Weaving experiences

advertisement

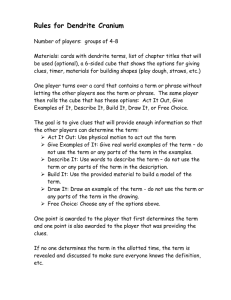

Weaving Experiences Values, Modes, Styles and Personas Alessandro Canossa IO Interactive / Danmarks Design Skole Strandboulevarden 47 2100 København Ø alessandroc@ioi.dk aca@dkds.dk understands scaffoldings as “temporary and moveable structures for building enormous new things, but also for protecting the surrounding area from the new construction. Scaffolds provide support for the workers and their tools and materials”. Translating this concept to the field of game design, I intend to expand, introduce granularity and flesh out the “scaffolding” by sub-dividing it in four phases and renaming them aptly to fit the process they are meant to describe: the facilitation of player expression within the framework of a game that is not necessarily open-ended. The four phases I suggest are: play-values, play-modes, play-styles and play-personas (see figure 1). ABSTRACT This paper proposes basic procedures and core concepts with the intent of designing single player action games that without necessitating expensive adaptive technologies allow players to express themselves. The method applied is partly inductive, leaning on empirical observations in the QA department of a game developer studio and partly deductive, deriving concepts, frameworks and core ideas from established research in user-generated content and player-enjoyment. The purpose of this research is to draft guidelines and possible pre-production pipelines for level designers in order to achieve maximum consistency in scope, production values and artistic expression, and at the same time provide a focused yet diversified players’ experience. The ideas presented here stem from a co-operation between the renowned game development studio, IO Interactive, and the design-oriented research institute, Denmark's School of Design. Fig. 1 Play-values, schemas, styles and personas The starting point in defining the scaffolding is represented by what Zimmerman calls “Play-values”: the abstract principles that the game’s design, both aesthetic and functional, should embody [13]. Keywords Gameworlds, level design, play-values, play-modes, playpersonas, player experience. These play-values will consequently inform the inception of game play modes, gestalts and schemas. Lindley individuated gestalts and schemas during his quest for interactive storytelling [6, 7]. He understands game play gestalts as patterns of interaction between player and game. He then goes on to define game play schemas as cognitive structures that underlie and facilitate the above mentioned interaction. 1. INTRODUCTION As Sanders correctly pointed out [10] all efforts aimed at engendering defined experiences are doomed to failure since experiences and emotional responses alike are too individual, subjective and rooted in people’s past to be able to scientifically aim at re-producing them. Yet today’s tendency towards mass customisation, as shown by Bozek [1] cannot be disregarded by game creators. A failure to incorporate means for mass customisation could risk alienating the large majority of people that, thanks to the developments introduced by Web 2.0 [14], are becoming more and more acquainted with the practice of expressing themselves at almost every occasion: from Myspace to Wikipedia. As a possible way out from this impasse, Sanders suggests that “Designers will transform from being designers of “stuff” (e.g., products, communication pieces, etc.) to being the builders of scaffolds for experiencing.” [11]. She Play-modes are the resulting sets of all possible navigation and interaction attitudes that players can utilise to negotiate any given situation. All the game features that motivate, facilitate and constrain player action, offer the players a certain set of methods of operation within the game. Play-styles are consistent sets of isotopic play-modes which signify, unify or distinguish players from each other. Styles need not to be consistent, implying that players can change style at a whim and select a radically different set of playmodes. If, on the other hand, a player chooses to maintain a 1 certain style, he/she will start identifying with a defined, implied play-persona. The game I chose to investigate was Kane & Lynch [5]; a team-based third person action game with strong narrative elements involving a flawed mercenary and a medicated psychopath. It is going to be released in the fourth quarter of 2007; this implies that the timing for this research is perfect in order to obtain an in-depth snapshot of the production process at all its stages. There is in fact plenty of design and concept material from the inception of the game to the final specifications. Furthermore, the game being in its final stages, means that it is almost fully playable and at the same time I have the chance to observe several review meetings first-hand. Another reason to motivate my choice