MS Word 181k - New Zealand Council of Trade Unions

advertisement

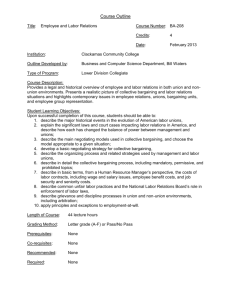

Submission of the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions to the Transport and Industrial Relations Committee on the Employment Relations Law Reform Bill 27 February 2004 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. The CTU welcomes the introduction of the Employment Relations Law Reform Bill. We believe it is a modest improvement to a moderate law. 2. The CTU submits that there has been a very significant legacy due to the anti-worker Employment Contracts Act. The Employment Relations Act established a set of principles and objectives that are both fairer and more appropriate to a modern economy. But the detail of the Employment Relations Act did not match the objectives. 3. Even if all our submissions are accepted, the amended Employment Relations Act will be more similar to the Employment Contracts Act than either the Industrial Relations Act 1973 or the Labour Relations Act 1987. 4. Unions are arguing for sustainable workplaces in the context of sustainable businesses. This will occur if the emphasis shifts towards valuing staff, recognising their contribution, investing in skill development, better use of technology, and a recognition that quality employment and productivity outcomes emerge from a decent work environment. 5. Promotion of collective bargaining is in line with fundamental international minimum standards binding New Zealand and its international counterparts (as set out in the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (1998)). NZ has recently ratified ILO Convention 98. 1 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 6. 2 This CTU submission supports the tenor and direction of this Bill, but we also suggest a number of areas where improvements are required. 7. The CTU has set out a detailed technical submission in Appendix 1 and a detailed proposal on Equal Pay in Appendix 2. 2 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 3 1. Introduction 1.1 The New Zealand Council of Trade Unions (CTU) is the internationally recognised central trade union organisation in New Zealand. It represents 34 affiliated unions with a membership of approximately 300,000. Of the total union members in New Zealand, 88% belong to unions affiliated to the CTU. 1.2 The CTU welcomes the Employment Relations Law Reform Bill (“the Bill”). We note that the Bill implements policy clearly stated in the Labour policy statements at the time of the 2002 general election. The Bill addresses some key concerns about the effectiveness of the Employment Relations Act (”the Act”) in meeting its objectives. The Bill follows a review conducted over a period of about twelve months. 1.3 However, the CTU is concerned that the Bill does not adequately address a number of key issues. 1.4 This submission is in three main parts. First of all we comment in Sections 2-7 on general issues relating to the Bill. The second part of our submission is a detailed technical analysis containing recommendations that we are asking the Select Committee to consider. The third part is our detailed submission on equal pay issues. An outline of our submission is as follows: Section 2 Background (page 3) Section 3 Evaluation of the Employment Relations Act (page 13) Section 4 Equal Pay Summary (page 25) Section 5 Employment Relations and Economic Performance (page 28) Section 6 Key Provisions of the Bill (page 34) Section 7 Summary (page 37) Appendix 1 Technical Submissions (page 39) Appendix 2 Equal Pay (page 70). 3 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 4 2. Background 2.1 The introduction of the Employment Relations Act was a highly significant measure. For the CTU it was the culmination of nearly a decade of opposition to the Employment Contracts Act. Unions saw the Employment Contracts Act as hostile to workers, to unions, and to collective employment relationships. It encouraged individual contracts in the sure knowledge that the ILO recognises the vital importance of collective bargaining to deliver fair outcomes for workers. It allowed “take it or leave it” bargaining. It abolished industry and occupational awards. 2.2 We were not alone in describing the Employment Contracts Act as a significant change. The Auckland District Law Society notes that: When the Employment Contracts Acts 1991 became law in 1991 it significantly altered the way in which employment law historically operated in New Zealand. The National Government, which was voted into power in 1990, took economic reform of the market place to a new level with the passing of the Employment Contracts Act 1991. 1 2.3 The CTU had catalogued the effects of the Employment Contracts Act – on workers’ pay and conditions and on the economy. We therefore supported the new Employment Relations Act even though a fair number of our submissions did not get included in the Act. As the CTU said at the time, it is a modest law. It has now been shown to be far too modest. This is not necessarily a criticism of the government or of the union stance at the time. There was a desire for a modern new 1 Auckland District Law Society http://www.adls.org.nz/lawnz/lawnz3/lawnz14.asp 4 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 5 law, and one which was built on ILO Conventions 87 & 98. Unions thought that this was a foundation for an enduring law – one that could largely survive political changes. But the effect of decisions by the Court of Appeal, and the actions of hostile employers, were underestimated. 2.4 Even if all our submissions on this Bill are accepted, the amended Employment Relations Act will be more similar to the Employment Contracts Act than either the Industrial Relations Act 1973 or the Labour Relations Act 1987. 2.5 In our submissions on the Employment Relations Act, we noted our concern for vulnerable workers. We said that: “The ECA has been at its most unfair in the effect on the treatment of vulnerable employees. Employees can be “vulnerable” for a number of reasons ………a modern employment relations law should recognise and understand the problems faced by vulnerable employees”. There was a strong requirement for the new law to construct a fair set of arrangements to ensure that vulnerable workers could have genuine access to collective bargaining and other employment rights. 2.6 However, to replace decades of industrial relations laws built on awards, arbitration, and unqualified preference with a law based on objectives of good faith and the promotion of collective bargaining, was always going to be something of an unknown journey. It was unclear if this would be an adequate mechanism to protect worker rights and in particular the problems faced by vulnerable workers. In 2000 the key contrasts were between the fundamentally anti-union, individualist and contractualist Employment Contracts Act, and a new law based on 5 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 6 good faith relationships and the ILO conventions. In the event, the new Act has made only modest advances. 2.7 This was recognised by many observers. For instance, “The Employer" February 2000 issue included a commentary by the EMA (Northern) (the largest regional employer group) which acknowledged that: "Although undoubtedly a step backward, Labour's policies are not a return to the past … the ERA [the Government's employment relations act] prescription for unions bears little relationship to the pre-1991 regime…” 2.8 A prominent lawyer2 noted that: “An objective, rational analysis of the ERA shows that the descriptions of it as being radical pro-union legislation were misguided.” He referred to the comments of Professor Dennis Nolan, an internationally respected American labour law scholar, who stated that: “Viewed in international perspective, then, the ERA is entirely normal and even expected. If anything, it follows Pencavel’s prescriptions for productive collective bargaining systems more closely than do the current laws of New Zealand’s major trading partners. In comparison with almost any of those systems, New Zealand still has a remarkably free labour market and a remarkably unregulated system of labour relations”. 2.9 Roger Kerr3 of the New Zealand Business Roundtable observed: Peter Churchman NZ Law Society Conference 2001 “Employment Relations Act 12 months on.” 2 6 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 7 “the ERA did not return New Zealand to compulsory unionism, compulsory arbitration and national awards (despite a hankering in some quarters for multi-employer contracts). Like the ECA it is primarily an enterprise-focused regime. Therefore – and having regard to other changes such as the opening up of the economy and changes in management practice – no one should have expected radical changes in behaviour, at least in the short term. 2.10 In fact, the new law was modelled closely on core conventions of the International Labour Organisation (ILO). New Zealand was a founding member of the ILO in 1919. As a member it is bound by the ILO Constitution and the Declaration of Philadelphia to comply with the principles of freedom of association, the right to organise and the promotion of collective bargaining. These are contained in conventions 87 and 98. In 1998, New Zealand was part of the international labour conference, which unanimously adopted the Declaration of Fundamental Principles. These principles include conventions 87 and 98. They are internationally recognised as core standards and fundamental human rights. We note that Convention 87 on freedom of association and the right to organise was developed in 1948 in conjunction with United Nation’s development of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations and is of equal status. Kerr, R. “Assessing the Employment Relations Act”, Work Relations NZ Conference19 November 2001. 