Gimme Shelter: Planning for Terrorism and Other Disasters

advertisement

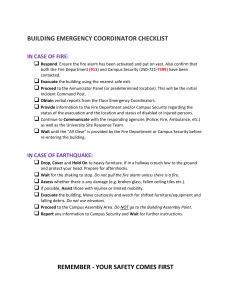

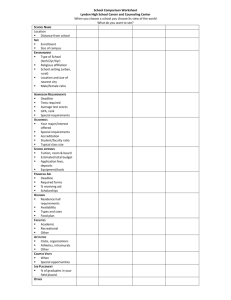

GIMME SHELTER: PLANNING FOR TERRORISM AND OTHER DISASTERS June 16-19, 2004 Bethany J. Bridgham, Senior Associate General Counsel American University, Washington, DC Introduction College communities can represent the best-of-all-worlds and the worst-of-allworlds. In-house counsel are regularly called upon to plan for the unthinkable, render advice on the unknowable and provide guidance for the unforeseeable – while maintaining a sense of humor through it all. Consequently, planning for terrorism and other disasters is well within our abilities and job descriptions. Time spent planning for and anticipating disasters in advance of those occurrences – of whatever shape, size or form –is time well spent. The middle of a crisis is not the time for initiating the planning process or assembling your response team. Time spent now will yield huge dividends later. The events of recent years – natural disasters, terrorism, financial misconduct and collapse, attacks on technology systems – emphasize that our thinking of what constitutes a “disaster” or an act of terrorism is very different than our perspective from even a few years ago. Given these broader definitions, the plan you develop for emergency preparedness should be flexible and adaptable so that it can be regularly updated based on changes in your organization, as well as changes in the external community, without requiring a complete overhaul or expensive modifications. In addition, a plan best suited for use by a college or university might be one that focuses not only on preventing attacks but also preparing for such an event so as to mitigate the resulting harm. There are over 6,400 degree-granting institutions in the United States.1 Their sizes vary widely, as do their locations. Some are private, some public, and their academic missions range from the purely technical to the arts. With each of these variations, come different risks and needs. For these reasons, if you rely on an “off-theshelf” or boilerplate-type of plan, the risk increases that when a disaster occurs, the plan will be inadequate for the needs of your organization and could create more problems than solutions in the middle of a crisis. 1 "Postsecondary Institutions in the United States: Fall 2001 and Degrees and Other Awards Conferred: 2000-01" in Vol. 5, Issue 2, Topic: Postsecondary Education. The Article was by Laura G. Knapp, Janice E. Kelly, Roy W. Whitmore, Shiying Wu, and Lorraine M. Gallego. National Association of College and University Attorneys 1 I. Securing Your Campus in the Face of Terrorism, Disasters or Other Crises A. Special Security Issues Faced By Colleges and Universities It is all but impossible for a college or university to develop a plan which is either an ironclad terrorist-prevention plan or that will provide absolute assurances that the campus will be absolutely secured in the case of such an event. The nature of college campuses (open space, easy building access, populations –whether faculty or student – who are resistant to security measures which present real or perceived restrictions to their liberties) make these sites hard to secure and, in some cases, tempting targets. Terrorist attacks can take many forms and do not always involve the loss of human life. Denial of service attacks can cripple information systems or animal liberation groups can destroy years of research and millions of dollars worth of equipment without ever causing any physical harm to human beings. The precipitating event may not even be deliberately hostile in nature. In Washington this past year, a student at a local high school took mercury from a chemistry lab without permission.2 He shared it with other students, some of whom threw it in the halls, where it contaminated shoes, clothing and facilities. With a student population of 1,300, the chemical was then tracked throughout the school, onto city buses and into students’ homes. By the time the situation was finally contained and the clean-up complete, the school was closed for a month, classes were rescheduled at various sites around the city, apartment buildings had been evacuated, more than 100 homes were tested and 69 people were displaced from contaminated homes. Although the student deliberately took the chemical, it appears that he did it as a prank and not to precipitate an environmental hazard. Nor is it clear that he understood the chemical’s toxicity or the danger it – and his actions -represented to himself and others. The city and school officials were roundly criticized in the aftermath of the event. Allegations were made that calls to 911 were delayed and what was perceived as poor communication between school officials and parents and students left many individuals angry and frustrated.3 The decision to allow students to leave the building was also criticized as it permitted the contamination to spread from the building to private homes, multi-family buildings and public transportation. Because mercury vapors are a health threat, its presence in areas with high-capacity air intake systems, such as apartment buildings, spread the potential hazard exponentially. Any college campus attempting to contain a similar situation would be faced with many of the same issues – how to prevent the hazard from contaminating large residence Fahrenthold, David – “Mercury is Stolen, Spread at Ballou High; SE School Closed Through Weekend”, The Washington Post, Oct. 3, 2003. 