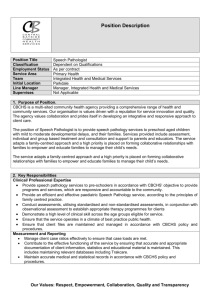

Family-centred, person-centred practice

advertisement