3 7 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 2.11 8 The United Nations4 has since signalled its approval of the new law. In May 2003, it noted that: The Committee (Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights) welcomes the Employment Relations Act of 2000 which facilitates collective bargaining, strengthens the role of trade unions and introduces measures of protection against harassment and discrimination in the workplace. 2.12 The Employment Relations Act is therefore recognised as a moderate law in keeping with the mainstream of international trends and guidelines on employment law. 2.13 Nevertheless, when the Act was introduced three years ago employer organisations predicted dire consequences for the economy and employment growth. In fact unemployment fell, employment grew strongly, economic growth improved significantly, and household incomes increased. 2.14 Unemployment is 4.6%. In 1999 before the ERA came in it was 7.5%. 2.15 The latest GDP figure shows 3.9% growth for the September 2003 year. In the three years prior to the ERA, growth averaged 1.9% a year. In the last 3 years, it has averaged 3.6%. 2.16 How are businesses doing? Tax data suggest that profit levels are up, and the level of business failure is well down. For instance the rate of bankruptcy and liquidation is much lower than in the 1990s. The OECD5 has recently noted that one of the factors contributing to favourable government revenue has been “greater than budgeted 4 United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Thirtieth Session, 5 - 23 May 2003 E/C.12/1/Add.88. 8 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 9 increases in …..corporate tax (reflecting the strength in company profits)”. 2.17 But the labour market is still affected by the Employment Contracts Act period. Unions are also saying that just as there is a long and damaging legacy from the privatisation programme, the excessive deregulation in the state sector and the economy generally, the underinvestment in skills, the failure to invest in modern infrastructure and so forth, there is also a long legacy from the Employment Contracts Act. 2.18 The labour market of today bears a close resemblance to that of the 1990s in some respects. It is true that unemployment is down and investment in skills is up and these are hugely important. Unions recognise that the government has genuinely delivered across a whole range of employment policies. We've seen modern apprenticeships, more funding for industry training, regular increases in the minimum wage, paid parental leave, health and safety changes. 2.19 But collective bargaining which can deliver wage increases and improved conditions for large groups of workers, a shift which is necessary on an industry basis in some industries such as road transport, is being constrained by an inadequate law and sustained employer resistance reminiscent of the 1990s. 2.20 In 1989 – 90 the last bargaining round before the ECA 701,574 workers or 48% of the workforce were covered by collective agreements or Awards. Ten years later in the 1998 – 99 year, only 421,400 workers or 24% of the workforce were covered by collective employment contracts. 5 OECD (2004). Economic Surveys : New Zealand, Volume 2003, Supplement No. 3 – 9 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 10 2.21 The scale of labour market deregulation we experienced in the 1990s is very difficult to reverse. Employers have many options (including casuals and fixed-term contracts) to avoid minimal re-regulation. The removal of awards and arbitration has meant that many issues that would normally be pursued through collective bargaining spill over into minimum code issues across the whole economy. And unions get bogged down in enterprise bargaining with high transaction costs and low density. 2.22 Hopefully, some employers are now starting to recognise the damage created by their employment and market practices. An example of the legacy of underinvestment in training and low rates of pay can be seen in the transport sector. It is estimated that there will be a shortage of 4000 drivers by 2005 and 10,000 by 2010 if current recruitment trends continue. Pay, conditions, and pressures on drivers were highlighted as key factors (Dominion Post, 21 April 2003). 2.23 But this very underinvestment in skill development alongside major labour shortages is part of the context that has resulted in unions arguing for such rights as longer paid parental leave, better work-life balance and the flexibility of working arrangements that suit workers rather than just employers. The CTU campaign on work-life balance is at the core of these issues. 2.24 The CTU believes that the labour market is dysfunctional because there are industry problems that require industry solutions. The labour market is disaggregated into small enterprise bargaining units. Enterprises need to be competitive within industries – but if they adopt a lowest common denominator approach as in the trucking sector, the results can be disastrous. January 2004. Page 146. 10 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 11 2.25 How many more industries have to reach a crisis point before employers look at sustainable options – such as industry minimum standards, multi-employer agreements, industry-wide investment in skills, partnership with unions and so forth? 2.26 Of course, it is never fair to generalise. Some employers continued to deal with unions in good faith throughout the 1990s and do so now. Some have adapted to the new legislation. But many have not. 2.27 Employer organisations opposing this Bill no doubt preferred the Employment Contacts Act. There are many experiences under that legislation. For example, one union member who wrote to the Labour Department about her experience said that: “As soon as the Employment Contracts Act came in everything changed in this place. We were told – now he’d do it his way. First he got rid of the union, and some were threatened that if they belonged to the union they would be down the road. The contracts were never negotiated. We were called in one by one and given this printed document with a place to put your signature. Some of the young ones were not allowed to take their contracts home for their parents to read. The first year all of us who already worked there got penal rates. As people left or were sacked, the new ones went on to a flat rate with no set amount – they were all getting different wages. Within a year there was a 90% rollover of staff.” 2.28 This is of course the employment relations environment that critics of this Bill would like to see back again – where the employer can impose pay, terms and conditions without negotiation or good faith considerations. 11 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 12 2.29 The Employment Relations Act marked a turning point. While it did not return to legislation that provided for “compulsory” union membership, industrial awards, or arbitration, it rejected the ECA model. Based on good faith, and an objective of promoting collective bargaining, the Act was different to what had been seen before in New Zealand. It was always going to need to be reviewed at an early stage. 2.30 The CTU was pleased therefore to note the intention of the Labour Party to support a review. On 4th July 2002, some 20 months ago, Labour announced that it would: “review the operation of the ERA to identify if any fine-tuning is needed either in the law, or in administrative supports that operate to implement the law. The review will focus on giving effect to the aim of promoting, as opposed to simply permitting, the free association of workers and collective bargaining. Matters that will be covered in the review include: Whether more administrative support needs to be given to facilitate multiemployer collective bargaining, particularly where the size of employer units in particular sectors makes enterprise bargaining inefficient and ineffective. The adequacy of provisions in the ERA to discourage and prevent the undermining and avoidance of collective bargaining. Provisions allowing union fee deductions for union members not covered by a collective agreement. Improving monitoring and research into labour market practices. Whether compliance costs associated with the bargaining process can be reduced. Processes for accessing employment relations education leave (EREL), and the provision of EREL for union members not covered by collective agreements. The extent to which the intent of the Act and, in particular, the principles of good faith bargaining are given sufficient weight in the application of the Act. Whether the provisions of the Employment Relations Act are consistent with ILO conventions 87 and 98 so as to enable ratification”. 12 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 2.31 13 Government intentions to review the ERA were well reported in 2002. 