POLS 1000-05 (BNW 6&7)

advertisement

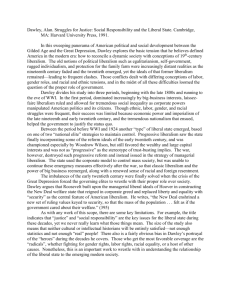

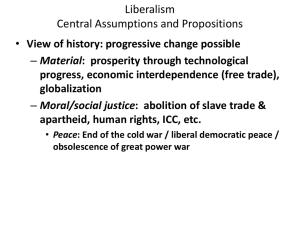

Notes on Braving the New World (February 7th, 2005) Chapter 6 –Classical Liberalism and Civil Society (Loren Lomasky)— Should the state regularize prostitution, drug use, define marriage in a given way, what would be your response? Where does individual freedom begin and end? The principle liberal idea/ideal: individual persons have a right not to be interfered with in their decisions about the kind of life they wish to lead. Do people know what is good for them? Do we all have the same notion of what is harmful for others? Does liberalism require a tacit consensus about what is good and what is bad as far as limits of freedom are concerned? Secondly, does liberalism then pursue individualistic ends at the expense of familial, communal, religious ties, etc.? What is the liberal response to such an accusation? They argue that they regard the individual ‘embedded’, but they do not impose upon the individual what forms of embeddedness they should choose or embrace. Classical liberalism is the theory of ‘minimal state, to protect individual rights against ‘interna;’ or ‘external’ aggressors. It also offers a detailed account of political justice built upon the premise of toleration of [religious and other kinds of] difference. It refrains, at the outset, from the prescription of a specific form of a good life. These ideals can be read as lack of broader concerns for the society and decentralization of questions of choice towards ‘common good’. However, liberalism argues that individuals are the fundamental bearers of moral status and they do not need the community to impose upon them. Liberalism thus believes in only two tenets, liberty, and, our equality to enjoy that liberty. How do we define rights? Life, liberty, and property are the three most traditional cannons of liberalism. These are defined in a negative way as they should NOT be interfered with. Thus, traditional liberalism does not endorse positive rights. Liberal individuals are thus sometimes characterised as ‘minisovereigns’, normatively separated from each other, only coming together if they have an overlapping interest, and prescribing to a minimalistic account of ‘recommended forms of human sociability’. They are social beings, but their sociality should not take away their autonomy. Associations and forms of social behaviour is key to the liberal ideal, but it is secondary importance to the autonomy of the individual. The key line of criticism against liberalism comes in the form of the assertion that there are always power politics in society and we are not starting from a point of equality. Thus, remedial measures need to be taken to bring everyone to the same level to enjoy the liberties purported by liberalism. There is also difference of opinion among liberal theorists about the origin and nature of rights and liberties. Some emphasise natural rights, others privilege the notion of utility, yet others believe in the formation of a liberal community by choice and human effort—known as the social contract theory--. They also do not deny the inherent ‘partiality’ of individuals. Rights, in this sense, provide the individual immunity from imposition upon them larger forms of moral dictates that may limit their choice. Liberalism thus also have serious problems with majoritarianism. They favour voluntaristic associations and forms of negotiation rather than set principles of political conduct. Would it be true that if people are simply left alone, they would live happily ever after? What about the welfare state and its redistributionist policies? What about intervention when states or groups commit crimes against innocent civilians? Critics of liberalism, however, are more worried about the limitation of capitalism and its global mindset than the limitations proposed by the liberals upon the state. Capitalist economics, they argue, robs people of their individuality and of their sense of self-worth and value and liberalism is blind to such concerns. Other critics, mainly of communitarian persuasion, believe that there is something inherently good and solid about communal values that need to be protected and cherished as much as individual rights. This latter discourse is accommodated within liberalism under the heading of ‘group rights’. The remaining question is, is the liberal ethos equally hospitable to both market and non-market oriented conduct and forms of association? Or is it simply an anecdote to capitalist mode of thinking? Chapter 7: Conservatism (Gerald Owen) Are there still conservatives? What separates them from reformers, neoliberals, third-way labour, new social democrats? --belief in the status quo and traditions --adversity towards change --a temperament of caution --emphasis on communal norms and values and their protection --plutocracy --evolution rather than revolution approach to politics --belief in natural law and order --propensity to support nationalism/patriotism --gusto and a strong sense of populist support (they represent the ordinary people although they themselves hardly have ordinary origins) --a mixed regime, favourin protection of past remnants --very limited reliance on state intervention to protect the vulnerable --organic sense of society --emphasis on purity of politics, norms, communities, etc. By and large, it has been and remains as a reactionary ideology and it is flexible and can accommodate other ideologies as a survival strategy. Is it a political persuasion rather than a clear cut ideology?