3 Blum, Justin and Manny Fernandez – “Gaps Marked Response to Mercury Spill”, The Washington Post, Oct. 18, 2003 2 National Association of College and University Attorneys 2 halls, public transport, dining facilities, classroom space, while facing intense media scrutiny and demands for information from concerned parents and students. In general, the type of threats any college or university should expect to face can be grouped into five broad categories: 1) Natural - hurricanes, tornadoes, floods earthquakes, disease 2) Environmental and chemical - spills or releases of hazardous materials, manmade hazards (buried material) 3) Facilities - attacks against physical resources, bombs, fire, loss of utilities 4) Technology - denial of service attacks, computer viruses, physical damage to technology resources 5) Human - workplace violence, hostage- taking, riots, vandalism, town-gown issues, administrative or governance problem B. Basic Security Measures and Conducting Risk Management/Threat Analysis The implementation of basic security measures should be integrated into your campus culture on a daily basis. This is unlikely to be a popular decision as many people view protective security measures as intrusive and inconvenient. Too often, heightened security measures are employed only after an event and then quickly eliminated due to complaints from individuals who find them time-consuming or disruptive. Basic security measures that should be employed daily and as part of your emergency preparedness plan, include: 1) public safety officers – foot, bicycle and vehicle patrols 2) physical security - fences, locks or any other form of access control which employs physical obstacles to entry 3) closed circuit television and alarm systems 4) searches - may include people, vehicles, possessions 5) technical security - antivirus software or disabling firewalls As part of employing these basic security measures, your team should also conduct a security analysis, identifying the risks that exist on campus. These may include: security; compliance; strategic; external; internal; operational; financial; reputation and legal. Once identified, these risks should also be quantified in terms of the probability that they might occur and potential measures to counter these risks should be researched. National Association of College and University Attorneys 3 Among these possibilities are: 1) 2) 3) 4) II. transferring the risk. Obtain insurance coverage or contract the service out to a third-party vendor with experience in the area; tolerating the risk. In some instances, it may not be possible to obtain insurance or securing the services of a third-party vendor or these options may not be cost-effective. If this option is selected, you will need to monitor the risk to ensure that there have been no changes which might increase the likelihood of occurrence. treating the risk. Modifications in procedures or policies may reduce the risk to an acceptable level. terminating the risk. The institution may decide that continuing the activity or service creates an unacceptable level of risk and should be terminated altogether. Emergency Preparedness Plan – Getting Started A. You Need a Committee “Committees are a group of the unfit appointed by the unwilling to do the unnecessary.” 4 Most of us serve on a variety of campus committees, some more effective than others. Whether or not you believe committees provide meaningful results, one important aspect of these committees is that they often bring together segments of the campus community that otherwise would not have the opportunity to interact. It is exactly this aspect of committees that will provide a critical piece in formulating the process of developing your emergency preparedness plan. Your institution may already have a safety or risk management committee which is responsible for taking the broad perspective in identifying and proposing solutions to risk management and safety issues ranging from university driver safety to disaster planning. Depending upon the activities undertaken by your institution, this group may also include oversight of hazardous materials, animal care and use, and the institutional review board. Each of which also presents an area for acts of terrorism or other disasters. Emergency preparedness may be undertaken within the context of this committee’s normal activities or you may decide to establish a separate group which focuses strictly on the topic of planning for, and recovery from, disasters. No matter which route your institution takes, the process of planning for the before, during and after of disasters is time-consuming. Realistically, you should anticipate the process will take at least one full year, if not longer. More important is to recognize that, once prepared, Niehoff, Len, “Campus Security and Crisis Management: Best Practices – Some Observations for the College or University Lawyer”, NACUA June 2002, quoting Carl Byers. 