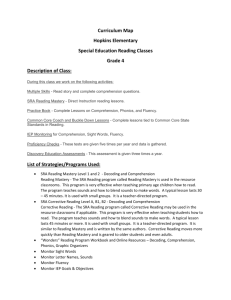

Special Education Literacy Initiative

advertisement

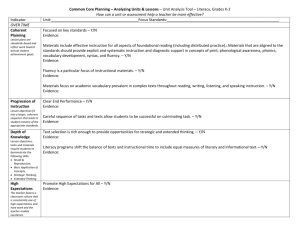

Warren County Schools Special Education Literacy Initiative Building, Implementing, and Sustaining INTRODUCTION In 2005, Warren County Schools undertook a Special Education Literacy Initiative to help “close the gaps” between our students with special needs and their nondisabled peers. As part of this initiative, SRA’S direct instruction programs Reading Mastery, Corrective Reading, and Language for Learning/Thinking/Writing were adopted. These programs offer research-validated program designs, proven instructional practices, and results measured through scores of comparative studies. The purpose of this document is to provide additional information about the selected programs and outline procedures for monitoring progress and adapting instruction to help all students reach proficiency. The Reading Mastery Classic program was developed as a basal reading program. For special education students in Warren County, this program is primarily being used for students in P1 through P5. It is designed to advance students to the following grade levels once completed: Reading Mastery Classic I Reading Mastery Classic II 1.4 grade level 2.4 grade level The Corrective Reading Decoding program was designed for students in fourth grade and above that are at least two years behind in reading. Within Warren County, for special education students, this program is being used in the intermediate, middle, and high school levels. After a student completes a Corrective Reading program, their estimated reading level would be as follows: Corrective Reading Decoding A Corrective Reading Decoding B1 Corrective Reading Decoding B2 Corrective Reading Decoding C 2.0 3.0 4.0 5-7.0 Reading 60 words per minute Reading 90 words per minute Reading 130 words per minute Reading 150 words per minute In order to individualize instruction based on student needs and bridge the gap to CATS (Commonwealth Accountability Testing System), additional literacy programs being utilized within special education in Warren County include the following: Earobics computer software to advance phonemic awareness skills Open Book to Literacy computer software to demonstrate physical characteristics for making sounds and build phonemic awareness and phonics skills Language for Learning/Thinking/Writing to support oral language development Scott Foresman Sidewalks Intervention Kits to support regular class instruction Reading Mastery Connections provides Reading First strategies (e.g., partner reads, readers theatre, etc.) to support the Reading Mastery program and philosophy Corrective Reading Connections emphasizes Reading First strategies (e.g., echo reading, reading in phrases) to use along with Corrective Reading Decoding series Horizons Fast Track C-D is a combination of Reading Mastery III and IV used for intermediate students who can not be successful in the regular reading class and need additional emphasis on decoding, vocabulary, and comprehension REWARDS multisyllabic word study program Read 180 for further instruction in vocabulary and comprehension Achieve 3000 to provide high school level text at students’ instructional reading level Corrective Reading Comprehension to provide an emphasis on higher order thinking and reasoning skills Plugged-In to Reading to build higher level thinking and comprehension skills through fiction and non-fiction passages PROGRESS MONITORING The Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS) are a series of brief fluency measurements that accurately predict reading outcomes. This ongoing assessment measure along with a brief word recognition test will be used across the district to monitor student progress and improve instructional programming. The DIBELS results will be analyzed periodically at each school by a literacy team composed of some or all of the following: principal, special education teacher, regular education teacher, elementary curriculum coordinator, school reading coach, district teacher consultant, district special education literacy consultant, and parents. This group will be assembled to discuss the results and determine the effectiveness of the interventions being employed. Goal setting is a complicated part of this process. Writing a goal that a special education student is expected to make less than one year’s growth in the general education curriculum is constructing an intervention that will leave a student farther behind general education peers. Expecting a student to make more than one year’s growth in general education curriculum is constructing an intervention that, if successful, will bring the student’s skills nearer to those of his nondisabled peers. (Shinn, 2002). As part of the literacy’s team’s analysis, the student’s growth will be considered