6 There is no basis for sections of the business community to suggest that any element of the Bill came as a surprise. The timetable for submissions over the Xmas period is a month longer than that for the very radical changes when the Employment Contracts Act was rushed into law in 1990/91. 3. Evaluation of the Employment Relations Act 2000 3.1 The prime objectives of the Employment Relations Act include the promotion of collective bargaining and good faith relationships. Let’s look at the labour market reality and test it against those objectives. In August 2002, the Department of Labour reported to the Government that only 15 percent of workers are covered by collective agreements. It has fallen to 12% in the private sector. Many unions are engaged in repetitive enterprise bargaining. The incidence of multi-employer bargaining resulting in actual settlements has been minimal. And employers have found that good faith is more like a wet bus ticket and does not create a real disincentive to bypass unions and undermine collective bargaining. 3.2 Some of the comments that the ILO made about the Employment Contracts Act can be used also as a benchmark to evaluate the current law. The ILO Committee on Freedom of Association found that the lack of support for collective bargaining in the ECA was incompatible with ILO principles: 255 As regards employment contracts, the Committee finds it difficult to reconcile the equal status given in the Act to individual and collective contracts with the ILO principles on collective bargaining according to which the full 6 For instance, Colin James in the Business Herald, 29 July 2002 13 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 14 development and utilisation of machinery for voluntary negotiations between employers or employers’ organisations should be encouraged and promoted, with a view to the regulation of terms and conditions of employment by means of collective agreements. In effect, it seems that the Act allows collective bargaining rather than promoting and encouraging it.7 3.3 The ILO added that to comply with international principles the new Bill must not only allow collective bargaining to occur, it must promote and encourage the regulation of terms and conditions of employment by collective agreements. They said that to achieve this: (1) The collective bargaining mechanisms must be clear and easy to operate so that they do not restrict the right of representative unions to bargain. (2) The provisions on the relationship between collective and individual employment contracts must reflect the overall principle that collective bargaining should be promoted. (3) The provisions on good faith must reflect the overall principle that collective bargaining should be promoted. The CTU submits that although the Employment Contracts Act comprehensively failed to meet these requirements, the Employment Relations Act also falls short of the international minimum labour standards laid down in the ILO conventions and jurisprudence. 3.4 The means by which the ERA promotes collective bargaining is tenuous to say the least. There are no awards. Unions are allowed to 7 Committee on Freedom of Association, 295th Report Case No. 1698, emphasis in original. 14 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 15 negotiate collective agreements. Unions are by definition “collective organisations”. But any group of people can form a union. There are now 183 unions, a significant increase from the 82 unions at the end of 1999. Strikes are permitted in a multi-employer bargaining situation but there are limited obligations on employers to bargain in any genuine sense in response to a union initiated multi-employer negotiation. 3.5 The latest review of union membership and collective bargaining8 noted that: “The individualisation of the employment relationship under the ECA remains thus far unchallenged by the ERA. Less than one quarter of New Zealand workers are employed under the provisions of a collective agreement, although an unknown number have their pay and conditions determined by an agreement negotiated collectively. Where collective bargaining does occur it is more likely to be workplace based rather than industry based, leaving many unions, especially in the private sector locked into an inefficient site-by-site bargaining mode.” 3.6 As Harbridge and Thickett”9 observe: “Multi-employer bargaining, something supported but not actively promoted by the Employment Relations Act, has experienced little growth”. 3.7 Peter Churchman10 has observed that: 8 Unions and Union Membership in New Zealand: Annual Review for 2002 Robyn May, Pat Walsh, Raymond Harbridge & Glen Thickett. 9 Harbridge, R. and Thickett, G. “Unions in New Zealand : A Retrospective”, AIRAANZ Conference, 4-7 February, 2003, Melbourne. 10 Peter Churchman NZ Law Society Conference 2001 “Employment Relations Act 12 months on.” 15 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 16 “obtaining a MECA is not going to be easy and, under the ERA, we are unlikely to see a return to the industrial landscape that prevailed before 1991”. 3.8 In one Auckland rest home, the union has been to mediation 20 times, but the employer still refuses to negotiate a collective agreement. Over 100 workers at a bank want to go on to a collective agreement like other union members. But their employer insists they remain on individual agreements. Another rest home employer has been giving wage increases to non-union staff and has said it will not give the same increases to those seeking a collective agreement. 3.9 We set out more detailed cases below: (a) For three years a group of initially 241 workers (now under 100 because of turnover and pressure to remove themselves from the bargaining unit) at a major bank have been trying to negotiate an extended coverage clause to an existing collective agreement. They provide services such as lending and investment advice for customers. The bank says they have to be on individual agreements even though they are not in management positions and their employment situation is the same as tellers who are covered by a collective. Perry, formerly an investment advisor, says the bank argues it is not convinced that a collective agreement is the best option for these workers, who are members of Finsec, and that it prefers an individual relationship with them. “Last year in frustration we tabled our individual contracts, which are the same, and said ‘there you go, they are the basis for our collective’ and they still refused to agree to our claim,” Perry says. He says the issue has been to mediation four times. “The fact is that having us on individual agreements enables the bank to change our conditions of work unilaterally and we are powerless to do anything about it,” says Perry. “For example, at one stage we were told we had to sell insurance cover the bank was offering. The staff that refused were managed out of the company, or decided to leave.” Perry says the bank re-designates positions covered by the collective agreement into “specialists” (specialists such as Legal and HR roles are excluded from coverage) and then offers the incumbents individual agreements on much inferior terms. People who refuse to sign the individual agreements are made redundant and new staff members who are recruited into these positions are not told about the union. “This is crippling union membership,” Perry says. “The bank is confounding the spirit and intent of the Employment Relations Act.” 16 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 17 (b) Blair works at a Christchurch engineering firm, where he is also a delegate for the Engineering, Printing and Manufacturing Union. He says the company engaged an outside consultant to assist in the process of challenging and fragmenting the workforce. As a result, the company removed itself from the EPMU multi-employer collective agreement (MECA), which it had been a part of for more than 10 years, in favour of an enterprise agreement. “The next step was to start undermining the collective agreement by offering more money to workers to sign up on individual contracts,” says Blair. “The union saw this as a lack of good faith on the part of the company.” It took eight months for the collective agreement to be settled, and Blair says the company undermined the union all through the process. There are around 80 workers – half of them were in the union but that number has dropped significantly in the past year. “The drop in membership means less power for collective bargaining,” Blair says. Union members haven’t lost any conditions yet and got a three per cent pay rise in line with the MECA, “but we could lose it all if the union is decimated here”. “To further undermine the union collective, the employer has set up a non-union ‘collective’ of workers on individual contracts,” Blair says. “They hold meetings and elect representatives. Its members have all the rights and conditions that union members have.” Blair says the employment law needs to be strengthened “so that employers can’t undermine collective bargaining - which is the only way workers have any power”. (c) Susan, a registered nurse and member of New Zealand Nurses Organisation, says it took more than a year to negotiate a collective agreement to cover three aged care facilities in the North Island because the company opposed a multi-site collective