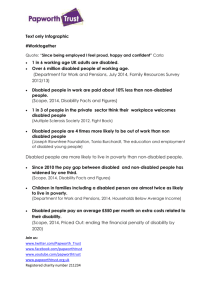

Disabled people`s experiences of accessing goods and services

advertisement