4 National Association of College and University Attorneys 4 the plan will need to be kept current, updated on a regular basis and be familiar to the people who will be called on in a disaster or emergency to execute the plan. Because the issues of safety, security, business continuity and disaster recovery cut across all departments, the committee’s membership should include representatives from as many divisions as possible. At my university, our committee included members from the faculty, risk management, facilities and physical plant, housing, technology, health services, media relations, academic affairs and the general counsel’s office. Our group was charged with developing a plan to address not only emergency preparedness but also business continuity and disaster recovery. B. Internal and External Assessments In order to ensure that your plan is appropriate for your school, you should start with a comprehensive safety or risk management audit. We conducted both internal and external assessments to provide a much broader look at the potential issues we were facing. The committee developed a questionnaire for internal use to gather feedback from department heads or other decision-makers to ascertain what they viewed as the most important functions provided by their areas and what critical resources they would need to serve the university community in the event of an emergency (See: Exhibit One draft example of questionnaire.) The questionnaire asked what other departments the responding departments relied on and which ones were reliant on them, minimal staffing levels, necessary equipment and supplies and how much of their work could be performed from home or another non-campus location. The data from these questionnaires was collected and provided an excellent source of information for the forward planning undertaken by the university to assess what resources would be needed at what points along the timeline of a crisis and the recovery from such an event. Based on the information gleaned from our questionnaire, it was immediately apparent that many responders placed a top priority on telecommunications and computer access. But, we were also able to ascertain that most of our population had redundant capabilities -- i.e., cell phones, home phones and separate internet service providers -- so that we would not be faced with having to provide immediate service to our entire campus population on the first day of a crisis that had affected our technology resources. This information was also helpful to the committee in developing a request for proposal (“RFP”) which was used during discussions with outside vendors. In addition to the internal assessment, your institution should secure an outside, independent vendor, with experience in the field, to conduct a top to bottom risk assessment and safety audit. You should anticipate, however, that the results of this audit may well reveal a number of items that need to be fixed immediately and/or contain information which the institution would prefer not be widely available. Consequently, while your institution’s safety committee may be charged with developing the plan which will respond to the safety and risk management issues identified, it would be wise to do National Association of College and University Attorneys 5 some upfront planning to ensure that the results of such an audit are protected by the attorney-client privilege. C. Protecting the Results of the Audit Start with a clear definition of the purpose of the audit. The senior administrator or chair of the committee should send a written memo to the general counsel, which provides a detailed description of the issue. This written memo should include: a) an overview of the problem and a specific request for legal services from your office pertaining to this matter; b) a specific written directive asking that your office oversee the audit to determine what, if any, legal liability the institution may face as a result of the problem; and c) where the final report or summary should be sent once the investigation, including data collection and analysis, is complete. Increased involvement in non-legal affairs can create the impression among the campus community that anything discussed at a meeting at which counsel is present is protected by the attorney-client privilege, which, realistically, is not the case. In general, there is a two step process in determining whether a communication is covered by the attorney-client privilege and not subject to discovery by the opposing party. First, does the communication satisfy the traditional definition of attorney-client privilege ? [The privilege applies if the asserted holder is or sought to become a client. The person to whom the communication was made is a lawyer and was acting as a lawyer in connection with the communication. The communication must relate to a fact of which the attorney was informed by the client, without any strangers present. The client made the communication for the primary purpose of obtaining an opinion on the law, legal services, or assistance in some legal proceeding and not for the purpose of committing a crime or tort. The privilege has been claimed and not waived by the client. United States v. United Shoe Mach., 89 F. Supp. 357 (D. Mass. 1950)] Second, the federal courts and most states apply the factors discussed in Upjohn: i) ii) iii) iv) the communication was made by an employee to counsel upon the order of superiors in order to secure legal advice for the organization; the information needed by counsel to formulate the legal advice was not available to senior administrators; the information communicated concerned matters within the scope of the employee's duties; the employees were aware that the reason for communications with counsel was so the corporation could obtain legal advice; and National Association of College and University Attorneys 6 v) the communications were ordered to be kept confidential and they remained confidential. Upjohn Co. v. United States, 449 U.S. 383 (1981) Merely having the attorney request the investigation or action is not sufficient, absent other actions by the attorney, to cloak the