Negotiating the Politics of Gender in Iran

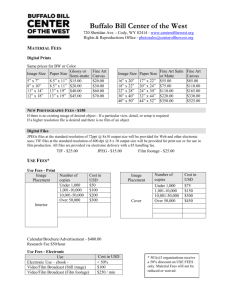

advertisement