Struggles for Justice

advertisement

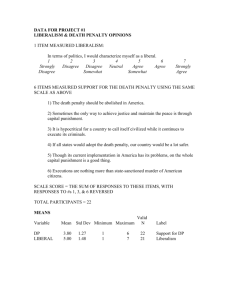

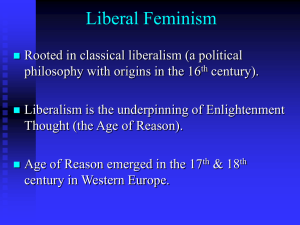

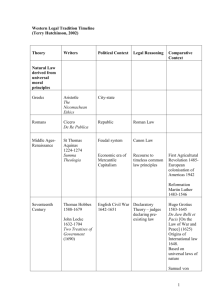

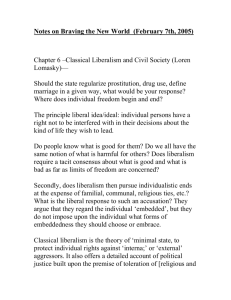

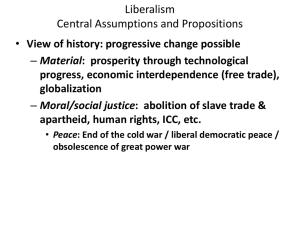

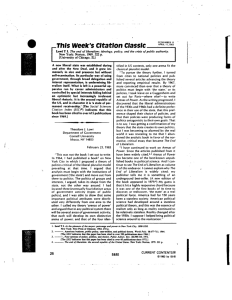

Dawley, Alan. Struggles for Justice: Social Responsibility and the Liberal State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991. In this sweeping panorama of American political and social development between the Gilded Age and the Great Depression, Dawley explores the basic tension that he believes defined America in the modern era: how to reconcile a dynamic society with conceptions of 19th-century liberalism. The old notions of political liberalism such as egalitarianism, self-government, rugged individualism, and protection for the family farm were increasingly distant realities as the nineteenth century faded and the twentieth emerged, yet the ideals of that former liberalism remained—leading to frequent clashes. Those conflicts dealt with differing conceptions of labor, gender roles, and racial and ethnic tensions, and in the midst of all these difficulties loomed the question of the proper role of government. Dawley divides his study into three periods, beginning with the late 1800s and running to the eve of WWI. In the first period, dominated increasingly by big-business interests, laissezfaire liberalism ruled and allowed for tremendous social inequality as corporate powers manipulated American politics and its citizens. Though ethnic, labor, gender, and racial struggles were frequent, their success was limited because economic power and imperialism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and the tremendous nationalism that ensued, helped the government to justify the status quo. Between the period before WWI and 1924 another “type” of liberal state emerged, based on one of two “national elite” strategies to maintain control. Progressive liberalism saw the state finally incorporating some of the reform ideals of the early twentieth century, and was championed especially by Woodrow Wilson, but still favored the wealthy and large capital interests and was not as “progressive” as the stereotype of trust-busting implies. The war, however, destroyed such progressive reform and instead issued in the strategy of managerial liberalism. The state used the corporate model to control mass society, but was unable to continue these emergency measures effectively after the war, so that classic liberalism and the power of big business reemerged, along with a renewed sense of racial and foreign resentment. The imbalances of the early twentieth century were finally solved when the crisis of the Great Depression forced the governing elites to wrestle with their proper role over society. Dawley argues that Roosevelt built upon the managerial liberal ideals of Hoover in constructing the New Deal welfare state that reigned in corporate greed and replaced liberty and equality with “security” as the central feature of American liberalism. He writes, “the New Deal enshrined a new set of ruling values keyed to security, so that the mass of the population . . . felt as if the government cared about their welfare.” (395) As with any work of this scope, there are some key limitations. For example, the title indicates that “justice” and “social responsibility” are the key issues for the liberal state during these decades, yet we never really learn what those things mean. The size of the study also means that neither cultural or intellectual historians will be entirely satisfied—not enough statistics and not enough “real” people! There also is a fairly obvious bias in Dawley’s portrayal of the “heroes” during the decades he covers. Those who get the most favorable coverage are the “radicals”, whether fighting for gender rights, labor rights, racial equality, or a host of other causes. Nonetheless, this is an important work to wrestle with in understanding the relationship of the liberal state to the emerging modern society.