subsequent work product within the attorney-client privilege. In United States v. Adlman, 68 F.3d 1495 (2d Cir. 1995), the Court found a tax opinion on a proposed merger, rendered by an accounting firm at the request of in-house counsel, was not a protected attorney-client communication. The Court found the following factors persuasive in making its decision: a. the corporation had regularly employed the accounting firm; b. the accounting firm's services in connection with the contemplated merger were not billed separate from the accounting firm's regular duties; c. the accounting firm provided all the research and work product for the report on the merger; and d. the report was sent directly to the corporation's management and not to the in-house counsel. D. Assembling the Team The committee which creates the emergency preparedness plan is likely to also be involved in executing the plan in the event of an emergency. However, the implementation of the plan will involve many more people, who should be clearly identified and briefed on their roles and responsibilities before the plan is adopted. When selecting the members who will enact the plan, select a cross-campus population from a variety of departments. In addition, the more people who are involved and understand what the response plan is during an emergency the greater the likelihood that the plan will be successfully executed even if several key team members are lost during the emergency. In developing your response team, also consider developing an overall team which then contains smaller response teams, whose skills sets match more closely with the nature of the emergency. For example, public safety officers will likely always be on hand but physical plant employees with expertise in hazardous materials may only be required for environmental or chemical emergencies. Similarly, although the contracts administrator may have been instrumental in developing the RFP soliciting an outside vendor and in negotiating a Memorandum of Agreement with that vendor, he or she may not have the skill set the university needs in order to secure food and housing for 5,000 displaced students. Some examples of the tasks members of your team will be faced with include: 1) restoring telecommunication resources National Association of College and University Attorneys 7 2) providing food and housing to displaced populations 3) securing facilities and other resources, including special collections such as the library, archives and art museums 4) limiting access to campus 5) protecting individuals from harassment 6) providing health care services 7) protecting business records 8) providing transportation - either local, national or international 9) communicating with members of the internal and external community 10) coordinating the emergency response teams from local, state and federal agencies The team you select should have the capabilities and authority to meet these challenges. III. The Complete Emergency Preparedness Plan In evaluating our present crisis response plan, we determined that the university would be best served by utilizing the services of an outside vendor with experience in the field. Our review showed that past plans had proven to be hard to update, hard to locate (i.e., most people put it on a shelf and then forgot it was there) and that a significant segment of our campus community did not know these plans even existed. Consequently, when we developed our RFP inviting companies to submit proposals we specifically asked that the proposals include plans for ongoing consulting services in contingency planning, including on going training, and solutions to keeping the plans current and updated as the university's personnel and needs changed. We asked that the plan provide detailed steps for loss of information, loss of access to information and facilities and loss of people. (See: Exhibit Two - an example of an RFP requesting services.)5 Many colleges and universities post their plans – or segments of their plans – on their websites and these plans can provide a good first step in organizing the information, policies and procedures you believe your plan should contain. (See: http://www.newpaltz.edu/police/emergency and http://www.pfm.howard.edu/emergency for examples.) Although each plan should be tailored to the unique characteristics and needs of your institution, there are some commonalities that an emergency preparedness plan should address. These include the following: 1) what are the institution's priorities during a crisis situation? 5 Some of the outside vendors offering these type of services include: Berstein Communications, Inc.; Bowne DecisionQuest; Dewberry and Davis LLC; Kroll Associates, Inc. and URS Corporation. National Association of College and University Attorneys 8 a. These might include protecting human life, preventing or minimizing injuries, protecting the physical resources and facilities of the institution and resuming operations as quickly as possible. 2) who declares an emergency and what are the factors that go into the decision. Will there be different levels of emergency? For example, a natural disaster (tornado, hurricane) that reached campus would be treated differently than a non-specific anonymous threat that harm might come to campus. 