in comparison to his “absolute” learning target. This would be the on-grade level DIBELS benchmarks listed in the attached chart. “Relative” learning targets will be individualized. These expected rates of short-term growth will be based on mastery tests from the programs, knowledge from the field of special education (see below), and the literacy team’s professional judgment. A strong positive slope of progress will be expected for all students. If it is determined that appropriate progress is not being made for each individual student, a plan of action will be developed. According to Fuchs & Fuchs (2006) and Shinn, Walker, & Stoner (2002), customizing interventions may include any of the following adaptations: Making instruction more teacher-centered, systematic, and explicit Conducting the instruction more frequently Adding to the duration of the instruction Creating smaller, more homogeneous student grouping Increasing the knowledge of the instructors through professional development activities In addition, supportive programs such as those listed above may be utilized as part of the action plan to further support the students demonstrating minimal to no growth. However, staff must assure that any program being used must be implemented with fidelity. SUCCESSFUL IMPLEMENTATION Successful implementation of these direct instruction reading programs depends on two main factors. First and foremost, students must reach mastery before advancing to the next lesson. One of the primary philosophies of these programs is that students are not given tasks without first being systematically and explicitly instructed on how to complete the task. The concept of guessing is no longer encouraged or needed. Therefore, checkouts and mastery tests are an integral part of the instruction and provide valuable feedback to the teacher about changes that may need to be made in instruction. The second factor that greatly influences student academic growth is one’s progress through the program. We must recognize that the urgency in providing intensive reading instruction (at a fast pace) as our students with special needs are significantly behind the reading levels of their peers. Research suggests that all primary students must receive at least 90 minutes of reading instruction daily and 60 minutes for intermediate students. Struggling students need even more time being directly instructed in reading if they are to “catch up.” The literacy team should analyze each student’s schedule to determine if they are receiving adequate reading instruction throughout a school day. This may include instruction within the regular classroom setting with nondisabled peers in addition to specialized instruction from special education personnel. In addition, coaching and advanced training is essential to make these instructional programs effective. According to district data collection, coaching and training have been imperative in building our teachers’ skills. This has had a direct and profound impact on student learning. REFERENCES Deno, S.L., Fuchs, L.S., Marston, D. Shin, J. (2001). Using curriculum-based measurement to establish growth standards for students with learning disabilities. School Psychology Review, 30 , 507-524. Engelmann, S., Bruner, E.C. (2003). Reading Mastery. Columbus, OH: SRA/McGrawHill. Engelmann, S., Hanner, S., and Johnson, G. (1999). Corrective Reading. Columbus, OH: SRA/McGraw-Hill. Engelmann, S., Osborn, J. (1999). Language for Learning. Columbus, OH: SRA/McGraw-Hill. Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L.S. (2006). Introduction to Response to Intervention: What, why, and how valid is it? Reading Research Quarterly, 41, 93-99. Fuchs, L.S., Fuchs, D., Hamlett, C.L., Walz, L., & Germann, G. (1993). Formative evaluation of academic progress: How much growth can we expect? School Psychology Review, 22, 27-48. National Reading Panel. (2000). Put Reading First: The research building blocks for teaching children to read. Washington DC: Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement. National Research Council. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington DC: National Academy Press. Shinn, M. (2002). Best practices in using curriculum-based measurement in a problemsolving model. Best Practices in School Psychology IV. Washington DC: National Association of School Psychologists. Shinn, M., Walker, H., Stoner, G. (2002). Interventions for academic and behavior problems II: Preventative and remedial approaches. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Torgeson, J. (1998). Catch them before they fall: Identification and assessment to prevent reading failure in young children. American Educator/American Federation of Teachers, Spring/Summer, 1-8. Mary Ellen Simmons Director of Special Education Vickie Embry Teacher Consultant Christy W. Bryce Special Ed. Literacy Consultant