Congressional hearing for Air Force Tanker

advertisement

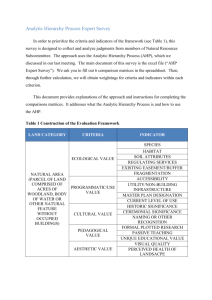

THE ANALYTIC HIERARCHY PROCESS AND MULTI-CRITERIA PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS Stephen L. Liedtka Assistant Professor of Accounting Lehigh University Forthcoming in the November/December 2005 issue of Cost Management EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This paper describes how the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), a popular decisionsupport methodology, is particularly well-suited to the challenges of implementing a multicriteria performance management system (MCS) such as the Balanced Scorecard. In doing so, the paper describes AHP methodology in detail, and demonstrates AHP by using the method to create a basic MCS for a major airline. Additionally, the paper reports overall airline performance scores generated by the MCS and compares the derived scores to the results from two competing approaches. Of the three sets of results, the AHP-based performance scores correlate highest with annual stock market returns, providing some evidence that AHP yields a superior model for linking strategy to shareholder wealth. Acknowledgments: The author gratefully acknowledges assistance from Frank Alt, Larry Bodin, Dick Durand, Larry Gordon, Jim Largay, Marty Loeb, Ella Mae Matsumura, and Expert Choice, Inc. Address for correspondence: Rauch Business Center, Lehigh University, 621 Taylor Street, Bethlehem, PA 18015, USA. E-mail: SLL7@Lehigh.edu. THE ANALYTIC HIERARCHY PROCESS AND MULTI-CRITERIA PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION Academics and practitioners long have argued that the traditional use of a single financial measure of firm performance, such as return on investment or residual income, can result in excessive focus on the short-term at the expense of long-term firm health. To promote a comprehensive view of the firm, therefore, researchers advocate the replacement of traditional single-measure systems with sets of financial and nonfinancial performance measures that reflect all vital firm activities. Peter Drucker, for instance, recommended a “balanced stress on objectives” such as market standing, innovation, productivity, physical and financial resources, profitability, manager performance and development, worker performance and attitude, and public responsibility.1 More recently, the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) has gained great popularity by reviving and significantly refining the “balanced stress” concept. Use of a multi-criteria system (MCS) necessitates frequent and often difficult comparisons. Decision makers, for instance, must consider the relative importance of chosen objectives whenever tradeoffs are necessary due to limited firm resources or the existence of inverse relationships among the objectives (e.g., certain cost vs. quality decisions). Further, assessment of overall firm or subunit performance at the end of a period necessitates that decision makers somehow reconcile measurements of the multiple criteria, which vary in nature (e.g., customer-related vs. human resource-related), time frame (historical vs. future-oriented), and measurement unit (e.g., dollars vs. time). 1 The lack of a formal method for prioritizing and comparing strategic objectives and measures limits the usefulness of the BSC and other MCS. Without reliable weightings of strategic objectives, for instance, an MCS does not precisely communicate the firm’s strategy, including the intensity of effort that should be devoted to each objective. In addition, for performance evaluation, lack of a formal decision-support system leaves individuals with an extremely difficult judgment task. In such cases, extant research demonstrates that decisionmakers may take suboptimal steps to reduce their cognitive burden. Decision-makers, for instance, show a tendency to ignore BSC measures that are unique to a subunit, choosing instead to consider only those measures that are common across divisions.2 This paper explains how the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), a popular decisionsupport methodology, is ideally suited to the challenges of implementing an MCS. In doing so, the paper describes AHP methodology in detail, and demonstrates AHP by using the method to create a basic MCS for a major airline. Additionally, the paper reports overall airline performance scores generated by the MCS and compares the derived scores to the results from two competing approaches. Of the three sets of results, the AHP-based performance scores correlate highest with annual stock market returns, providing some evidence that AHP yields a superior model for linking strategy to shareholder wealth. THE ANALYTIC HIERARCHY PROCESS AHP is a popular method for assessing multiple criteria and deriving priorities for decision-making purposes. Major companies (e.g., Ford, General Electric), public accounting firms (e.g., KPMG, PricewaterhouseCoopers) and government agencies (e.g., United States Treasury Department, United States State Department) already utilize AHP for various purposes. Additionally, academics have employed AHP in over 2,000 studies. In the accounting literature, 2 for instance, researchers have applied AHP to a number of complex problems such as analytical review, internal control evaluation, and assessment of management fraud “red flags”. The number and diversity of AHP applications continues to grow because AHP is simple to employ, and yet is