1&2. Agassiz Unit 1&2 is characterized by dark grey and brown, massive clay. Silt and clay thin-beds are observed locally and show soft-sediment deformation. Sub-vertical fractures crosscut Agassiz Unit 1&2. The overlying Agassiz Unit 3 is characterized by grey to brown, thinly interbedded and interlaminated silt and clay, showing planar and ripple-cross lamination. In Agassiz Unit 1&2, gypsum rosettes, up to 10 cm in diameter, have been found in the upper 10 m in localized concentrations or associated with fractures; the maximum Figure 1. Location map showing Lake depth of occurrence of rosettes is unknown due to sampling Agassiz basin (blue), known locations of limitations. There are also mm-size nodules of finely gypsum rosettes () and an iceberg-scour crystalline white gypsum that occur near concentrations of location (). rosettes or in thin beds. In Agassiz Unit 3, gypsum occurs as fracture-filling or laminated alabaster, small rosettes and individual crystals. Rosette types and petrography In this study, three types of gypsum rosettes have been recognized on the basis of habit and spatial arrangement of the crystals. Type T rosettes are characterized by colourless to pale-yellow, tabular crystals. These rosettes occur in Agassiz Unit 1&2 and have only been observed to date at the Red River floodway site where there have been deep excavations for “ore-grade” rosettes. They are most abundant at ~1-2 m below the contact between Agassiz Unit 1&2 and Unit 3 but they have been collected from depths up to 10 m. Type L rosettes are characterized by amber to pale-yellow lenticular crystals. These rosettes have been observed at all sites studied to date (Birds Hill, Red River floodway and Letellier), Gypsum rosettes in southern Manitoba occurring in fractures near the contact between Agassiz Unit 1&2 and Unit 3. Type B rosettes are solitary or aggregate balls of finer crystalline, amber to pale-yellow lenticular crystals. They occur in the upper part of Agassiz Unit 1&2 and in Agassiz Unit 3 at all study sites. Crystals comprising Type T and L rosettes show irregularly concentric zoning that is readily observable using epi-fluorescence (epi-FL) microscopy (436 nm, blue-violet filter): an inner, dark-blue fluorescing zone; and an outer, light-green fluorescing zone, which may show thin, concentric banding (Fig. 2). Geochemistry Crystals from selected rosettes were analyzed using inductively-coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES). The major element chemistry is similar for both Type L and T rosettes but the concentration of Ca is significantly less than that expected in stoichiometric gypsum. Trace abundances of Sr and Na have also been detected; Type L rosettes have higher Sr and Na concentrations than those from Type T rosettes. Furthermore, preliminary analyses using proton-induced x-ray spectrometry (-PIXE) reveal that the inner, darkblue fluorescing zone of crystals from both Type T and Type L rosettes have significantly higher Sr concentrations than the outer, light-green fluorescing zone. Figure 2. Epi-FL photomicrograph of crystal from Type L rosette, showing concentric zoning with an inner (I) and outer (O) zone. Oxygen and sulfur isotope analyses of gypsum show variations between the different sites that have been sampled. Type T and L rosettes from the Red River floodway and Birds Hill sites have 18O and 34S values for gypsum sulfate that overlap (+2.2 to +8.5‰ SMOW and -14.7 to -12.8‰ CDT, respectively); Type L rosettes have the highest values. In contrast, Type L and B rosettes from the Letellier site have 18O values that range from -2.5 to -3.8‰ SMOW, with 34S values that are slightly lower than those from the previous two sites. Within each site, the different rosette types have different isotopic composition. Nonetheless, based on current data, there appears to be no systematic correlation between rosette type and location. The stratigraphic distribution and preliminary geochemical analyses of the gypsum rosettes, in conjunction with previous ground-water data for Agassiz clays (Day, 1977; Pach 1994), suggest that gypsum formation was associated with lowering of the piezometric surface, followed by infiltration and ponding of meteoric water. Isotopic data from the three study sites further suggest an organic sulfur or sulfide origin for the sulfate, and in situ formation of the sulfate. Geophysics Geophysical surveys have been done at the Red River floodway and Letellier sites in order to provide more information on the genesis of the gypsum rosettes and to assess the application of geophysics as an exploration tool for new deposits. The physical properties of the Agassiz units, as well as overlying and underlying units, have been characterized in a number of geotechnical studies on the Winnipeg area (e.g. Baracos, 1977; Graham and Shields, 1985). Seismic refraction surveys conducted during the construction of the Red River floodway (Hobson et al., 1964) defined the seismic velocity response of the different geological units and revealed considerable variation in the depth to bedrock along the floodway associated with karstification of the bedrock. Near the floodway site, the bedrock is at 22 m depth but there is a sharp decrease to 12 m depth, Gypsum rosettes in southern Manitoba several hundred metres to the north. Previous geoelectric studies in the Winnipeg area have indicated that the conductivity of the upper several metres of soil is ~100 mS.m-1, and the conductivity of the Agassiz units is 125-200 mS.m-1. Surveys at the Red River floodway and Letellier sites. Geophysical surveys at the