3) who is in charge during an emergency? Who will take part in the management of the emergency? a. The plan should include instructions for what roles and responsibilities each person is assigned. If critical members of the team are lost during the emergency, you should have some means of ensuring that their loss will not create a critical failure in the execution of the plan. 4) where are the command center and the alternate or back-up location? How will the crisis managers reach this site? 5) how will you communicate this decision to the campus community? Where can people obtain and/or report new information? Do you have redundant systems in case the primary systems are disabled during the emergency? How will you communicate this decision to the external community – including the media? 6) key contact information - both for members of the crisis management team as well as critical internal and external resources - i.e., fire, police, federal agencies, etc. 7) evacuation plans, designated gathering sites or shelters, shut down procedures for buildings, including utilities (electricity, heating and cooling systems, water), the location of building and engineering plans, a current campus map. 8) instructions for dealing with the media. a. You should prepare for intense media scrutiny and get out in front of the onslaught by anticipating those demands. Identify a site for media briefings, preferably one that insulates reporters from the incident, and identify an alternate site in the event the campus is inaccessible. Expect that you will be asked to provide space for press briefings, telecommunication hook-ups, such as computer and phone services, and parking. National Association of College and University Attorneys 9 9) your institution’s policy on releasing the names of people who are implicated or connected to the incident, including the names of those injured or killed. Your institution’s policy on releasing or confirming the names of students, faculty, staff or members of the Board of Trustees. 10) general information about your institution, its history, size, number of students and/or employees. Although these items should be included in your institution’s plan, access to some of this information should be limited to members of the crisis response teams or others on a need to know basis. For example, access codes for building alarms or the contact information for the members of the crisis response team should remain confidential. Many institutions have posted their emergency preparedness plans on the internet but implemented password protection for sections of those plans deemed to contain sensitive or confidential information. (See: For example, James Madison University’s plan at: Http://www.jmu.edu/safetyplan/contents or American University’s plan at: http://www.american.edu/finance/rmo/toc.html). A. Training, Testing and Revising your Plans Reduced to its most basic element, terrorism represents a risk which requires an active risk management strategy. Depending upon the location, culture and activities of your institution, the risk of terrorism may appear more remote -- or realistic -- than that of your comparator institutions. However, whoever you are and wherever you are, the risk of terrorism can no longer be dismissed as a remote possibility. Being prepared does not -- and likely never can -- mean that you are one hundred percent secure and, that because of your preparedness, you will never experience a crisis or disaster. What it can mean, however, is that you have planned ahead and identified the resources, people and lines of communication that you will need in the event of a crisis. This planning should include not only the internal but also the external and how these two will interact. Even if your internal team has successfully conducted multiple drills and its members are clear on their responsibilities during an emergency, your careful planning may be turned upside if the crisis involves a situation where an external agency has the right to take command and oversee the management of the situation. Many jurisdictions will have already developed a set chart which indicates who is in charge depending upon what circumstances. You will need to determine under what circumstances these agencies may have the authority to enter your campus and take over and how that will alter the implementation of your plan. One valuable learning tool is to participate in a joint practice drill or table top exercise so that everyone is familiar with their roles in a crisis situation. This includes not only situations where you will be jointly responding but also situations where your National Association of College and University Attorneys 10 institution might be responding alone and the outside agencies are merely on standby. Input from these external groups, with their years of experience in the field, can provide invaluable practical advice on what they perceive as strengths or weaknesses in your plan. Keep these groups apprised of your procedures, regularly updated on changes in procedures or personnel and involved in all future practice drills. Agencies and organizations you may need to rely on in an emergency are listed below and many provide information on their websites to assist you in the planning process. Police Fire Ambulance/First Responders Local hospitals and trauma centers Homeland Security - http://www.dhs.gov/dhspublic/ American Red Cross - http://www.redcross.org/ CDC – http://www.bt.cdc.gov Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry - http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ FBI - http://www.fbi.gov/ Secret Service - http://www.ustreas.gov/usss/index.shtml Military/National Guard Federal, state and local emergency management resources - FEMA http://www.fema.gov/fima/dru.shtm, including a specific section on “Building a