INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ORGANIZATION THEORY AND

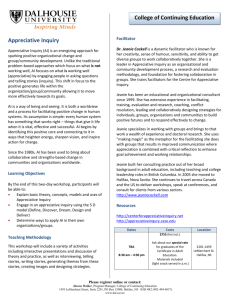

advertisement