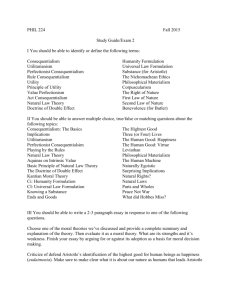

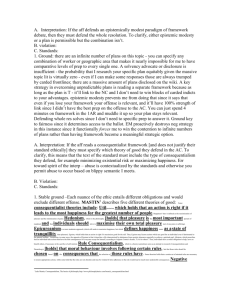

Consequentialism and Supererogation

advertisement