Disaster Resistant University” and exemplary practices in emergency management http://www.fema.gov/library/partnrprep.shtm - Two listing planning procedures for individuals with disabilities Emergency Planning for People with Disabilities http://www.eeoc.gov/facts/evacuation.html Emergency Procedures for Employees with Disabilities in Office Occupancies http://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/fa-154.pdf Emergency food and shelter - local hotels and restaurants In addition, certain segments of your plan, or even every day business or security procedures, may be impacted by the multitude of federal legislation enacted since the National Association of College and University Attorneys 11 events of 9/11. A listing of these statutes, including website links, is located at Exhibit Three. IV. Media and Communication The first comments you make at the beginning of a crisis or other disaster can set the tone for the life of a story. Thus, it is important that the institution provide complete and accurate information as quickly as possible. Journalists will bring their own biases to any story. Although they may try to report in a balanced manner, it is still through their perspective that your story will be reported to the public - who may include future and current students, alumni, financial supporters, friends, family, and, depending on the nature of the crisis, members of the jury pool in related litigation. These early contacts are critical in establishing the tenor and tone of the media coverage to follow. In developing your emergency preparedness plan, consider preparing preapproved canned holding statements that can be used for a variety of situations. For example, statements which would apply to both internal and external situations and only need to be personalized for the specific situation. (See: Exhibit Four – example of advance holding statements.) Prepare a list ahead of time of people who will need to receive this statement so that everyone is providing the same information to anyone who inquiries. In this electronic age, news spreads instantly across state lines, across the nation and even across the globe. Ignoring the problem or the phone calls from the media will not make the problem go away and a slow news day can quickly turn your situation into a full blown crisis. One of the most critical decisions you will make is determining who will act as the official university spokesperson for this event. Depending upon the situation, it may not always be the same person. For example, a threat involving the entire campus may require a statement from the university’s president. A situation involving an external threat that may or may not ever impact the campus may be appropriate for the director of media relations to address. I would recommend against having in-house counsel acting as the university's spokes person. In attempting to deliver the message, it is possible that your words or actions could be construed as a waiver of either the attorney-client privilege or the work product doctrine. (See: United States v. Dakota 197 F.3d 821 (6th Cir. 2000) and Columbia/HCA Healthcare Corporation Billing Practices Litigation 293 F.3d 289 (6th Cir. 2002). Although it is important that you provide accurate information in response to media inquiries, you must also anticipate the consequences of these statements in the event of future litigation. A. “Off the Record” and Other Myths From the Media Game National Association of College and University Attorneys 12 When dealing with the media, almost everything is fair game - marital affairs, nasty divorces, nuisance lawsuits -- which may have absolutely no bearing on the crisis at hand. Crises attract reporters who know little about your institution, its history or culture. You should anticipate that in the early stages, a large part of dealing with the media will be conducting building block education about the institution – its goals, academic mission and history. Don't ignore questions that seem ignorant or off topic – take notes, promise to follow-up (and make sure you do!) but then return the conversation to the situation at hand. In delivering your message, you should use two or three simple messages in onthe-record conversations, backed up by simple examples and straight forward promises to get to the bottom of a problem, with continued references to your positive history and contributions to the community. Above all, always tell the truth and provide as accurate and up-to-date information as possible. Don’t speculate, pass on rumors or otherwise lend credence to items which you can not factually substantiate or document. The deadlines in a crisis situation are unbearably short but you should resist the temptation to put something out that is inaccurate or based on faulty information just to satisfy their demand for information. However, even if you issue nothing more than a statement of concern and a promise to investigate that is better than allowing a story to air for which you either issued a “no comment” or failed to have any input. Always assume when you are talking with a reporter that you are on the record. While attorneys are used to confidential discussions and offers in settlement, there are no such niceties when dealing with the press. Once a statement is attributed to you or your institution, it will be out there forever. Retractions and corrections are never afforded the same position as the original page one story and rarely reach the audience who read and remember that first damaging quote. And, unlike a courtroom, the press provides the avenue for the public to act as judge and jury, what they report is what the public will hear. In order for you to present your best case, you must be able to deliver a message that your institution is doing the right thing in a difficult situation. B. Developing a Media Communication Plan Steps to follow in developing a media communication plan include: 1) what are your key messages? Reduce them to writing and distribute them to key administrators or anyone else likely to be in contact with the press. 