based upon the well-established and theoretically sound techniques of (1) structuring problems into hierarchies, (2) reducing complex judgments into a series of pairwise relative comparisons, (3) using redundant judgments to assess participant consistency, and (4) using an eigenvector method for deriving weights3 As discussed below, these techniques are directly applicable to problem of prioritizing and comparing strategic objectives for an MCS. The AHP Hierarchy AHP begins with the organization of performance criteria into a “hierarchy.” As applied to organizational performance measurement, this means that the firm must relate overall performance to strategic objectives and individual performance measures. A BSC, for instance, is a hierarchy and is perfectly suited for AHP. To demonstrate, Figure I uses a hierarchical format to present a portion of the BSC used by the City of Charlotte, North Carolina’s Department of Transportation (CDOT) 4 [INSERT FIGURE I HERE] One purpose of the AHP hierarchy is to structure and simplify the decisions discussed in the next section. Just as importantly, the process of designing a hierarchy and selecting performance measures forces the firm to link each performance measure to a strategic objective and, ultimately, each strategic objective to overall performance. Indeed, both BSC and AHP proponents cite the process of clarifying and translating goals into a concrete set of relationships as a major benefit. Because much guidance already exists regarding the structure of BSCs and other hierarchies, I proceed without further discussion to the next step in AHP. 3 Pairwise Relative Comparisons The second step in applying AHP to performance measurement is for one or more knowledgeable experts to make pairwise assessments of the relative importance of the items on each level of the hierarchy. Referring to the lowest level of CDOT’s BSC hierarchy in Figure I, for example, the expert(s) must compare the importance of “Repair Response” relative to “Travel Speed” as they relate to the strategic objective of “Maintaining the Transportation System.” AHP users typically employ a relative importance scale such as the following to record their judgments: 1 “Repair Response” and “Travel Speed” are equally important with respect to “Maintaining the Transportation System”. 3 (1/3) “Repair Response” is weakly more (less) important than “Travel Speed” with respect to “Maintaining the Transportation System”. 5 (1/5) “Repair Response” is strongly more (less) important than “Travel Speed” with respect to “Maintaining the Transportation System”. 7 (1/7) “Repair Response” is very strongly more (less) important than “Travel Speed” with respect to “Maintaining the Transportation System”. 9 (1/9) “Repair Response” is absolutely more (less) important than “Travel Speed” with respect to “Maintaining the Transportation System”. The relative importance scale allows the user to refine judgments by selecting numbers between 0 and 9 — 1.5, 2.3 and so forth — as necessary. As applied to the implementation of an MCS, the relative importance scale has several advantages over other methods for recording judgments. First, because the scale allows comparison of items measured in different units, such as dollars vs. time, it is ideal for comparing the diverse items within an MCS. Second, humans are more capable of making relative judgments than absolute judgments. Third, unlike many absolute judgments, the relative importance judgments yield ratio-scale data, which is more flexible and meaningful than ordinal 4 or interval data. It is mathematically appropriate, for instance, to average the relative importance judgments of multiple members of an MCS design team. Finally, and most importantly, in situations where results are verifiable, the relative importance scale yields extremely accurate weighting systems. After comparing the importance of “Repair Response” and “Travel Speed”, the expert separately compares the importance of “Repair Response” relative to “High Quality Streets” and “Travel Speed” relative to “High Quality Streets.” After comparing the performance measures under each strategic objective, the expert compares each of the six strategic objectives, one pair at a time. For instance, the expert compares the importance of "Maintaining the Transportation System” relative to “Operating the Transportation System”. Finally, the expert compares, again one pair at a time, the importance of the four scorecard perspectives. A key benefit of the pairwise comparison approach is that it significantly reduces the computational burden on the individual making judgments. Without the pairwise comparison approach, for instance, expert(s) at CDOT must simultaneously estimate the relative importance of all six customer-related strategic objectives. Indeed, I selected the CDOT BSC due to its relative simplicity. In other BSC situations, experts might need to simultaneously compare ten, fifteen or more items. For example, the company called “Rockwater” by Kaplan and Norton calculates 16 different measures of customer satisfaction.5 The use of a hierarchy further simplifies the judgment process by ensuring that the expert(s) need not compare excessively heterogeneous performance measures. The CDOT BSC hierarchy, for instance, does not require experts to compare directly the importance of an operational measure such as "Repair Response” to measures of CDOT’s financial perspective such as “Money Received from Non-city Sources”. 