and, for a long time, simply refused to talk. When an agreement was finally reached Susan, who worked at one of the homes, says the company immediately began to undermine it by paying non-union staff more than those covered by the collective contract. The New Zealand Nurses Organisation and the Service and Food Workers Union initiated bargaining in April 2002. It took two months before the company agreed to sit down and talk to the unions. No further talks were held for the rest of 2002 because the company kept postponing or canceling sessions. The company did not respond to claims tabled, as it is required to do under the Employment Relations Act. The company refused to negotiate a multi-site collective insisting it would only negotiate agreements for each worksite. In line with the Code of Good Faith the unions put aside the issue of a multi-site collective and asked the company to respond to its other claims. The company refused to do so unless its demand for separate worksite agreements was met. Workers took industrial action. Nurses, kitchen and laundry staff at all three rest homes went on strike for two days. A multi-site collective agreement was finally signed settled in May 2003, 13 months after bargaining was initiated. The workers received a two per cent pay increase. Shortly after the union members received the two per cent rise, non-union staff received a letter from the employer. It said as a reward for their efforts they would receive a three per cent pay rise. There were no negotiations with the non-union staff, 17 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 18 the company simply gave them the rise which was based on the settlement negotiated by the unions. New employees are given a strong message from their managers that they don’t need to join the NZNO or the SWFU to receive any pay increases they negotiate. Susan believes the company is trying to undermine the collective agreement and the unions. Susan says the unhappy situation at the work place had a direct impact on the residents. A rotating roster was imposed on staff which had a huge impact on their family life and childcare arrangements. When she raised it with the manager she was told “if they don’t like it they can go down the road”. The wage rise for the non-union staff “disgusted” her and she felt discriminated against as a union member. Susan says staff have to fight for their rights and there is a culture of intimidation by the manager. When she said she would write to her MP about the situation at work, she was threatened with the sack. Caregivers at her former place of work, she says, are “slaving away for $10 an hour”. (d) In December 2001, workers at three Wellington rest homes told their employer they wanted to be covered by a collective employment agreement rather than each worker having an individual agreement. More than two years later they still don’t have a collective agreement even though a key objective of the Employment Relations Act is to promote collective bargaining. The company is one of the largest retirement village operators in New Zealand. In the 2003 financial year it recorded an after-tax profit of $15.3 million, a 38 per cent increase on the previous year. Yet its average pay rise for that year was closer to 2 per cent. By December 2001 the Service and Food Workers Union and New Zealand Nurses Organisation had more than 120 members working as caregivers, cooks, kitchen hands, cleaners and nurses at the three rest homes. Two union delegates, Tania and Louana, say these workers wanted to be covered by a collective agreement so they could bargain with the management on a more even footing. As the company operates a secret performance appraisal system staff had no capacity to reconcile their own performance with a system that was ultimately based on corporate profitability rather than individual delivery. The company responded by arguing it wanted keep the workers on individual agreements and since then has done everything it can to frustrate their claim for a collective. The company hired consultants and engaged a law firm to argue that it was not the workers’ employer, claiming they were employed by each individual rest home. In June 2002 the SFWU filed papers with the Employment Relations Authority claiming the company was acting in breach of the good faith provisions of the ERA by failing to negotiate a collective agreement and harassing staff who were union members. The company filed counterclaims threatening to sue the union for issuing media statements that told the public what the company was doing. 18 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 19 In September 2002 the employer began giving pay rises to it non-union staff at the rest homes. In December the company wrote to the union members telling them they would also get an increase if they agreed to give up their campaign for a collective agreement. Tania has worked as a caregiver at one of the rest homes for more than three years. She says there was huge pressure on the union members to give up their claim for a collective. When she was told she would get a pay rise if she quit the union, she quit, got her increase, then rejoined the union and became a delegate. Tania says most of the workers who left the union are too scared to rejoin. Louana has been a caregiver at another rest home for more than two years. She is a delegate and, when asked to quit the union, she refused. During this time union members petitioned and tried to engage their employer. When that failed they took limited strike action. The company responded by giving $50 gift vouchers to all staff who worked during the strike. Not until the first quarter of 2003 did the company gave the union members the same pay increases it had given its non-union staff. But it has still refused the collective. After more than two years of bargaining not a single word has been agreed. (e) Like many workers, Martin, a printer for a medium-sized publishing house, hopes the Employment Relations Law Reform Bill will stop non-unionists “freeloading” on their union colleagues. More than half of the 50-strong workforce were union members when the Engineering, Printing and Manufacturing Union started negotiating a collective agreement in 2002. But the company was hostile to a collective agreement, and began an active campaign to dissuade workers from union membership, saying there was no need to be a member because any benefits negotiated with the union would be passed on to non-union staff. This badly weakened the union position, Martin says. “This lead to some members resigning from the union, while others felt there was no point in joining.” After a difficult negotiation, during which union members were pushed to the brink of industrial action, a deal was settled. The pay rise and improved conditions it delivered were passed on to non-union members. For some it was their first raise in six years. Martin says the actions of the employer completely undermined the collective as many workers left the union. There are now around six union members left – so bargaining strength has been decimated. “We feel strongly that the company did not negotiate in good faith and our future negotiations will be jeopardised.” Martin does not want a return to compulsory unionism, but says that workers who gain the benefits of collective bargaining should contribute to the process. Martin says the ERA must be amended so that employers can not undermine collective bargaining as a way of reducing workers’ ability to negotiate a fair pay deal. (f) In October 2002, 18 caregivers at a Wellington rest home were told they were about to lose their jobs. The company had been forced to shift premises, and used 19 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 20 the move as an opportunity to tear up the workers’ collective agreement and employ them on inferior wages and conditions. The company which ran the hospital had known for 19 months that it would have to shut down, but the workers were given less than one month’s notice of closure. They were told their jobs would go but they could apply for new jobs at another rest home nearby, which was run by the same parent company. The residents were simply moved from one rest home to the other. The Service and Food Workers Union asked why couldn’t the workers be transferred as well? They were told the workers were going to a new employer so they would have to apply for the jobs, be interviewed, and then wait to see if they were hired. This is despite the fact that the same parent company owned the two companies that ran the rest homes and one of the parent company’s employees managed both rest homes. Of all the workers who applied for jobs at the second rest home only two were not offered a position. These were caregivers and the two SFWU delegates – Rita and Marietta - who were not even offered casual work despite the fact they had worked for 10 years at the rest home. Both were highly qualified, having completed the National Rest Home Certificate, and the Dementia Care Certificate. Their story is representative of thousands of employees who have no protection when their work is transferred in any way. Workers in this situation usually have to reapply for their jobs and if they are taken back on it is often with fewer hours and less pay, but the same work load. Workers with a background of union activity