2) select the appropriate spokesperson to deliver the message. In some instances, it will be the president, for others it may be the director of media relations. 3) select a media gathering spot and advertise it. This will cut down on the number of media wandering around on campus. You control the story, you control access. National Association of College and University Attorneys 13 4) determine in advance the decision making structure for dealing with a crisis. Misinformation or stone-walling inquiries will only lead to larger problems later. It is important that the institution control the message, get out in front of the story and appear to be exercising leadership and control of the situation. 5) find out all the relevant facts. Deal only with confirmed information - don't repeat rumors. Establish a website or phone recording where individuals can call for regular updates. This will also serve to drive non-essential traffic off of telecommunications lines which are needed for crisis response. Conclusion The events of recent years, ranging from natural disasters to terrorism to financial misconduct, emphasize that our thinking of what constitutes a “disaster” or crisis is very different than our perspective from even a few years ago. The plan you develop for emergency preparedness should be flexible and adaptable so that it can be regularly updated based on changes in your organization, as well as changes in the external community. It should be designed to not only prevent attacks but also prepare for such events so as to mitigate the resulting harm. National Association of College and University Attorneys 14 Exhibit One - DRAFT – FOR DISCUSSION PURPOSES ONLY SAMPLE PREAPREDNESS QUESTIONNAIRE GENERAL 1) Identify your department’s principal activities. Identify which are critical functions - those that are necessary to avoid academic disruption. Which must be restored in the first hour? First day? First week ? First month ? After one month ? 2) Are there internal departments which you are reliant on? Others that are reliant on you? 3) Are there rules, regulations contracts or other obligations that require the delivery of services or products from your department? Critical clients or prospects? 4) What are your hours of operation? 5) How do you secure and discard confidential information? 6) In the event of a community-wide disaster, would there be opportunities or needs for your services? STAFFING 1) What is the minimal level of staffing required to conduct your critical functions identified earlier? 2) Do you have documentation that describes the required skill level of your staff to perform these functions? 3) Do you have any physically challenged staff? If so, what workplace accommodations are needed? 4) Have there been any past incidents that caused the disruption of your daily activities? How long did the disruption last? 5) What, if any, department business could you conduct from home or another location? EQUIPMENT AND SUPPLIES National Association of College and University Attorneys 15 1) Identify critical equipment or supplies needed to do your job. What additional supplies or equipment are needed? List by priority and provide quantities. 2) Identify critical services that you are dependent upon. 3) Identify critical outside vendors. 4) If critical equipment was not available, is there an alternate method to perform critical functions? How efficient is this alternate method? 5) Are there are hazardous materials in your department? If so, please identify. 6) Do you have a material safety data sheet (MSDS) for each hazardous material? National Association of College and University Attorneys 16 Exhibit Three – Recent Federal Laws Impacting Security, Terrorism and Emergency Preparedness Homeland Security Act of 2002 http://www.dhs.gov/dhspublic/display Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act of 2002 http://rpc.senate.gov/_files/L37IMMIGRATIONjj041102.pdf Maritime Transportation Security Act of 2002 http://ntl.bts.gov/card_view.cfm Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 http://www.fda.gov/oc/bioterrorism/bioact.html http://www.ncsl.org/statefed/health/PL107-188overview.htm Terrorist Bombings Convention Act of 2002 http://www.govinst.com/PDFFiles/HS/Terrorist_Bombings_Act.pdf Aviation and Transportation Security Act of 2001 http://www.tsa.gov/interweb/assetlibrary/Aviation_and_Transportation_Security_Act_A TSA_Public_Law_107_1771.pdf USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 http://news.findlaw.com/hdocs/docs/terrorism/hr3162.pdf 2002 Supplemental Appropriations Act for Further Recovery from and Response to Terrorist Attaches on the U.S. Coast http://www.fas.org/asmp/resources/govern/107th_hr4775pl.pdf National Association of College and University Attorneys 17 Exhibit Four – Draft Holding Statements Generic Holding Statement in response to Major On-Campus Event [Bomb threat, emergency response, etc.] University officials are actively cooperating with local authorities, including the [POLICE/FIRE/EMERGENCY SERVICES] department(s), to