Red River floodway site included electromagnetic/electrical (EM31, EM38, DC-resistivity, PROTEM47) and seismic refraction methods. The seismic refraction results resolved the thickness of the soil layer, the combined thickness of the clay units, and the thickness of the till, but not resolve the interface between Agassiz Unit 1&2 and Unit 3. Small-scale EM measurements in the excavation pit revealed the conductivity of the Agassiz Unit 1&2 to be 200 mS.m-1 and that of Agassiz Unit 3 to be 120-150 mS.m-1. Surface DC resistivity measurements identified three layers corresponding to more resistive soil and Agassiz Unit 3, conductive Agassiz Unit 1&2, and more resistive till/bedrock. One significant control on lateral variations in the Agassiz clays is iceberg scouring of Agassiz Unit 1&2. The scouring produced lowangle faults below the scour trough, which extended at least 3 m below the scour, and high-angle normal faults outside the scour (WoodworthLynas & Guigné, 1990). The scours can be recognized on the presentday ground surface as linear features that are on the order of 100 m wide and have topographic relief of several decimetres. Shallow troughs at the margins of the scours have been deepened locally by farmers to control surface runoff. The scours appear to influence the near-surface hydrology, and the associated deeper structures, particularly the normal faults, likely 190 180 170 160 150 140 130 120 110 100 90 80 70 Figure 3. EM31 horizontal and vertical dipole mode contours for the east berm of the Red River floodway site. Apparent Conductivity (mS/m) Interpretation and discussion. Full interpretation of the geophysical results requires a detailed understanding of the electrical conductivity of the Agassiz units. At the smallest-scale, factors controlling conductivity include porosity, saturation, groundwater salinity, and clay mineralogy. An initial sampling program at the Red River floodway site has indicated grain-size and mineralogical variations across the anomaly. Sampling studies are planned for the Letellier site. Horizontal Vertical 260 250 240 230 220 210 200 190 180 170 160 150 140 130 120 110 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 10 20 30 0 10 20 30 Easting (m) Easting (m) Excavation Pit Initial geophysical surveys at the Letellier site have revealed a conductive anomaly coincident with the gypsum deposit. EM31 readings increase from 100 mS.m-1 in background areas to 250 mS.m-1 in the anomaly. Conductivity readings correlate inversely with, and may be partially controlled by, a corresponding 75 cm variation in surface topography. Readings in the dugout, where gypsum rosettes were collected, are in the range of 190-220 mS.m-1, similar to those from the excavation pit at the Red River floodway, but less conductive than the overlying units. At both the floodway and Letellier sites, there is an indication that the location of the gypsum deposits is related to linear conductive features in the overlying units. Northing (m) The most surprising results of the geophysical surveys were the lateral variations in the electrical response. Surveys using an EM31 in horizontal dipole mode (penetration 3 m) and vertical dipole mode (5 m), DC resistivity profiling (5-10 m), and time-domain electromagnetics (5-20 m) all revealed a broad resistive zone containg a more narrow conductive zone coincident with the excavation pit (Fig. 3). These observations suggest that the location of the deposit may be related to structures within the overlying Agassiz Unit 3. Gypsum rosettes in southern Manitoba influence the deeper hydrological conditions. In the absence of vertical structures, such as faults, the Agassiz clays form an aquitard, with low hydraulic permeability across the laminae (Baracos et al., 1980). The geophysical results suggest a relationship between gypsum rosette accumulations and linear anomalies in near-surface units; iceberg scours can produce such linear anomalies. Hence, we have started to investigate the geophysical response of iceberg scours in the Agassiz clays. To date, geophysical surveys have been completed over two scours in the Lorette area that were investigated by Woodworth-Lynas & Guigné (1990). Electromagnetic survey results show conductivity variations of a magnitude and form similar to those observed at the gypsum sites. Outreach High-school science education in Manitoba largely neglects the geosciences. To broaden the scope of high-school science curricula, we have teamed up with interested chemistry and physics students from Glenlawn Collegiate in Winnipeg to study the gypsum rosettes. The students work with us in an active research environment. At the same time, Glenlawn Collegiate has developed a program that links their students with industry, government and academia. Important issues in running this outreach program are: (1) student participation at an appropriate level – students are given the broad background of the project and assigned specific, but challenging, research objectives; (2) “hands-on” use by students of state-of-the-art field and lab equipment and techniques; and (3) scheduling research sessions that consider the timetables of both the researchers and students. Over the past year, Glenlawn students have participated in: (1) field work including gypsum sampling and electromagnetic and seismic surveys; (2) sample preparation for petrography; (3) characterization of the textural relationships between gypsum and host clays using a binocular microscope and scanning electron microscope; and (4) identification of clay minerals using powder X-ray diffraction methods.