5 Redundant Judgments and the Consistency Ratio A critical advantage of AHP is its ability to measure the extent to which expert judgments are consistent. Logically, if an expert rates item A twice as important as item B and item B twice as important as item C, then the expert should rate item A four times as important as item C. To the extent that the expert violates this logic, a measure termed the “consistency ratio” (CR) increases. An obvious benefit of the CR is that it highlights careless errors in judgment. Additionally, the CR contributes to the learning process by revealing to an expert his or her unconscious bias in one or more pairwise comparisons. In most applications, experts should revisit their pairwise comparisons when the CR exceeds 0.10. Roughly speaking, a CR greater than 0.10 indicates that there is a ten percent likelihood that the expert judgments were random. Software, such as Expert Choice©, automatically calculates CRs for the full set of pairwise comparisons as well as the subset of pairwise comparisons within each level of the hierarchy, thus simplifying the identification of any problematic judgments. In sum, while scales such as the relative importance scale might not be precise, the use of redundant judgments and CRs lead to the derivation of highly accurate priorities. Eigenvector Method for Deriving Priorities Once the pairwise comparisons are complete, software calculates relative weights for all items at all levels of the hierarchy. Though the matrix algebra involved in the calculation of weights can be complex, the logic is straightforward. Assume, for instance, that CDOT rates “High Quality Streets” twice as important as both “Repair Response” and “Travel Speed”. Weights for those measures would be 50 percent, 25 percent and 25 percent, respectively, for purposes of assessing the “Maintain the Transportation System” strategic objective. The 6 complexity arises when there are small, and thus acceptable, inconsistencies in the pairwise comparisons. In such cases, the matrix algebra yields weightings that minimize the impact of those inconsistencies. Figure II presents the CDOT BSC hierarchy with hypothetical AHP weights. CDOT could aggregate or disaggregate these weights as necessary. For example, CDOT could assess performance regarding the customer perspective in terms of the six strategic objectives. Alternatively, CDOT could assess the “Customer Perspective” in terms of individual performance measures. If “Repair Response” is 25 percent of “Maintaining the Transportation System” which, in turn, is 20 percent of the “Customer Perspective”, “Repair Response” receives a weight of 25 percent * 20 percent = 5 percent for purposes of evaluating the “Customer Perspective”. [INSERT FIGURE II HERE] As noted earlier, firms need reliable weightings to communicate strategy precisely and to measure overall performance. In addition, the ability to weight and aggregate performance measures via an AHP-based MCS gives firms the ability to test their strategic hypotheses. If a firm’s overall goal is to achieve superior market returns, for instance, the firm can test how highly their aggregate MCS score is correlated with those returns. To the extent that achievement of MCS objectives is not consistent with achievement of firm goals, the firm has evidence that its strategy might need adjustment. Furthermore, to facilitate adjustments, the firm could generate ex post ideal weightings for comparison to the ex ante model. Similarly, the firm can perform sensitivity analyses to determine how incremental improvements on individual objectives might impact overall results. 7 APPLICATION OF AHP TO MAJOR AIRLINE PERFORMANCE To demonstrate the process by which firms can derive weights and calculate aggregate performance scores, I now discuss the application of AHP to the problem of creating a basic MCS for a major hub-and-spoke airline. A “major airline” is defined here as one with at least one percent of total domestic (U.S.) scheduled-service passenger revenues. A hub-and-spoke strategy involves flying passengers with different destinations to a central airport, or hub, from which point the airline flies passengers on connecting flights to their destinations. The Airline AHP Hierarchy Because the input and judgments of an expert were essential, I held two interviews during January 1999 with the former president and chair of a major US airline. We began with a broad set of 13 airline strategic objectives identified by prior research. The expert had no additions to the list, but rather concurred that the strategic objectives are comprehensive and reflect the vital aspects of airline performance. When constructing a more extensive MCS, firms can use brainstorming sessions of key personnel from each of the relevant firm levels to identify possible objectives, subobjectives, etc. We next employed a simple AHP hierarchy, shown in Figure III, which separates financial performance objectives from nonfinancial performance objectives. This approach is consistent with academic literature, which frequently highlights these two broad performance measure categories. More importantly, the expert believed that the hierarchy was logical, and was comfortable making all of the resulting pairwise comparisons. During the hierarchy design process, however, the nonfinancial performance objective, “Passenger Safety,” was eliminated. The expert revealed that passenger safety is of such overriding importance that its inclusion completely obscures the importance