are particularly vulnerable to victimisation. These workers are usually low-paid, so it’s impossible to save for tough times ahead. There is no legal requirement for redundancy compensation. The workers who were hired at the new hospital lost their collective agreement and were placed on individual agreements whether they liked it or not. They were paid less because they were employed for fewer hours. They also lost their weekend allowance. “Those workers are doing the same job for the same employer – and looking after the same people, yet they have had their wages cut and lost their collective agreement just because they are in a different hospital,” says Marietta. “The bosses had plenty of time to plan it all ahead, but didn’t tell us until the last minute. It’s like their workers were their least important consideration.” (g) Sina is a Wellington cleaner and her employment situation is representative of thousands of low-paid workers who have no protection when their work is contracted out, or the company they work for loses its contract to provide services. Her story is a good example of why legislative protection is needed for vulnerable workers. She cleans for two different companies, working six nights a week. Most nights she cleans for nine and half hours in total. She is paid $10.15 an hour. Every year or two, Sina faces uncertainty because her employers could lose the contracts they have to provide cleaning services. Even if she is employed by a new contractor, her hours of work or her terms and conditions could be reduced. If she wants the job, she will simply have to accept what is offered. 20 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 21 The year before last, Sina’s husband died in a house fire. During the day, she cares for her grandchildren who live at home with her. Sina has a dependent child and five grandchildren, two of whom are pre-schoolers. One of the main reasons she works as a cleaner during the night is to care for her grandchildren and to enable her own children to gain an education and to work themselves. Sina has worked at one place for a number of years, and has been employed there in the last five years by three different companies. For just over a year she has worked in a second job because her hours of work in her first job dropped from eight to six a night when a new company won the contract. It was a condition of the new offer of employment that workers accept this drop in hours. “We had to take it or leave it,” Sina says. When the contract changed over, the workers were only given a couple of week’s notice of termination. They all had to apply for their jobs again with the new company. There was great uncertainty about who would and wouldn’t get a job. For Sina, it was especially stressful because she was a union delegate. As there is no law stopping discrimination against prospective employees by reason of their union activities, Sina was particularly vulnerable. She had been dismissed unfairly (and later reinstated) before because of being a union delegate for the Service and Food Workers Union. The workers spent several anxious weeks not knowing what was going to happen to their jobs. “We all work in the night and mostly try to sleep during the day or look after kids, so it’s hard to look for other jobs,” she says. “Everyone was worried about how they were going to feed their children, and Christmas was coming up, too.” The workers did not find out whether they had a job with the new company until December 21. In addition, the employer said it did not want to employ the workers until mid-January, so they lost several weeks of work over the intervening period. For any cleaners that did not get employed, there was no redundancy compensation in the agreement, so no financial cushion. This situation remains the same today. Many “user enterprises” (i.e. those enterprises that contract out the cleaning) do not want to have anything to do with protecting the workers’ job security or conditions of work. They say that it has nothing to do with them and will not insert a provision in the tender documents requiring all workers be employed on existing conditions by the incoming contract company. Sina’s terms and conditions are contained in a multi-employer collective employment agreement. Not all commercial cleaning companies are covered by this multiemployer agreement. Therefore it is possible for a non-multi company to win either of the cleaning contracts and pay workers less than the rates in the multi-employer document. For Sina, and others in her situation, legislation protecting vulnerable workers in contract changeovers will make a huge difference because it will provide – o o o o much improved job security – even if there is a change of contract company, they know they will have a job; much improved security of conditions – if there is a change of contract company, they will remain on their terms and conditions, including hours of work, unless they agree otherwise; much greater ability to collectively bargain and to realise real improvements that cannot be undermined or avoided via the contract change-over process; security against discrimination on the grounds of union activity and membership; 21 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 o 22 ability to accumulate leave entitlements from one year to the next, and not to lose these (e.g. sick leave) because of contract change. (h) Graeme works in a distribution centre for a major supermarket chain. When the chain changed hands recently, the new owner used the takeover as an opportunity to attack the pay and conditions of a group of workers in a distribution centre in Christchurch. Graeme says the new owner shut down the distribution centre and made the 32 workers redundant. The company then told the workers they could have jobs at a new distribution centre it was opening two kilometres away, but they would be paid less and would lose some of their conditions. “When the National Distribution Union said they’re doing the same jobs, so they should get the same pay and conditions, the company said it was nothing to do with it as a different company controlled the distribution centre,” Graeme says. “But the distribution centre company is a subsidiary owned 100 per cent by the supermarket.” Only eight of the 32 workers who were made redundant took the jobs at the new distribution centre, because the pay was not enough. Graeme accepted one of the jobs – but at a price. “I was earning around $15 an hour. Now I get $12. It’s a flat rate – all allowances such as shift allowance and penal rates have been taken away.” His sick leave and domestic leave have also been cut. He supports the proposals in the Employment Relations Law Reform Bill that require employment agreements to contain employee protection provisions if a business is restructured or sold. “The company just used the new place as an excuse to cut our wages and conditions – and under the current law it got away with it.” 3.10 There is a significant depth of concern in the union movement about free-riding. This is shown clearly in research by the Department of Labour11. The report noted in its summary12 that: ”Free-riding by individuals on collective terms and conditions has become commonplace in many organisations”. 3.11 A survey which asked free-riders why they did not join the union found that 65.5% said it was because they could get the benefits without joining the union13. DOL, 2003 “Union Research Report: A Component of the Evaluation of the Short Term Impacts of the Employment Relations Act 2000 pp 46-49. 12 Ibid.p 85. 11 22 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 23 3.12 A paper by Blumenfeld et al14 calculates that free-riders make up approximately 24% of NZ workers. The same paper argues that far from addressing free-riding, the Employment Relations Act appears to exacerbate the problem15 and that16: “the only viable solution to the free-rider problem in New Zealand would seem to be permitting the introduction of ‘agency shop’ union security provisions in collective agreements”. 3.13 In the Labour Department survey17 it was reported that over half of unions felt that there had been no change in employer willingness to participate in collective bargaining. Most unions did however find that the significant majority of the employers they deal with act in good faith18. 3.14 The Labour Department has also noted19 that union strength at the introduction of the Act and familiarity with bargaining processes were key variables in their ability to promote the Act’s objective to promote collective bargaining. Unions reporting success were public sector and large private sector unions. 3.15 What has been the experience of employers? Despite the rhetoric we are hearing now, and we heard before the Employment Relations Act came into effect, even strong critics of the new law have given it a pass mark. After six months of the Employment Relations Act, the Employers Peter Haynes, Peter Boxall and Keith Macky (2003) “Union reach and the ‘representation gap’ in New Zealand: contours, characteristics and consequences for unions. Department of Management and Employment Relations”, University of Auckland, mimeo, page 39. 14 Stephen Blumenfeld, Alyn Higgins, Zsuzsanna Lonti (2004), “No Free Lunch : Union FreeRiding in New Zealand”, 18th AIRAANZ Conference, 3-6th February, 2004, Queensland, page 56. 