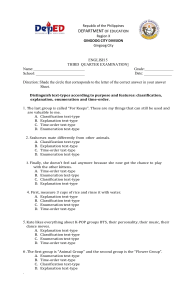

Text typology

advertisement

Text-Typology: Being an integral part of translation theory, text-typology seems to be the most adequate approach to encounter translation loss. It does not regard translation as a sterile linguistic exercise, but as an act of communication, i.e., as a communicative process that takes place within a social context. The distinctive feature of texttypology is its view of a text as an actual representation of a certain text-type, i.e., it can be considered a token of that text-type.It also takes text analysis as a preliminary step to translating. By virtue of text-typology, a number of basic notions will be introduced to translators such as structure, texture, and context. By learning how to take the text to pieces, the translator will be able to reconstruct its context and to relate context to structure and texture. Structure refers to how a text is organized. This kind of organization is hierarchical: a text is composed of paragraphs, paragraphs of sentences, and sentences of smaller units such as clauses , phrases and words. Texture is the way various elements of a text hang together to establish connectivity.According to Halliday and Hasan (1976: 2),20 ‘ A text has texture, and this is what distinguishes it from something that is not a text… the texture is provided by the cohesive relation.’ The cohesive elements present in the text signal to the translator that a certain element in that text is dependent on another, and has to be interpreted in relation to it. Of course, understanding structure and texture is very useful for translators, as it enables them to achieve an objective reading of the source language text. As a result, the translators will be able to preserve the source language text-type by finding the closest equivalence in the target language text, with the least possible modifications to the source language text. Underlying the feasibility of the notions discussed above is the hypothesis which posits that it is the structure of text determined by the context which motivates the deployment of the various devices of texture and, therefore, plays the major role in assigning the text to one of the known text-types. It follows from this that training the translators in different text-types is indispensable in a text-typologically-oriented translating syllabus. The translators must be trained to take any text to pieces referring, in the meantime , to the function of each text segment, in Van Dijk’s own words (1977), ‘ Micro-structure’ and ‘Macro-structure’, within the whole act of communication. This can be made easier by increasing the translator’s awareness of the existence of certain clues within the text which mark text opening, opposition, and conclusion. In generic terms, we can define text-type as any set of texts which share common characteristics in terms of lexis, grammar, structure, and function.According to de Beaugrande and Dressler: ‘ A text-type is a set of heuristics for producing , predicting, and processing textual occurrences and hence acts as a prominent determiner of efficiency, and effectiveness and appropriateness’( 1981: 186).21 Generally speaking, text-types, according to Hatim(1984), can be categorized into three major types: 1. Expository texts: a. Descriptive is used to describe objects and relations in space. b. Narrative is used to narrate events. c. Conceptual is used to analyse and sythesize concepts. 2. Argumentative texts: They are used to evaluate events, entities or concepts with the aim of making a case or putting forward a point of view and, consequently, to influence future behaviour. Argumentative texts can be subclassified into: a. Overt argumentation: an example of this could be the counterargumentative ‘letter to the editor’. b. Covert argumentation: an example of this can be the implicit argument in an editorial or what is called ‘ the thesis cited to be opposed’ or the case-making propaganda tract. 3. Instructional texts: They aim at planning and directing future behaviour of the addressees. This kind of texts is subdivided into: a. Instruction with option as in advertising. b. Instruction without option as in treaties, contracts, and legal documents. Armed with the criteria of text-typology, we, as translators, do realize that this approach is the most adequate among others for many reasons. In the first place, text-typology helps translators to identify text-type which is an essential step in the process of translation. It follows, then, that how to translate is primarily a function of the text to be translated. Admittedly, the identification of a text preserves the source language text-type.In other words, it preserves both the spirit and vividness of the message in the target language text. On such a basis, translation loss is considerably minimized. Moreover, texttypology enables the translator to deal with text as a maximal unit,i.e.,to take into consideration three major textual elements: context ( pragmatics, semiotics, and communicativeness), structure and texture. In so doing, the translator can be said to have achieved a functional equivalence. In this context, in order to establish functional equivalence, the translator may need to alter the structure of the text so that it will conform to the target language text norms. Thus, it will meet one of the requirements of translation, ‘appropriateness’, one of the seven standards of ‘textuality’ according to de Beaugrande and Dressler (1981). Viewed from this perspective, text-typology pays attention to contextual meaning in text interpretation and highlights the importance of the contextual variables in the deployment of the elements of structure and texture.