is that, contrarily to other games developed at IO Interactive, Kane & Lynch is much more linear, focusing on a very strong narrative beside attempting to refresh the squad-based shooter genre. This means that if the “scaffolding” theory proves itself fruitful in this game, it will be even more relevant in less linear games. The last consideration goes to the fact that not being the game completely finalized, some of the details discussed here might be changed at the last moment before release. Play-personas are mental constructs that allow the player to identify his/her own behaviour with prototypical profiles. The logic of these play-personas is the same that governs Max Weber’s "ideal types" [12]. Personas are constructs that players build to unify their own actions and to make sense of them. It’s the player’s implied narrative tool. When a player refers his/her own adventures during a game encounter it often reads: “… and then I did this and then this happened”, etc… it is clear that this “I” is not the player him/herself but a role that he/she is playing. If players tell themselves these stories, why can’t designers plan and create games that accommodate for a (consistent) variety of them? Summarising the four-layered structure of the gamescaffolding: play-values, the first layer, inform and inspire the inception of the second layer (gestalts, schemas and modes), the second layer articulates into play-styles (third layer) and, if maintained consistently enough, they eventually coalesce as play-personas (fourth layer). It is my purpose to show how designing around play-personas allows players to express themselves, their individuality and their personality even within the boundaries of fairly linear games, hence negating the necessity of asset redundancy, multiple paths, branching or resource-intensive adaptive technology. 3. PLAY-VALUES As mentioned earlier, play-values are the abstract principles that the game design will embody. For example, the values that Zimmerman mentioned behind his SiSSYFiGHT 2000 [13] are: - reaching a broad audience; 2. PRACTICAL APPLICATION - not requiring a powerful computer to play; The initial step of the research was to investigate whether the developers at IO Interactive responsible for the game and level design were already making use of the concepts listed above, even unconsciously. Obviously the main goal was to check if these terms (or synonyms of the terms) were playing a significant role in the communication between designers, artists, programmers and level-scripters. In order to gather this kind of information, I utilised written game design documentation, direct interviews (DI), and audio recordings of internal review meetings. Armed with this data, I could make assumptions regarding the overall design of the game as a system, and on a smaller scale, to see if they influenced the functional and artistic development of the game levels. - a game that is easy to learn and play yet deep and complex; - mechanics that foster social interplay; - a smart and ironic look and setting. When confronted directly, the designers behind Kane & Lynch acknowledged immediately the term play-values, pointing out that the term used in-house was “goals” and informed me that they consciously spent time and resources defining aesthetic, narrative and functional goals for each single level but did not formalise them for the overall arc of the game experience. Nevertheless, reading the background story and the profile of the characters, I immediately recognised the overall goals lurking between the pages describing the flow of the game and the story. Secondly it was very interesting for me to try to identify the four layers of the scaffolding in a game currently under development at IOI, independently of whether the designers made conscious use of the terms or not. I reviewed material at very different stages: from the earliest game concept to the finished documentation, from first playable prototypes to the finished game with the purpose of charting the evolution of the scaffolding and its implications for the final product. The main character, Kane, is described morally as both light and dark, battle-hardened but with a strong sense of style, ruthless in fending for his life but with strong values of honour and family, physically fit but smoking too much. He has learnt not to trust anybody the hard way and now he’s been paired with a partner he strongly dislikes, Lynch, to carry out a mission that he feels is deeply wrong but is unavoidable if he wishes to save his family. It’s a character built entirely on contradictions and strong themes, right and wrong are never clearly separated and the story arcs are 2 addressed internally as “mechanics” or “features”. Reading the game design documents I discovered two distinct groups of play-modes: actions performed by the player on the game world (the avatar, the environment and other NPC) and actions