15 Ibid p. 55. 16 Ibid p. 59. 17 DOL, 2003 “Union Research Report: A Component of the Evaluation of the Short Term Impacts of the Employment Relations Act 2000,p 84. 18 Ibid. p 54. 19 Ibid. p.44. 13 23 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 24 and Manufacturers Association examined the Act’s performance and handed out an interim report. EMA’s Employment Relations Manager, Peter Tritt, said the ERA has earned a pass mark overall. He said that: “Employment Relations Service: Excellent. Who would have thought a Government department could perform so well……Employment Relations Authority: Very good. It’s currently quick and effective, but may become subject to demand outstripping supply. Unions: Very good. With 130 unions registered since the Act began, many enterprise based, the new rules regarding union registration can be called a success. The 15 member threshold is mitigating the impact of unions’ statutory monopoly on collective bargaining. New mediation service: Good. Teething problems and some mediators are inexperienced, but overall quick and efficient…..[In]dependent contractors: Fail. The law used to be clear, now it will stay uncertain until judicially interpreted. Written agreements for all new employees: Fail. Noncompliance is pervasive, perhaps as high as 70% among small to medium businesses, who seem unaware or don’t care about the risk of substantial penalties. It’s the same on ensuring new appointees obtain independent advice about their employment agreements. Employment relations education leave: Fail. But no employer is complaining. Course development is just beginning, so the burden of this extra leave on employers can’t be measured. Militant unions: Fail. But it’s not the Act’s fault. The ongoing saga of the wharfies seeking to reclaim their waterfront monopoly with unlawful actions has nothing to do with the new law. Union access rights. Fail. How is it that the law protects minors from unscrupulous employers, but allows open season for union officials to badger young employees about union membership? More strikes? Too soon to tell. Work stoppage figures for the December 2000 quarter are not yet available. But the vets strike illustrated how powerful unions can prohibit the nation’s largest employer from replacing its striking vets. Collectivisation: Too soon to tell. Claims about droves of workers joining the union seem extravagant, but there’s little evidence. Multiemployer collective agreements: Too soon to tell, but the two private sector contracts that survived the ECA have been successfully re-negotiated. Though seen as a Mecca for the trade union movement, no new private sector MECA’s are on the table. Higher wage settlements? Too soon to tell. The nation’s largest union (Engineers) has been a model of restraint during the Act’s honeymoon period with most wage settlements in the 2-3% range. Most settlements involving other unions are in the same band. Employment Court: Too soon to tell whether it is going to head off again into anti-employer decisions that, again, warrant wholesale knocking back on appeal. Good faith bargaining: Too early to tell, but shows promise. After an initial scare over highly prescriptive rules and Treaty of Waitangi obligations, the interim code of good faith looks set to proceed on a sensible basis. There’s no reason to believe why good faith bargaining can’t become an enduring part of our industrial scene as it is in North America. 3.16 This is hardly a condemnation! It demonstrates that even the Act’s fiercest critics acknowledge that it has had only a modest impact. 3.17 In a number of critical areas the Act has been shown to be deficient. The key areas which the CTU has highlighted have been: the failure to 24 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 25 adequately promote collective bargaining; the lack of specificity and enforceability of good faith requirements, the absence of any provisions preventing employers from undermining collective bargaining by using a pass-on of union negotiated benefits, and; the failure to include adequate protections for vulnerable workers in a sale, transfer or contracting out situation. 4. Equal Pay 4.1 This section summarises the CTU’s submission on Part 2 of the Employment Relations Law Reform Bill. The full submission on this Part of the Bill is attached as Appendix 2. 4.2 The CTU notes our longstanding position that there is a need for a legally enforceable right to both equal pay and equal pay for work of equal value. This view has been stated, for example, in the CTU’s regular Article 22 reports to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) on the New Zealand Government’s compliance with Convention 100: Equal Remuneration. 4.3 CTU representatives have played a key role in the Ministerial Taskforce on Pay and Employment Equity which reports on 1 March. It is logical that the Select Committee deliberations on Part 2 of this Bill should be informed by that report, particularly with regard to implications for the public service, public health and public education sectors. The CTU reserves the right to make an additional submission to the Select Committee, including technical amendments that would address issues raised in the Pay and Employment Equity Taskforce’s report. 4.4 The CTU supports the need to improve current equal pay legislation. However we have significant concerns about the equal pay provisions 25 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 26 outlined in Part 2 of the Bill. It is our considered view that the proposed equal pay process is unworkable for the following reasons, namely: 4.5 - The absence of any role for unions in taking equal pay claims - Lack of worker and / or union involvement in choosing a comparator - Lack of transparency about the chosen comparator - No ability to access information required for a claim - Inconsistency with other current legislative provisions - Scope of matters considered is narrower than other legislative provisions - Criteria for establishing a claim is different than the current Equal Pay Act - Very limited ability to compare pay across employers - Labour Inspectors have an insufficient level of authority and expertise - Inability to appeal the Labour inspector’s decision4. The CTU recommends that Part 2 of the Bill is amended substantially, removing the proposed equal pay process and replacing it with new provisions based on the core principles set out in paragraphs 4.6 to 4.10 below. 4.6 The first set of principles outlines the obligation to provide equal pay, and also to provide equal pay for work of equal value in certain circumstances. - An obligation on employers to pay equal pay for the same or substantially similar work - Recognition of the specific needs of workers in predominantly female workplaces, in line with the distinction made in section 3 (1) (b) of the Equal Pay Act 1972. Accordingly, there would be an obligation on employers to pay equal pay for work of equal value. - where work is exclusively or predominantly performed by women AND - workers are employed by the same employer (or employers if they are party to the same MECA) - In the state sector, the government should be deemed to be the employer for the purpose of equal pay for work of equal value claims 26 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 4.7 27 The second set of principles emphasises the requirement that workers and / or their unions are able to choose their own comparator. - workers and/or their unions are able to choose their own comparator from workers employed by the same employer (or employers if they are party to the same MECA) - If the employer disagrees with the nominated comparator/s, the Authority can determine the most appropriate comparator/s. - Where the comparators are paid a range of rates, the Authority shall take into account the range of rates paid and the frequency of the rates paid within the range when assessing the validity of the comparator chosen. 4.8 The third set of principles focuses on the importance of access to information. - Workers and or their unions would have access to the information required to ascertain whether or not they are being provided with equal pay. - Access to this information would be achieved through provisions similar to those contained in section 34 of the Employment Relations Act 2002 4.9 The fourth set of principles stresses consistency with other employment legislation. - The equal pay claims process would be consistent with other employment legislation, using the mediation services in the first instance, with any unresolved claim proceeding to the Authority. This would include resolving any disagreements over disclosure of information. - There would be a six-year timeframe on filing a claim. - There would be a de novo right of appeal in the Employment Court. - Onus of proof would also be consistent with current personal grievance procedures. Accordingly, where prima facie application is made to the Authority, the onus of proof shifts to the employer to justify the differentiation of pay. 4.10 Finally, the fifth set of principles requires effective remedies. - There would be effective remedies underpinning these provisions. 