manage the [EVENT/SITUATION]. There is no higher priority for the University than the health and safety of the campus community, and we are taking this situation very seriously. In consultation with the authorities and in accordance with approved University procedures, we have [LIST ACTION(S) TAKEN]: Evacuated a portion of the campus Directed students, faculty and staff to shelter in place [OTHER, AS APPROPRIATE] We will continue to work with the proper authorities to take any additional precautions and response actions that may be appropriate. The University is regularly updating the campus via [LIST OUTREACH MECHANISM(S)] and will also post information on our official website at www.your institution.edu. If you have any additional questions regarding the specifics of the [EVENT/SITUATION], please contact the [POLICE/FIRE/EMERGENCY SERVICES]. National Association of College and University Attorneys 18 Exhibit Four – Draft Holding Statements Generic Holding Statement in response to Moderate On-Campus Event [Fire, blackout, police response, etc.] University officials are cooperating with local authorities to respond to the [EVENT/OCCURRENCE] on campus. Our top priority is the well-being of the campus community, and we are taking appropriate steps in coordination with the [POLICE/FIRE/EMERGENCY SERVICES] department(s). As a result of the [EVENT/OCCURRENCE], we are experiencing some temporary disruptions such as [ROAD CLOSINGS/POWER OUTAGE]. Once the [EVENT/OCCURRENCE] has been appropriately addressed, we will work to restore routine operations as soon as possible. Generic Holding Statement in response to Major Off-Campus Event [Terrorist threat, hurricane, etc.] University officials are working with [POLICE/FIRE/EMERGENCY SERVICES] to assess the [EVENT/SITUATION] and determine if it could affect the campus. The health and safety of the campus community remains our highest priority, and we will work with the authorities to determine the appropriate steps and implement any necessary precautions/preparations. Due to the [EVENT/SITUATION], we are advising students, faculty and staff to [FILL IN]. As the situation continues to develop, we will regularly update the campus via [LIST OUTREACH MECHANISM(S)], and will notify students, faculty and staff about additional actions. National Association of College and University Attorneys 19 Resources NACUA Outlines Bridgham, Bethany. Ethical Issues in Responding to Government Investigation, National Association of College and University Attorneys (NACUA), June 2003. Kehl, Shelley Sanders. Managing Terrorism Risks: A Post-September 11th Evaluation, The Worst-Case Scenario Survival Outline for Colleges. National Association of College and University Attorneys (NACUA), June 2002. Montanaro, Lisa. Campus Security and Crisis Management: Best Practices. Lessons Learned. National Association of College and University Attorneys (NACUA), June 2002. Niehoff, Len. Campus Security and Crisis Management: Best Practices. Some Observations for the College or University Lawyer. National Association of College and University Attorneys (NACUA), June 2002. Additional Sources Anderson, Donald D., Denise Barndt, Jonathan L. Bernstein, Daniel E. Karson, Drew McKay, & Richard Seleznov. “When Disaster Strikes: The Legal Department’s New Imperative.” American Corporate Counsel Association (ACCA), 2001. Gurnick, David & Tal Grinblat. “Be Prepared-Managing Catastrophic Risks in Franchise Systems.” Franchise Law Journal, Winter 2002. Hennelly, Debra Sabatini, Vincent M. Gonzales, and Charles C. Read. “Responding to an Environmental Disaster: The First 48 Hours.” ACCA Docket 21, No. 7 (July/August 2003). Jerry, II, Robert H. “Insurance, Terrorism, and 9/11: Reflections on Three Threshold Questions.” Connecticut Insurance Law Journal, Fall 2002. Kolb, Kim R. and William K. Principe. “OSHA Inspection: How to Prepare.” ACCA Docket 21, No. 8 (September 2003). Kyle, IV, Earle F. and Gerald B. Lefcourt. “Help! I’ve Been Subpoenaed! What Do I Do?” ACCA Docket 20, No. 9 (October 2002). O’Reilly, James T. “Planning for the Unthinkable: Environmental Disaster Planning Issues in An Age of Terroristic Threats.” Widener Law Symposium Journal, 2003. National Association of College and University Attorneys 20 Nicholson, William C. “Legal Issues in Emergency Response to Terrorism Incidents Involving Hazardous Materials: The Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response (“Hazwoper”) Standard, Standard Operating Procedures, Mutual Aid and the Incident Management System.” Widener Law Symposium Journal, 2003. Nortz, James A. “Business Ethics: Put Some Life Into Your Program.” ACC Docket 22, No. 2 (February 2004). Sellier, Bertrand C. and Stacy L. Klein. “Internal Investigations – Safeguarding Privileges.” The Metropolitan Corporate Counsel 12, No. 1 (January 2004). “The Receptionist’s Guide to Front Desk Security.” Padgett-Thompson, 1st Ed., 2001. Tran, Bao Q. and Jonathan P. Tomes. “Risk Analysis: Your Key to Compliance.” ACCA Docket 21, No. 10 (November/December 2003). Villa, John K. “Communications With Your Insurer: Are They Privileged and Protected From Disclosure to Third Parties?” ACC Docket 22, No. 3 (March 2004). Waite, William F. and David S. Claridge. “Terrorism Risk Management Strategies for Businesses.” ACCA Docket 21, No. 8 (September 2003). Whitmore, Ann H., Thomas E. Schick, and Kenneth M. Kastner. “Liability from Hazardous Materials Transportation: Are You Protected?” ACCA Docket 20, No. 10 (November/December 2002). National Association of College and University Attorneys 21