performed by the player on the crew of mercenaries that follow the avatar. World play-modes are: - Walk - Run - Sprint - Crouch - Sneak - Climb - Rappel - Cover - Pick up - Context sensitive actions (plant bomb, man turret, break door) - 3rd person shooting mode - Over the shoulder shooting mode (blind fire) - Sniping - Selecting-swapping weapons - Single shot - Full auto - Throwing grenades - Variable modal accuracy - Bare hands combat - Push-blade combat - Healing never fully accomplished. This attempt to dodge more mainstream and manichean solutions results in the relatively easy task of confirming whether these values are transferred to the successive layers of the scaffolding for experiencing. The Narrative Play-Values (NPV) identified are: - NPV1: the revenge of an underdog facing overwhelming odds forced into trusting untrustworthy allies. Importance of the “fragile alliance”. - NPV2: a highly moral man cast by misfortune in a highly immoral environment, trying to do right by doing wrong. - NPV3: the main hero is a man that loves his daughter, a legendary mercenary and possibly a traitor. Functional Play-Values (FPV) are: - FPV1: action, emphasis on fighting rather than opening doors or operating equipment. - FPV2: simplicity, to support a fast paced game play and to increase the appeal to console gamers commands need to be very simple. - FPV3: creativity, players should have the freedom to creatively use tactics in varied ways to engage the enemy As expected, narrative play-values mainly informed the flow of the action and the structure of the tasks and missions of the different levels in the game, while functional play-values dictated the choices made by the designers while defining play-modes, so far confirming the hypotheses laid out in the scaffolding theory. Crew play-modes are: - Ammo request - Shoot at - Go there - Follow me - Crew member heal - Crew member select 4. PLAY- MODES, SCHEMAS AND GESTALTS As mentioned earlier play-modes are each and every one of the rules of the game, all the actions available to the player while playing a game. Play-schemas are the mental models that players utilise to understand the context and represent their actions. According to Lindley, they are “cognitive structures that link declarative (or factual) and procedural (or performative) knowledge together with other cognitive resources (such as memory, attention, perception, etc.) in patterns that facilitate the manifestation of appropriate actions” [8]. Lindley defines play-gestalts as patterns of interaction between a player and the game, they are usable subsets of all the game rules and features; they represent a possible minimum set of rules that are necessary to successfully support a particular playing style [7] and progress in the game. When presented with these concepts the designers recognized only play-modes and explained that they are Observing testers playing, talking to each other and conducting direct interviews allowed me to group these play modes in schemas, here are the individuated schemas for player actions: - Movement (walk, run, crouch, pick up) design affected by FPV2 - Action movement (climb, sneak, sprint, rappel, cover, context sensitive actions, healing, using equipment) design affected by FPV1 - Basic ranged combat (3rd person mode, single shot, selecting weapons) design affected by FPV2 - Advanced ranged combat (over the shoulder mode, full auto, throwing grenades, variable modal accuracy, sniping, swapping weapons) design affected by FPV1 - Basic close combat (bare hands) heavily influenced by both FPV1 and 2 3 - Advanced close combat (push-blade) heavily influenced by both FPV1 and 2 Crew actions schemas are: - Squad command (shoot at, go there, follow me) directly influenced by both FPV2 and 3 - Individual command (ammo request, heal, select, shoot at, go there, follow me) clearly the outcome of NPV1 and FPV3 implications for the players and for the narration are immense. When asked directly, game designers recognized immediately the concept of play-styles, they know exactly what it means and what it implies, yet they do not seem to make use of it during the design phase, it does not appear in other internal communication such as review meeting and it is not mentioned anywhere in the design documentation. Nevertheless observing game testers it was clear that it is perfectly possible to develop personal play-styles. The domain of play-styles still requires a lot of work, but the possible outcome in terms of increased player satisfaction definitely calls for further research. Schemas, in this game, are layered as “basic” and “advanced”, meaning that beginners choosing a low level of difficulty can successfully accomplish the missions making use solely of basic schemas. Once players have acquired a sufficient level of familiarity with the game, they can start experimenting with the different options they are given and eventually develop a favourite set of play-gestalts to face the various game encounters and challenges. Play-gestalts are dynamically defined every time a player selects among play-modes the actions that will guarantee his/her progress in the game, for example: - hold back the team in a covert position, - sneak and flank the enemy, - order a squad attack, - attack from covert position in “over the shoulder” mode. In order to illustrate the impact of play-styles in the playing experience we can examine the very first level of Kane & Lynch: “Bustout” (see the map of the level in fig. 2). 