27 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 - 28 Where the Authority determines an employer has not provided equal pay (and/or equal pay for work of equal value in certain circumstances), the Authority can order compliance in addition to arrears of wages and interest and penalties. - In appropriate cases, the Authority can recommend other measures to ensure the employer is meeting their equal pay (and/or specific equal pay for work of equal value) obligations, including recommending an equal pay audit and regular monitoring. 4.11 Given the unwieldy structure of the Equal Pay Act 1972, the CTU recommends that these revised equal pay provisions form a new Equal Pay Act, rather than another amendment to the 1972 legislation. 5. Employment Relations and Economic Performance 5.1 Unions see the improvements in minimum employment rights as complementary to the initiatives in growth and innovation. Unions accept that we cannot impose high wages. They are most likely to come from a period of sustained growth and improvements in productivity as we claw our way up the value chain. But we do need to ensure that there are fair mechanisms available to negotiate on wages and conditions. 5.2 The CTU agrees with the remarks by business commentator Rod Oram20 who has noted that: “if we're to develop a much more highly skilled, productive and innovative workforce - and thus a wealthier economy - then even the smallest firms must figure how to manage their people better, either in-house or with outside help.” He referred particularly to the “urgent need to invest in much stronger skills and more co-operative workplaces”. He said, “employers, employees and their representatives must understand bestpractice human resource management. Then they have to figure 28 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 29 out how to achieve it as soon as possible. Companies and unions which do so will have little problem with the ERA - or each other”. 5.3 The CTU has in fact been arguing for such an approach for over 12 years. In 1992, the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions published a booklet entitled “A Quality Future: Working Together for Growth in New Zealand”. This publication promoted a policy framework for long term sustainable growth with a priority for job growth. The report identified the following commonalities in successful nations and enterprises: o An emphasis on co-operation and consensus o Recognising competition and change as a challenge o Changing technology o Quality at all levels o Less hierarchical management o Flexibility in the face of a constantly changing world o An educated and engaged workforce o Innovation and creativity at all levels 5.4 The report stated that the CTU wanted to “work with others in the community to build an economy which is environmentally sustainable and in which respect for people, their cultures and their rights can be guaranteed”. The CTU at that time, over a decade ago, argued for better monetary policy, positive measures to stimulate economic growth such as research and development, more industry training, improved work practices, and setting new quality standards. The CTU advocated an industry policy (similar to the economic development 20 Rod Oram. “Employer lobbyists’ paranoia is showing”. Sunday Star Times. 1.2.04 29 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 30 programme implemented since 2000) and for social policies based on fairness and personal security. 5.5 In the last few years, unions have consistently advocated support for economic development, growth policies that are inclusive and deliver to all New Zealanders, and for a constructive engagement between employers, unions, and Government. 5.6 The CTU has not argued that employment relations laws are the key drivers of improvements in growth and productivity. In 2000, we said in our submission on the Employment Relations Bill that: The CTU believes that the new Employment Relations Act will have a positive impact on the economy. But consistent with our earlier comments, we do not believe it will have a large impact. In any case, it will be hard to measure. Coincidence does not always show a cause and effect relationship. For instance, we know that wages could be under pressure from skill shortages. There is a predicted decline in unemployment over the next 2 years. And there will a new employment relations law. It will be hard to disaggregate different effects on wages. 5.7 After all, New Zealand has in the past had a booming economy and near full employment at the same time as compulsory unionism, fixed relativities on wages, compulsory arbitration, national awards and many other elements of labour market regulation. But the CTU would not claim that the reason for our relative prosperity at that time was the industrial relations legislation, though arguably it did have a positive effect on the equitable distribution of income. 5.8 Despite some attempts to claim that productivity improved from 1993 due to the Employment Contracts Act, the fact is that we compared 30 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 31 unfavourably with Australia which, despite poor performance in the 1980s, had growth in labour productivity in the 1990s averaging 3.0% (and multi-factor productivity of 1.8%) a year. The general picture is that New Zealand has improved its total factor productivity performance from the 1980s to the 1990s but its total factor productivity growth rate is still pretty average amongst OECD countries. New Zealand labour productivity growth record is near the bottom of the OECD rankings. New Zealand had low growth in physical capital per worker in the early and middle 1990s and that has to be part of the explanation. The Employment Contracts Act did not improve productivity. But clearly, as we stated above, the real drivers of productivity growth are much wider than employment regulatory arrangements. 5.9 GDP figures indicate 3.6% average growth for 3 years under ERA compared with 1.9% for the 3 years before. 5.10 But, in the current labour market, income inequalities persist as much as ever. Employers are responding to labour market shortages by putting more pressure on existing staff. In many cases, they are not paying higher wages, or if they are, they are paying “at the margin”. In other words, they might pay the next individual a bit more, but they are not addressing pervasive low pay. 5.11 Wage rates in New Zealand (adjusted for the exchange rate) are about 25% lower than in Australia. A Canadian research report (September 2003) has revealed that New Zealand workers suffered a drop of 6.5% in real hourly earnings during the 20 years from 1980 to 2001, the worst performance of the 16 OECD countries in the study. By contrast workers Japanese workers were up 69.4%, UK workers 46.9%, Canadian 39.5%, and Australian 28.8%. It is fair to say that the impact of the wage freeze from 1983 was significant. But compared with the 31 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 32 increase in wages through the 1990s in Australia, the increase in New Zealand was a fraction. 5.12 Australia has higher taxes on personal income, more labour market regulation and higher growth, higher wages, and better productivity growth. 5.13 It should also be noted that average number of employees per firm (excluding sole proprietorships) is actually lower in Australia than in New Zealand21. Employer lobby groups often suggest that New Zealand is somehow unique in the size-distribution of firms. In fact, the size-distribution in New Zealand is remarkably similar to the United Kingdom, USA, and Australia. In New Zealand, although 97% of firms employ fewer than 20 workers, the other 3% of firms employ 57% of the full-time equivalent workforce22. Employment laws do of course have to apply to all firms. But when employer lobby groups argue the needs of small business, account should be taken that although the dynamism of small business is a key factor in the labour market, the majority of full-time equivalent workers in the private sector are in firms of more than 20 workers and that there are also 250,000 public sector workers. 5.14 The CTU submits that: real GDP per capita cannot rise without real incomes going up OECD (2004). Economic Surveys : New Zealand, Volume 2003, Supplement No. 3 – January 2004. Page 30. 22 The Ministry of Economic Development publication on SMEs in New Zealand : Structure and Dynamics 2003 indicates the following distribution for actual employees rather than fulltime equivalent employees. All businesses: total public and private sector 281,338 enterprises with 1,467,900 employees. Public sector 3,494 with 250,290 employees. Private sector 277,842 with 1,217,620 employees. Private sector SME is defined as under 20 employees. Private sector small and medium businesses 270,260 businesses with 601,390 employees. Private sector non-SME accounts for 7582 businesses employing 616,230 employees. So, 97% of private sector businesses are defined as SMEs and employ 49% of employees. And 3% of firms are not SMEs and employ 51% of employees. In addition 17% of the labour force is in the public sector with an average of 72 employees in each “enterprise”. 