of other strategic objectives. That is, passenger safety will 8 receive 100 percent of the weight if included in the analysis. Further, the former chairperson opined that, because passenger safety is a dominant priority for every major airline, it is not a useful characteristic for distinguishing among those carriers. This is consistent with the low fatality rate of airline travel relative to other forms of transportation, as well as research that suggests that accidents are rare and random occurrences within the set of major airlines. The September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York, Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania appear to have increased the importance to airlines of passenger safety even further. [INSERT FIGURE III HERE] Pairwise Comparisons No adjustments to the expert’s pairwise comparisons were necessary as no consistency ratio exceeded the recommended 0.10 ceiling. The highly consistent initial judgments suggest that the expert understood the task well and had firm, replicable views about the relative importance of the various criteria. Beyond facilitating the expert’s judgments, the pairwise comparison approach results in a more defensible MCS since “it is difficult to justify weights that are arbitrarily assigned, [but]it is relatively easy to justify judgments and the basis (hard data, knowledge, experience) for the judgments.”6 Further, when groups design an MCS, differences in pairwise comparisons between individuals highlight the specific sources of disagreement. To the extent that debate does not resolve such disagreements, facilitators can average the ratio-level judgments of group members as noted earlier. Ultimately, the ability of AHP to provide justifiable results and facilitate group participation can increase acceptance of the resulting weighting systems. 9 Weightings Figure IV presents relative importance weightings for the airline MCS that resulted from the expert’s pairwise comparisons. As emphasized earlier, such weightings are valuable in and of themselves since they communicate firm strategy to employees more precisely than a collection of unprioritized objectives. One of the many interesting observations is the strong preference for “Cash Flow” over “Return on Investment” as an indicator of periodic performance. In part, this reflects problems in interpreting accounting returns due to inconsistencies among airlines in leasing fixed assets. More importantly, however, the focus on “Cash Flow,” “Financial Leverage” and “Short-term Liquidity,” reflects the unstable nature of airline financial performance. In short, the industry expert considered it paramount that an airline have a limited amount of debt and sizeable cash flow and liquidity to withstand periodic downturns. Indeed, despite their dominance, the major airlines clearly are not immune from economic trouble. During 1991, for instance, the recession and Gulf War fuel price increases produced a particularly harsh year that led to the bankruptcies of Eastern Airlines and Pan American Airlines. More recently, cash flow, leverage and shortterm liquidity all have influenced the ability of airlines to weather the impact of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, which resulted in increased operating costs and decreased passengers. [INSERT FIGURE IV HERE] As one expects popular arguments for nonfinancial performance measures to predict, the expert gave “Passenger Volume,” “Labor Efficiency” and “Fixed Asset Efficiency” relatively high weights. The expert did not weight “On-time Performance” and “Customer Satisfaction” highly, however, in part due to his belief that service quality levels are near the point where additional investment is not cost-beneficial. Moreover, excessively high performance on service 10 quality measures actually may come at the expense of customer satisfaction. For example, airlines often accommodate passengers who arrive less than ten minutes before scheduled departure time although doing may result in late arrivals. In terms of customer satisfaction, not allowing tardy ticketed passengers to board might be more egregious than slightly delaying punctual passengers. Airline Performance Scores The next step was to calculate overall airline performance scores for the five-year period 1999-2003 by directly inputting standardized values for each performance measure into the AHP-derived weighting scheme. Although the optimal MCS should vary between firms, I applied the same AHP-based airline MCS to all six major hub-and-spoke airlines that were solvent throughout the study period. This approach disguises the identity of the specific airline used to derive the MCS. Further, due to the oligopolistic nature of the industry and the highly similar strategies of the study airlines, I posit that the optimal MCS does not vary significantly between those airlines. In general, results presented in the paper are consistent with this supposition. To provide evidence regarding the external validity of the airline MCS, I next correlated the AHP-based aggregate performance scores with annual market returns, since maximizing shareholder wealth is the typical overall goal of an organization. For comparison purposes, I also correlated market returns with two competing measures of overall performance: (1) cash flows (since the expert rated cash flows as the single most important criterion for airlines); and (2) an aggregate calculated by equally weighting the objectives in the AHP hierarchy. Results (Table 1) provide strong initial support for the derived weighting scheme as the AHP-based performance scores are significantly correlated with annual market returns for five of 11 the of the six airlines. Further, for five of six cases, market returns correlate higher with the AHP-based performance scores than with cash flows; and in all six cases the market returns correlate higher with the AHP-based scores than with the aggregate calculated by equally weighting objectives. Of the three approaches to performance management, therefore, the AHPbased MCS appears to link strategy to shareholder wealth most accurately. [INSERT TABLE 1 HERE] While the correlation of AHP-based performance scores with market returns provides some external validation of the airline MCS, it is important to understand that an initial MCS is based upon strategic hypotheses that should evolve as a firm gathers feedback over time. AHP facilitates such MCS evolution by allowing decision-makers to periodically revisit and fine-tune their relative importance judgments. This is in contrast to the equal weighting of measures and single measure approaches to performance management, which do not allow for variation in the importance of objectives. The performance of an AHP-based MCS, therefore, should improve over time relative to systems that weight objectives equally or only employ a single measure. CONCLUSION AHP is a well-established, theoretically sound methodology that firms can easily adapt for the purpose of generating and maximizing the utility of an MCS. The successful application of AHP described in this paper demonstrates the usefulness of the method and provides insight into the relative importance of strategic objectives for the airline industry. 12 NOTES 1 Drucker, P.M. (1954). The Practice of Management. New York: Harper & Row. 2 Lipe, M.G. and Salterio, S. (2000). The Balanced Scorecard: Judgmental Effects of Common and Unique Performance Measures. The Accounting Review 75 (3), 283-298. 3 Forman, E.H. and Selly, M.A. (2001). Decision By Objectives: How to Convince Others that You Are Right. New Jersey: World Scientific. 4 The CDOT Balanced Scorecard was adapted from Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (2001). The Strategy-Focused Organization. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. 5 Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. 6 Forman and Selly, p. 45. 13 FIGURE I Balanced Scorecard for the Charlotte, North Carolina Department of Transportation OVERALL PERFORMANCE FINANCIAL PERSPECTIVE CUSTOMER PERSPECTIVE INTERNAL PERSPECTIVE LEARNING PERSPECTIVE Strategic Objective 1 Strategic Objective 2 Strategic Objective 3 Strategic Objective 4 Strategic Objective 5 Strategic Objective 6 Maintain the Transportation System Operate the Transportation System Develop the Transportation System Determine the Optimal System Design Improve Service Quality Strengthen Neighborhoods Performance Measure 1 Performance Measure 2 Performance Measure 3 Repair Response Travel Speed High Quality Streets 14 FIGURE II Hypothetical Weights for the Charlotte, North Carolina Department of Transportation Balanced Scorecard OVERALL PERFORMANCE 30% 40% 20% 10% FINANCIAL PERSPECTIVE CUSTOMER PERSPECTIVE INTERNAL PERSPECTIVE LEARNING PERSPECTIVE 20% 30% 20% 10% 15% 5% Strategic Objective 1 Strategic Objective 2 Strategic Objective 3 Strategic Objective 4 Strategic Objective 5 Strategic Objective 6 Maintain the Transportation System Operate the Transportation System Develop the Transportation System Determine the Optimal System Design Improve Service Quality Strengthen Neighborhoods 25% 25% 50% Performance Measure 1 Performance Measure 2 Performance Measure 3 Repair Response Travel Speed High Quality Streets 15 FIGURE III Airline AHP Hierarchy OVERALL AIRLINE PERFORMANCE FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE NONFINANCIAL PERFORMANCE Capital Turnover Customer Satisfaction Complaints per 100,000 Enplanements Sales to Equity Cash Flow Fixed Asset Efficiency Aircraft Miles per Aircraft Cash Flow from Operations to Sales Cash Position Labor Efficiency Cash to Assets Aircraft Miles per Employee Financial Leverage Materials Efficiency Debt to Assets Aircraft Miles per Gallon of Fuel Return on Investment On-time Performance Return on Assets On-time Arrival % Short-term Liquidity Passenger Volume Current Ratio % of Major Airline Revenue Seat Miles 16 FIGURE IV Airline AHP Weightings OVERALL AIRLINE PERFORMANCE 60% 40% FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE NONFINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 37.5% Cash Flow Passenger Volume 34.9% 27.6% Financial Leverage Labor Efficiency 26.7% 14.7% Short-term Liquidity Fixed Asset Efficiency 16.3% 8.4% Cash Position Materials Efficiency 9.5% 6.8% Capital Turnover Customer Satisfaction 7.9% 5.0% Return on Investment On-time Performance 4.7% 17 TABLE 1 Correlations of Annual Airline Stock Returns with AHP-generated Composite Performance Scores and Competing Measures of Overall Performance (1999-2003) Airline Correlation of Annual Stock Returns over the period 1999-2003 with: AHP-Based Weighted Performance Scores Cash Flows Equal Weighting of Performance Measures Alaska 0.755* 0.037 0.686 American 0.985*** 0.455 0.934** America West 0.914** 0.411 0.898** Continental 0.881** 0.555 0.697* Delta 0.814** 0.682 0.708* Northwest 0.680 0.828** 0.453 *,**,*** Statistically significant at the 10 percent, 5 percent, and 1 percent levels (one-tailed), respectively. 18