5. PLAY-STYLES If players chose to negotiate game encounters through consistent, isotopic play-gestalts, they start expressing a peculiar play-style. In real life the variations available to execute a task or tell a story are nearly countless as shown for example by Queneau in “Zazie dans le metro” [9]. On the other hand in the game environment, even accounting for the phenomenon of “emergence”, the possible interactions are much more limited because game designers only include very small subsets of all the possible actions. Chomsky acknowledged the importance of “infinite use of finite means” in his works on generative grammar [2] and it shows how the expressive potential of the limited input is vital to gain a glimpse in the player’s state of mind. It is possible then to read each action started by the player in the game environment as the semiotic “unintentional sign” defined by Eco: “actions of an emitter, perceived by a receiver as signifying artefacts” [3]. Due to the connotative layer, these signifying artefacts may unconsciously reveal properties of the mental state and behaviour of the emitter. It pays off to understand player’s actions as semiotics acts (unintentional signs) because play-styles point towards more than just strategies to successfully complete the game. For example the functional attributes of “bare handed close combat” (basic schema) and “armed close combat” (advanced schema) are nearly identical, but the psychic Fig. 2 map of level “Bustout” In this initial level the player starts at the location denominated “Crash”, professional mercenaries ram the prison transportation that was taking Kane to his execution. It is a very emotional experience thanks to a clever use of camera and video-post effects (wavy cam, unclear and hazy vision, bloom and blur effects), although this necessitates for an extremely linear progression where the player does not really have any choice and is “on rails”. The player is 4 forced to escape the first shootout without a chance to fend for him/herself, the only refuge is in the alley. The sole choice given until the mark “police car” is the chance to pick up a handgun, which in turn is a way to train the player to pick up objects. We arrive at the second shootout with the possibility to just observe our “saviors” or to take part in the action either with unarmed close combat or with the handgun. After climbing the fence (another play-mode learnt from the “advanced movement” schema) the player gains access to rifles dropped by mercenaries shot by the helicopter that appears in the back lot of the garage. In the garage, which marks the end of the first half of the level, we have the first really big confrontation where the player will have to hold a small army of policemen until a gas tank explodes liberating the way to the fourth shootout. This area can be quickly evaded just by running in the alley where the player learns another way or negotiating obstacles: by jumping over a car it is in fact possible to gain access to the warehouse, the first real breathing room since the beginning. In the lower part of the warehouse another shootout forces the player out and towards a diner, stage for the last gunfight before the escape of the crew. - Studying these variables is the main instrument in order to detect coalescing play-styles. 6. PLAY-PERSONAS When a player behaves consistently in the game and maintains a defined play-style for longer periods (if not for the whole game altogether) then he/she identifies completely with a certain profile. I am going to call these consistent profiles “playing personas”. In spite of the fact that players tend to switch styles extremely easily, it’s clear that the designers themselves acknowledge the possibility to play out personas. For example in the game “Hitman: Blood Money” [4] players are given special rewards for completing missions following certain set rules (only killing the assigned targets and getting out with the suit). Those rules restrain the in-game behaviour to a specific style that maintained long enough gives birth to the play-persona called “Silent Assassin”. Play-personas are constructs that share many similarities with Weber’s ideal types. This first level does not allow for crew control and it consists mostly of narrow, corridor-like passages, yet the linearity is concealed with several open areas and a