21 32 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 33 although employment growth and hours worked have grown, the Employment Relations Act is not delivering any real redistribution of income we need an employment relations environment that promotes a high wage, high skill, quality economy a sustainable development approach requires that economic growth objectives include social mechanisms to ensure distribution of benefits better pay and conditions for ordinary workers result in household expenditure that will boost growth and employment 5.15 Therefore, the CTU sees a fine-tuned Employment Relations Act as consistent with a sustainable development framework that sets reasonable minimum standards, provides for fair bargaining arrangements, and contributes to a platform for a more co-operative approach both in building a strong economy and ensuring the benefits of economic growth are shared. 5.16 We note also Treasury papers released under the Official Information Act say the overall impact of the Employment Relations Amendment Bill is likely to be modest. 5.17 As business commentator Rod Oram has commented (supra), “the apocalyptic comments of employer groups serve only to diminish their credibility and delay progress on the real issues”. It is the stated objective of the Government to promote a more co-operative good faith culture in New Zealand workplaces. The CTU has been working hard to help unions to engage constructively with employers and Government. That is why unions are actively involved in industry training, and regional and industry development initiatives. We want to use our influence to persuade workers to help realise their vision of a better New Zealand for their families and communities by taking every 33 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 34 opportunity to develop their skills and knowledge. We want to work to develop workforce development strategies, which integrate skill development and health and safety, and optimum conditions of employment to improve productivity. It is very disappointing that the business response to our efforts has been so negative. The CTU hopes that on mature reflection employers will take up our challenge to work together to develop the sustainable growth strategies which will ensure that all New Zealanders are able to enjoy the unique kiwi way of life which we all aspire to. Only then can we make real progress on the “real issues” facing our country. 6. General Comment on Key Provisions in the Bill 6.1 The CTU strongly supports measures in the Bill which more effectively promote collective bargaining. We support collective bargaining because research shows that it provides for better pay and conditions. A collective agreement is just the baseline and individual terms can be agreed in addition provided they are no worse than the collective minimum. Of course, the very reason some employers don’t like collective bargaining is that they prefer to bargain one-on-one with workers, including new employees, as they believe this is better for the employer. Some workers cope well with this situation, but the protection of a collective agreement has been recognised by the International Labour Organisation and the World Bank as providing better protection for workers. 6.2 Why are collective agreements so important? They ensure that bargaining is more likely to on an equal footing between employers and workers. Collective agreements provide a floor. You can still have individual terms and conditions but they cannot be inconsistent with the collective agreement. Collective agreements stay in force after their expiry date (for a year or so) and therefore provide a minimum 34 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 35 protection while bargaining for new conditions. The International Labour Organisation recognises access to collective bargaining as one of the core basic rights of workers. It is from collective bargaining over the decades that workers first got sick leave, health and safety provisions, and extra holidays. The benefits of collective bargaining were also recognised by the World Bank recently.23 6.3 Good faith needs to be strengthened. It should apply to individual bargaining. It also needs to ensure that it clearly goes beyond the implied duty of trust and confidence in employment contracts. The good faith requirements need to be more specific. There needs to be better processes to support good faith conduct and there should be consequences for serious beaches of good faith. 6.4 Unions also support the new provisions in the Bill which address the “freeloader” issue. Unions operate in an environment where it is entirely voluntary to join a union. That remains. But is unfair for union members to pay fees, involve themselves in a bargaining process, attend meetings, maybe even sometimes lose pay to achieve some gains, and then see the employer say to non-union workers that they will get the same deal for free. The provision in the Bill is too weak to really address this matter but it is a start. Unions recognise that sensible arrangements need to apply so that an employer can sort out pay and conditions for all staff, but the current practice of some employers is deliberately undermining collective bargaining. 6.5 We also note ILO jurisprudence which allows employers and unions to voluntarily agree on union security arrangements such as union membership as a condition of employment or payment of a contribution to the costs of the bargaining unit from non-members. We believe that the Bill is deficient in not explicitly providing for this. 23 World Bank 2002.Toke Aidt and Zafiris Tzannatos, Unions and Collective Bargaining: 35 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 6.6 36 A key provision in the Bill is the protection of vulnerable workers in a transfer situation. This has been a longstanding issue and is a common provision in many developed countries. The Bill simply means that if the most economically sensible thing to do is to sell, transfer of contract out the business or part of the business, then this is not done entirely at the expense of the workers. Most employers want employees to transfer on the same or similar pay and conditions. If this cannot occur, most employers will compensate workers. But there are some workers who are not treated this way and have no protection. The Bill addresses this – even though the list of vulnerable workers appears to be too restrictive. 6.7 International Labour Convention 87 is one of the “core conventions” which all member countries are expected to comply with as a condition of ILO membership. Although Convention 87 does not specifically provide for the right to strike the jurisprudence developed by the ILO Committee on Freedom of Association, a tripartite committee of government, employer and union representatives, has long held that the right to strike is protected as part of the right to organise under articles 3, 8 and 11. Legislation that restricts strikes over the level of collective bargaining is not compatible with the Convention. Social and economic strikes are permitted: 482. . . . trade unions should be able to have recourse to protest strikes, in particular where aimed at criticising a government’s economic and social policies.24 It has long been the policy of the CTU to support appropriate strike action on important social and economic issues in the belief that the withdrawal of labour is a legitimate expression of support or opposition Economic Effects in a Global Environment. 24 Ibid. 36 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 37 to particular public issues, which may affect the lives and livelihoods of working people. Such strike action has been rare in New Zealand but has been in respect of issues, which have become some of the major social justice issues of our time. They have included action against nuclear ship visits to our ports and against the Springbok tour. The CTU view has been that such action is in the nature of a civil rights rather than specifically an employment law issue, but the right and protections do need to be reflected in our domestic law, and that the Employment Relations Act should be amended to make clear that the restrictions on the right to strike in the Act do not limit social and economic strikes which have been mandated by the ILO as human rights guaranteed by international law. 6.8 The CTU believes that the Act's objectives can only be achieved by strong and effective unions. Unions play an important role in society. We are important social partners and part of an active civil society. Unions play a crucial role in the labour market in ensuring that disadvantaged groups are represented and that all workers have access to democratic organisations that can advance their interests. The role of employment legislation is to provide a legal environment where strong, effective and democratic unions can function in the interests of workers and society as a whole. 6.9 Two key ways in which unions can be supported to ensure that the Employment Relations Act really does create a fair basis for unions in the labour market are to support MECA bargaining and address the free riding issue. Changes around good faith in individual bargaining and not undermining bargaining will not be enough on their own. 7. Summary 7.1 The CTU supports this Bill. 37 Employment Relations Law Reform Bill CTU Submission 28 February 2004 7.2 38 The CTU has significant concerns about deficiencies in the Bill and these are elaborated on in the detailed technical amendments set out in the attachment. 38

![Labor Management Relations [Opens in New Window]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006750373_1-d299a6861c58d67d0e98709a44e4f857-300x300.png)