couple of obstacles to overcome in order to proceed along the path. In spite of the limited set of options available to the player and the narrow, linear structure, it is very successful in establishing and reinforcing both narrative and functional play values, furthermore player expression in terms of play style is not only allowed, but deliberately encouraged in many of the shootout sections. “An ideal type is formed by the one-sided accentuation of one or more points of view and by the synthesis of a great many diffuse, discrete, more or less present and occasionally absent concrete individual phenomena, which are arranged according to those one-sidedly emphasized viewpoints into a unified analytical construct”. [12]. For Weber the ideal type is a conceptually pure mental construct used to monitor the behaviour of social groups. It is totally theoretic, almost fictitious and generally not empirically found anywhere in reality, but in our case it can prove to be a priceless tool to measure play-behaviours. Ideal types are used as some sort of unit of measure, standards much like "metre", "second" or "kilogram" not really found in nature, but useful to measure it. Navigation and interaction attitudes are important looking glasses through which we can study emerging play-styles. Navigation attitudes tell us how players move in the game space: - physical position of the avatar within the limits of the available space in relation to the vector of hostile NPCs. - pace of movement (walking, running, staying still, sneaking, sprinting, etc.) - use of cover, flanking or frontal charges. Ultimately are those mental models that players refer to when they report “I totally pulled a Rambo there to pass through the blockade” and it is up to the designers to plan and provide diverse, engaging, satisfactory and at the same time consistent play-personas. Interaction attitudes inform us on how players choose to negotiate obstacles and NPC: - preferred weapon - preferred shooting mode - use of grenades - use of advanced teamwork (swap weapon, give ammo, heal, etc.) - use of individual command or squad command whether or not player makes use of aiming modifiers 7. CONCLUSIONS Each one of the four stages of the “scaffolding for experiencing” can lead to increased player satisfaction and more focused and consistent design. Although the designers were almost always aware of the concepts and cognizant of their meaning, they were only occasionally found in the documentation or utilised in internal communications. Nevertheless their existence and relevance has been proven during direct interviews with testers. 5 Clear improvement can be gained just by becoming aware of mechanisms that already are present in the back of the mind of the designers, artists and scripters. d2.1: working model of computer game experience. 30.09.2006. [9] Queneau, R. Zazie dans le metro, Paris, Gallimard,1972. 8. REFERENCES [10] Sanders, E. B.-N. “Scaffolds For Building Everyday Creativity” in Design for Effective Communications: Creating Contexts (Ed.) Allworth Press, New York, 2006. As found on: http://www.maketools.com/pdfs/ScaffoldsforBuildingE verydayCreativity_Sanders_06.pdf [1] Bozec, P. "My Everything" - From Play Lists to Profiles and Virtual Worlds. Mass Customization: The Explosion of Choice and Creativity, keynote at Nordic Game, Malmo, 2007. [2] Chomsky, N. Le strutture della sintassi, Bari, Laterza, [11] Sanders, E. B.-N. Scaffolds for Experiencing in the 1970. New Design Space in Information Design Institute for Information Design Japan (Editors), IID.J, GraphicSha Publishing Co., Ltd., 2002. As found on: http://www.maketools.com/pdfs/ScaffoldsforExperienc ing_Sanders_03.pdf [3] Eco, U. Trattato di semiotica generale, Bompiani, Milano, 2002. [4] IO Interactive. (2006). Hitman: Blood Money. [XBOX 360], Eidos. [12] Weber, M. The Methodology of the Social Sciences. [5] IO Interactive. (2007). Kane and Lynch. [XBOX 360], Edward Shils and Henry Finch (eds.). New York: Free Press. 1949. Eidos [6] Lindley C. A. and Sennersten C. “A Cognitive [13] Zimmerman, E. “Play as Research: The Iterative Framework for the Analysis of Game Play: Tasks, Schemas and Attention Theory”, Workshop on the Cognitive Science of Games and Game Play, The 28th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Vancouver, Canada, 2006. Design Process” in Design Research: Methods and Perspectives edited by Laurel, B. and Lunefeld, P. Final Draft: July 8, 2003. As found on: http://www.ericzimmerman.com/texts/Iterative_Design. htm [7] Lindley C. A. The Gameplay Gestalt, Narrative, and [14] As found on: Interactive Storytelling Published in the Proceedings of Computer Games and Digital Cultures Conference, June 6-8, Tampere, Finland, 2002. http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005 /09/30/what-is-web-20.html [8] Lindley, C. in FUGA The fun of gaming: Measuring the human experience of media enjoyment - deliverable 6